The Tattooist Who Documented St Pauli: Herbert Hoffmann’s Hidden Hamburg Archive

- Jan 24

- 6 min read

On any given evening in Hamburg’s St Pauli district in the years after the Second World War, the streets carried a particular rhythm. The clatter of boots on cobbles mixed with music drifting from basement bars. Dockworkers moved between shifts and cheap meals. Sailors, newly paid, clustered around doorways, deciding where to drink or sleep. The neighbourhood existed in a state of near-permanent transition, shaped by arrivals and departures rather than permanence.

In a small room not far from the docks, a man worked quietly, rarely drawing attention to himself. His name was Herbert Hoffmann, and over the course of several decades he would create one of the most important visual records of European tattoo culture ever assembled. Hoffmann was not driven by artistic ambition or historical intent. He was a tattooist, earning a living in a district that existed largely beyond the gaze of respectable society. His photographs emerged from routine, trust, and repetition.

What makes Hoffmann’s work enduring is not spectacle, but intimacy. He documented people who were already accustomed to being overlooked, and he did so without judgement or drama. His archive captures St Pauli not as myth or vice, but as a working environment where bodies bore the marks of labour, migration, memory, and time.

Growing up in a harbour city

Herbert Hoffmann was born in Hamburg in 1919, at a time when the city was still reckoning with the consequences of the First World War and Germany’s shifting political landscape. Hamburg’s harbour was central to its identity, both economically and culturally. The port connected the city to the wider world, bringing foreign goods, languages, and customs into daily life.

For working-class families, the harbour represented employment but also instability. Work was seasonal, physically demanding, and often dangerous. Injuries were common. Bodies aged quickly. It was within this environment that tattooing found a natural place, functioning as both decoration and record keeping. A tattoo could mark a completed voyage, a lost shipmate, a romantic attachment, or simply endurance.

Hoffmann trained as a lithographer, a trade rooted in precision and repetition. Lithography was concerned with line, pressure, and consistency, qualities that would later define his tattooing style. Unlike many tattooists of the era, Hoffmann approached the craft methodically. He was not flamboyant. He did not cultivate an image of rebellion. His professionalism would become a defining feature of his reputation.

War, captivity, and return

The Second World War interrupted Hoffmann’s early adulthood, as it did for an entire generation. He served in the German military and was captured by British forces. Like many former prisoners of war, Hoffmann spoke little about this period later in life. What can be inferred, however, is the impact of confinement, displacement, and enforced proximity to others from varied backgrounds.

When Hoffmann returned to Hamburg after the war, the city was physically scarred and socially fragmented. Entire districts had been destroyed by Allied bombing. Housing shortages were acute. The formal economy struggled to absorb returning soldiers and displaced civilians. Informal trades and cash-in-hand work became essential to survival.

St Pauli, already accustomed to operating outside official structures, adapted quickly.

St Pauli after 1945

To understand Hoffmann’s work, it is essential to understand St Pauli itself. Located close to Hamburg’s docks, the district had long functioned as a liminal space. It was tolerated rather than celebrated, regulated yet never fully controlled. Sailors, sex workers, musicians, petty criminals, and casual labourers lived alongside one another in boarding houses and cramped flats.

After the war, St Pauli became a hub for black-market activity. Cigarettes, alcohol, and rationed goods changed hands openly. Bars operated long hours. Music venues flourished. American and British servicemen introduced new cultural influences, including jazz, fashion, and attitudes toward leisure.

Tattooing thrived in this environment because it met a real need. For sailors and dockworkers, tattoos functioned as identifiers in a transient world. They created continuity in lives defined by movement. Hoffmann’s studio offered not just a service, but a stable point of return.

Becoming a tattooist in postwar Germany

Hoffmann began tattooing professionally in the late 1940s. Tattooing at this time was not regulated in any formal sense. Equipment was often homemade. Machines were adapted from electric motors. Ink quality varied widely, and hygiene standards depended largely on the practitioner’s own discipline.

Hoffmann developed a reputation for care. Clients trusted him not only with their skin, but with their stories. Tattooing sessions often lasted hours, during which conversation flowed naturally. Hoffmann listened more than he spoke. Over time, his studio became a space where people felt seen rather than judged.

Unlike later tattoo culture, there was little emphasis on originality or authorship. Many designs were copied from flash sheets or remembered from previous tattoos seen elsewhere. Hoffmann did not attempt to impose a personal style. His role was to execute the client’s wishes as accurately as possible.

The beginnings of a photographic archive

Hoffmann began photographing his clients in the early 1950s. The motivation was practical. He wanted records of completed tattoos and visual references for future work. Photography was a tool, not a creative outlet.

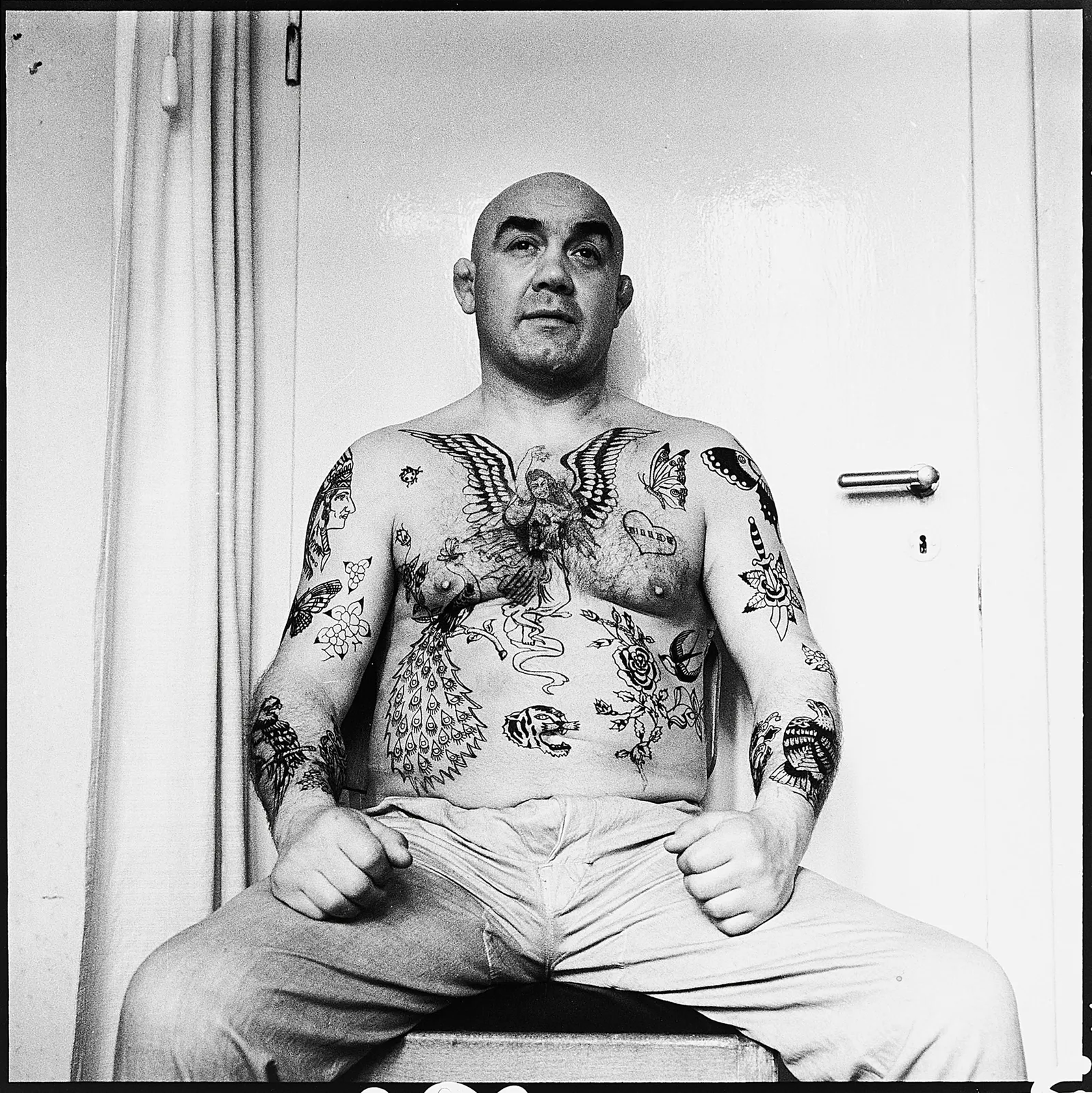

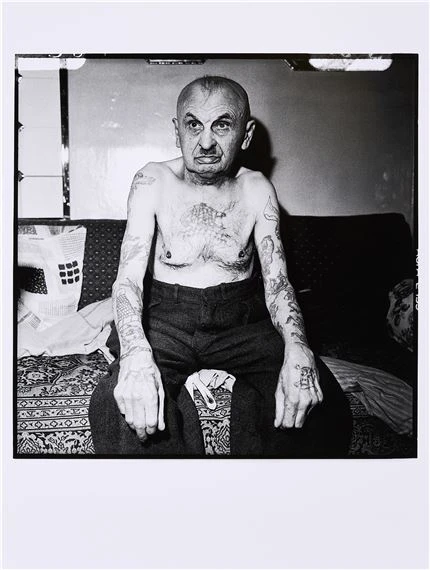

The photographs were taken simply. Hoffmann used plain backgrounds and available light. Subjects stood or sat facing the camera, often shirtless, sometimes awkward, sometimes at ease. There was no attempt to stylise the images. Faces were always visible. Tattoos were shown as part of the body, not isolated fragments.

This decision proved crucial. By including faces, Hoffmann resisted the abstraction of tattooed bodies. Each image insists on the individuality of the person depicted.

Tattooed bodies as social documents

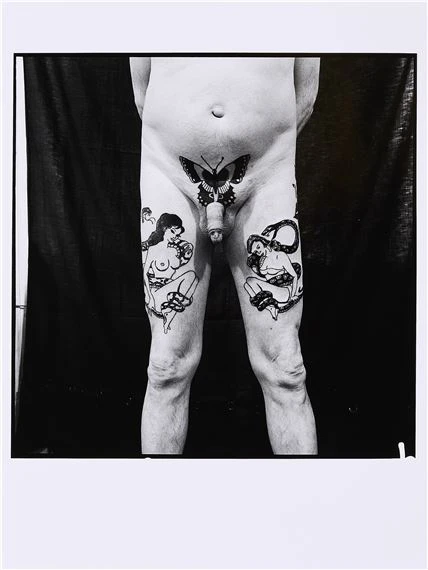

The people Hoffmann photographed came from across St Pauli’s social spectrum. Sailors dominate the archive, but they are not alone. Dockworkers, carnival performers, sex workers, and unemployed men appear frequently. Women are present too, often bearing tattoos acquired earlier in life or during relationships that no longer existed.

The tattoos themselves reflect this diversity. Nautical imagery appears alongside religious symbols, patriotic motifs, erotic scenes, and personal inscriptions. Many tattoos are uneven, faded, or poorly executed by modern standards. Hoffmann did not conceal this. Accuracy mattered more than idealisation.

Importantly, Hoffmann recorded names when possible. This act of naming resists anonymity. It acknowledges that these were not types or categories, but individuals with lives beyond the frame.

Ageing, labour, and time

One of the most striking aspects of Hoffmann’s archive is its attention to ageing. Tattoos age as bodies age. Ink spreads. Lines blur. Skin sags. Hoffmann photographed these changes without sentimentality.

This focus reflects the realities of working-class life in St Pauli. Labour was physical and relentless. Many clients bore scars from accidents or illness. Tattoos coexisted with these marks, forming layered records of survival.

By documenting ageing bodies, Hoffmann challenged emerging notions of tattooing as purely aesthetic. His photographs insist that tattoos are lived objects, inseparable from time and experience.

Ethics and trust

Hoffmann’s photographs feel ethical because they are rooted in long-term relationships. He knew his subjects. He had spent hours in close physical contact with them, building trust. Photography was an extension of this relationship, not an intrusion.

Subjects agreed to be photographed. Hoffmann rarely photographed people outside his studio. This boundary mattered. It prevented exploitation and reinforced consent.

As a result, the images avoid voyeurism. They do not invite the viewer to stare at difference, but to recognise continuity between the lives depicted and broader social history.

Rediscovery and recognition

For many years, Hoffmann’s archive remained largely unknown. Tattooing itself did not gain wider cultural legitimacy in Germany until the late twentieth century. As tattoos became increasingly visible among younger generations, interest in earlier traditions grew.

Exhibitions of Hoffmann’s photographs began appearing in the 1980s and 1990s, often framed as social history rather than art. Hoffmann resisted being labelled an artist, describing himself instead as a craftsman who kept records.

Publication followed, bringing the archive to international attention. Tattooists, historians, and anthropologists recognised its significance. Hoffmann’s work provided rare visual evidence of European tattoo culture outside the dominant American narrative.

Influence and legacy

Today, Hoffmann’s archive is widely cited in studies of tattoo history, working-class culture, and visual anthropology. Contemporary tattooists often reference his work not for stylistic inspiration, but for its ethos.

Hoffmann demonstrated that tattooing is inseparable from social context. His photographs remind us that tattoos were once primarily about memory, labour, and belonging rather than self-branding or fashion.

In an era of curated online identities, his images offer a quieter truth.

Why Herbert Hoffmann still matters

Herbert Hoffmann did not set out to document history. He simply worked, day after day, in a small room near Hamburg’s docks. He tattooed bodies and occasionally photographed them. The power of his archive lies in this ordinariness.

His work asks to be looked at slowly. It offers no spectacle, no mythmaking, only people as they were, marked by their lives.

That restraint is precisely why it endures.