What Caused the Kentucky Meat Shower of 1876?

- Jan 14

- 5 min read

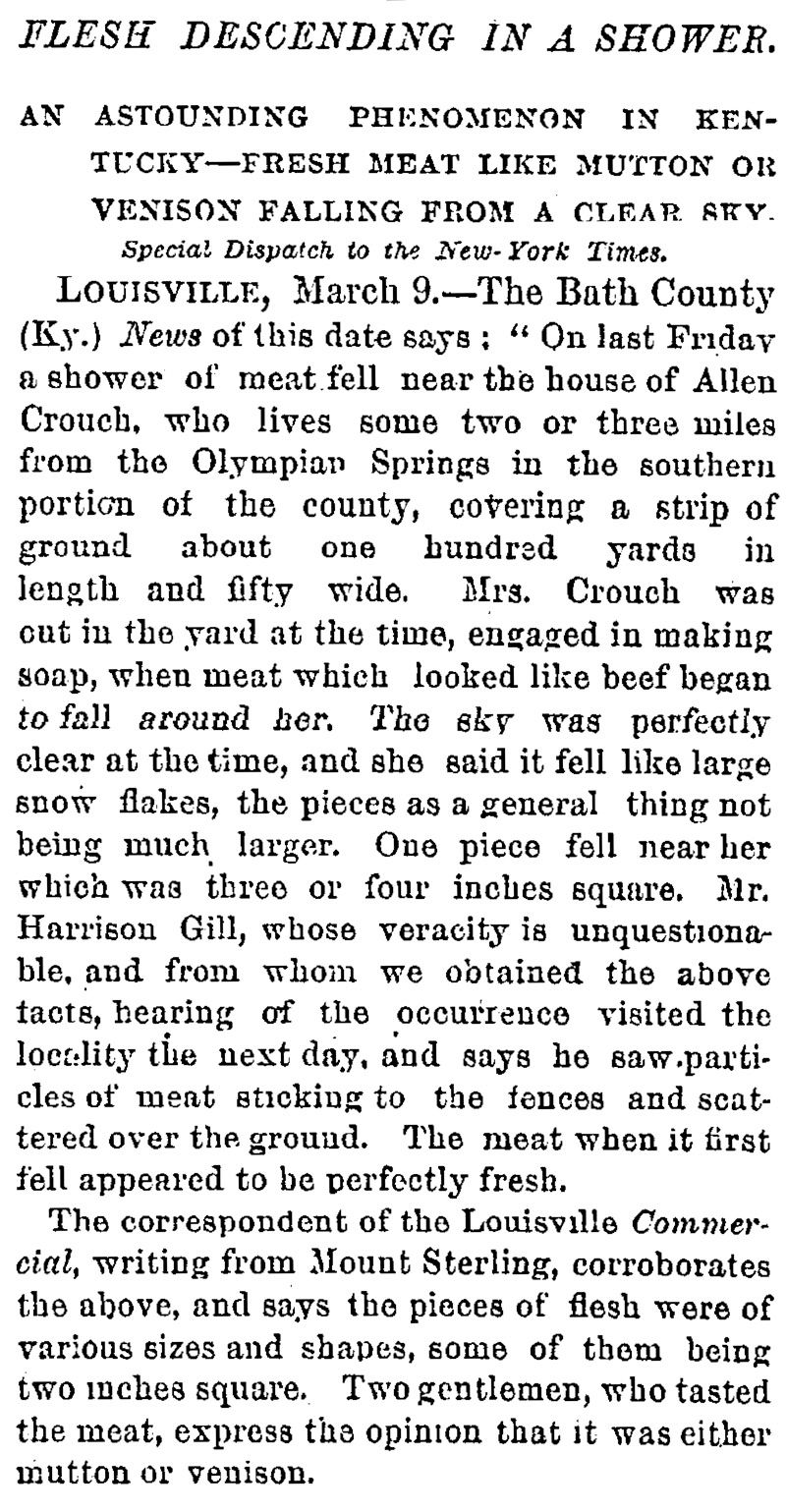

It was shaping up to be an entirely forgettable late morning in rural Kentucky. The sky was blue, the sun was doing what it always did, and nobody had any reason to look upwards. And then, without ceremony, the sky began dropping meat.

Not metaphorical meat. Not symbolic meat. Actual chunks of raw flesh.

This happened on the 3rd of March, 1876, near Olympia Springs, a quiet farming area where unusual events tended to involve stubborn livestock rather than surprises from above. What followed lasted only a few minutes, but it left behind a story so odd that people are still trying to decide whether it is more unsettling or faintly ridiculous.

A calm morning that took a turn

The first witness was Mrs Crouch, wife of local farmer Allen Crouch. She was outside the house making soap, which already tells you this was not a woman prone to panic, when pieces of something began landing nearby.

“Between 11 and 12 o’clock I was in my yard, not more than forty steps from the house,” she later told reporters. “There was a light wind coming from the west, but the sky was clear and the sun was shining brightly. Without any prelude or warning of any kind, the shower commenced.”

What fell was recognisably meat. Fresh, red, and solid. Some pieces were light enough to drift down gently. Others were several inches long. It continued for several minutes. Then it stopped. The sky returned to its earlier innocence, as if nothing unusual had happened at all.

Except, of course, the ground was now littered with flesh.

Surveying the damage

As neighbours gathered, they began to realise the scale of it. An area roughly one hundred yards long and fifty yards wide had been peppered with meat. It lay on fences, dotted the yard, and even landed on the farmhouse itself.

Some witnesses said the pieces made a snapping or slapping sound when they hit the ground. Others noticed the smell straight away. Joe Jordan, a local grocer, described it as “offensive to the extreme, like that of a dead body.” This would later cause problems for one popular scientific explanation.

At first, the Crouch family wondered whether the event had religious significance. That reaction did not last long. Curiosity took over, followed closely by argument.

The great meat debate

The next question was simple enough. What kind of meat was it.

Opinions varied. Many locals thought it looked like beef. A hunter disagreed, pointing out its greasy texture and suggesting bear. This disagreement might have ended there, but several men decided to settle the matter in the most nineteenth century way possible.

They tasted it.

Two experienced hunters fried and sampled pieces, concluding that it was either venison or mutton. Unsatisfied, a butcher was consulted. He also tasted it and dismissed all previous suggestions, stating that it tasted “neither like flesh, fish, nor fowl.”

It is worth pausing here to appreciate that multiple people voluntarily ate unidentified meat that had fallen out of the sky. This detail is sometimes glossed over, but it deserves emphasis. The Kentucky Meat Shower is not just a story about confusion and science. It is also a reminder that people in the 1870s were, by modern standards, remarkably unfussy.

Calling in professional opinions

With local expertise exhausted, samples were collected and sent to chemists and universities. Newspapers picked up the story, including Scientific American and The New York Times, and suddenly a small Kentucky farm was at the centre of national attention.

Early tests confirmed that the material was animal tissue. One chemist believed it was mutton. Another agreed it was meat but insisted it was not sheep. The arguments were polite but unresolved. Attention shifted to a more awkward problem.

If this really was meat, how had it ended up in the sky.

Ideas ranging from earnest to absurd

Some responses were playful. William Livingston Alden, writing in The New York Times, suggested that just as the Earth passes through belts of meteors, it might also pass through a belt of venison and mutton orbiting the sun. He followed this with an even darker joke, proposing that the meat could be the remains of Kentuckians caught up in a violent whirlwind during a knife fight.

These ideas were not serious, but they captured the mood. Even educated observers were struggling to frame the event in ordinary terms.

The algae that was not algae

One serious explanation came from chemist Leopold Brandeis, who suggested the substance was Nostoc, a type of cyanobacteria. Nostoc can swell into a jelly like mass after rainfall, sometimes giving the impression that it has fallen from the sky.

Unfortunately for this theory, there had been no rain. Mrs Crouch and others were adamant that the sky was clear and the sun was shining. Later writers, including Charles Fort, would point out that without rain, the Nostoc explanation simply did not work.

What microscopes revealed

As samples circulated, scientists began examining them more closely. Several doctors and microscopists studied the tissue and published their findings.

They did not simplify matters. Some pieces were identified as striated muscle. Others were cartilage or connective tissue. Several samples were identified as lung tissue. Allan McLane Hamilton reported that the structure matched mammalian lung, possibly from a horse. He even remarked on its similarity to human lung tissue, a comment that was noted and quietly ignored.

At this point, one thing became clear. This was not algae. It was not frog spawn. It was definitely animal tissue, and it had arrived from above.

The explanation nobody loved

The most convincing explanation turned out to be the least appealing. Kentucky had large populations of turkey vultures and black vultures. These birds feed communally on carcasses and are known for eating quickly and enthusiastically.

When startled, vultures regurgitate what they have eaten. It lightens them for rapid escape and acts as a deterrent. Crucially, when one bird does this, others in the flock often follow.

As one contemporary observer explained, when one vulture begins “the relief operation,” the others are soon “excited to nausea,” producing a sudden shower of half digested meat.

It was not a graceful solution, but it fit the evidence. The mixture of tissues made sense. So did the greasy texture, the smell, and the limited area affected. It also neatly explains why several people unknowingly tasted what was, in all likelihood, vulture vomit.

That detail does not appear to have troubled anyone at the time.

A story that would not go away

For years, the Kentucky Meat Shower survived as a curiosity. Then, in 2004, it gained a second life. During a clear out at Transylvania University, art professor Kurt Gohde discovered a small glass vial labelled “Olympia Springs.” Inside was a preserved piece of meat from the original event.

The specimen is now housed at the Moosnick Medical and Science Museum in Lexington, Kentucky. Modern DNA testing was attempted, but the age and condition of the sample meant that no specific species could be identified. Even so, its existence confirms that the story was not exaggerated.

Something tangible really did fall from the sky.

From alarm to local pride

Today, the meat shower has become part of Bath County folklore. The Bath County History Museum has displayed the preserved sample, and recent anniversaries have been marked with exhibitions and festivals. There has even been a mystery meat chilli cook off, which suggests that time has softened people’s feelings about the whole affair.

So what actually happened

The most likely explanation remains that a flock of vultures, disturbed while feeding, regurgitated partially digested animal tissue while in flight on the 3rd of March, 1876. The meat then fell over farmland near Olympia Springs under clear skies.

It was not divine intervention or cosmic mishap. It was an ordinary biological response witnessed under very unusual circumstances.

And yes, people ate it.

The sky did not rain meat. Birds did.

Comments