Bettie Page Between Innocence and Transgression: The Long Life of an American Icon

- Jan 9

- 8 min read

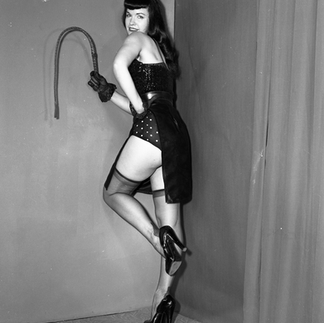

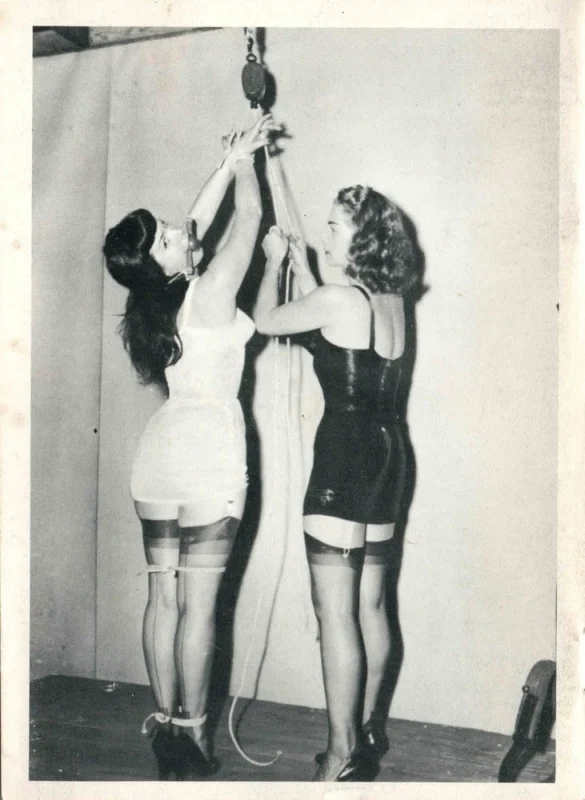

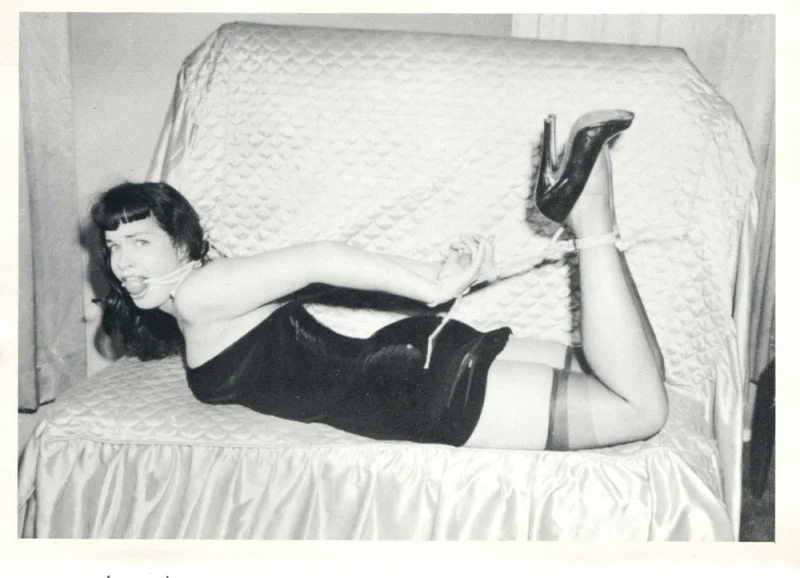

In the mid 1950s, envelopes quietly crossed the United States postal system containing small black and white photographs of a smiling woman bound with rope, gagged, or posed in carefully staged scenes of capture and restraint. They were not sold on newsstands and they were never advertised openly. Yet tens of thousands of Americans knew exactly where to send their money. The woman in those photographs was Bettie Page, and although she would later be labelled the Queen of Bondage, she never set out to be anyone’s symbol.

Bettie Page’s story is not simply one of fame and retreat. It is a study in contradiction, shaped by trauma, moral panic, religious conviction and a cultural afterlife that grew without her knowledge. Her image became a shorthand for erotic freedom, while her personal life increasingly narrowed and withdrew from the world.

Childhood and Early Trauma

Bettie Mae Page was born on 22nd April, 1923, in Kingsport, Tennessee, the second of six children in a working class family struggling through the Great Depression. Her father worked as a mechanic, and money was scarce. When Bettie was ten, her parents divorced, and she and two of her sisters were placed in an orphanage for a year. The experience left a lasting impression of impermanence and emotional restraint.

After returning home, Page was sexually abused by her father, a fact that emerged later in her life and added a painful layer to the way her adult image would be interpreted. Despite this, she excelled academically and socially. At Hume Fogg High School in Nashville, she became Homecoming Queen and earned a scholarship to George Peabody College.

She graduated in 1943 and married her high school sweetheart Billy Neal. The couple moved to San Francisco, where Page worked as a secretary and modelled on the side. Hollywood beckoned briefly, but her one screen test ended badly when she rejected a producer’s expectation that she would make herself sexually available. Years later she reflected, “I don’t mind sleeping with someone to get ahead, but I’m not going to sleep with everyone.”

The marriage collapsed in 1947. In 1948, newly divorced and restless, Page moved to New York City.

New York and the Camera Clubs

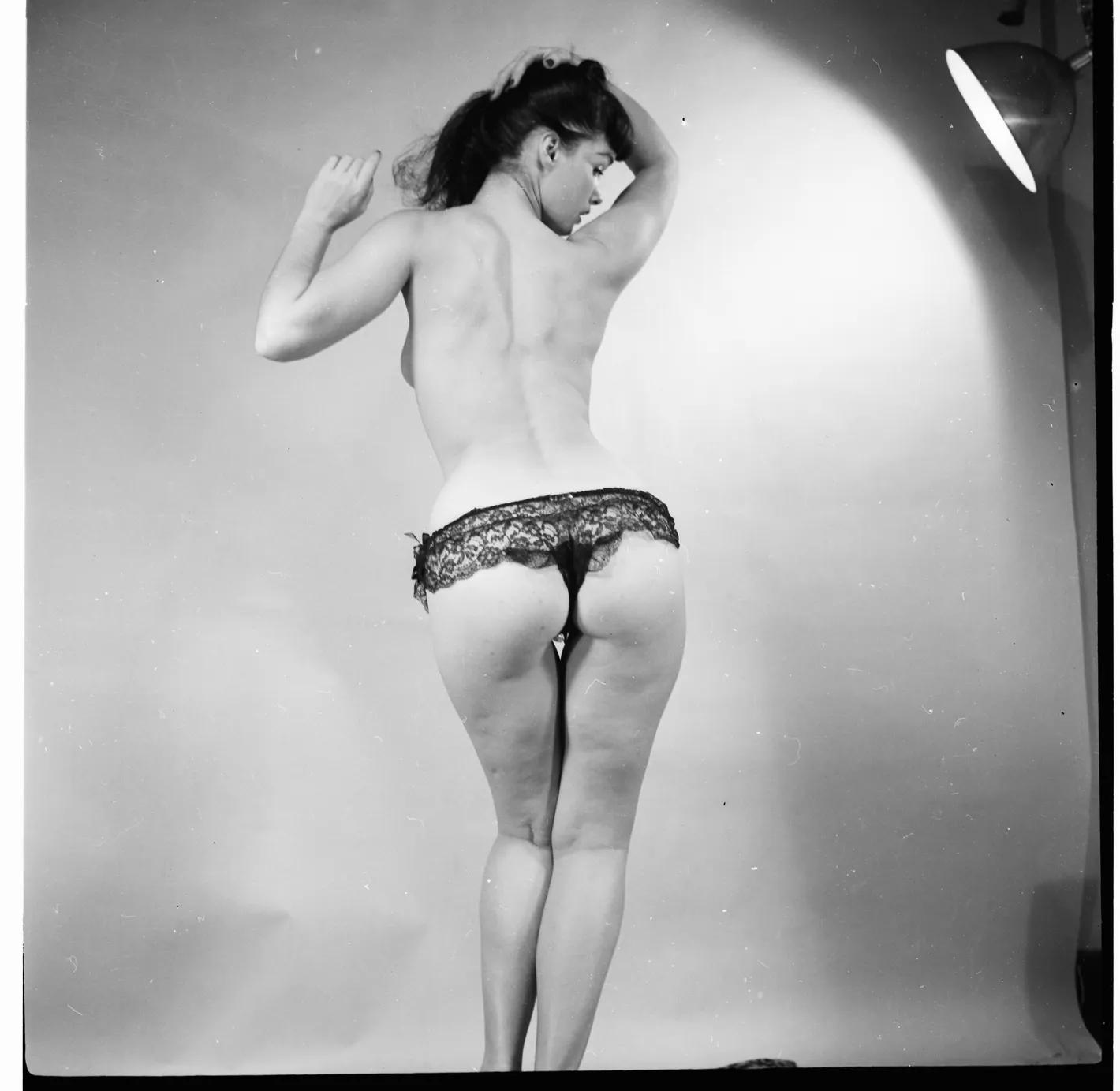

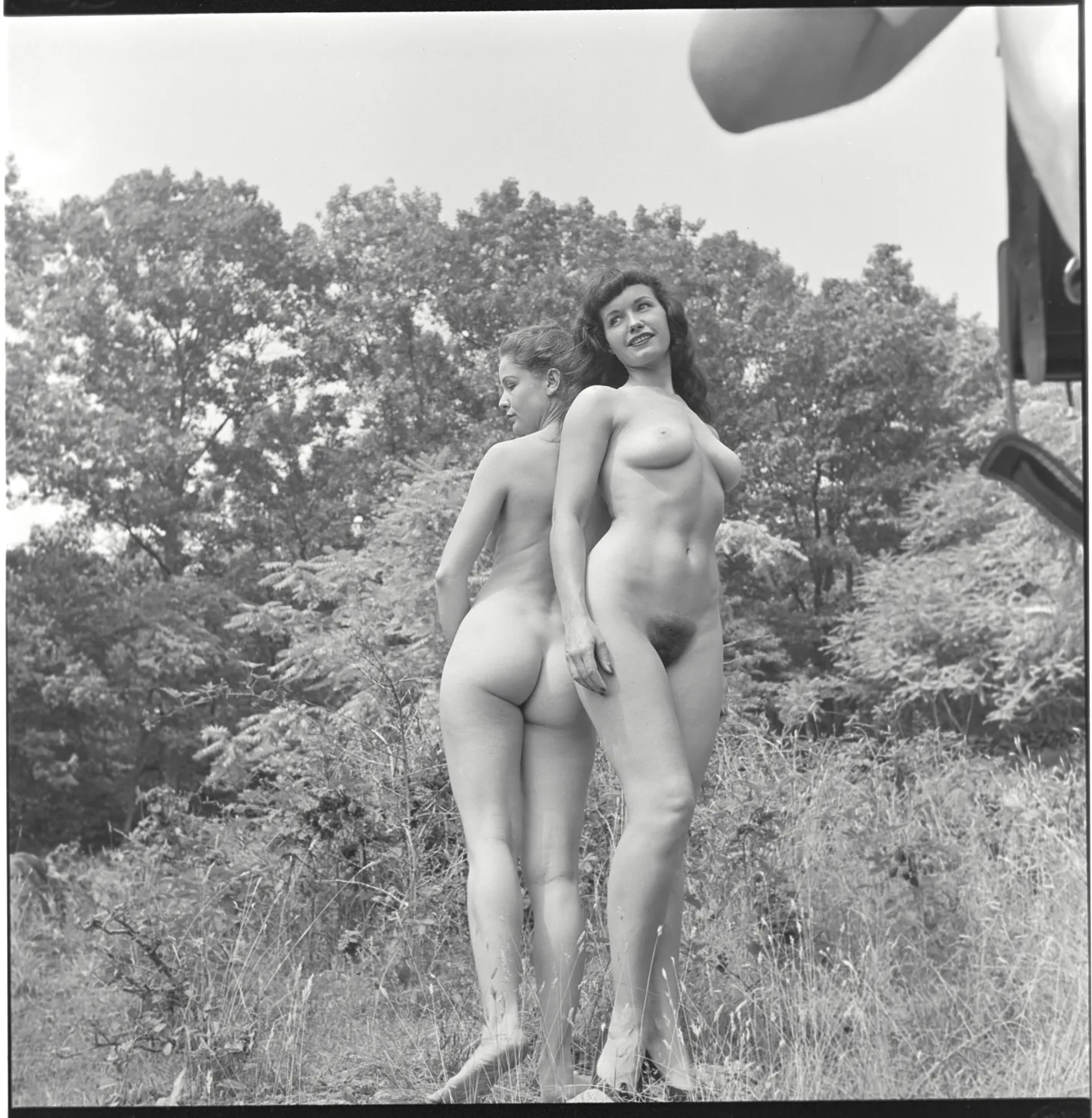

New York in the late 1940s had a thriving underground photography scene. Camera clubs, private publications and mail order catalogues existed in the grey areas of postwar morality. In 1949, Page was spotted on Jones Beach by Jerry Tibbs, a police officer who also worked as a photographer. He encouraged her to pose for nude camera club photographs, and she agreed.

The effect was immediate. Page’s direct gaze, athletic figure and distinctive dark fringe set her apart from the polished glamour of Hollywood pin ups. She appeared in magazines such as Wink and Flirt, quickly becoming a national pin up figure.

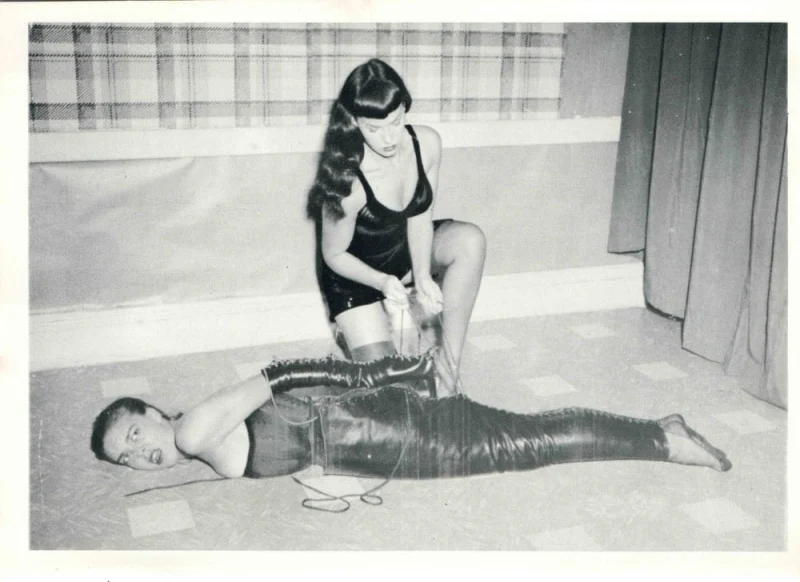

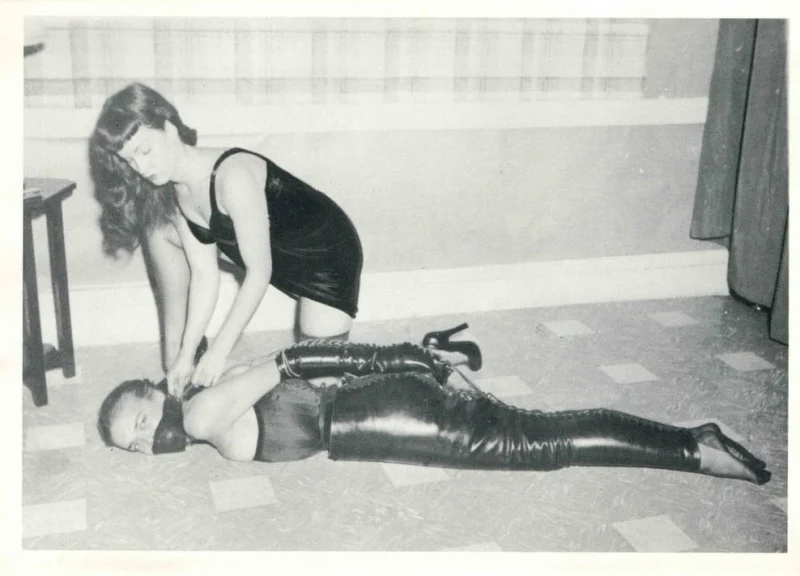

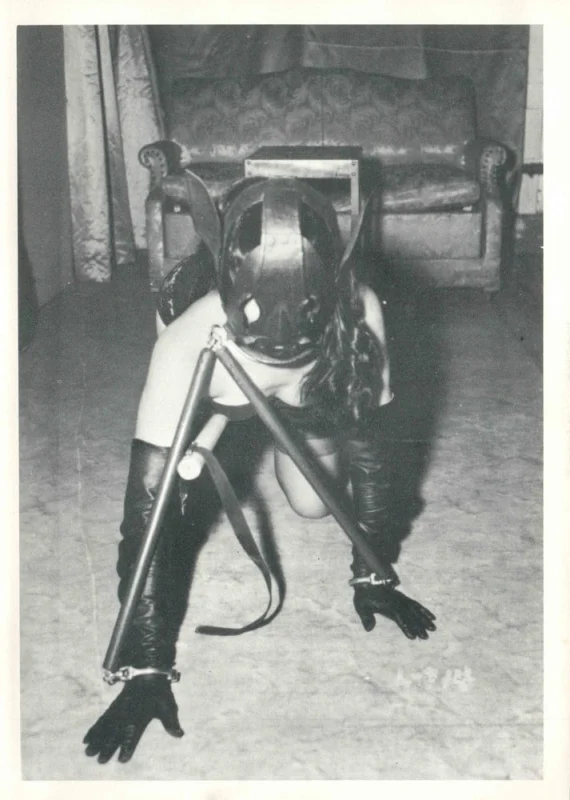

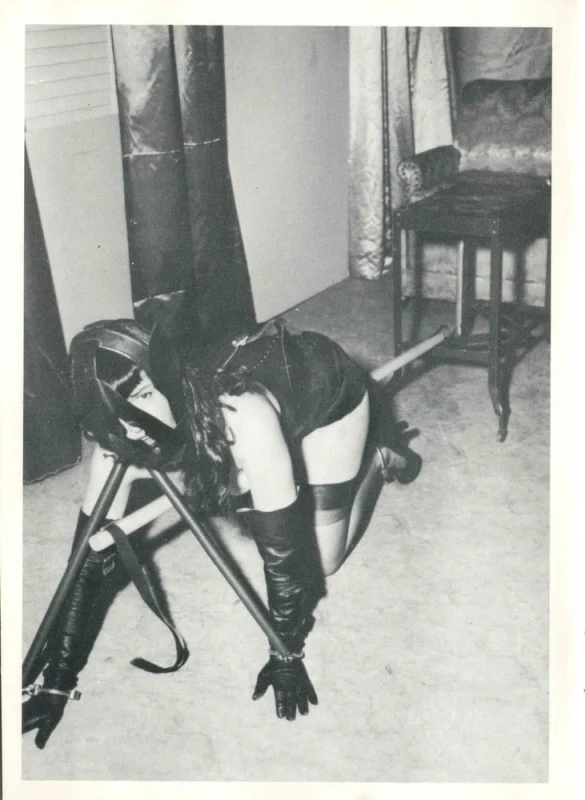

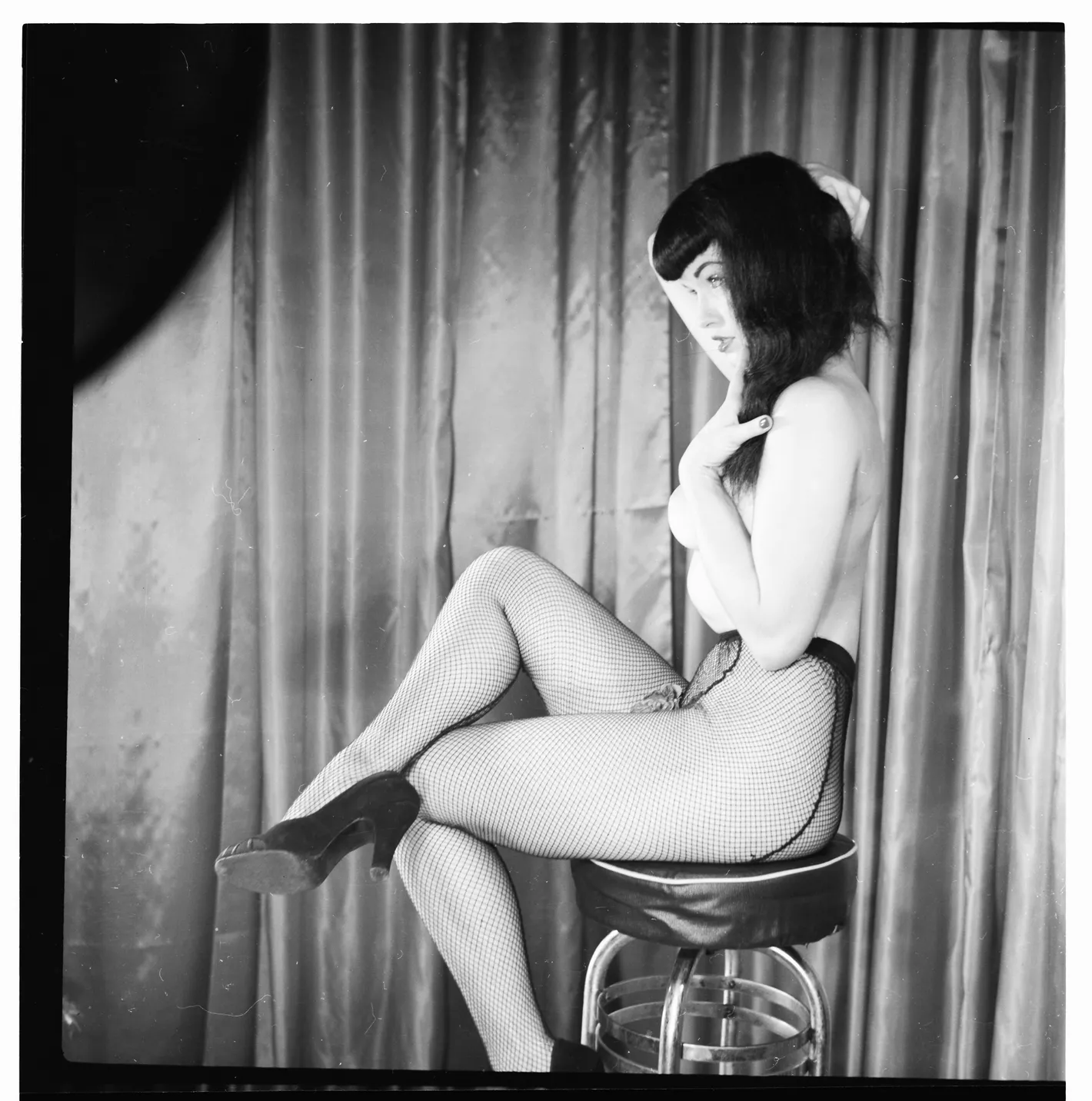

From late 1951 or early 1952 through 1957, Page began working regularly with photographer Irving Klaw. Klaw specialised in pin up and BDSM themed material sold through discreet mail order catalogues. Through this work, Page became the first famous bondage model in American popular culture.

Klaw also produced short black and white 8mm and 16mm films, silent one reel featurettes designed to fulfil very specific client requests. These films showed women in lingerie and high heels acting out scenes of abduction, domination and slave training. Bondage, spanking, elaborate leather costumes and restraints featured periodically. Page alternated between playing a stern dominatrix and a helpless victim bound hand and foot.

Despite later assumptions, these films never contained nudity or explicit sexual acts. They occupied the same underground world as stag films, but were carefully controlled. Klaw also sold still photographs taken during these sessions. One image in particular, showing Page gagged and bound in a web of rope from the film Leopard Bikini Bound, became his highest selling photograph and one of the most recognisable fetish images of the twentieth century.

Page was always clear about her reasons for participating. Reflecting later on the reputation these images gave her, she said:

“They keep referring to me in the magazines and newspapers and everywhere else as the Queen of Bondage. The only bondage posing I ever did was for Irving Klaw and his sister Paula. Usually every other Saturday he had a session for four or five hours with four or five models and a couple of extra photographers, and in order to get paid you had to do an hour of bondage. And that was the only reason I did it.”

She insisted that the work carried no personal meaning for her. “I never had any inkling along that line. I don’t really disapprove of it. I think you can do your own thing as long as you’re not hurting anybody else. That’s been my philosophy ever since I was a little girl.”

She also noted how ordinary the clients often were. “We used to laugh at some of the requests that came through the mail, even from judges and lawyers and doctors and people in high positions. Even back in the 50s they went in for the whips and the ties and everything else.”

Acting, Burlesque and Respectability

Page never limited herself to Klaw’s studio. In 1953 she enrolled at the Herbert Berghof Studio to study acting. This led to appearances on television programmes such as The United States Steel Hour and The Jackie Gleason Show. She also performed in Off Broadway productions including Time Is a Thief and Sunday Costs Five Pesos.

Her film career consisted mainly of burlesque revue features. She appeared in Striporama, directed by Jerald Intrator, followed by Teaserama and Varietease, both produced by Klaw. These films featured Page alongside well known striptease artists Lili St Cyr and Tempest Storm. They were mildly risqué but avoided nudity or overt sexual content.

Throughout her career, Page drew firm lines. Although she posed nude, she never appeared in explicit sexual scenes. This distinction mattered deeply to her, even as it was blurred by public imagination.

Florida and the Birth of Jungle Bettie

In 1954, during one of her regular trips to Florida, Page met photographer Bunny Yeager, a former model with a keen eye for natural settings and female autonomy. Yeager signed Page for a shoot at Africa U S A, a now closed wildlife park in Boca Raton.

The resulting Jungle Bettie photographs became some of the most celebrated images of Page’s career. They included nude shots of Page posing with cheetahs named Mojah and Mbili, as well as photographs of her wearing a leopard skin patterned jungle girl outfit that she made herself. Page also crafted much of her own lingerie.

These images felt playful and self possessed rather than staged or submissive. Yeager later sent the photographs to Playboy founder Hugh Hefner, who selected one for the January 1955 Playmate of the Month centre fold. The image showed Page kneeling before a Christmas tree wearing only a Santa hat, holding an ornament and winking directly at the camera.

In 1955, Page was named Miss Pinup Girl of the World. She also became known as the Queen of Curves and the Dark Angel. Unlike most pin up models, whose careers were brief, Page remained in high demand until 1957.

Moral Panic and the Kefauver Hearings

Between 1949 and 1957, an estimated 20,000 mail order bondage photographs of Page were produced. This underground popularity eventually attracted the attention of Senator Estes Kefauver, who launched hearings into juvenile delinquency and the impact of pornography on American youth.

Klaw was subpoenaed on 19th May, 1955. During the hearings, Florida man Clarence Grimm testified that his son Kenneth’s suicide had been inspired by bondage imagery featuring Page. Special counsel Vincent Gaughan guided Grimm to confirm that the position in which his son was found was directly influenced by Klaw’s photographs.

Although Page herself was spared from testifying, the implication that her work had contributed to a teenager’s death horrified her. Klaw collaborator Eric Stanton later recalled that it was “the only time I ever saw Bettie upset. She was horrified at the prospect of having to testify against her friends.”

The hearings destroyed Klaw’s business and effectively ended Page’s modelling career in New York. Shortly afterwards, she left the city for good.

In 1957, Page gave expert guidance to the FBI regarding the production of bondage and flagellation pictures in Harlem, an unusual coda to her involvement in the world that had both elevated and damaged her.

Conversion and Withdrawal

By the end of the 1950s, Page disappeared almost entirely from public view. On New Year’s Eve, 1958, while visiting Key West, she attended a service at what is now the Key West Temple Baptist Church. She was drawn to its multiracial congregation and soon became a born again Christian.

“When I gave my life to the Lord,” she later said, “I began to think he disapproved of all those nude pictures of me.”

She married Armond Walterson on 6th November, 1958. The marriage ended in divorce on 10th October, 1963. She briefly remarried her first husband Billy Neal, but the marriage was soon annulled. During the 1960s, she attempted to become a Christian missionary in Africa but was rejected because she was divorced.

She worked for various Christian organisations and spent time employed full time by Rev Billy Graham. She enrolled at Peabody College to pursue a master’s degree in education, but eventually dropped out.

Mental Illness and Institutional Life

In 1966, Page married Harry Lear. By the early 1970s, her mental health deteriorated dramatically. In January 1972, she ran through a Boca Raton ministry retreat carrying a pistol. Later that year, she forced her husband and his children at knife point to pray.

She was hospitalised and later voluntarily recommitted under suicide watch. In October 1978, she moved to Southern California to be closer to her brother. Shortly afterwards, she suffered a nervous breakdown following an altercation with her landlady.

Doctors diagnosed her with acute schizophrenia, and she was committed to Patton State Hospital in San Bernardino for 20 months. In April 1982, after another violent incident with a landlord, she was found not guilty by reason of insanity and placed under state supervision for eight years. She was released in 1992.

Rediscovery Without Consent

While Page lived quietly in group homes and hospitals, her image underwent a dramatic revival. From the late 1970s onwards, artists such as Olivia De Berardinis and Robert Blue began painting her. Comic book artist Dave Stevens based the character Betty in The Rocketeer on her likeness.

By the mid 1980s, women began appearing at gallery openings wearing Bettie bangs, seamed stockings and stilettos. De Berardinis later observed, “Although the fantasy world of fetish existed in some form since the beginning of time, Bettie is the iconic figurehead of it all. No star of this genre existed before her.”

Page was unaware of any of this. In a 1993 telephone interview, she told Robin Leach she was “penniless and infamous”. Her brother Jack eventually contacted her and explained that books, calendars and merchandise bearing her face were being sold worldwide.

She began reclaiming control over her image, signing with Curtis Management Group and occasionally autographing photographs. In interviews, she was pragmatic about her past. “I never thought it was shameful,” she said in 1998. “It’s just that it was much better than pounding a typewriter eight hours a day.”

Death and Legacy

Bettie Page was hospitalised in critical condition on 6th December, 2008, suffering from a heart attack and pneumonia. Her family agreed to discontinue life support, and she died on 11th December, 2008, aged 85.

In the years since her death, her estate has earned millions. In 2011 and again in 2014, Forbes listed her among the top-earning dead celebrities, earning $6 million and tied with the estates of George Harrison and Andy Warhol, at 13th on the list. In 2014, Forbes estimated that Page's estate earned $10 million in 2013. In 2023, a historical marker commemorating her life was erected in Nashville.

Bettie Page remains a paradox. A woman who became a symbol of erotic liberation while seeking personal restraint. A cultural icon who spent decades in obscurity. Her image endures, but her life tells a far more complex story about agency, morality and the cost of being seen.