The African Choir in Victorian Britain

- Jan 15

- 8 min read

It began, as so many Victorian ventures did, with careful planning and a confidence that Britain knew how to organise the rest of the world. When the African Choir arrived in the United Kingdom in 1891, they were presented as living proof of missionary success and imperial benevolence. Yet behind the polished concerts and earnest speeches sat a far more layered story, one that only really emerges when you slow down and listen to the voices of the singers themselves.

Between 1891 and 1893, fourteen young men and women, accompanied by two children, travelled from South Africa to Britain under the name of the African Choir. South Africa at that time was firmly under British colonial rule, and the social landscape they left behind was shaped by expanding mining operations, railways, and an industrial economy that relied heavily on black labour while offering limited opportunities for advancement.

The stated aim of the tour was to raise funds for a technical college on the Cape Coast. The idea was pragmatic rather than idealistic. Mission education had produced a generation of literate, skilled African men and women, but there were few institutions that could offer advanced technical training. A college of this kind promised to equip black workers with skills that colonial administrators increasingly relied upon, while still keeping education within acceptable limits.

Most members of the choir were educated Christians, many of them trained at Lovedale College. Lovedale was more than a school. It was a carefully constructed social experiment. Founded by the Glasgow Missionary Society, it combined religious instruction with vocational training, producing teachers, clerks, telegraphists, and artisans. Graduates were encouraged to see themselves as moral exemplars, disciplined and industrious, able to move between African communities and colonial institutions.

The African Choir was, in many ways, a public demonstration of this philosophy.

Who controlled the story

At each performance, audiences were first addressed by the choir’s manager or musical director. Newspaper reports make it clear that these figures were white Europeans, and their role was to explain the choir’s purpose, reassure audiences of their respectability, and frame the singers in ways that Victorian sensibilities could comfortably absorb.

The singers themselves rarely spoke from the stage. Their presence was mediated, their stories summarised, their achievements presented as outcomes of missionary guidance rather than personal determination. This was not unusual. Victorian philanthropy depended on hierarchy. Charity flowed downward, and gratitude was assumed to flow back up.

Yet when the singers were interviewed directly, a very different picture emerged.

Royal approval and imperial stages

Early in the tour, the African Choir performed for Queen Victoria at Osborne House on the Isle of Wight. This was not simply a social honour. Royal approval acted as a stamp of legitimacy, signalling to audiences and donors that the choir was worthy of attention and support.

From there, they moved on to larger public venues, including Crystal Palace. The Crystal Palace was a space steeped in imperial meaning. Built to house the Great Exhibition, it functioned as a showroom of global progress, empire, and hierarchy. Performing there placed the African Choir within a long tradition of imperial display, even if their role was more active than most.

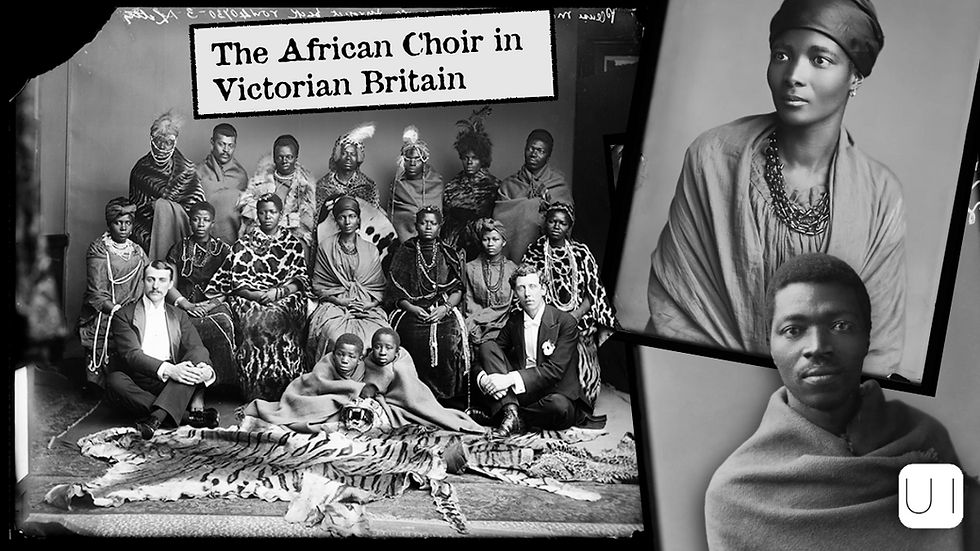

Photographs taken by the London Stereoscopic Company captured the visual contradictions at the heart of the tour. In some images, the singers appear in contemporary Victorian dress, standing stiffly in neat rows. In others, they wear stylised African clothing, adorned with beads, animal skins, and theatrical props chosen to emphasise difference.

These images circulated widely, reinforcing the idea that the choir embodied both civilisation and exoticism. The contrast was deliberate, and it sold tickets.

Among the most revealing documents of the tour are the interviews published in the Illustrated London News on 29th August, 1891. These first person accounts disrupt the neat framing offered on stage.

Paul Xiniwe

I was born in November 1857, of Christian parents. I attended school from my youth and contributed in some measure to the cost of my education by doing some domestic work for an English family before and after school hours. This materially assisted my mother in paying the school fees and for my clothing.

At fifteen years of age I left school and entered the service of the Telegraph Department as a lineman having to look after the poles and wires, and to repair breakages by climbing poles in monkey-like fashion. Being transferred to the Graaff Reinet Office, 130 miles from home, I had to go there alone without any knowledge of the road, or of any person there; but I got there in three days, travelling on horseback.

The officer in charge at Graaff Reinet found my handwriting better than that of the European clerks, and, in consequence, gave me his books to keep, with additional pay, and any amount of liberty in and about the office. This was a privilege which I highly valued and turned to the best advantage by studying the code-book, taking them home to pore over them at night, and coming to the office about two hours before opening time, as I kept the keys, to learn, privately, the art of telegraphy. I surprised the mater and clerks one day by telling them that I could work the instrument, and to dispel their serios bouts went through the feat to their great astonishment, but happily, also, to the pleasure of my master.

After three years’ service I left the post of lineman, quitted Graaff Reinet, and was employed on the railway construction as telegraph clerk, timekeeper and storekeeper: a highly respectable and responsible post of a native to hold. When I left school and home I only had a little knowledge of the “three Rs”; but I was assiduous in improving my learning and seeking to qualify myself for a higher position. I had now, earned a good sum of money on the railway, as well as a good name, as the testimonials I hold from there could show.

Still desirous of greater improvement, I went to Lovedale, and held the office of telegraphist also in that institution, which helped me to pay my college fees. I stayed there two years, and passed the Government teachers’ examination, being one of only two who passed from the institution out of twenty-two candidates presented. I then took charge of a school at Port Elizabeth, which I kept for four years, and which I gave up to carry on business at King William’s Town, until the period of my joining the “African Choir”.

Makhomo Manye (born 7 April 1871)

"My father is a Basuto of the Traansvaal, and my mother an Umbo, the people commonly known as Fingos. Both are Christians of the Independent Church; my father is a local preacher of that church. I was brought up at Uitenhage and at Port Elizabeth, where I got my schooling under efficient teachers, who passed me through the Government requirements of mission schools. My parents being unable to send me to one of the girls’ high school, I therefore had to stay and work under mistresses.

We left Port Elizabeth and came to Kimberley, where after two years or a little more, I was engaged as an assistant teacher and sewing mistress in a Wesleyan Government-aided school; there I served for a year. During my stay there, a Government Inspector visited our school and gave a favourable report of its condition; he spoke in high terms of the lower section, which was under my supervision. During my time of service in the above school, we had local concerts, in which I was the conductor’s assistance and leading voice. I resigned, through unavoidable circumstances, and joined the African Choir.”

Johanna Jonkers

"The little I know of my parents is that they were taken captives by the Dutch which they were about twelve years of age. They were badly treated by the Dutch, till it happened that some good friends pitied my mother, and advised her to go to the town, and she was waiting outside when she met a gentleman who passed her three times that day. At last he spoke with her, and bade her come to his house. She went with him, and told him, as she reached the house, that she came from a farm-house where the Dutch people were very hard and cruel to her.

The new friends who now received her, being very sorry to hear her sad story, took good care of her, and she stayed with them till she got married and had a happy life. I was born here, at Burghersdorp; my parents were Christians."

Josiah Semouse

"I was born in 1860 at Mkoothing, in what is now known as one of the conquered territories (Basutoland). My parents being Christian people, I was naturally so brought up; I first attended school at a small village called Korokoro, where my father was appointed local preacher, and there I learnt to read and write my own language. Then I went to the Morija training institution, about thirty-six miles from my home. I heard from a native teacher that there is a school in Cape Colony, called Lovedale, which is famous for the practical knowledge that it imparts in its pupils. But, a few months after, war broke out between Basutoland and the Cape Colony about the order of disarmament.

I took part against the British during this war, but I was not happy, because I did not know the English language then. When the war was over, which was decided in our favour, I left Basutoland for Lovedale, travelling day and night; I slept for a few hours till the moon came out, and then pursued my course, till I reached my destination in eleven days, the whole distance being about 400 miles.

At Lovedale I received both education and civilisation; then one day, in March 1886, the principal of the college received a telegram from Kimberley to say that there was a vacancy in the office there for an honest, educated young man. I was sent to fill up the vacancy, and I remained there till the end of March 1891, when I received an esteemed offer from the manager of the African Choir to join the choir for England.

We left Kimberley on April 10, and called at several towns as we proceeded. On May 20 we embarked at Capetown in the Warwick Castle; during the first two days we were sea-sick, but I was the first one to get over it, and I became a general servant of the choir till they all got better, I had a pleasant voyage till we landed on the English shore on June 13. In England, I was very much surprised by many things. The trains running at the tops of the houses in London, much faster than railway trains to in South African, especially struck my notice.

Wandering about this big city, which seems endless, I admired St Paul’s Cathedral and the Houses of Parliament; I have visited the British Museum, the South Kensington Museums, the Zoological Gardens, the Crystal Palace, and other places. What I have see here is more than all I had every heard of before. I am the correspondent of a Basuto paper, but I doubt whether its readers will believe the reports in my writing, as everything is so wonderful here."

What Victorian audiences never heard

One of the most significant details often omitted from celebratory accounts is that the tour did not achieve its financial goals. The proposed technical college was never built. Funds were depleted by touring costs, management decisions, and exploitative contracts. Some choir members found themselves stranded in Britain longer than expected, forced to take on additional work to survive.

This outcome sits awkwardly alongside the language of philanthropy that surrounded the tour. The African Choir generated admiration, income, and cultural capital, but much of that value did not flow back to the singers themselves.

What remains, more than a century later, is a record of individuals navigating empire with clarity and resilience. They were not curiosities or passive beneficiaries. They were workers, educators, writers, and organisers who understood exactly what they were doing, even when the system around them refused to fully acknowledge it.

Comments