Remembering Rabindranath Tagore on Baishe Srabon: "And Because I Love This Life, I Know I Shall Love Death As Well"

- Aug 7, 2020

- 6 min read

Updated: Aug 9, 2025

Every year on Baishe Srabon, the 22nd day of the Bengali month of Shravan, people across Bengal pause to remember a man whose words once shaped a nation and still stir hearts a century later. Rabindranath Tagore wasn’t just one of the great masters of literature, he was a once-in-a-generation phenomenon. Poet, philosopher, composer, educator, reformer, and artist, he helped shape modern Indian identity while bridging cultures and continents with his thought and verse.

Born in 1861 into the cultured and reformist Tagore family, young Rabindranath grew up in the Jorasanko mansion in Calcutta (now Kolkata). His father, Debendranath Tagore, was a religious reformer associated with the Brahmo Samaj, a movement that sought to modernise Hinduism. Immersed in music, literature and philosophy from an early age, Rabindranath began writing poetry as a child and published his first collection at just 16.

Though he briefly studied law in England in the late 1870s, he returned to India without a degree but with sharpened ideas about culture, society and learning. Over the next decades, he would redefine what it meant to write in Bengali. He introduced new prose and verse forms and made the language more accessible and lyrical by moving away from the rigid structures of classical Sanskrit. In doing so, he brought literature closer to everyday speech, and closer to the lives of the people.

Living Among the People He Wrote About

In 1891, Tagore left the bustle of Calcutta for East Bengal (now Bangladesh) to manage his family’s estates in Shilaidah and Shazadpur. Living in a houseboat on the Padma River, he came into close contact with the local villagers and their daily struggles. It was here that his sympathy for the poor and marginalised deepened, and it became a cornerstone of his later writing.

Some of his finest short stories emerged during this time. Written in the 1890s, they are often simple, quiet tales of rural life, rich in emotion, sometimes tinged with satire, and always deeply human. Director Satyajit Ray would later adapt several of these stories into films, capturing their tone and tenderness. Poems such as those in Sonar Tari (The Golden Boat, 1894) and plays like Chitrangada (1892) also date from this period, showcasing a growing mastery of form and theme.

The Many Lives of Tagore: Writer, Musician, Philosopher, Educator

By the time the 20th century rolled around, Tagore had become a household name in Bengal. He went on to write over 2,000 songs, now known as Rabindra Sangeet, that blended Indian classical music with folk influences and poetic lyrics. These songs remain hugely popular across generations, sung in everything from school assemblies to concert halls.

His body of work is vast: Gora, Ghare Baire (The Home and the World), Shesher Kobita (The Last Poem), Chokher Bali, Rakta Karabi (Red Oleanders), and Tasher Desh (The Land of Cards) are just a few of his standout novels and plays. His writing spans love, politics, gender, faith, and the human condition, often with remarkable foresight and nuance.

But Tagore’s ambitions were never limited to the page. He despised rote learning and colonial-style education. In a satirical short story called The Parrot’s Training, he tells the tale of a bird force-fed textbooks until it dies, a thinly veiled attack on mindless education systems. His alternative was to create something more meaningful.

In Santiniketan, he founded a new type of school rooted in personal mentorship and outdoor learning. This became Visva-Bharati University, formally inaugurated in 1921. Its aim? To be a global centre for studying humanity, “beyond the limits of nation and geography”. Classes were often held under trees; students and teachers shared meals and ideas alike. Tagore donated his Nobel Prize money to fund the school and even wrote many of the students’ textbooks himself.

The Nobel Prize and the World’s Recognition

In 1913, Tagore received the Nobel Prize in Literature, becoming the first non-European to earn the honour. The work that brought him international acclaim was Gitanjali (Song Offerings), a collection of devotional poems translated into English. The book’s serene tone, spiritual depth and universalism caught the attention of literary luminaries like W.B. Yeats, who wrote the introduction to its English edition, and André Gide, who praised its quiet power.

In Yeats’s words:

“Mr Tagore, like the Indian civilisation itself, has been content to discover the soul and surrender himself to its spontaneity.”

It was a poetic expression of what made Tagore different—he didn’t write to impress, but to express something timeless and inwardly vast.

Politics, Protest and Principled Resistance

Though not a firebrand revolutionary, Tagore’s political views were deeply held. He opposed imperialism, supported self-rule, and was sharply critical of social inequality. His 1925 essay The Cult of the Charkha mocked empty nationalism and warned against mistaking political gestures for real progress. He was sympathetic to Indian revolutionaries, aware of movements like the Ghadar Party, and even sought support abroad, including from Japanese Prime Ministers.

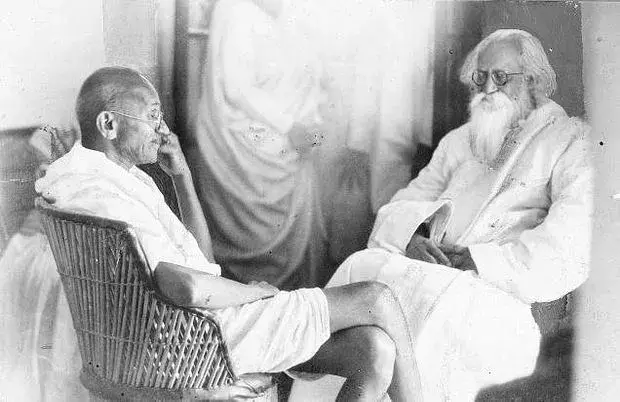

He and Gandhi had a cordial but complicated relationship. Tagore admired Gandhi’s goals but sometimes challenged his methods, especially when it came to mixing politics with religion. Yet he played a key role in mediating during the Gandhi–Ambedkar dispute on separate electorates for Dalits, helping prevent a deeper national rift.

Tagore also knew the cost of speaking out. In 1915, he was knighted by the British, but he renounced the title just four years later, in protest at the Jallianwala Bagh massacre in Amritsar. In a powerful letter to the Viceroy, Lord Chelmsford, he wrote:

“The time has come when badges of honour make our shame glaring in the incongruous context of humiliation… I for my part wish to stand, shorn of all special distinctions, by the side of those of my countrymen…”

Music for Nations, and Words for the World

Among his many achievements, one of the most unique is that Tagore composed the national anthems of both India and Bangladesh. Jana Gana Mana and Amar Shonar Bangla are still sung today with deep emotion—both poetic reflections of the people, the land, and the spirit of freedom.

Two of his other songs, Chitto Jetha Bhayshunyo (Where the Mind is Without Fear) and Ekla Chalo Re (Walk Alone), became cultural touchstones during the Indian independence movement. The latter was especially loved by Gandhi, despite their philosophical differences.

Science, Sadness and the Final Years

Tagore’s later years saw a growing interest in science and natural philosophy. He published Visva-Parichay in 1937 and wove scientific curiosity into short stories and essays, reflecting on biology, physics and astronomy with poetic flair.

But these were also years of personal grief. Between 1902 and 1907, Tagore lost his wife and two of his children. The pain of these losses is evident in much of his later poetry—haunting, tender, sometimes aching with absence. His final poem, dictated days before his death in August 1941, is a quiet meditation on life’s end:

I'm lost in the middle of my birthday. I want my friends, their touch, with the earth's last love. I will take life's final offering, I will take the human's last blessing. Today my sack is empty. I have given completely whatever I had to give. In return if I receive anything—some love, some forgiveness—then I will take it with me when I step on the boat that crosses to the festival of the wordless end.

He passed away in the same Jorasanko mansion where he had begun his life, aged 80. It was the end of an era—but not of his influence.

Why He Still Matters

To this day, Rabindranath Tagore remains a singular figure in Indian and global literature. His poetry resists translation but still travels. His songs, novels and plays continue to be adapted. His ideas about education, art, and humanity feel just as urgent now as they did a hundred years ago.

On Baishe Shrabon, Tagore isn’t just mourned—he’s re-read, re-sung, and re-loved. From schoolchildren humming Rabindra Sangeet to scholars studying his essays, his legacy lives on quietly, without fanfare, but with enormous depth.

He once said:

“Let your life lightly dance on the edges of time like dew on the tip of a leaf.”

Perhaps that’s how his work still lingers, light as dew, deep as a river, and always just around the next corner of thought.

Quotes to pop into your brain.

"...Where the clear stream of reason has not lost its way into the dreary desert sand of dead habit. Where the mind is led forward by thee into ever-widening thought and action. In to that heaven of freedom, my father, Let my country awake."

"Deliverance is not for me in renunciation. I feel the embrace of freedom in a thousand bonds of delight."

"And because I love this life, I know I shall love death as well.

"He who has the knowledge has the responsibility to impart it to the students."

"In the night of weariness let me give myself up to sleep without struggle, resting my trust upon thee..."

“If you cry because the sun has gone out of your life, your tears will prevent you from seeing the stars.”

“I slept and dreamt that life was joy. I awoke and saw that life was service. I acted and behold, service was joy.”

“The butterfly counts not months but moments, and has time enough.”

Comments