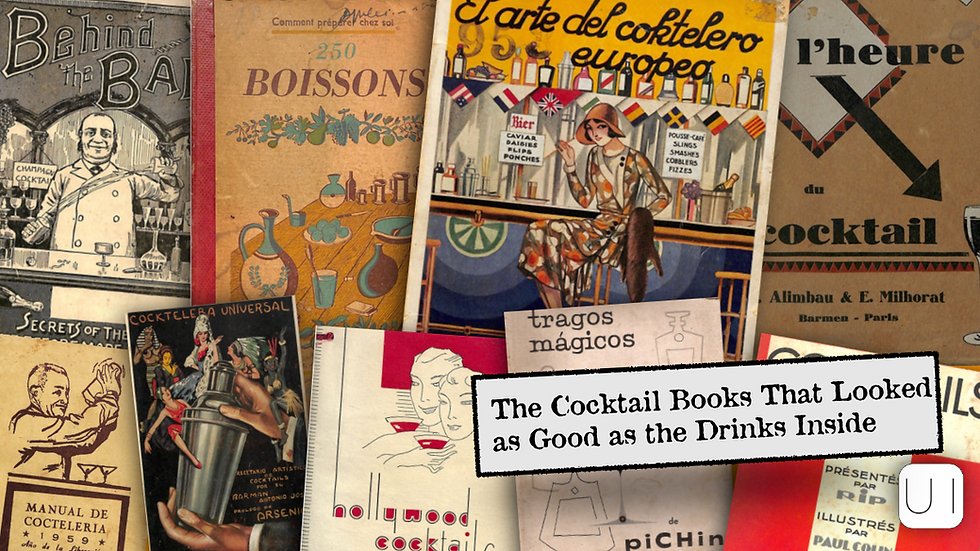

The Cocktail Books That Looked as Good as the Drinks Inside

- Jan 11

- 4 min read

Where do the cocktail obsessives of Tokyo, Mexico City and Brooklyn really get their ideas from. Behind the reclaimed wood bars, bespoke ice programmes and aggressively seasonal garnishes, there is a strong chance the answer lies somewhere far less fashionable and far more paper based.

If not directly from the Exposition Universelle des Vins et Spiritueux, then at least from the same deep well of inherited barroom folklore. The EUVS, an initiative of the Museum of Wine and Spirits on the sun baked Île de Bendor off the coast of southeastern France, has quietly digitised a treasure trove of vintage cocktail books. It is a gloriously unfiltered record of how people once drank, talked about drinking, and justified it to themselves and others.

This is not just a collection for bartenders. It is catnip for anyone interested in design, illustration, advertising language, and the shifting social rules that once governed who drank what, when, and why. Long before tasting menus and concept bars, cocktails were already doing cultural heavy lifting.

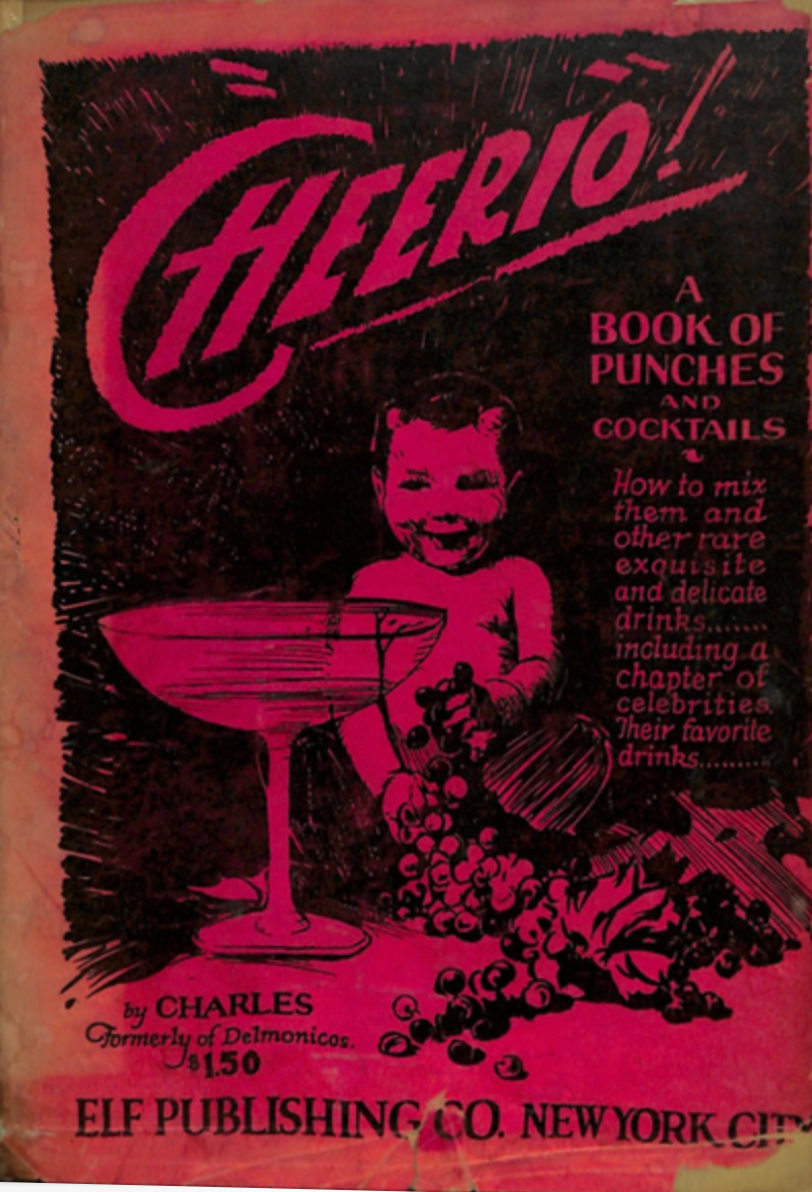

Take Cheerio, a Book of Punches and Cocktails from 1928. Its author, known only as Charles, is introduced with the sort of grand understatement that now feels like parody. He is described as “one who has served drinks to Princes, Magnates and Senators of many nations.” The absence of a surname feels less like modesty and more like professional survival instinct. Charles had previously worked at Delmonico’s, a name that carried serious weight in American dining at the time.

Charles was clearly a man who believed the cocktail should be present at every stage of human consciousness. His book arranges drinks according to the hour, beginning with the bleak early morning moment when one “staggers out of bed, groggy, grouchy and cross tempered.” His suggested remedies include the Charleston Bracer and the Brandy Port Nog, both of which read less like drinks and more like medical interventions.

As the day wears on, the tone darkens. By midnight, the cocktails are pitched as emotional support. Insomnia, bad dreams, disillusionment and despair, he warns, require sterner measures. This is where the Cholera Cocktail and the Egg Whiskey Fizz make their entrance. One senses that Charles had seen some things.

The book also contains a section devoted to celebrity favourites. The names themselves have largely slipped into obscurity, but the first person anecdotes restore them with surprising clarity. Vaudeville star Trixie Friganza, writing about a drink discovered in Venice, recalls:

“In that nautical city of Venice, I first made the acquaintance of a remarkably delicious drink known as ‘Port and Starboard’.”

She then carefully explains the layered construction of grenadine and crème de menthe, before trailing off into a nostalgic sigh. “Dear old Venice.” It is a small moment, but it captures how cocktails functioned as souvenirs long before fridge magnets and Instagram.

The collection is also refreshingly honest about Prohibition. Rather than pretending it was not happening, many books acknowledge it directly. Cheerio includes a section on Temperance Drinks, alcohol free concoctions that require minimal effort and even less enthusiasm. There is no Shirley Temple in sight. The child star was barely toddling when the book was published. Instead, readers are offered a Saratoga Cooler or an Oggle Noggle, both of which sound faintly judgmental.

Fast forward to 1949 and Bottoms Up: A Guide to Pleasant Drinking. The book opens with a poem so aggressively whimsical that it almost dares the reader to drink before attempting to read it aloud. Sober, it barely scans. After a couple of Depth Bomb Cocktails or a Merry Widow Cocktail No. 1, it probably still does not scan, but at least you will not care.

By this point, cocktail books had become barely disguised advertisements. Many of the recipes are solid enough, but they are framed by cheerful endorsements and slogans. One sponsor promised speed and efficiency with the line “for Liquor… Quicker,” which feels like the sort of phrase that could still be found neon lit above a bar today.

The swinging sixties bring a shift in tone rather than substance. Eddie Clark’s Shaking in the 60’s arrives with confidence. Clark had serious credentials, having served as head bartender at the Savoy Hotel, the Berkeley Hotel and the Albany Club. He dedicates the book to “all imbibing lovers,” a phrase that manages to be both inclusive and faintly alarming.

Clark’s earlier titles included Shaking with Eddie, Shake Again with Eddie and Practical Bar Management from 1954. There is a sense of a man who knows his niche and intends to occupy it fully. His recipes are straightforward, occasionally eccentric, and very fond of Pernod. Drinks such as the Beatnik, the Bunny Hug and the Monkey Hugall reflect a moment when naming a cocktail after a subculture felt daring.

The illustrations, by William S. McCall, lean heavily into anthropomorphism. Elephants drink with gusto. Cocktail glasses sprout limbs. Women appear with improbable proportions and minimal clothing. Even allowing for the era, some of it has not aged gracefully. Still, the images are part of the record. They tell us what was considered playful, glamorous, or acceptable decoration in a drinks manual intended for the average home.

Clark also takes his teaching role seriously. He includes sections on measurement conversions, bar supplies, and how to propose a toast without embarrassing yourself. Most revealing is the inclusion of a party log, a structured record of who attended, what was served, and presumably what went wrong. It feels like the analogue ancestor of a group chat that everyone quietly regrets the next morning.

Perhaps the most telling detail is Clark’s quiet confidence. He genuinely believes his book can help readers host unforgettable evenings. For those waking up the following day, he recommends the Morning Mashie, another Pernod based concoction dedicated to “all those entering the hangover class.” It is hard not to admire the honesty.

Taken together, the EUVS collection reads like a long running conversation between generations of drinkers. The tools have changed, the glassware has improved, and the ice is undeniably better, but the underlying impulses remain familiar. The desire to mark time, to soften the edges of the day, to turn memory into something pourable.

So when a bartender in Brooklyn reaches for a forgotten liqueur, or someone in Tokyo resurrects a layered drink with surgical precision, they are not inventing as much as continuing a tradition. The past is already there, digitised, slightly stained, and waiting to be shaken again.

Comments