The Salpêtrière Hospital: The 19th Century Parisian Asylum That Shaped Modern Medicine and Misunderstood Women

- Oct 30, 2025

- 7 min read

Paris in the 19th century was a city of contradictions: dazzling and dark, progressive and cruel. Beneath the shimmering gaslights and grand boulevards, there existed another world, the world of the Salpêtrière Hospital.

This vast institution on the Rue de la Santé began life as an arsenal and saltpetre factory (hence its name), before being transformed in the 17th century into a hospice for poor and destitute women. By the 19th century, however, it had become something stranger and more complex, part hospital, part asylum, part prison, and part stage.

Within its walls were housed thousands of women: the elderly, the mentally ill, epileptics, prostitutes, and those deemed “deviant.” It was a city within a city, a closed world of suffering and study that mirrored society’s deepest anxieties about gender, morality, and madness.

From Arsenal to Asylum

The Salpêtrière’s story begins in 1656, when King Louis XIV, guided by his minister Jean-Baptiste Colbert, decreed the creation of the Hôpital Général de Paris, a vast social experiment meant to contain the poor, sick, and “unruly.” The Salpêtrière was reserved for women.

By the time the 19th century arrived, it had grown to house around 5,000 residents, making it one of the largest hospitals in Europe. It was divided into sections: the “old women’s quarter,” the “epileptics,” the “criminals,” and the “madwomen.”

The line between charity and punishment was thin. Women were often sent there not for crimes but for simply stepping outside the boundaries of what society considered acceptable female behaviour. A wife accused of hysteria, a girl deemed too “wayward,” or a mother who had turned to prostitution could find herself locked within its towering gates.

The conditions were grim. Historian Lisa Appignanesi, in her book Mad, Bad and Sad, wrote, “The Salpêtrière was as much a warehouse of women as it was a hospital, a human archive of social failure.”

The Birth of Neurology

And yet, from this grim setting, a revolution in medical science emerged.

In 1862, a man named Jean-Martin Charcot became chief physician of the Salpêtrière. Charcot was a brilliant neurologist, sometimes described as “the Napoleon of the neuroses.” Under his direction, the hospital became the world’s leading centre for the study of the brain and nervous disorders.

Charcot’s interest lay especially in hysteria, a condition then believed to affect only women, marked by convulsions, paralysis, and emotional outbursts. For centuries, hysteria had been linked to the womb (from the Greek hystera), seen as a sign of feminine weakness or moral failing.

Charcot rejected the old superstitions. He believed hysteria was a real neurological disorder, not witchcraft or madness. He began to classify its symptoms and study them scientifically, or so he thought.

His Tuesday lectures at the Salpêtrière became legendary. The public and medical elite flocked to watch his patients, women in white gowns, fall into trances, cry, faint, or contort their bodies under hypnosis. Charcot would narrate, pointer in hand, as though conducting a symphony of suffering.

The Theatre of Hysteria

To modern eyes, Charcot’s demonstrations seem unsettling, even theatrical. And indeed, that was part of their appeal. Artists, writers, and intellectuals from all over Paris attended these lectures. Among them was a young Sigmund Freud, who translated Charcot’s work into German and later developed his own theories of psychoanalysis from what he witnessed there.

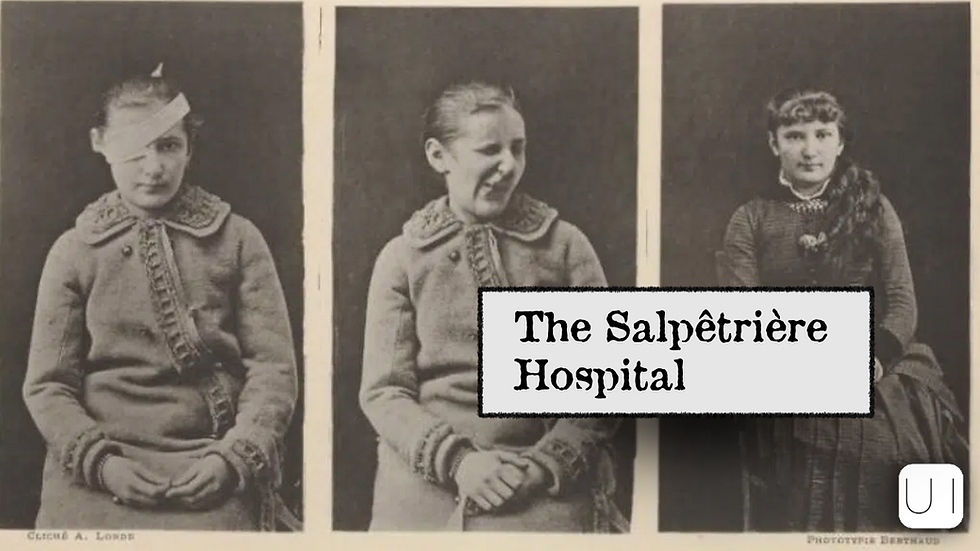

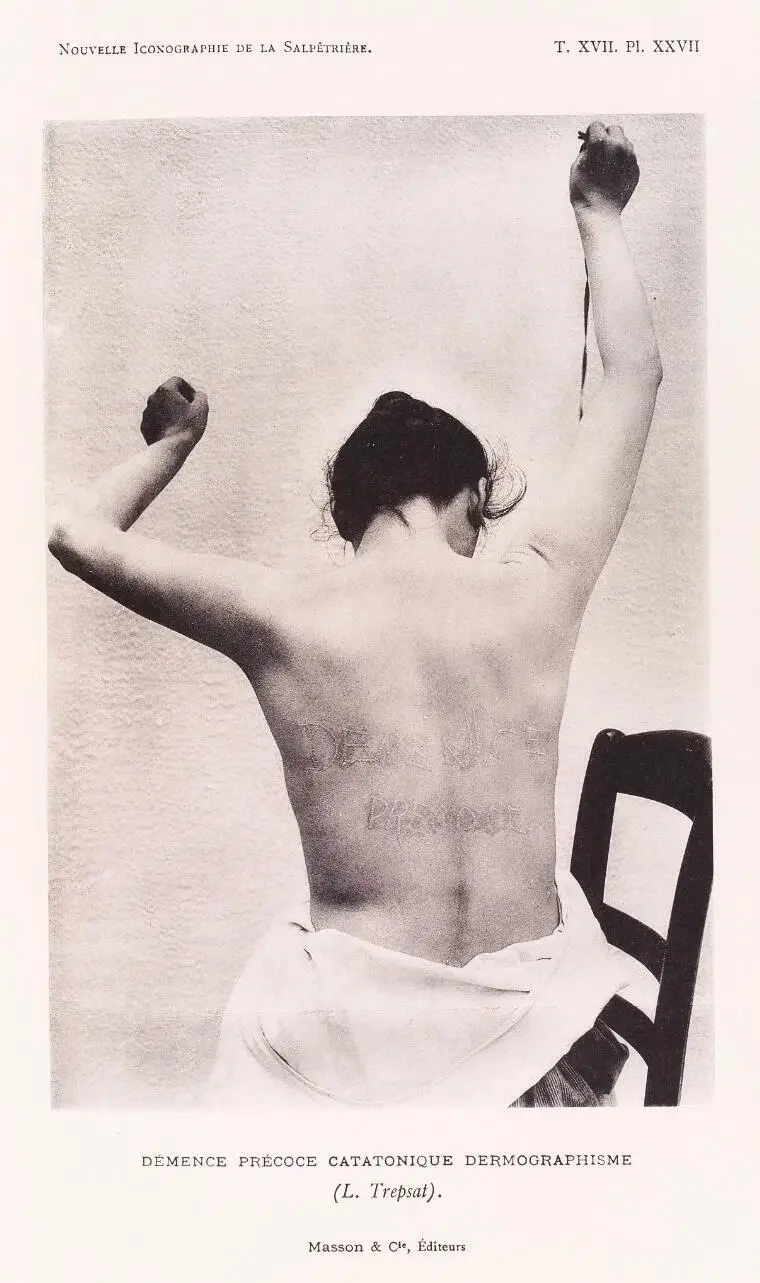

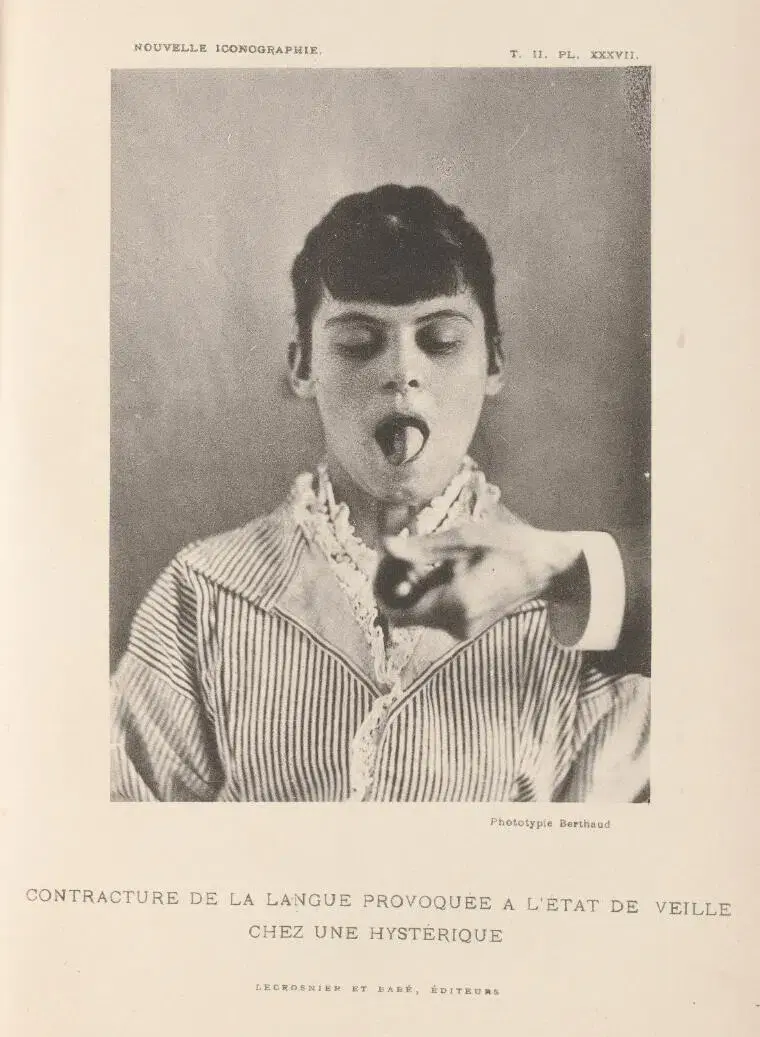

Photographers, too, captured the spectacle. The hospital’s photographic service, led by Albert Londe, produced hundreds of striking images of patients mid-attack, their faces twisted in agony or ecstasy. These photographs, published in Iconographie Photographique de la Salpêtrière, are both scientific documents and haunting works of art.

Charcot’s most famous patient, Augustine, became the icon of this era. Admitted at age fifteen after fleeing an abusive home, Augustine suffered convulsions, paralysis, and hallucinations. Charcot and his assistants photographed her repeatedly, her body becoming an anatomical canvas onto which male doctors projected their theories.

In one image she appears wide-eyed and arched in what was called the attitude passionnelle, the “ecstatic pose.” In another, she faints gracefully backward, like a saint in a painting. These images circulated widely, reinforcing the connection between femininity and hysteria in the public imagination.

A Place of Contradiction and Control

For the women who lived there, the Salpêtrière could be both prison and sanctuary. Some were grateful for food and safety after years of poverty. Others longed for freedom, their days governed by strict routines, surveillance, and endless medical scrutiny.

There were endless layers of control: physical, moral, and psychological. The patients were subjected to experiments with electricity, hypnosis, and ice baths. They were examined and categorised, “the hysteric,” “the epileptic,” “the melancholic.” Their individuality was often lost amid the case files.

And yet, within this rigid system, small acts of rebellion and resilience occurred. Augustine, the star hysteric, once attempted to escape disguised as a man. Other women expressed themselves through art or religion, or formed quiet alliances with fellow inmates.

The Influence Beyond the Hospital Walls

The Salpêtrière’s reach extended far beyond its gates. Its influence on both medicine and culture was immense.

In art, the “hysterical woman” became a recurring motif. Painters like André Brouillet immortalised Charcot’s lectures, while writers such as Émile Zola and Joris-Karl Huysmans used the hospital as inspiration for their depictions of psychological breakdown and female suffering.

In science, the Salpêtrière laid the groundwork for neurology and psychiatry. Charcot’s research on multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, and aphasia was groundbreaking. His students, including Freud, Babinski, and Gilles de la Tourette, went on to found entire branches of modern medicine.

But the hospital’s legacy is also deeply gendered. The hysteria diagnosis, though couched in science, reflected Victorian society’s fears about women’s autonomy. The boundaries between mental illness and moral judgement were dangerously blurred.

As feminist scholar Elaine Showalter later observed, “The hysterical woman was not so much cured as silenced.”

The Women of the Salpêtrière

While male doctors built reputations on their “discoveries,” the women who inspired them were largely forgotten. Yet they left traces, in letters, testimonies, and those haunting photographs.

Take Geneviève, who was institutionalised for “melancholy” after the death of her child. Or Blanche Wittmann, another of Charcot’s famous patients, whose seizures became textbook examples. After Charcot’s death, Blanche worked with Marie Curie in a laboratory, her arms scarred by radiation. She later told friends she preferred the burns to the electric shocks of the Salpêtrière.

Their stories remind us that behind every medical breakthrough is a human life, often one sacrificed to the name of progress.

From Asylum to Modern Hospital

By the early 20th century, the Salpêtrière began to change. Psychiatry was evolving, and the old language of hysteria was falling out of favour. After Charcot’s death in 1893, his school fragmented. His successor, Joseph Babinski, moved away from hypnotic spectacle toward more empirical neurology.

In 1907, the asylum was renamed Hôpital de la Salpêtrière, signalling a shift from incarceration to treatment. Gradually, it integrated into Paris’s public hospital network and became one of the most respected neurological institutions in Europe, known today as Hôpital Pitié-Salpêtrière, part of the Assistance Publique – Hôpitaux de Paris (AP-HP).

Today, the site where women once screamed and fainted before an audience is a place of quiet clinical professionalism. Few visitors realise that within those elegant courtyards, history’s most famous “madwomen” once lived and died.

Legacy and Reappraisal

In recent decades, artists, historians, and feminists have returned to the story of the Salpêtrière to ask uncomfortable questions.

Was Charcot a visionary or a showman? Were his patients victims or collaborators in the creation of a new kind of medical narrative? And what does it mean that so many women’s pain was aestheticised, turned into spectacle and symbol?

Contemporary writers such as Asti Hustvedt (Medical Muses: Hysteria in Nineteenth-Century Paris) and Georges Didi-Huberman (Invention of Hysteria) have re-examined the archive, offering more compassionate readings of the women once dismissed as “mad.” Their work reveals not only how hysteria shaped modern psychiatry but also how it reflected deep social and gender hierarchies.

The Salpêtrière, they argue, was a mirror of its age, one that showed both the birth of medical modernity and the persistence of ancient fears about female emotion, sexuality, and intellect.

The Salpêtrière in Popular Imagination

The hospital’s ghost still haunts popular culture.

Artists continue to reference its imagery, from photographers who reinterpret Londe’s “hysterical poses” to filmmakers who explore its atmosphere of beauty and terror. Fashion designer Alexander McQueen famously drew inspiration from the Iconographie Photographique de la Salpêtrière, reimagining the women’s contorted gestures in his 1999 collections.

Even the language of hysteria persists in everyday speech, long after the diagnosis itself was removed from psychiatric manuals. The word remains a cultural echo of those Parisian wards where medicine, performance, and prejudice once collided.

A Place of Pain and Progress

To walk through the modern Salpêtrière today is to walk over centuries of history, past elegant pavilions and tree-lined paths that once echoed with cries and prayers. The iron gates remain, but what lies behind them has transformed.

Here, once, thousands of forgotten women were confined in the name of morality and science. Here, modern neurology was born. And here, the idea of the “hysterical woman,” part patient, part myth, took shape and spread across the world.

It is a story of progress built on paradox: compassion mingled with control, curiosity with cruelty.

Charcot himself once said, “Theory is good, but it doesn’t prevent things from existing.” The women of the Salpêtrière existed. Their suffering was real, even when misunderstood.

Today, remembering them helps us reflect on how far we have come, and how easily we might repeat old mistakes when we turn human lives into data, diagnosis, or display.

Sources

Hustvedt, Asti. Medical Muses: Hysteria in Nineteenth-Century Paris. Bloomsbury, 2011.

Didi-Huberman, Georges. Invention of Hysteria: Charcot and the Photographic Iconography of the Salpêtrière. MIT Press, 2003.

Appignanesi, Lisa. Mad, Bad and Sad. Virago, 2008.

Micale, Mark. Approaching Hysteria: Disease and Its Interpretations. Princeton University Press, 1995.

Andrews, Jonathan. “The Salpêtrière and the Performance of Madness.” History of Psychiatry, Vol. 17, No. 4 (2006).

Showalter, Elaine. The Female Malady: Women, Madness, and English Culture, 1830–1980. Virago, 1987.

Didi-Huberman, Georges. L’Invention de l’hystérie: Charcot et l’iconographie photographique de la Salpêtrière. Macula, 1982.

Zola, Émile. Le Docteur Pascal. Paris, 1893.

Comments