Polaroids From Return of the Jedi and the Careful Art of Ending a Modern Myth

- Jan 1

- 7 min read

In the early 1980s, few filmmakers faced a stranger problem than Return of the Jedi. The first Star Wars film had exploded into popular culture almost by accident. Its sequel, The Empire Strikes Back, had deepened that universe, darkened its tone, and proved that a blockbuster could carry genuine emotional weight. By the time work began on the third chapter, Star Wars was no longer a gamble. It was a cultural force, a merchandising empire, and a shared language.

What remained uncertain was how to end it.

Released in 1983, Return of the Jedi was tasked with doing several things at once. It needed to resolve a generational story about fathers and sons. It had to deliver spectacle on a scale audiences now expected. It had to satisfy children, teenagers, and adults who had grown up rapidly in the six years since the original film. And it had to do all of this without collapsing under its own commercial success.

The result was a film that often feels warmer, more playful, and more openly mythic than its immediate predecessor. It is also a film shaped by compromise, intense behind the scenes debate, and a director navigating one of the most closely watched productions in cinema history.

After Empire success and a swift return to production

Following the commercial and critical success of The Empire Strikes Back, Lucasfilm moved quickly. A third Star Wars film was always part of the plan, but Empire’s box office performance removed any lingering hesitation. George Lucas once again chose to finance the film himself, maintaining the independence that had defined the series since 1977.

This time, however, Lucas did not want to direct. He had found the experience of directing the first Star Wars exhausting, and Empire had demonstrated that another filmmaker could bring something valuable to the universe. Irvin Kershner, who directed Empire, declined to return. Lucas then approached Steven Spielberg, his close friend and creative ally. Both men, however, were in conflict with the Directors Guild of America, and Spielberg was effectively barred from directing the film.

Other names were considered. David Lynch, fresh from an Academy Award nomination for The Elephant Man, met with Lucas but declined. Lynch later explained that he felt Star Wars belonged to Lucas and should be directed by its creator. David Cronenberg also turned down the opportunity, preferring to work on projects he had written himself. Lucas briefly considered Lamont Johnson before finally selecting Richard Marquand.

Marquand was talented, thoughtful, and comparatively inexperienced with effects heavy productions. Lucas remained heavily involved on set as a result. Marquand later joked that directing the film felt like “trying to direct King Lear with Shakespeare in the next room”. Lucas, for his part, praised Marquand’s kindness and his ability to work patiently with actors under intense pressure.

Writing an ending while already in motion

The screenplay for Return of the Jedi was based on a story by Lucas and written with Lawrence Kasdan, who had also co written The Empire Strikes Back. From the outset, there were concerns about tone and even the title itself. Kasdan reportedly felt that Return of the Jedi sounded weak. Producer Howard Kazanjian agreed, and the title was briefly changed to Revenge of the Jedi before Lucas reconsidered. In his view, revenge was not the way of the Jedi.

Unusually, the screenplay was not finished until late in pre production. The production schedule and budget were already in place, and Marquand had been hired before a shooting script existed. Early work relied on Lucas’s story outlines and rough drafts. When the time came to finalise the script, Lucas, Kasdan, Marquand, and Kazanjian spent two intensive weeks in conference. Kasdan used transcripts of these discussions to assemble the final screenplay.

This collaborative but compressed process shaped the film’s structure. Certain ideas remained fluid until very late, and others were abandoned entirely. The tension between mythic closure and commercial expectation was present in almost every creative decision.

Would Han Solo return at all

One of the biggest uncertainties during pre production was whether Harrison Ford would return as Han Solo. Unlike Mark Hamill and Carrie Fisher, Ford had not been contracted for multiple sequels. His rising star after Raiders of the Lost Ark only complicated matters.

Kazanjian later said that Han’s freezing in carbonite in Empire was partly a practical decision. The filmmakers were unsure if the character would return at all. Early versions of the script reportedly excluded Han entirely. Ultimately, Kazanjian, who had also produced Raiders, persuaded Ford to come back.

Even then, Ford felt strongly that Han should die through an act of self sacrifice. Kasdan agreed, arguing that a major death early in the third act would restore uncertainty and raise the stakes. Gary Kurtz, who had produced the first two films but was replaced for Jedi, later claimed that Han did die in an early draft. Kurtz suggested that concerns about merchandising influenced Lucas’s decision to keep the character alive.

Kurtz also described a far bleaker ending. In that version, the Rebel forces were left in disarray, Leia struggled with her new responsibilities as a leader, and Luke walked away alone, “like Clint Eastwood in the spaghetti Westerns”. The version audiences received was more openly celebratory, but the shadow of these darker alternatives still lingers in the film’s structure.

Yoda, Ewoks, and the shape of a myth

One of the most debated creative choices involved the Ewoks. Early in development, Lucas considered making the forest dwellers Wookiees. The idea was abandoned when it became clear that Chewbacca’s people were meant to be technologically sophisticated. The Ewoks were smaller, more primitive, and closer to fairy tale creatures.

Yoda, meanwhile, was not originally meant to appear. Marquand argued strongly that audiences would expect a return to Dagobah. After consulting a child psychologist, Lucas became concerned that younger viewers might believe Darth Vader had lied about being Luke’s father in Empire. As a result, the scene in which Yoda confirms the truth was added.

Other ideas came and went. At one point, the Millennium Falcon was meant to land on Endor. Another version of the ending featured Obi Wan, Yoda, and Anakin Skywalker returning fully from their spectral existence in the Force. These revisions reveal a film constantly balancing clarity, myth, and audience expectation.

Casting new faces and reshaping old ones

New cast members included Ian McDiarmid as the Emperor and Warwick Davis as Wicket the Ewok. The role of the Emperor had initially been offered to Alan Webb, who withdrew due to illness. Other actors considered included Ben Kingsley and David Suchet.

McDiarmid’s performance brought a theatrical relish to the role, blending classical villainy with a modern sense of menace. Lucas and Marquand wanted the Emperor to feel ancient, manipulative, and amused by cruelty rather than physically imposing.

Kenny Baker was initially cast as Wicket, but illness on the day of filming led to his replacement by Davis, who had no previous film acting experience. Davis’s performance became one of the film’s most enduring contributions, grounding the Ewoks with a sense of personality rather than novelty.

Filming across deserts and forests

Principal photography began on 11th of January, 1982 and ran until the 20th of May 1982, a shorter schedule than Empire. Lucas was determined not to exceed the budget, which stood at approximately 32.5 million dollars. Kazanjian pushed for an early shoot to maximise the time available for Industrial Light & Magic.

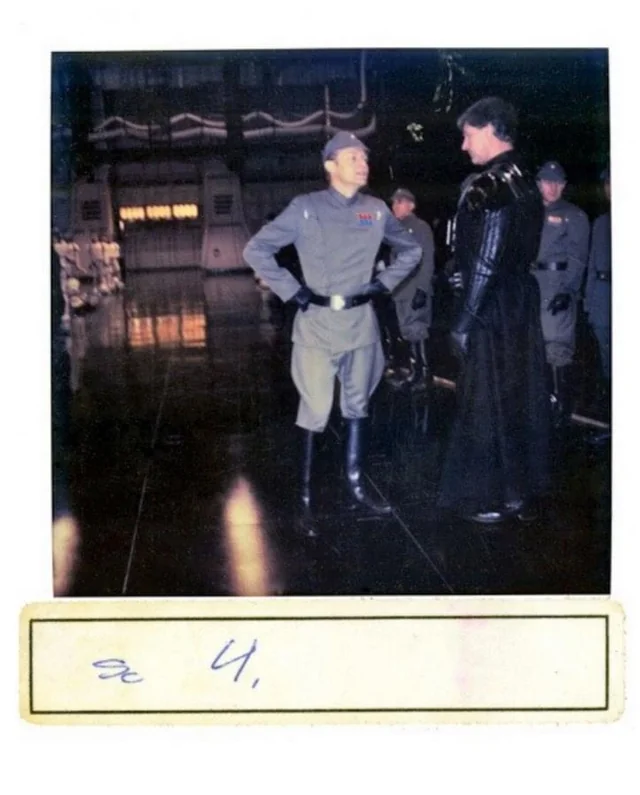

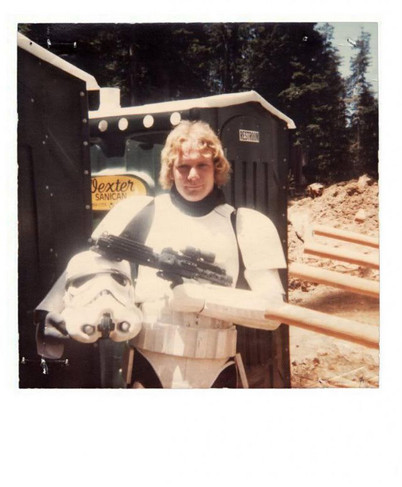

The production operated under the working title Blue Harvest, with the deliberately misleading tagline “Horror Beyond Imagination”. This was designed to deter fans and prevent service providers from inflating prices.

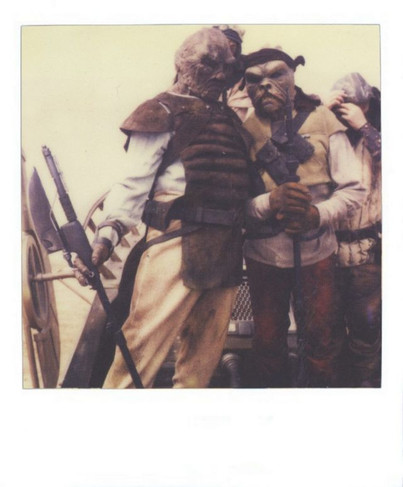

The film occupied all nine sound stages at Elstree Studios in England for 78 days. The first scene shot was later cut, involving a sandstorm escape from Tatooine. The Rancor presented its own challenges. Lucas initially wanted a performer in a suit, inspired by Japanese monster films, but technical limitations led to the creature being realised as a puppet filmed at high speed.

Location shooting took the crew to the Yuma Desert in Arizona for Tatooine exteriors, then to northern California. The Endor forest scenes were filmed in Grizzly Creek Redwoods State Park near Smith River. Bluescreen work followed at ILM in San Rafael, with additional matte plates shot in Death Valley.

The speeder bike chase was filmed using Steadicam by its inventor Garrett Brown, walking slowly while filming at less than one frame per second. When projected at normal speed, the footage conveyed extraordinary velocity. Vader’s funeral scene was filmed at Skywalker Ranch.

Not all on set relationships were smooth. Marquand clashed with Anthony Daniels, leading Daniels to record dialogue directly with Lucas. Fisher reportedly found Marquand’s directing style stressful, and one confrontation ended with her in tears, halting production while her makeup was reapplied.

Sound, spectacle, and the birth of THX

During test screenings, Lucasfilm encountered an unexpected problem. Sound mixes that worked perfectly in studio conditions failed in commercial cinemas. Effects were inaudible, dialogue was muffled, and background noise overwhelmed key moments. Many theatres were poorly equipped, relying on mono sound systems and inadequate acoustics.

Lucas’s solution was not to compromise but to build something new. The experience directly led to the creation of THX, a company designed to standardise and improve cinema sound. Every theatre showing Lucasfilm productions would now meet a specific technical standard.

Meanwhile, ILM was operating at full capacity. The company produced approximately 900 effects shots for the film, often working 20 hour days, six days a week. The aim was to surpass both previous films visually, even as staff shortages and external commitments stretched resources to the limit.

Ending Star Wars without closing it

Return of the Jedi premiered in 1983 and was received as a satisfying, if safer, conclusion to the trilogy. Its emphasis on redemption, particularly in the relationship between Luke and Vader, reaffirmed Lucas’s interest in myth rather than cynicism. The film’s brighter tone, its fairy tale elements, and its celebration of community stood in contrast to Empire’s unresolved darkness.

In retrospect, Return of the Jedi feels less like an ending and more like a pause. It closed one story while leaving the universe intact. That may be its greatest achievement. It understood that Star Wars had become something larger than any single film, and that its true power lay in inviting audiences to imagine what came next.