The Explosive Rat and Britain’s Most Ingenious WW2 Sabotage Devices

- Daniel Holland

- 1 hour ago

- 7 min read

In the early years of the Second World War, while the Luftwaffe bombed British cities and German troops occupied much of Europe, a very different kind of battle was being planned behind locked doors in Britain. It involved no armies and very few guns. Instead, it revolved around everyday objects that could be picked up, thrown away, burned, or casually handled without a second thought. Among them was one of the strangest weapons ever devised by a modern state: a dead rat, quietly packed with explosive.

The story of the explosive rat sits at the centre of a much wider culture of ingenuity that defined Britain’s wartime sabotage effort. It was conceived by the Special Operations Executive, a secret organisation set up in 1940 at the direct urging of Winston Churchill, who famously ordered it to “set Europe ablaze”. The SOE was tasked with training agents, supplying resistance movements, and developing methods of sabotage that could disrupt the German war machine far behind enemy lines.

To do that, the organisation built a parallel world of invention. In laboratories hidden in the British countryside, scientists, engineers, craftsmen, and former criminals worked side by side, designing devices that disguised explosives inside the ordinary clutter of civilian life. Some of these ideas were clever. Others were bizarre. A few, like the explosive rat, were so unsettling that their psychological effect turned out to be more powerful than their physical one.

The workshop of secret war

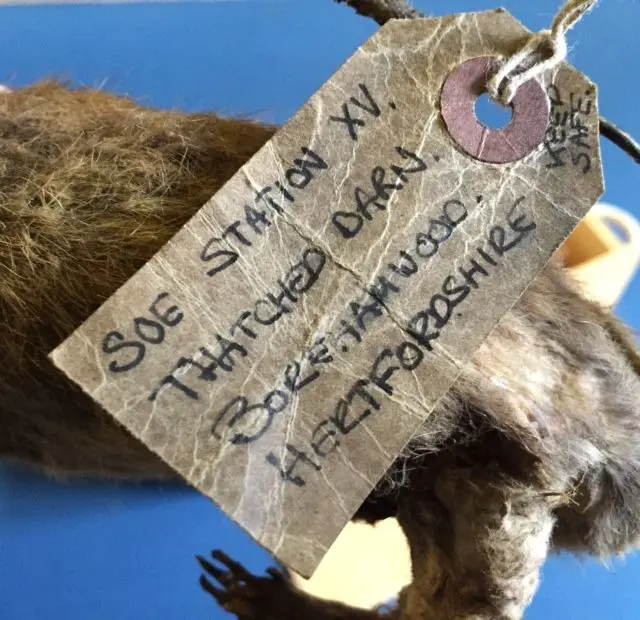

Much of the SOE’s technical work took place at Station IX, based at Aston House in Stevenage, Hertfordshire. Here, under conditions of extreme secrecy, a team of specialists produced a catalogue of devices that reads today like something from fiction. Explosives were hidden inside soap bars, bottles of Chianti, lumps of coal, bicycle pumps, books, tins of food, and even plaster logs. Wireless sets were concealed inside bundles of firewood. Codes were written on silk and hidden in collar studs, toothpaste tubes, matchboxes, and sponges.

The guiding principle was simple. Sabotage would work best when it looked like accident, carelessness, or bad luck. A derailed train should appear to be the result of mechanical failure. A boiler explosion should look like industrial negligence. The fewer obvious signs of enemy action, the better.

To achieve this, SOE designers paid obsessive attention to detail. Section Q, the unit responsible for equipment development, studied continental fashions so that buttons were sewn in the correct style for different regions. Footwear was designed to leave misleading tracks. For operations in Asia, agents were issued sandals with soles that imprinted Japanese or local footprints, ensuring that anyone following their trail would assume they were native.

This attention to camouflage extended beyond appearance to behaviour. SOE files reveal that crude psychoanalysis was applied to agent training, including oddly frank discussions of fear, sexuality, and talkativeness under stress. One internal report even suggested that some agents struggled to destroy cipher pads because the act symbolised castration at an unconscious level. It was an organisation that mixed ruthless practicality with strikingly eccentric ideas.

Weapons disguised as souvenirs

Among the more exotic devices were items designed not to be planted by agents at all, but sold directly to the enemy. Faithful reproductions of Balinese wood carvings were cast entirely from solid explosive, mounted on wooden bases, and fitted with time delay fuses. Native agents were encouraged to pose as hawkers along quaysides, selling the carvings as souvenirs to Japanese troops about to embark on ships. At some point after purchase, the carving would detonate.

Other devices targeted infrastructure more directly. Fake coal was produced in more than 140 shapes, carefully moulded, filled with plastic explosive, coated in black shellac, and dusted with real coal. When shoveled into a locomotive or factory furnace, it would explode with enough force to damage boilers and bring rail traffic to a halt. One SOE report dryly noted that this would at least make the profession of locomotive driver highly unpopular.

For operations in Italy, false Chianti bottles were manufactured from thick celluloid, painted green to resemble glass, wrapped in raffia, and fitted with authentic labels. The neck of the bottle could be filled with real wine to complete the illusion. Inside, both halves were packed with plastic explosive and detonators. To anyone inspecting it casually, it looked like an ordinary bottle of cheap wine.

There were also small scale devices intended to disrupt daily life. Itching powder was designed to be applied inside underclothing, where it produced maximum misery. Cream that frosted glass within minutes could obscure shop windows or vehicle windscreens. Deodorants were developed to confuse dogs tracking escaped prisoners or agents on the run. Even suicide pills were engineered with coatings that remained harmless unless chewed, allowing them to be hidden in the mouth without risk.

Against this background of inventive sabotage, the explosive rat emerged not as an outlier, but as a logical extension of SOE thinking.

Conceiving the explosive rat

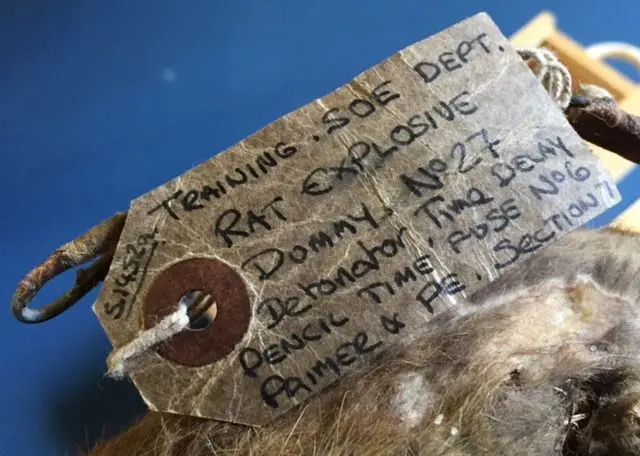

The idea for the explosive rat was developed in 1941. The concept was macabre but technically simple. Rats were a common nuisance in boiler rooms, factories, power stations, and locomotive depots. Dead rats were routinely found among coal supplies. When discovered, they were almost always disposed of by throwing them into the furnace.

SOE planners realised that this habitual response could be exploited. A rat carcass could be packed with a small amount of plastic explosive. If it was shovelled into a boiler fire, the heat would trigger the charge. While the explosive itself was modest, the real danger lay in what followed. A breach in a high pressure steam boiler could cause a catastrophic secondary explosion, damaging machinery, killing workers, and shutting down production for weeks.

To prepare the devices, SOE procured around a hundred rats from a London supplier. An officer posed as a student who needed them for laboratory experiments, a deception that raised no suspicion. The rats were killed, skinned, hollowed out, filled with plastic explosive, and carefully sewn back together. From the outside, they looked like nothing more than unpleasant refuse.

Some designs allowed for delayed fuses, adding flexibility in how they could be deployed. The intention was to place the rats among coal piles in industrial sites across occupied Europe, where their discovery would be inevitable and their disposal predictable.

A weapon that was never used

In operational terms, the explosive rat never fulfilled its original purpose. The first shipment of prepared carcasses was intercepted by German forces before it could be distributed. The operation was abandoned, and no confirmed boiler explosions were caused by rat bombs.

Later claims that several Belgian factories were damaged by explosive rats appear to be myths rather than documented fact. SOE files themselves make no such claims, and historians generally agree that the devices were never successfully deployed in the field.

Yet in a strange reversal, the failure of the operation turned into one of its greatest successes.

Panic, paranoia, and unintended victory

When the Germans intercepted the shipment, they were reportedly fascinated and alarmed by the idea. The rats were displayed at German military schools as examples of British sabotage methods. Instructions were issued to be vigilant for further booby trapped rodents. Searches were organised across occupied territory, with personnel ordered to inspect coal supplies and boiler rooms for suspicious carcasses.

SOE officers later noted that this reaction consumed far more enemy time and resources than the original plan ever could have. Factories were disrupted not by explosions, but by inspections. Workers became nervous about handling coal. Engineers wasted hours checking for a threat that did not, in fact, exist.

An internal SOE assessment concluded bluntly that the trouble caused to the enemy was a much greater success than if the rats had actually been used. The weapon had worked, but at a psychological level rather than a physical one.

This was a lesson that reinforced one of SOE’s core beliefs. Sabotage was as much about fear and uncertainty as it was about destruction. If the enemy could be made to suspect that anything might be dangerous, efficiency would collapse under the weight of caution.

Sceptics and supporters in Whitehall

Not everyone in Britain was convinced by the SOE’s methods. Early on, some Whitehall officials and senior military figures dismissed the organisation as a cloak and dagger party with little relevance to the real war. To them, exploding rats and fake wine bottles seemed frivolous compared to tanks and aircraft.

This scepticism gradually faded as reports came in from occupied Europe. Resistance movements valued the equipment, and the disruption it caused was measurable. The SOE also drew on expertise from other agencies. MI5 and Scotland Yard provided advice on lock picking, burglary, and evasion. Criminal techniques, refined for wartime use, became tools of national survival.

By the later years of the war, SOE had recruited around 10,000 men and 3,200 women. Of the roughly 6,000 agents sent into occupied Europe, North Africa, and Asia, about 850 were killed in 36 countries. The whimsical nature of some devices should not obscure the very real risks faced by those who carried them.

Legacy of a dead rat

Today, the explosive rat has become one of the most enduring symbols of SOE ingenuity. It is frequently cited in museums, documentaries, and histories as an example of how unconventional thinking shaped the hidden war of sabotage.

Its story also reveals something deeper about the conflict. The Second World War was not fought solely through grand strategy and industrial might. It was also waged through imagination, psychology, and an intimate understanding of human habit. The explosive rat relied not on technical brilliance alone, but on a simple insight into how people behave when faced with something unpleasant.

In that sense, it stands alongside the fake coal, the Chianti bottles, and the Balinese carvings as part of a coherent philosophy. Ordinary objects, carefully altered, could become weapons. Fear could be as disruptive as fire. And sometimes, the mere suggestion of danger was enough to bring an enemy system grinding to a halt.

The rat never exploded in a German boiler. Yet it did exactly what it was meant to do. It made the enemy look at the mundane world around them and wonder what else might be waiting to blow up.

Comments