How a Victorian Doctor Called Gustaf Zander Invented the Modern Gym

- Dec 19, 2025

- 6 min read

At some point in the early weeks of January, amid abandoned fitness apps and the quiet repurposing of home gym equipment into coat racks or doorstops, a familiar question tends to surface. When did exercise stop being a personal habit and become an organised industry? The answer does not begin with neon lit gyms, protein shakers, or celebrity trainers. It begins, more quietly and more methodically, in nineteenth century Stockholm, inside a room filled with machines designed not for spectacle but for prescription.

Long before the modern fitness industry took shape, a Swedish physician named Gustaf Zander was already laying its foundations. Born on the 18th of October 1835, Zander did not set out to create a culture of self improvement or aesthetic transformation. His ambition was narrower and, in many ways, more radical. He wanted to treat the human body with the same systematic precision that industrial society was beginning to apply to machines.

This is the story of how Zander’s medico mechanical system helped shape modern gym culture, how exercise became medicalised, and why the modern workout cannot be separated from the history of work, class, and mechanisation.

Exercise before gyms

Organised physical training long predates the modern gym. Ancient Greek gymnasia were central to civic life, combining athletic training with philosophy and education. In Indigenous North America, the Haudenosaunee Confederacy trained endurance, agility, and coordination through games such as lacrosse, long before the sport was codified by European settlers. Across history, empires, religions, and states have promoted physical regimens for military readiness, moral discipline, or spiritual purification.

What these systems generally shared was an emphasis on effort, repetition, and communal discipline. Exercise was visible, social, and often competitive. Zander’s contribution was something altogether different. He removed physical training from the field, the drill hall, and the schoolyard, and placed it instead in the clinic. Exercise became individualised, mechanised, and supervised by medical authority.

A medical mind in an industrial age

At the time of Zander’s birth in 1835, Sweden was undergoing significant social change. Industrialisation was beginning to reshape daily life, particularly in cities such as Stockholm. Traditional forms of labour that demanded sustained physical effort were slowly giving way to clerical work, factory supervision, and administration. Physicians and social reformers increasingly worried that modern bodies were becoming weak, stiff, and prone to chronic pain.

Zander trained as a physician at the Karolinska Institute, one of Europe’s leading medical schools. From early in his career, he showed an unusual interest in movement itself, not as recreation or moral instruction, but as a physiological process that could be measured, controlled, and improved. Gymnastics had long been used in schools and the military, often tied to nationalism or character building. Zander approached it clinically. Exercise, in his view, was something to be prescribed.

The birth of medico mechanical gymnastics

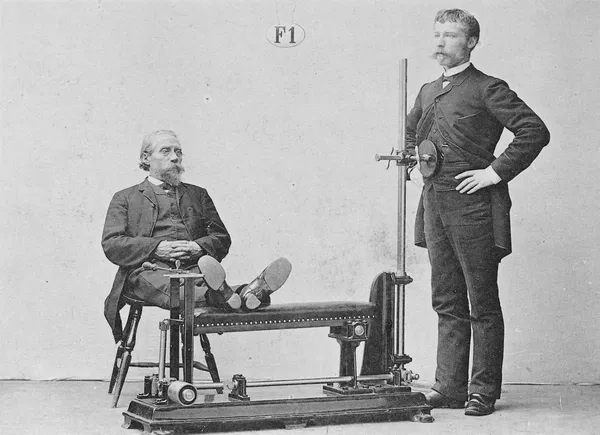

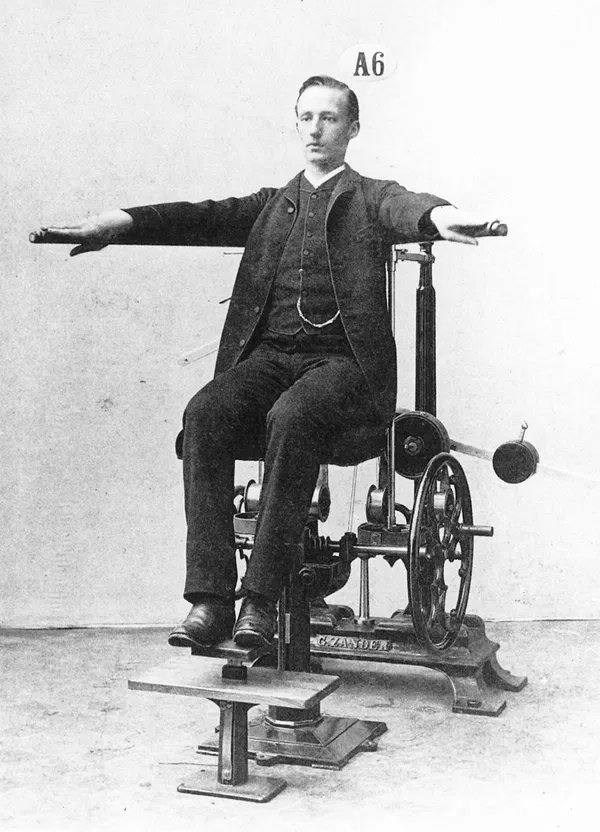

In 1865, Zander opened his first Mechanico Therapeutic Institute in Stockholm. It contained just twenty seven machines, many designed and refined by Zander himself. Each apparatus targeted a specific muscle group or joint, guiding the body through controlled movements while limiting strain. The machines were intended not for athletes, but for patients suffering from back pain, joint stiffness, poor posture, and the vague complaints associated with sedentary office work.

Zander described his system in explicitly medical terms. In his 1894 treatise on medico mechanical gymnastics, he explained that exercise should be administered much like a drug. “The prescription of exercise is methodically composed according to the needs and condition of the patient,” he wrote. Sessions were supervised, movements timed, and resistance carefully adjusted. There was little room for improvisation or competition.

The approach worked. As Swedish writer Sven Lindqvist later recorded, Zander’s system expanded rapidly. By 1877, just twelve years after the opening of the first institute, there were fifty three different Zander machines operating in five Swedish towns. Clinics appeared not only in Stockholm but also in Gothenburg and Malmö, serving clerks, civil servants, and middle class patients whose ailments reflected the pressures of modern office life.

From welfare medicine to international export

Initially, Zander’s work aligned closely with Sweden’s emerging welfare state. His research was government funded, and his institutes were accessible to a wide public. Exercise was framed as preventative medicine, a way to reduce long term illness and maintain a productive workforce.

That changed after 1876. In that year, Zander exhibited his machines at the Centennial International Exhibition in Philadelphia. The exhibition attracted millions of visitors and showcased industrial and scientific achievements from around the world. Zander’s machines won a design award and drew the attention of physicians, spa owners, and entrepreneurs.

After Philadelphia, Zander repositioned himself. While he continued to speak the language of medicine, his machines increasingly found homes in private clinics, luxury health resorts, and elite institutions. By the 1880s and 1890s, Zander equipment was being exported to Russia, England, Germany, and Argentina. He stepped away from his academic post at the Karolinska Institute and became an international fitness entrepreneur.

Work, bodies, and machines

The rise of the Zander system cannot be separated from wider anxieties about work in the late nineteenth century. Industrialisation had transformed not only labour but bodily experience. Prolonged sitting, repetitive motions, and mental strain produced new categories of illness. Doctors debated “office sickness”, nervous exhaustion, and muscular imbalance.

Zander marketed his machines as protection against “a sedentary life and the seclusion of the office”, promising “increased well being and capacity for work”. There was an irony at the heart of this claim. The same machines that reduced physical exertion at work now required people to seek artificial exertion elsewhere. One set of machines weakened the body through inactivity, another repaired it through controlled motion.

In this sense, the modern workout emerged not from leisure but from labour. Exercise became a compensatory activity, a way of maintaining bodily function in an economy that no longer required physical strength.

Passive fitness and the illusion of effort

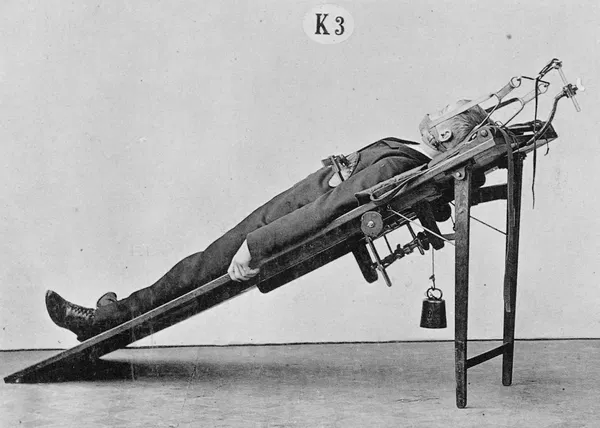

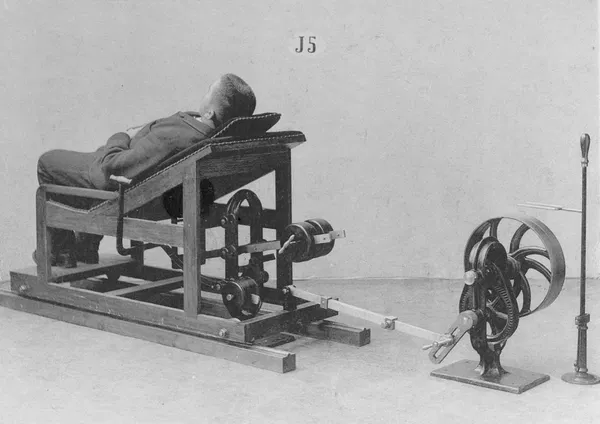

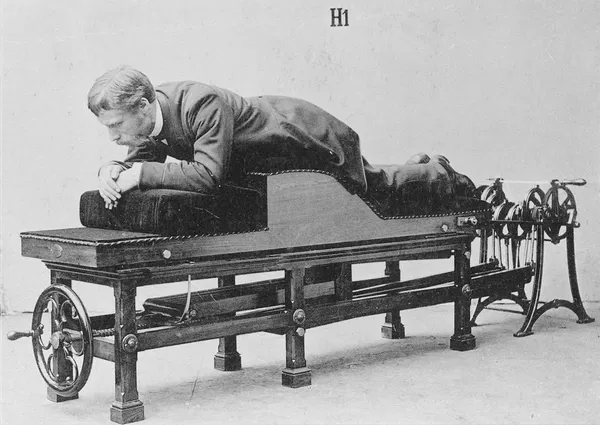

Perhaps the most surprising aspect of Zander’s system was its emphasis on passivity. Unlike modern strength training, which celebrates effort, sweat, and personal struggle, Zander’s machines were designed to minimise exertion. Many were powered by external energy sources, including steam, gasoline, and electricity. The patient’s task was simply to be positioned correctly while the machine moved their limbs.

Zander believed excessive effort risked injury and reduced therapeutic value. By controlling speed, resistance, and range of motion, his machines promised improvement without fatigue. Patients were reassured that the work was being done for them.

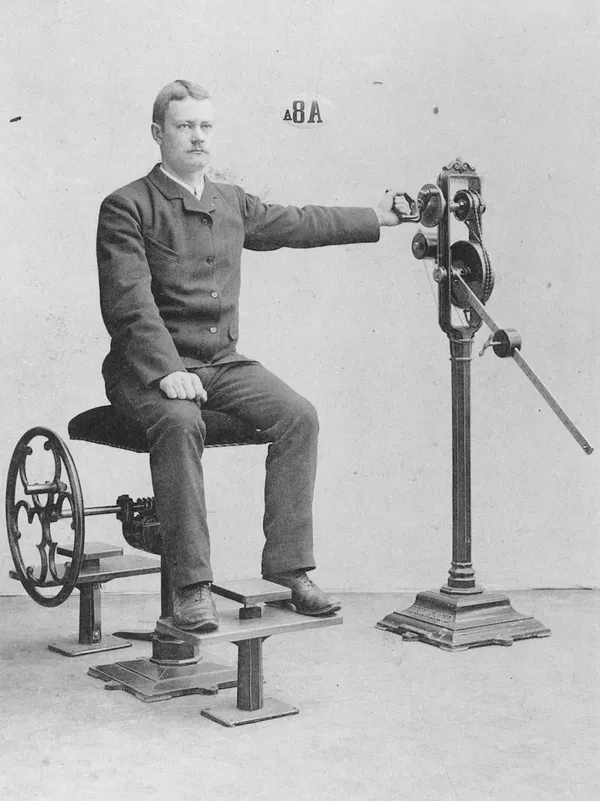

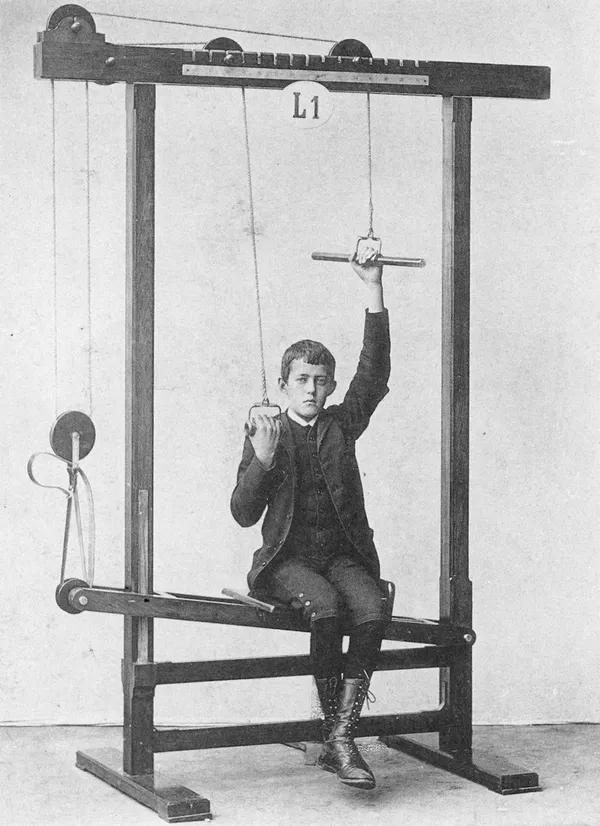

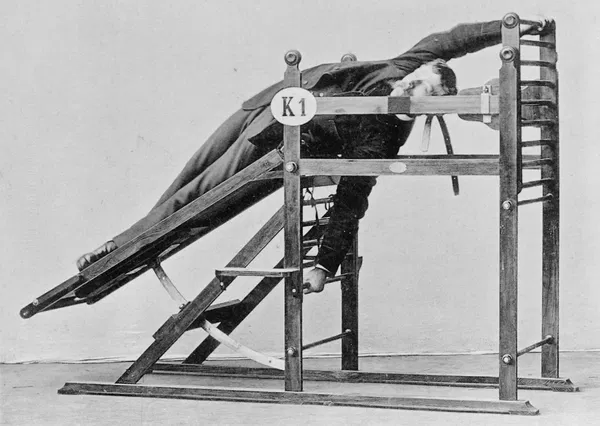

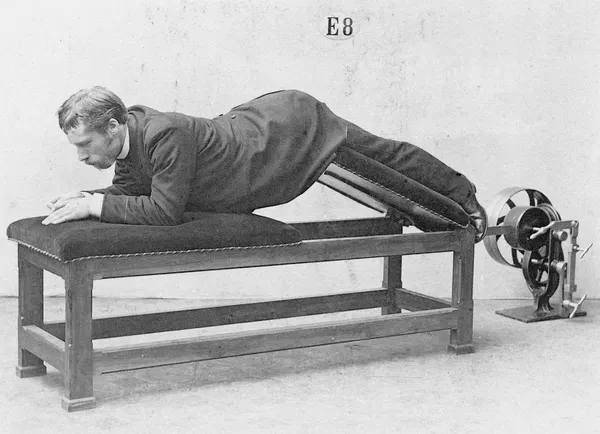

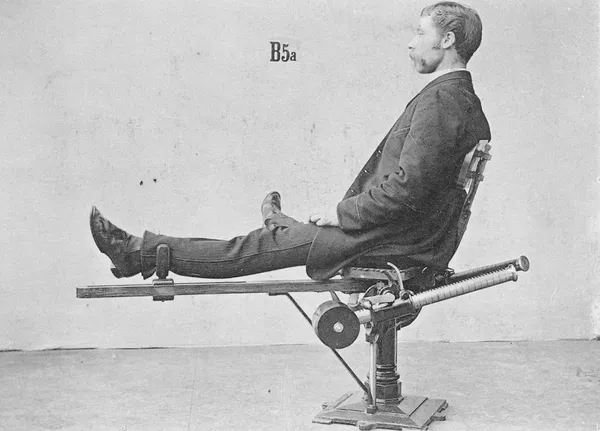

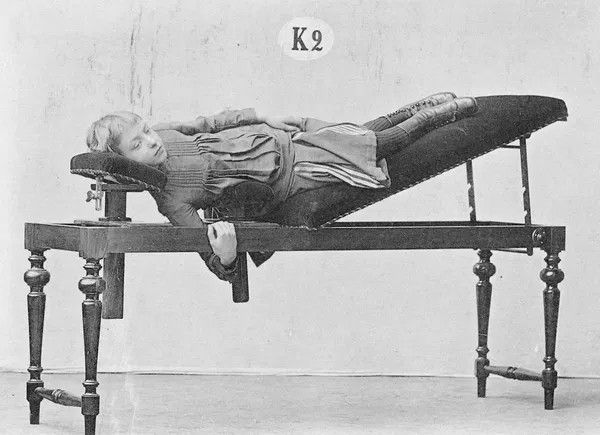

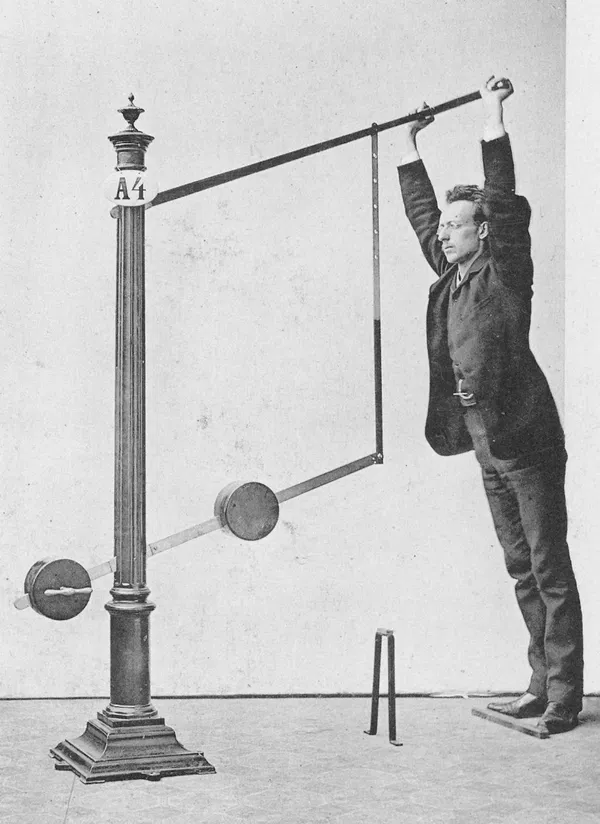

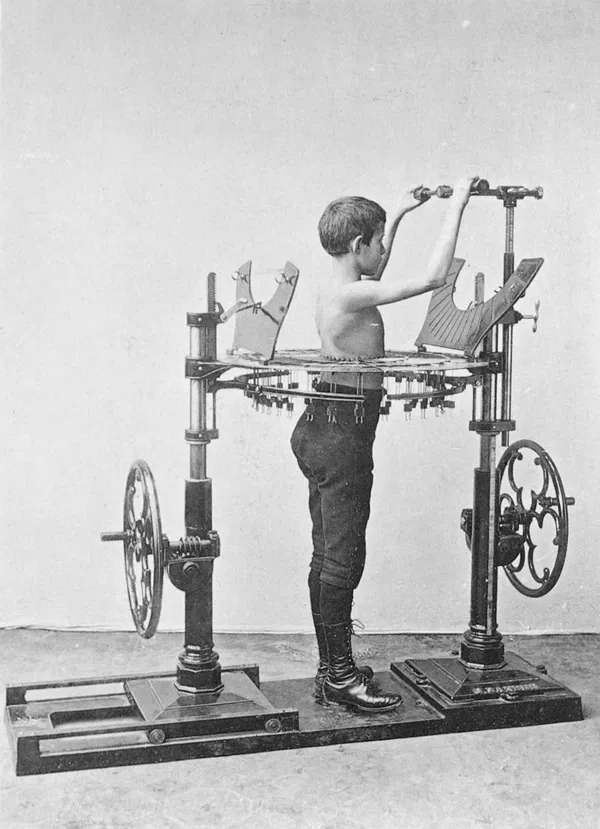

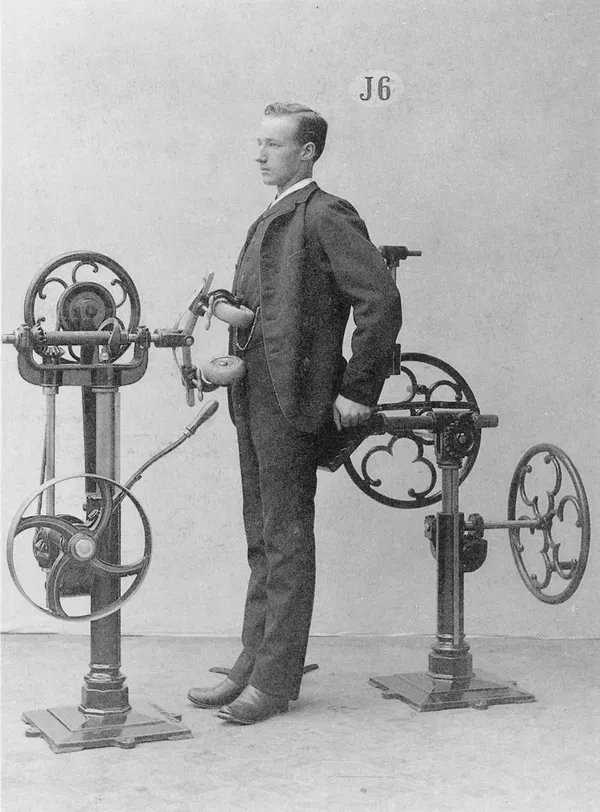

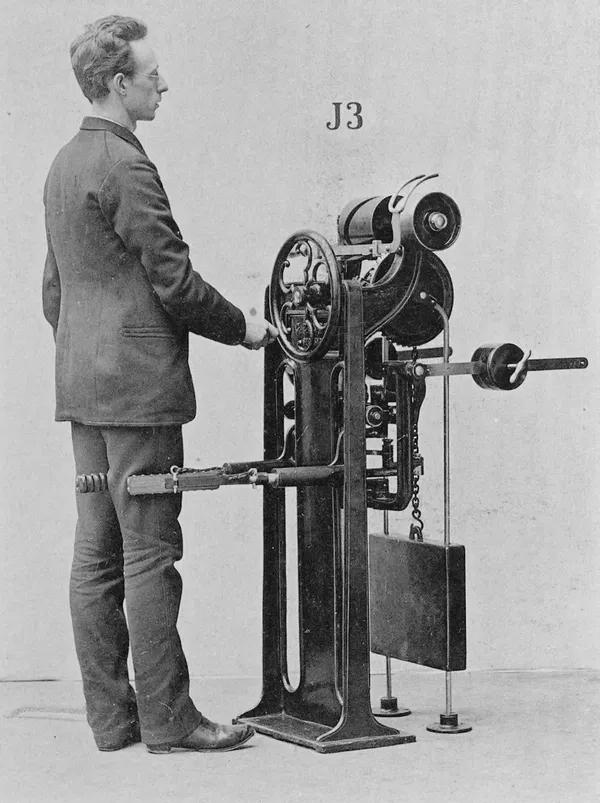

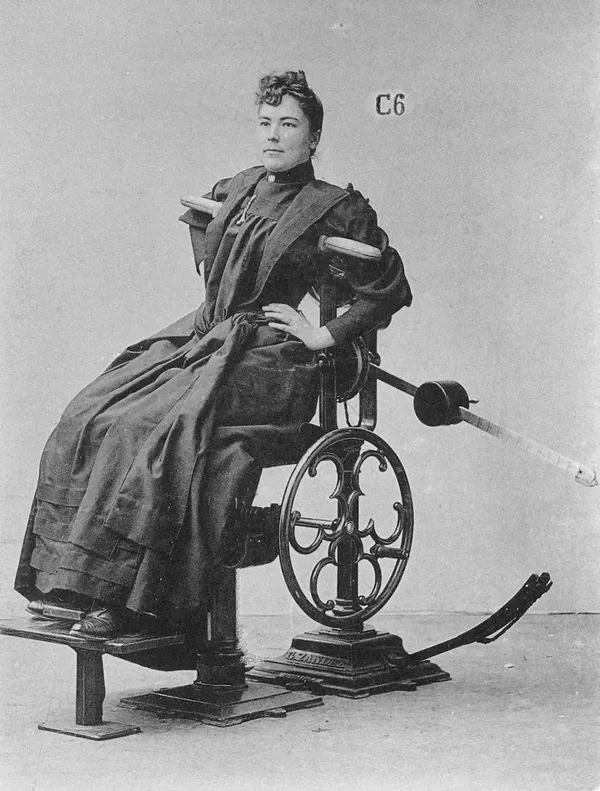

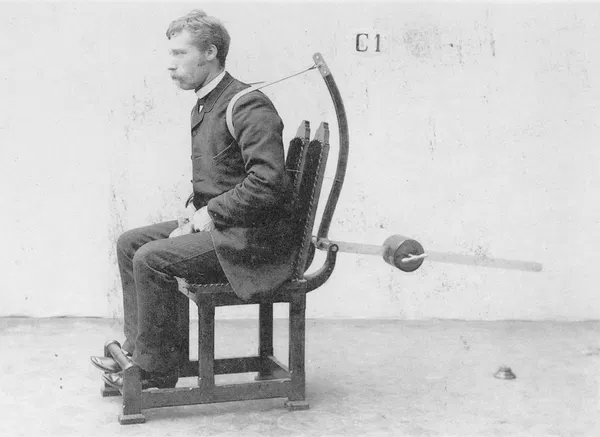

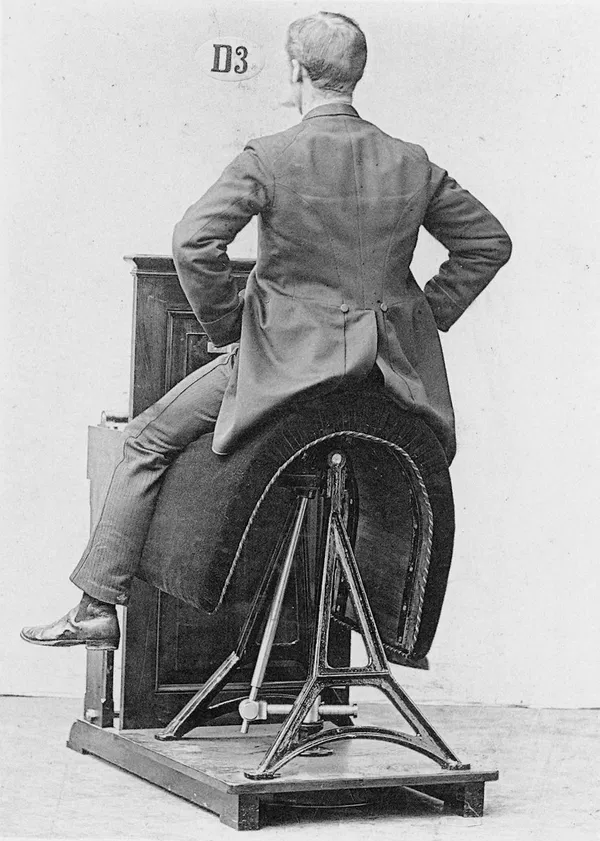

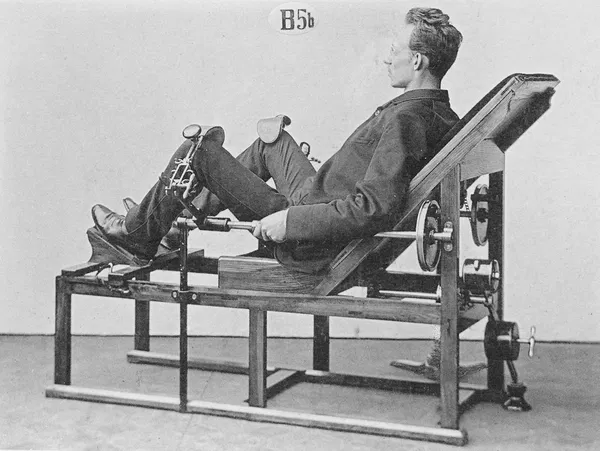

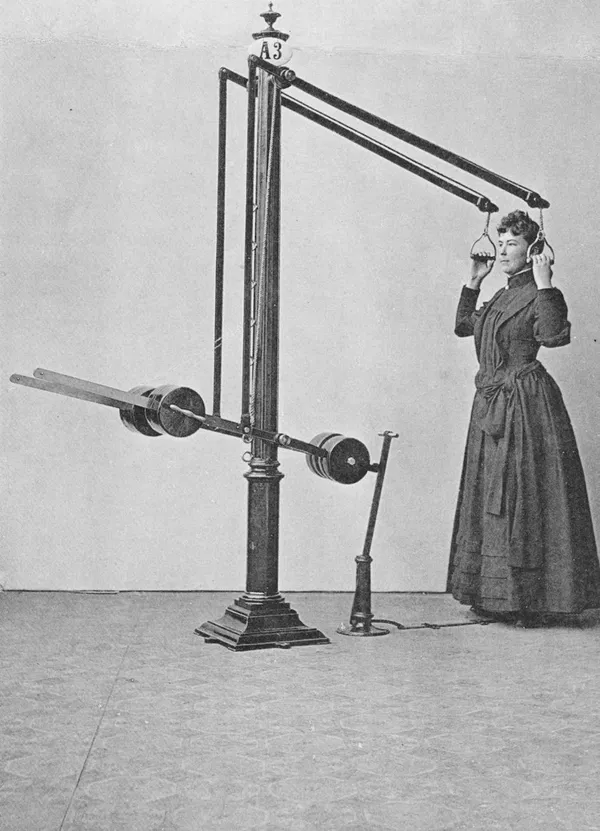

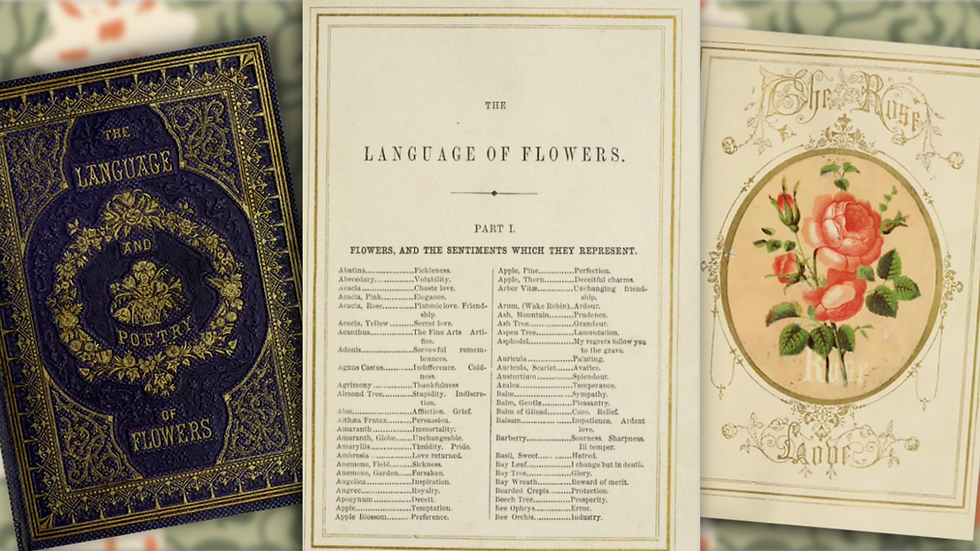

Photographs and illustrations from catalogues produced by Görransson’s mekaniska verkstad, later reproduced in Dr Alfred Levertin’s 1892 book on Zander’s system, show men and women dressed in formal clothing calmly engaging with elaborate apparatus. Faces are composed. Bodies appear relaxed. There is little visible strain.

To modern eyes, these scenes feel uncanny. Contemporary fitness culture thrives on competition, metrics, and visible exertion. Zander’s system offered the opposite. Health without heroics.

Fitness, class, and control

Historian Carolyn Thomas, formerly Carolyn de la Peña, has argued that Zander’s later success reflected shifting ideas about class and bodily authority. In mechanised workouts, white collar professionals cultivated a new form of power. Fitness came to be defined not by the ability to perform physical labour, but by the possession of a balanced, symmetrical physique.

This redefinition mattered. It detached physical strength from productive labour and attached it instead to leisure and consumption. The endurance of factory workers no longer counted as fitness. Controlled exercise in private spaces became the new ideal. As Thomas writes, body power shifted from labourers to loungers.

Zander’s machines translated the discipline of the factory into the clinic. Order, regularity, and control were applied to the body itself.

The legacy of Gustaf Zander

Gustaf Zander died on 15 March 1920. By then, his machines could be found in hospitals, sanatoria, and private clubs across Europe and beyond. Although many of his original devices were eventually replaced, the principles behind them endured.

Modern resistance machines, with guided movements and adjustable loads, owe a clear debt to Zander’s designs. So too does the idea that exercise should target specific muscle groups, be standardised, and be prescribed. Even the language of today’s fitness industry echoes the clinical tone of Zander’s writing.

Yet Zander’s vision was never about transformation or conquest. It was about maintenance, balance, and preventing decline. In an age obsessed with optimisation, that restraint feels almost radical.

The next time a forgotten kettlebell props open a door, it is worth remembering that the modern workout began not as a test of willpower, but as a medical intervention, devised by a Victorian doctor who believed machines could quietly teach bodies how to move again.

Comments