From the Military Cross to the Camera Lens: The Life and Work of John Everard

- Daniel Holland

- 40 minutes ago

- 5 min read

John Everard didn't set out to change photography, start debates, or shock polite society. But for more than three decades, from the late 1920s into the early 1960s, he photographed the human body in a small London studio all the while laws tightened and relaxed, tastes shifted, and fashions came and went, Everard stayed remarkably steady. His photographs were deliberately unsensational. In Britain, that mattered.

Born Edward Ralph Forward, John Everard came to photography later than most. Before he ever opened a studio or published a book, he had already lived a full adult life. He served in the First World War and was awarded the Military Cross, marking him out as an officer who had shown courage and composure under fire. He rarely spoke publicly about his wartime experiences, but the habits they fostered discipline, patience, and emotional restraint would quietly shape everything that followed.

After demobilisation, Everard did not immediately return to Britain’s cultural world. Instead, he worked as a rubber planter overseas, part of the British colonial economy. Plantation life was structured and demanding, far removed from London’s artistic circles. It required long hours, careful organisation, and a tolerance for isolation. When Everard eventually returned to England and turned seriously to photography, he did so as someone already accustomed to control and routine.

By the time he opened his studio in London, Everard was not a young man chasing novelty or recognition. He was someone who understood how to endure, how to work steadily, and how to operate within limits. Those qualities would prove essential for sustaining a long career photographing the nude in a country that was often uneasy, and sometimes openly hostile, towards the genre.

Becoming John Everard

At some point during his transition into photography, Edward Ralph Forward adopted the professional name John Everard. This was a practical decision. Nude photography in Britain occupied a legally awkward space, and many photographers used pseudonyms to separate their work from their private lives. Everard never presented this name change as an artistic statement. It was simply a way of keeping things tidy.

He opened a studio in Orange Street, London, close to Leicester Square. The location placed him near theatres, publishers, and performers, all of whom needed photographs. Everard was entirely self taught. He learned through trial and error, studying classical sculpture and painting for guidance rather than following photographic trends.

His early work covered portraiture, fashion, stage photography, and general studio commissions. Actors and dancers were natural subjects, comfortable holding poses and working under lights. Even in these early images, Everard’s preferences were clear. He liked neutral backgrounds, careful lighting, and poses that emphasised shape rather than personality.

Turning towards the nude

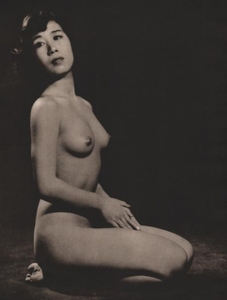

By the late 1920s, Everard increasingly focused on photographing the nude. This was not an unusual interest at the time, but his approach was notably restrained. There were no elaborate sets, no storytelling scenes, and no overt attempts to provoke. The body was treated as form, not spectacle.

Everard often cropped faces or turned them away from the camera, directing attention to posture, balance, and proportion. Lighting was soft and controlled, avoiding dramatic shadows or theatrical effects. The influence of classical statuary is clear throughout his work.

From the late 1920s until the early 1960s, Everard produced nude studies steadily. While Britain’s censorship laws shifted and moral attitudes hardened and softened, his work stayed within narrow boundaries. This consistency allowed him to keep working when others were shut down or forced to operate discreetly.

Books rather than exhibitions

Unlike many photographers, Everard was not interested in galleries or photographic salons. He rarely exhibited publicly and did not pursue institutional recognition. Instead, he focused on publishing books.

This suited both his temperament and the cultural climate. Books could be viewed privately, away from public scrutiny. They also allowed Everard to control sequencing and context. Images were not meant to stand alone but to be seen as part of a series.

One of his best known publications, Second Sitting, included photographs of a young Pamela Green, taken before she became widely known. In Everard’s photographs, Green appears as a study in posture and form rather than glamour. The images are calm and understated, offering a glimpse of her early career before her public image was fully formed.

Another important publication, Eves without Leaves, emerged from a collaboration rather than a solo effort.

Cooperation instead of competition

By 1939, Everard found himself competing with other British nude photographers, notably Walter Bird and Horace Roye. Rather than continuing to fight over a limited market, the three men made a practical decision. They agreed to cooperate.

Together they formed Photo Centre Ltd, establishing their headquarters in rooms above Walter Bird’s studio in Savile Row. This was not an artistic collective so much as a survival strategy. By pooling resources, sharing printing costs, and coordinating publications, they made it easier to operate within Britain’s restrictive environment.

Each photographer maintained his own style. Horace Roye leaned more openly towards glamour, Bird maintained strong ties to theatre and society portraiture, and Everard remained the most formally restrained. The partnership allowed these differences to coexist.

Working methods and studio discipline

Everard’s studio sessions were formal and controlled. Models were expected to hold poses for extended periods, with changes introduced slowly and deliberately. This was not a space for improvisation. His approach reflected a belief that refinement came through repetition rather than spontaneity.

Models were usually paid per session rather than per image, encouraging long sittings and careful variation. This structure directly shaped the rhythm of his work. Small shifts in posture or lighting created a series rather than a single defining image.

Notably, Everard’s studio was free from scandal. In an era when nude photography often attracted suspicion, his reputation for professionalism mattered. It helped him maintain working relationships with publishers and printers who were wary of legal trouble.

War, austerity, and censorship

The Second World War disrupted Everard’s output but did not end it. Paper shortages, blackout regulations, and increased moral scrutiny reduced opportunities for publication. Everard responded by slowing production rather than changing direction.

His status as a decorated war veteran likely helped insulate him socially, even if it did not exempt him from censorship laws. After the war, as Britain moved through austerity and gradual liberalisation, Everard resumed publishing with little stylistic change.

By the early 1960s, however, photography was moving on. New generations embraced location shooting, spontaneity, and a more overtly sexualised aesthetic. Everard’s careful studio studies began to look old fashioned. He gradually withdrew from active production.

A long legacy

John Everard never became a household name. He did not seek attention, court controversy, or position himself as a rebel. Instead, he built a long career by understanding limits and working within them.

Today, his photographs survive in private collections, specialist libraries, and archives. They are valued not for shock or novelty, but for what they reveal about how nude photography functioned in Britain under constraint. His work shows how a photographer could keep working through war, censorship, and social change simply by being careful, consistent, and patient.

Everard’s career is a reminder that much of photographic history is made quietly. Not through grand gestures, but through persistence.