Lovers’ Eyes: The Secret Miniature Portraits of Georgian Romance

- Daniel Holland

- 20 minutes ago

- 5 min read

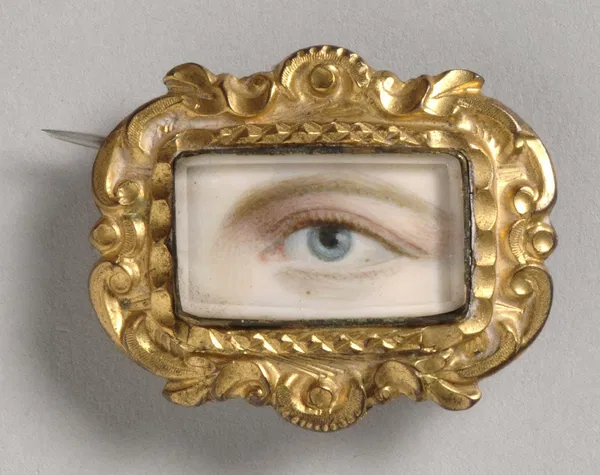

There are moments in the history of art when a fashion appears so precise, so emotionally loaded, that it seems to belong entirely to its own private world. Lovers’ eye miniatures sit firmly in that category. Small enough to be hidden in the palm of a hand, painted with almost obsessive care, and intended for a single recipient, these fragments of gaze tell a story not of public display but of secrecy, intimacy, and coded affection in late eighteenth and early nineteenth century Britain.

At first glance, a painted eye set into a ring or locket can feel faintly unsettling. Detached from the face, it appears to hover between romance and oddity. Yet for the people who commissioned, gifted, and wore them, lovers’ eyes were deeply meaningful objects. They were not curiosities. They were declarations of attachment in a society where love was often constrained by class, religion, and reputation.

Miniature Portraits and the Culture of Intimacy

By the 1770s, miniature portraits were everywhere in polite British society. Painted in watercolour on thin slices of ivory, they offered a portable alternative to large oil paintings and could be commissioned relatively quickly. Officers carried them on campaign, families exchanged them as keepsakes, and lovers wore them close to the body.

Ivory was prized for its soft translucence, which gave skin tones a lifelike glow. But it was also unforgiving. A single drop of water could ruin hours of work. Miniaturists developed extraordinary control, rendering eyelashes, reflections of light, and subtle changes in colour on a surface only a few centimetres across. These were not casual objects. They were technical achievements as well as emotional ones.

Within this already specialised genre emerged an even narrower fashion: portraits that showed only one eye, cropped so tightly that nothing else of the face remained. These images were later labelled “lovers’ eyes”, a name that stuck because it captured their purpose so precisely.

What a Lover’s Eye Meant

Despite appearances, a lover’s eye did not signal watchfulness or possession. It was not a visual equivalent of “I have my eye on you”. Its meaning was more vulnerable. The message was closer to “you have my heart, and here is my eye to prove it”.

An isolated eye could only be identified by someone who already knew the face it belonged to. To everyone else, it was anonymous. That anonymity was part of the appeal. These miniatures allowed intimacy without exposure, recognition without public declaration.

They were set into rings, brooches, lockets, toothpick cases, and snuff boxes. Often they were hidden rather than displayed, turned inward against the body or concealed beneath clothing. They were handled more often than they were shown, their surfaces warmed by touch. Like folded letters carried in a pocket, their power lay in proximity.

Secrecy, Desire, and Coded Romance

One explanation sometimes offered for the rise of eye miniatures is artistic boredom, the idea that painters, weary of repeating similar commissions, experimented by isolating a single feature. While artists undoubtedly enjoyed the technical challenge, this does not fully explain why clients embraced the form so enthusiastically.

A more convincing explanation lies in erotic whimsy and social necessity. Eighteenth century Britain was rich in coded forms of communication. Fans, gloves, flowers, and even the way one held a handkerchief carried agreed meanings. Lovers’ eyes fitted neatly into this culture of signals.

For couples whose relationships needed to remain discreet, an eye miniature was ideal. It could be worn openly without revealing anything to outsiders. Even for couples whose attachments were socially acceptable, there was pleasure in the secrecy itself. The eye was a fragment, and fragments invite imagination.

Royal Origins of the Fashion

The lovers’ eye fashion in England is most often traced to a royal romance. The future George IV, then Prince of Wales, fell deeply in love with Maria Fitzherbert, a woman entirely unsuitable to his position. She was a Roman Catholic, barred by law from marrying the heir to the throne, and a widowed commoner.

Their relationship was conducted in secrecy and shadowed by political pressure. During their courtship, George sent Maria a miniature painting of his eye along with a covert proposal of marriage. The gesture was accepted, and the two married privately, though the union had no legal standing.

Their relationship endured for years despite financial strain, public scandal, and George’s repeated infidelities. When he died in the early nineteenth century, he was buried with a miniature of Maria’s eye. What began as a coded declaration became a lifelong emblem of attachment.

Once the royal connection became known, the fashion spread quickly among the aristocracy and aspiring middle classes. To own or exchange a lover’s eye was to participate in a language of intimacy that had royal precedent.

The Problem of the Disembodied Eye

To modern eyes, quite literally, the idea of wearing a painted eye can provoke discomfort. An eye pinned to a dress does not gaze lovingly at its owner. It stares outward, indifferent and fixed. There is also a faint suggestion of the anatomical, even the monstrous, in wearing a fragment of a body.

These objections are logical, but they miss how sentimental objects function. Lovers’ eyes were not meant to withstand analytical scrutiny. Like many practices associated with romance, their meaning collapses if examined too closely. What mattered was not what the object did in public, but what it represented in private.

The eye did not need to look back at the lover. Its presence was enough. It stood in for a shared history, a recognised face, and a mutual understanding that did not require explanation.

A Revealing Comparison: Beauty Revealed

The logic of lovers’ eyes becomes clearer when placed alongside another miniature from the same period that takes intimacy much further. In the late 1820s, the American artist Sarah Goodridge, one of the most celebrated miniaturists of her day, painted a tiny self portrait showing her bare breasts. The work, titled Beauty Revealed, was executed with the same technical delicacy as any lover’s eye.

Goodridge gave the miniature to her lover, the statesman Daniel Webster. Their relationship was emotionally intense and deeply private. Webster was married to another woman, and Goodridge never married. The miniature was kept among Webster’s most personal possessions.

Beauty Revealed is often treated as an anomaly, but it exposes the shared structure underlying these objects. Both the eye and the breasts are fragments. Both assume a viewer who already knows the rest. Both rely on recognition rather than explanation.

Goodridge’s gift simply removes the coyness. Where a lover’s eye suggests remembrance, her miniature declares presence. Here I am. Do not forget me. In this light, the eye appears restrained rather than strange.

The Decline of the Lover’s Eye

The fashion for lovers’ eyes faded by the middle of the nineteenth century. Several factors contributed to its decline. Changes in taste favoured larger, more explicit forms of portraiture. The use of ivory became increasingly controversial and impractical. Most significantly, photography transformed how people recorded likeness and memory.

Photography offered speed, accuracy, and accessibility. It removed much of the mystery that had made fragmentary portraits appealing. A full face could now be captured quickly and cheaply. The coded language of the eye lost its necessity.

Yet the surviving miniatures retain their power. Many are unsigned. Their sitters remain unknown. What survives is the gaze itself, suspended without context but still charged with intention.

Why Lovers’ Eyes Still Matter

Today, lovers’ eyes sit in museum cases and auction catalogues, often treated as charming oddities. But they are more than decorative curios. They are evidence of how people navigated emotional life within rigid social structures.

They remind us that intimacy does not always seek visibility. In an era dominated by public declarations and instant images, the lovers’ eye offers a different model of romantic expression. It is quiet, partial, and deliberately obscure.

In that obscurity lies its enduring appeal. A fragment can sometimes say more than a whole.