The Brixton Riots of 1981 and the Tensions That Led to a National Reckoning

- Daniel Holland

- 26 minutes ago

- 9 min read

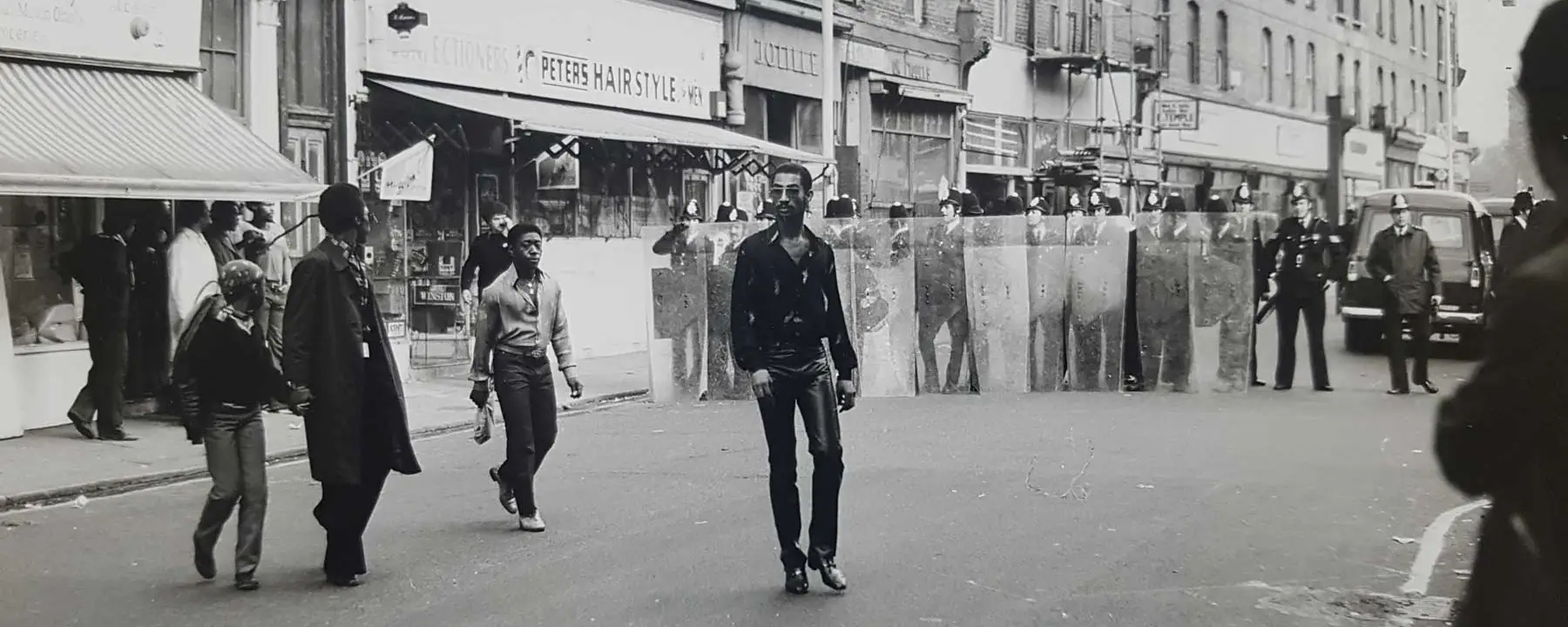

On the afternoon of 10th April, 1981, a small crowd gathered on Railton Road in Brixton as police attempted to assist a badly injured teenager. Within forty eight hours, that moment had escalated into one of the most significant episodes of civil unrest in modern British history. Over three days, large parts of Brixton were set alight, hundreds were injured, and the relationship between Britain’s Black communities and the police was laid bare in full public view.

The Brixton riots were not a sudden eruption of chaos, nor were they the product of a single incident. They were the outcome of long standing social, economic and political pressures that had been building for decades in a part of London already struggling with deprivation, unemployment and deep rooted mistrust of authority.

From Windrush to Brixton

To understand why Brixton became the epicentre of such intense unrest in 1981, it is necessary to look further back. After the Second World War, Britain actively recruited labour from its colonies to rebuild the economy. One of the most symbolic moments in this post war migration was the arrival of the Empire Windrush at Tilbury on 22nd June, 1948, carrying hundreds of Caribbean migrants. Many settled in south London, and over the following decades Brixton developed into a centre of Black British life.

By the 1960s and 1970s, Brixton was known for its music, food, political activism and strong community networks. At the same time, Black residents faced routine discrimination in housing, employment and public services. Landlords often refused to rent to Black families, and job applicants were regularly turned away because of their race. These everyday exclusions shaped a collective experience of marginalisation that never disappeared.

By the late 1970s, Brixton was vibrant but economically fragile. The national recession that deepened in the early 1980s hit working class communities hard, and it hit Brixton harder still.

Economic Decline and Social Strain

By 1981, unemployment in Brixton stood at around 13 per cent overall. Among ethnic minorities, it was closer to 25 per cent, and for young Black men estimates ran as high as 55 per cent. Housing conditions were poor, with many families living in overcrowded or decaying properties. Public investment had declined, and youth services were limited.

Crime rates were rising, particularly robbery and violent theft. In 1980 alone, more than 30,000 crimes were recorded in the London Borough of Lambeth, with a large proportion taking place in the Brixton division. For the police, this created pressure to act. For the community, it deepened the sense that Brixton was being treated as a problem area rather than a neighbourhood worthy of long term support.

Policing, Stop and Search and the Sus Law

Relations between the local African Caribbean community and the Metropolitan Police had been deteriorating for years. Many Black residents believed they were being treated as suspects simply for existing in public space. The widespread use of stop and search powers reinforced that belief.

At the centre of this was the Sus law, a power derived from the Vagrancy Act of 1824. It allowed police to stop and arrest individuals on suspicion alone, without evidence that a crime had been committed. In practice, it was used disproportionately against young Black men. Being stopped multiple times in a single day was not unusual for some residents.

Adding to this sense of harassment was the involvement of the Special Patrol Group. This elite unit, designed to respond to public order situations, had already built a reputation for aggressive tactics and heavy handed policing. Its deployment to Brixton in early April 1981 was widely interpreted as a show of force rather than an attempt at community reassurance.

The New Cross Fire and a Crisis of Trust

Tensions were further inflamed by events earlier in the year. On 18th January, 1981, thirteen Black teenagers and young adults died in a fire during a house party in New Cross, a nearby area of south east London. Although authorities stated that the fire was accidental and had started inside the building, many in the community believed it had been a racist arson attack.

The police investigation was widely criticised as slow and dismissive. For many Black Londoners, it confirmed a long held belief that their lives were not valued equally by the state.

In response, Black activists including Darcus Howe organised the Black People’s Day of Action on 02nd March, 1981. Thousands marched from Deptford to Hyde Park in a powerful demonstration of grief and anger. While most of the march passed without serious incident, there were clashes with police at Blackfriars. National newspapers focused heavily on confrontations and framed the event through racial stereotypes, while much of the local press reported the march more respectfully.

A few weeks later, some of the march organisers were arrested and charged with riot, though they were later acquitted. The episode further damaged trust between the community and the authorities.

Operation Swamp 81

Against this already charged backdrop, the Metropolitan Police launched Operation Swamp 81 at the beginning of April. The operation was intended to reduce street crime in Brixton, where robbery and violent theft were rising. Officers from other districts and members of the Special Patrol Group were drafted in. Plain clothed officers flooded the area, and uniformed patrols were increased.

Within five days, 943 people were stopped and searched, and 82 were arrested. The vast majority of those stopped were young Black men. To many residents, the operation felt less like crime prevention and more like a military occupation.

The name itself carried an uncomfortable political echo. It referenced Margaret Thatcher’s 1978 remark that Britain might be “swamped by people with a different culture”. For those on the receiving end of the stop and search campaign, the symbolism was not lost.

The Immediate Spark: 10th April, 1981

The incident that finally tipped Brixton into open conflict took place at around 5.15 pm on Friday 10th April. A police constable spotted a Black teenager, Michael Bailey, running down the street. He had been stabbed and was bleeding heavily. After briefly escaping, Bailey was stopped again on Atlantic Road, where officers realised he had a four inch wound.

Bailey ran into a nearby flat, where a family and the officer tried to stem the bleeding with kitchen roll. As police attempted to take him to a minicab on Railton Road to get him to hospital, a crowd gathered. Many in the crowd believed the police were not helping him quickly enough or were treating him as a suspect rather than a victim.

When a police car arrived and stopped the minicab, officers moved Bailey into the back of the police vehicle to take him to hospital more rapidly. A group of youths, thinking he was being arrested, began shouting for his release. One voice was heard to shout, “Look, they’re killing him.” The crowd surged forward and pulled Bailey from the car.

Rumours spread rapidly that the police had left a wounded Black youth to die, or had harassed him instead of helping him. In reality, Bailey survived his injuries, but that fact did not become widely known until later. By the evening, more than 200 young people, Black and white, had gathered and begun confronting officers.

Rather than scaling back their presence, the police increased foot patrols in Railton Road and continued Operation Swamp 81 throughout the night. The decision only deepened resentment.

Railton Road and the Front Line

Railton Road, where the first clashes occurred, was not just another street. Known locally as the Front Line, it was the social heart of Black Brixton. It was lined with clubs, record shops, cafés and informal meeting places. It was a space where people gathered, exchanged news and built community.

The fact that the most intense violence and destruction took place there gave the riots a deeper symbolic weight. For many residents, it felt as though the centre of their community life was under direct assault.

Bloody Saturday: 11th April, 1981

By the morning of Saturday 11th April, the situation was primed to explode. Many in the community incorrectly believed that Michael Bailey had died as a result of police brutality. Crowds gathered throughout the day, and tensions rose steadily.

At around 4 pm, two police officers stopped and searched a minicab in Railton Road. By this point, Brixton Road, also known as Brixton High Street, was filled with angry people. Police cars were pelted with bricks, and confrontations spread quickly.

The violence escalated sharply from around 5 pm. Shops were looted on Railton Road, Mayall Road, Leeson Road, Acre Lane and Brixton Road. The first major fire was reported at 6.15 pm when a police van was set alight on Railton Road. Firefighters attempting to reach the scene were attacked with stones and bottles by crowds at the junction of Railton Road and Shakespeare Road.

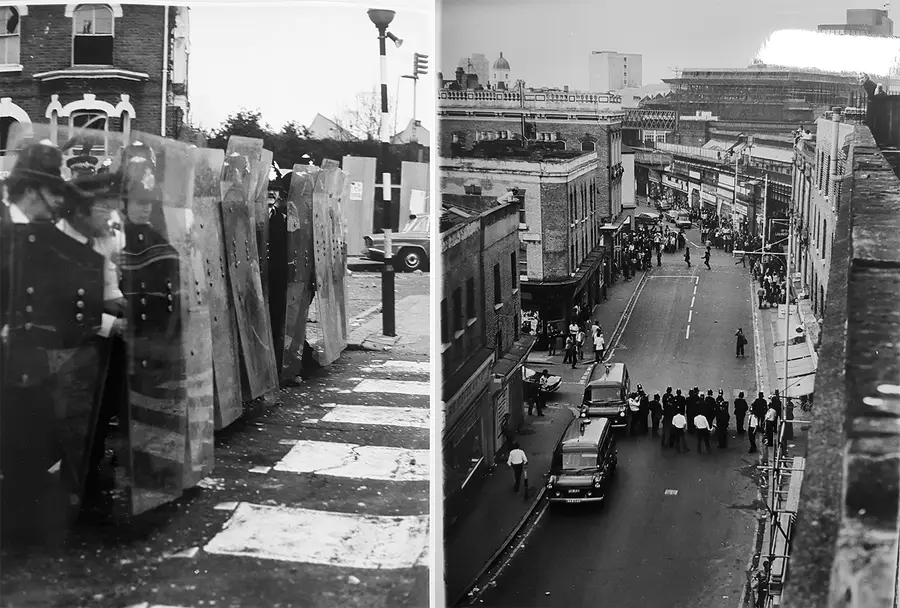

The police, unprepared for the scale of unrest, struggled to respond. Many officers had only basic protective equipment, including plastic shields that were not fireproof. Communication systems broke down, and there was no clear strategy for containing the disorder.

Officers formed shield walls and attempted to push crowds out of key areas. Rioters threw bricks, bottles and petrol bombs. Some local residents who were not involved in the violence tried to mediate, urging both sides to step back and de escalate. Their efforts failed.

By around 8 pm, the destruction reached its peak. Two pubs, twenty six businesses, schools and other buildings were set alight. Time magazine later dubbed the day Bloody Saturday.

By 9.30 pm, more than 1,000 police officers had been sent to Brixton. By 1 am on 12th April, the area was largely under control, and by the early hours of Sunday morning, the rioting had faded.

The Human and Physical Cost

The toll of the three days of unrest was severe. A total of 299 police officers were injured, along with at least 65 members of the public. Sixty one private vehicles and 56 police vehicles were destroyed. Twenty eight premises were burned down, and another 117 were damaged and looted. Eighty two people were arrested. Estimates suggested that up to 5,000 people may have been involved at various points.

The events in Brixton did not remain isolated. Over the summer of 1981, similar disturbances broke out in other cities and towns, including Handsworth in Birmingham, Toxteth in Liverpool, Moss Side in Manchester, Southall in London and Hyson Green in Nottingham. All of these areas were suffering from high unemployment and deep social inequality, and many had significant Black or minority communities with long standing grievances against the police.

The Scarman Report and Police Reform

In the aftermath of the Brixton riots, Home Secretary William Whitelaw commissioned a public inquiry led by Lord Scarman. The Scarman Report was published on 25th November, 1981.

Scarman concluded that the disturbances were an “outburst of anger and resentment” directed primarily at the police. He found clear evidence of the disproportionate and indiscriminate use of stop and search powers against Black people. He acknowledged that complex political, social and economic factors had created a disposition towards violent protest.

The report recommended changes to policing practices and called for action to tackle racial disadvantage and inner city decline. One of its outcomes was the introduction of a new code of police behaviour under the Police and Criminal Evidence Act of 1984. The Act also created the independent Police Complaints Authority in 1985, intended to help restore public confidence in policing.

Inside the police force itself, senior officers quietly acknowledged that their public order training, equipment and intelligence gathering had been wholly inadequate. Even before Scarman’s recommendations were implemented, internal reforms were already underway, including better riot gear, improved radio communications and the development of more formalised public order units.

Despite these changes, many of Scarman’s broader social recommendations were never fully implemented.

Political Reactions and Continuing Unrest

Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher dismissed the idea that unemployment and racism were central causes of the riots, stating on 13th April, 1981, that “Nothing, but nothing, justifies what happened.” She rejected calls for increased investment in inner cities, arguing that “Money cannot buy either trust or racial harmony.”

Lambeth Council leader Ted Knight described the police presence in Brixton as “an army of occupation”, a remark Thatcher publicly condemned as “absolute nonsense”.

Small scale disturbances continued throughout the summer. After four nights of rioting in Liverpool’s Toxteth area beginning on 04th July, 150 buildings were burned and 781 police officers were injured. CS gas was used on the British mainland for the first time to control the unrest. Brixton itself saw further rioting on 10th July.

Legacy and Later Inquiries

The issues raised by the Brixton riots did not disappear with time. Rioting broke out again in Brixton on 06th October, 1985, and in 1995, each time reflecting unresolved tensions around policing, race and deprivation.

In 1999, the Macpherson Report into the murder of Stephen Lawrence and the failure of the police investigation delivered a damning verdict. It concluded that the Metropolitan Police was “institutionally racist” and argued that the recommendations of the Scarman Report had largely been ignored. Although it did not directly re examine the Brixton riots, it reinforced the idea that the problems exposed in 1981 had never been fully addressed.

A Turning Point in British History

The Brixton riots of April 1981 remain a defining moment in modern British history. They exposed the consequences of systemic racism, economic neglect and aggressive policing tactics in a way that could no longer be ignored. While they led to some reforms, they also left a legacy of unfinished business that continues to shape debates about race, policing and social justice in the United Kingdom.

More than four decades later, the events of those three days in Brixton still resonate, not as a random outbreak of disorder, but as the visible breaking point of a community that had been under pressure for far too long.