Homer Sykes And The Ordinary Britain He Paid Attention To

- Jan 26

- 6 min read

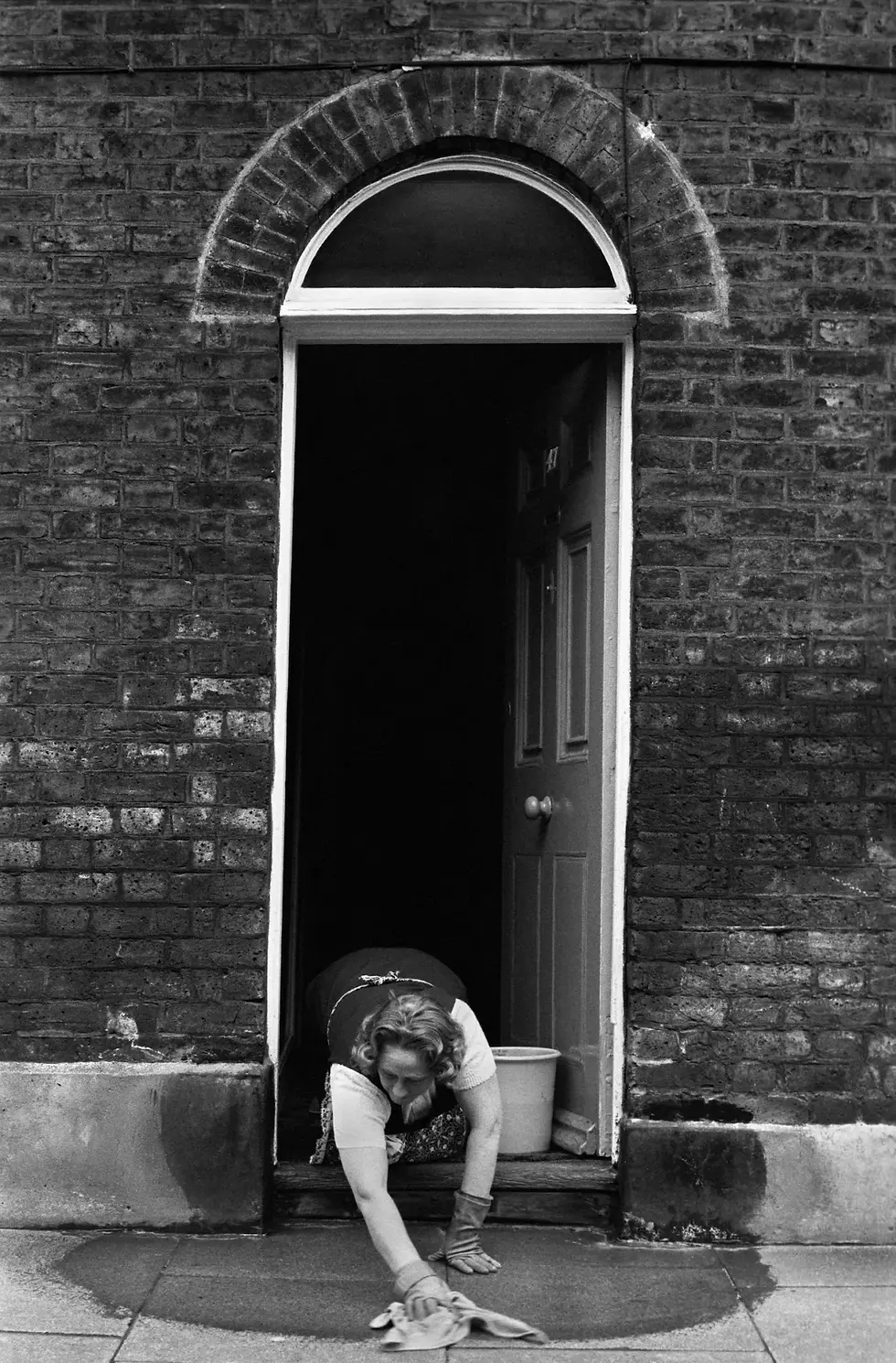

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Homer Sykes could often be found standing quietly at the edge of a gathering. A wedding outside a registry office. A village fête on a slightly windswept green. Guests arriving early, unsure where to stand, waiting for something to happen. These were not headline moments, and that was exactly why they interested him.

Sykes’ early career, later brought together in The Way We Were: 1968 to 1983, grew out of a simple impulse: to photograph everyday British life as it actually looked at the time. There was no sense that he was documenting anything especially important. He was just paying attention.

Finding subjects close to home

Homer Sykes was born in 1949 and began photographing seriously while still very young. Britain already had plenty of photographers working in fashion, advertising, and newspapers, but far fewer were spending long periods looking at ordinary social situations. Sykes found himself drawn to those gaps.

Rather than travel far or seek out dramatic subject matter, he worked close to home. Weddings became a regular focus, partly because they were easy to access and partly because they revealed a lot about how people wanted to be seen. Church halls, council buildings, suburban streets, seaside towns. These settings formed the background to his early work.

At the time, Sykes did not see this as social history. He has since said that he simply felt these scenes were worth recording before they disappeared or changed beyond recognition.

Britain in the 1970s, without comment

The years covered by 1968 to 1983 sit in an interesting space. Much of British life still followed long established patterns, but those patterns were starting to loosen. Industry was declining. Communities were changing. Television was shaping tastes and expectations, even as local rituals carried on much as they always had.

Sykes’ photographs show this without making a point of it. People stand awkwardly at weddings. Guests smoke outside reception venues. Children linger at the edges of adult conversations. Nothing is exaggerated, and nothing is smoothed over.

What makes the work effective is its lack of judgement. Sykes does not mock his subjects, but he does not sentimentalise them either. He lets details accumulate naturally.

Weddings as familiar ground

Weddings appear frequently in Sykes’ early photographs. They offered a ready made structure and a cross section of people who might not otherwise appear together. Family members, neighbours, colleagues, and friends all gathered in one place, dressed for the occasion, aware of being observed.

Unlike traditional wedding photography, Sykes focused less on the ceremony and more on the spaces around it. People waiting. Guests looking slightly uncomfortable. The moment just before or just after the formal photograph.

These images feel recognisable to anyone who attended weddings in Britain during that period. The clothing, the postures, the expressions all speak to a shared social experience.

A low key way of working

Technically, Sykes’ approach was straightforward. He worked in black and white, used available light, and avoided anything that drew attention to the camera. This allowed him to blend in and wait for moments to unfold rather than forcing them.

He has described himself more as an observer than a director. People were not asked to pose or perform. The photographs rely on timing rather than intervention.

This low key approach is one reason the work still feels approachable. The images do not feel constructed. They feel noticed.

When everyday scenes become records

By the time The Way We Were was published, many of the customs Sykes photographed were already beginning to fade. Weddings became more informal. Community events declined. Public behaviour shifted.

As a result, photographs that once seemed unremarkable began to carry more weight. Not because they depicted famous events, but because they showed how people once gathered and behaved in public.

Sykes has often pointed out that many of the people he photographed would never have thought of themselves as part of a historical record. That was never the intention. They were simply going about their lives.

Influence without noise

Sykes’ early work has since been widely referenced in discussions of British documentary photography. It offered an alternative to more dramatic or stylised approaches, showing that careful observation could be enough.

You can see its influence in later photographers who focus on routine, community, and social habits without turning them into spectacle. The lesson was simple: you do not need to exaggerate everyday life to make it interesting.

Looking at it now

Viewed today, The Way We Were: 1968 to 1983 feels less like a statement and more like a quiet archive. The value lies in the accumulation of small moments rather than any single image.

For readers interested in social history, Sykes’ early photographs offer a clear view of how Britain looked and behaved before many familiar structures changed. It is not a romantic portrait, and it is not a critique. It is simply a careful record of people, places, and habits that once felt entirely normal.

Comments