The Language of Flowers: A Victorian Secret

- Harriet Wilder

- Aug 4, 2025

- 4 min read

Updated: Aug 14, 2025

“Say it with flowers,” they said — and in Victorian Britain, they meant it quite literally.

In an age where open displays of emotion were often considered improper, especially for women and the upper classes, a unique form of communication quietly blossomed: the language of flowers. It was a secret code of petals and stems, thorns and leaves, one that allowed people to speak volumes without ever saying a word.

Whether it was love, grief, rejection, hope, or even shame, every sentiment had its floral symbol. Bouquets became missives. A single flower, placed deliberately and perhaps turned upside-down, could carry a message more complex than a page of prose. This wasn’t just poetic fancy; it was a whole system of meaning, recorded, printed, and studied in books like An Alphabet of Floral Emblems, one of the most exquisite and comprehensive guides of its time.

Feelings in Full Bloom

Victorian society was, on the surface, one of restraint. Emotion was tucked beneath corsets and behind stiff collars. But that didn’t mean people didn’t feel deeply. They just needed a socially acceptable outlet. Flowers, beautiful, symbolic, and already entwined with rituals of courtship and mourning, became that outlet.

In An Alphabet of Floral Emblems, each flower is paired with a specific feeling, message, or virtue. Some meanings still resonate today. A red rose, unsurprisingly, stood for love. But the details matter: a deep red rose? That meant bashful shame. A pink carnation expressed admiration, while a white one hinted at a broken heart. A gum cistus, a wild-looking flower also known as the rockrose, carried the dramatic message: “I shall die to-morrow.” It was, in short, serious business.

This symbolic vocabulary allowed people to “say the unsayable.” Want to declare undying love but can’t speak it aloud? Send a posy of honeysuckle, ivy, and lilac. Need to rebuff a suitor? A yellow carnation would do the job — it stood for rejection.

A Dictionary of Petals

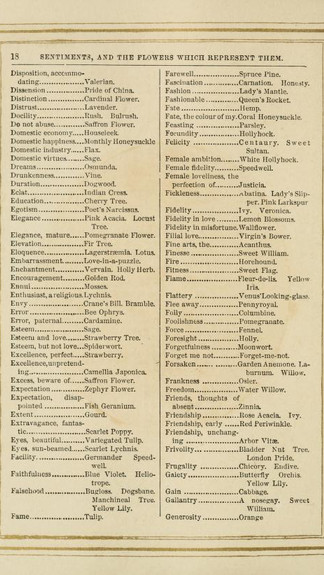

The book is more than a floral directory — it’s a double dictionary. First, you can look up a flower and find the emotion it’s said to represent. Then, you can search by sentiment and find the best floral messenger for your message.

Here are just a few pairings from the Alphabet of Floral Emblems:

Carnation – Fascination

Geranium – Gentility

Dahlia – Instability

Lily of the Valley – Return of Happiness

Yellow Jasmine – Grace and Elegance

Pansy – Thoughts

White Rose – Innocence and Silence

And then there are the more obscure ones:

Everlasting Pea – Lasting pleasure

Gum Rockrose – “I shall die to-morrow”

Bachelor’s Button – Hope in love

Barberry – Sourness of temper

Extracts from The Alphabet of Floral Emblems

It wasn’t just the flower itself that mattered. The way it was presented added extra nuance.

“If a flower be given reversed,” the book tells us, “it implies the opposite of that thought or sentiment which it is ordinarily understood to express.” “A rosebud from which the thorns have been removed, but which has still its leaves, conveys the sentiment, ‘I fear, but I hope,’—the thorns implying fear, as the leaves hope.” “Remove the leaves and thorns, and then it signifies that ‘There may be neither hope nor fear’; while again, a single flower may be made emblematical of a variety of ideas.”

Even the absence of parts, thorns stripped away, leaves plucked, changed everything. No florist’s arrangement was accidental. It was a letter in disguise.

When Poetry and Posies Collided

To deepen the emotional power of these floral codes, The Alphabet of Floral Emblems included poetry. Some verses were original, penned by lesser-known writers like Miss J. A. Fletcher or C. A. Fillebrown. Others were adapted from popular poems of the time. All served the same purpose: to evoke the mood behind the bloom.

These weren’t just decorative lines but heartfelt additions meant to give emotional weight to a gift of flowers. A sprig of forget-me-nots might come with a verse about memory and devotion. A violet might carry a melancholy stanza about modesty and loss. It was a deeply sentimental age — and the Victorians excelled at sentiment.

The Nosegay as Love Letter

We often think of Victorians as buttoned-up and unfeeling, but their interest in the “language of flowers” shows quite the opposite. What they lacked in emotional openness, they made up for in symbolism, ritual, and poetry. A walk through a Victorian garden could feel like entering a well-composed novel, where every plant whispered a secret. A bouquet wasn’t just a bouquet — it was a story, a confession, a warning, or a question.

“The nosegay might be made to take the place of more formal epistles,” the book’s author remarks — and indeed, many Victorians became fluent in this silent but deeply expressive language.

Next time you see a bunch of flowers, consider the meanings hidden in their petals. That daisy might be speaking of innocence. That camellia might be mourning a love lost. And that delicate, overlooked sprig of rosemary? It remembers.

You can view the PDF of the book in full below.

Further Reading

– The Alphabet of Floral Emblems, 1857 edition

– Green, F. L., Floriography: The Victorian Language of Flowers, 1893

– M. Kirkpatrick, The Language of Flowers: A History, 2014

Words by Harriet Wilder, Time-Travel Correspondent

Contributor, UtterlyInteresting.com — exploring the strange and forgotten corners of history.