How Jacques Henri Lartigue Influenced Wes Anderson’s Films

- Daniel Holland

- 6 hours ago

- 6 min read

The influence of Jacques Henri Lartigue on the films of Wes Anderson is unusually well documented. Anderson has never been coy about it. He has named Lartigue directly, pointed to specific photographs, and even woven Lartigue’s family history into his own fictional worlds. What matters, though, is not just that Anderson admired Lartigue’s images, but that he recognised a shared way of looking at the world. Quietly. Affectionately. With an attention to enthusiasm that never tips into mockery.

Rather than borrowing a surface aesthetic, Anderson absorbed something more personal from Lartigue: a belief that private obsessions, youthful intensity, and small acts of invention are worthy of serious attention.

A private archive that took decades to surface

Lartigue began taking photographs in 1901, when his father gave him a camera at the age of seven. From that point on, he photographed constantly, but almost entirely for himself. He assembled albums filled with prints and handwritten notes, creating a detailed record of his daily life and inner moods.

For most of the twentieth century, this work remained unseen beyond family and friends. Lartigue did not pursue photography professionally and thought of himself primarily as a painter. It was only when he was 69 years old that an American curator took a serious interest in his photographs, leading to exhibitions and publications that revealed the scale of his archive.

That long period of obscurity matters when thinking about Wes Anderson. Anderson’s films often feel like carefully protected worlds, governed by their own internal rules. Clubs, institutions, research projects, and family systems take on outsized importance because the characters invest them with meaning. Lartigue’s albums operate in much the same way. They exist because they mattered to him, not because they were meant to be seen.

Rushmore and the influence stated plainly

Anderson first acknowledged Lartigue publicly in the press materials for Rushmore in 1998. Describing the tone he was aiming for, he explained that he wanted the film to feel slightly unreal, shaped by how Max Fischer sees his school, a place he loves far more intensely than anyone else around him.

To arrive at that feeling, Anderson and his collaborators looked at period films, but they also turned to photography. As Anderson put it:

“We looked at some pictures by photographer Jacques-Henri Lartigue, who reminds me of Max, and that became a part of it.”

This comparison is revealing. Anderson was not simply drawn to how Lartigue’s photographs looked. He recognised a shared temperament. Like Max Fischer, Lartigue approached the world with seriousness, enthusiasm, and an almost anxious desire to hold onto moments before they slipped away.

The reference appears inside the film itself. Early in Rushmore, just after the curtains open to reveal the name of Rushmore Academy, the camera pans across a classroom blackboard. Taped to it are reproductions of Lartigue photographs. They pass by quickly, blurred by the movement of the camera. They are present without being underlined.

That fleetingness feels deliberate. Lartigue’s influence is there, but it does not announce itself.

Maurice Lartigue and the origin of Zissou

One of the most concrete links between Lartigue and Anderson arrives in The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou in 2004. When the film opened in France, Anderson explained that the name Zissou was not invented arbitrarily. It was a direct reference to Maurice Lartigue, Jacques Henri’s older brother.

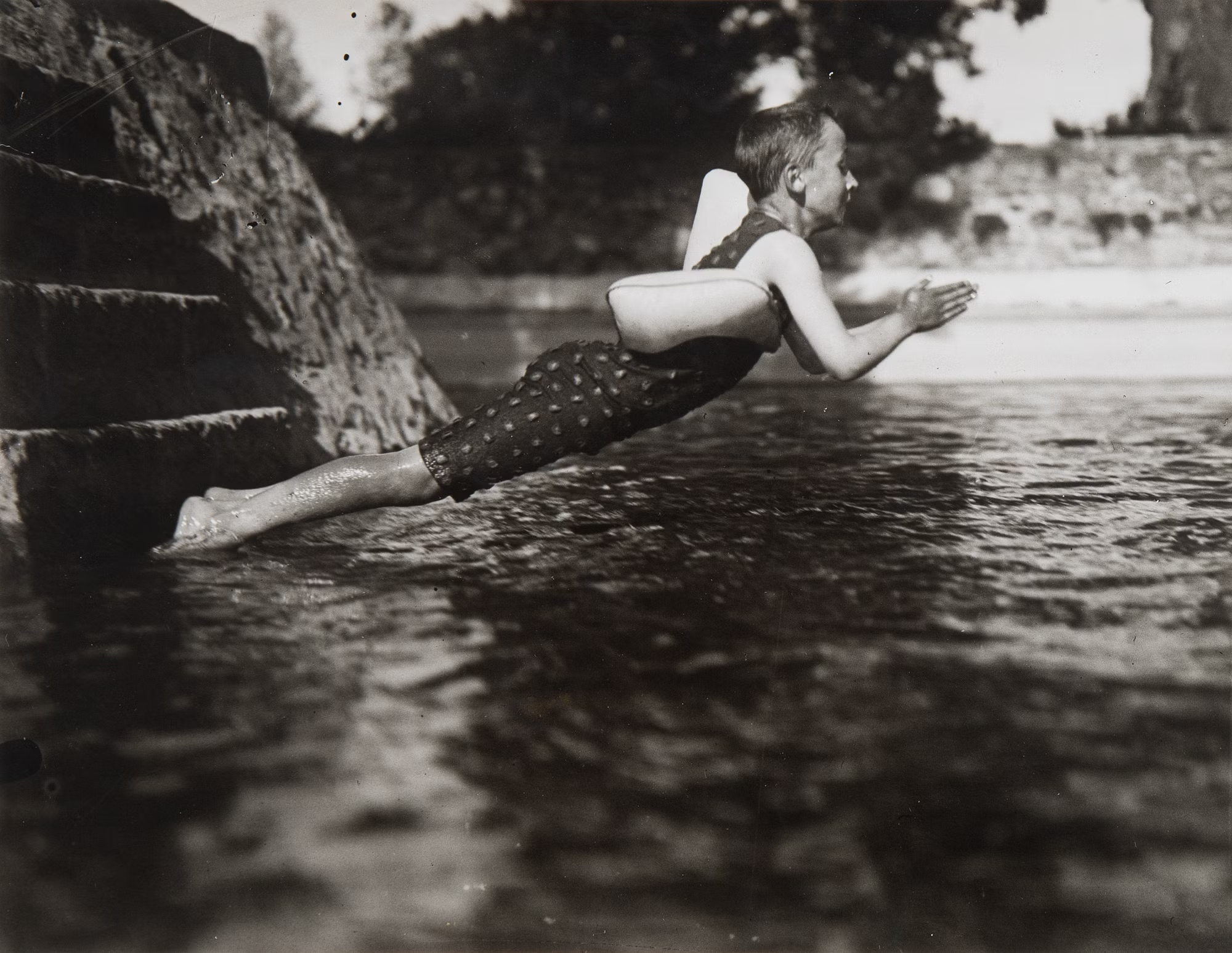

Maurice was a constant presence in Lartigue’s early photographs. Where Jacques observed, Maurice acted. He was restless, inventive, and physically fearless. As a boy and young man, he built machines, modified vehicles, and attempted stunts that were as ambitious as they were ill advised.

He constructed homemade gliders from wood, fabric, and wire, launching himself from hills in early attempts at human flight. The results were often clumsy and dangerous. Photographs show awkward take offs and inevitable crashes. Maurice survived largely through resilience and luck rather than engineering success.

He was equally fascinated by speed on the ground. At a time when automobiles were still experimental and unreliable, Maurice raced them, rode in them, and tested their limits. Jacques Henri photographed these moments obsessively, producing images where wheels tilt, bodies lean forward, and motion warps the frame.

Many of Lartigue’s most famous photographs show Maurice airborne. Jumping from stairs. Leaping over obstacles. Caught at the exact instant when gravity briefly loosens its hold. These were not staged tricks. Maurice genuinely enjoyed throwing himself into space. The nickname Zissou became associated with this behaviour, suggesting speed, mischief, and confidence.

When Anderson spoke about Maurice in 2005, he described him as “absolutely brilliant” and “a casse cou fini”, a complete risk taker. Steve Zissou is not a literal daredevil in the same way, but the name connects the character to that earlier spirit of enthusiasm and invention. It is a tribute rather than an adaptation.

The connection deepens further when a 1919 self portrait by Jacques Henri Lartigue, titled Moi au Cap du Dramont, appears in The Life Aquatic. In the film, Steve Zissou identifies it as a photograph of his deceased mentor, Lord Mandrake. The image itself is unchanged. Its meaning is reassigned, quietly folding Lartigue into the film’s fictional history.

Lartigue’s name appears in the end credits of both Rushmore and The Life Aquatic, reinforcing that this is not coincidence or private homage. It is acknowledged influence.

In its issue of November 29, 1963, Life magazine features numerous photos by Jacques Henri Lartigue. A cropped version of the photo depicting the flight of the ZYX 24 is reproduced on p. 69 along with the following comment:

Having given a big push and jump, Maurice dangles from the bottom of his 22nd glider. A friend is helping by holding wings level, while another is pulling desperatly at the rope disappearing off the right edge of the picture. Longest Lartigue flight was about a minute

There are a number of additional photos by Jacques Henri showing his brother’s various attempt at getting airborn.

In another book simply title Jacques-Henri Lartigue (New York: Aperture, 1976) Ezra Bowen comments the same photo in her introduction:

Does anything say more of the dreamlike excitement of that time, of the confidence and romantism of the people? Or indeed of the sure eye and brilliant sense of timing of the sixteen-year-old photographer who not only captured the moment, but saw in it the combination of verve and marvelous farce that are part of so many of his other pictures? (p. 6)

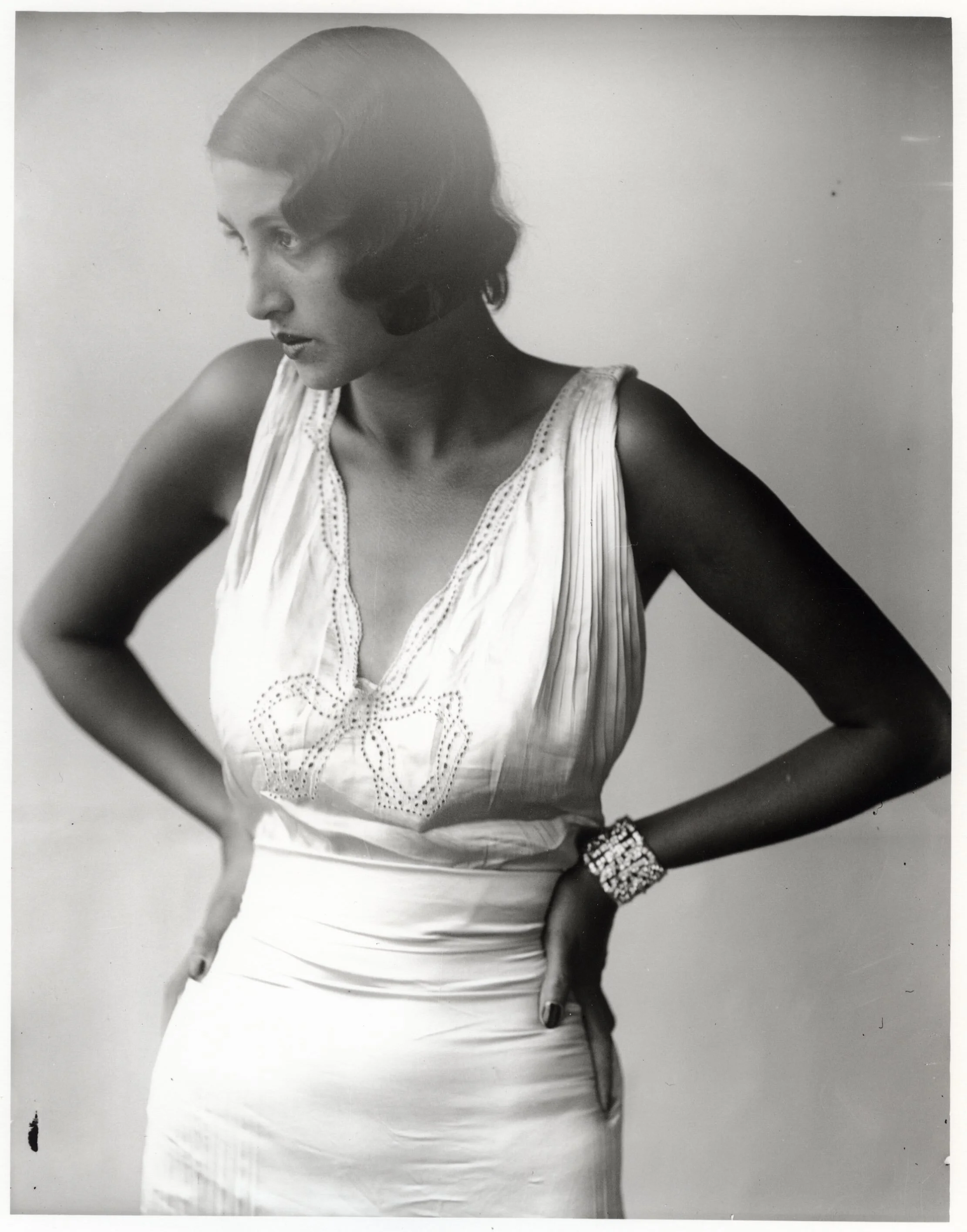

Next, in the upper right corner is another photo of Zissou in one of his curious invention: the tire boat.

Wonder without irony

Lartigue’s photographs are often described as joyful, but that joy is not naive. He lived through two world wars and a global economic depression, yet his camera consistently turned toward lightness, movement, and beauty. This was not denial so much as selection. He chose what to hold onto.

A 1974 Aperture publication put it succinctly:

“Lartigue’s eye was simply not tuned to any of life’s horrors and ugliness.”

Anderson’s films make a similar choice. They are not unaware of grief, disappointment, or failure, but they refuse to linger on cruelty. Characters suffer, but the films remain attentive to how they protect themselves emotionally. That restraint can be traced directly back to Lartigue’s example.

Composition, control, and emotional space

Lartigue’s photographs are carefully composed without feeling rigid. Movement runs through them. People jump, run, and lean forward. Cars streak past. The frame holds steady while energy passes through it.

Anderson’s cinema extends this idea into motion. His frames are controlled, often symmetrical, but within them characters move, argue, perform, and retreat. Because the composition is stable, the viewer is free to notice small emotional shifts. This balance between order and motion mirrors Lartigue’s photographic instincts.

Childhood taken seriously

Children in Lartigue’s photographs are not sentimental figures. They are active, inventive, and occasionally reckless. Childhood is presented as a state of intense engagement with the world.

Anderson treats childhood in much the same way. Characters like Max Fischer are not framed as innocent or immature. They are serious, driven, and emotionally complex. Adults, by contrast, often appear tired or uncertain. This inversion echoes Lartigue’s world, where youthful energy dominates the frame.

A shared discomfort with spectacle

Neither Lartigue nor Anderson seems particularly interested in spectacle for its own sake. Even when Anderson constructs elaborate sets or sequences, they serve character rather than overwhelming it. Lartigue avoided photographing catastrophe even when history offered it in abundance.

Both artists favour attention over drama. The result is work that feels intimate rather than impressive.

Closing thoughts

Jacques Henri Lartigue did not photograph with cinema in mind. Wes Anderson did not turn photographs into films. Yet their work meets naturally, bound by a shared respect for enthusiasm, private worlds, and fleeting happiness.

The reference to Zissou makes that connection explicit. Behind Anderson’s fictional oceanographer stands a real young man throwing himself into the air at the dawn of the twentieth century, photographed by a brother who understood that moments like that do not last.

What links them is not style, but temperament. A belief that joy, however brief, is worth noticing carefully.