Victorian Hairwork and Its Many Meanings: Rethinking the Myth of the Mourning Wreath

- Daniel Holland

- Nov 29, 2025

- 7 min read

If you wander through antique shops or browse online listings today, you will inevitably come across a Victorian hair wreath displayed under glass, its delicate blossoms fixed to looping wire stems, its tendrils arranged in careful spirals. The seller might describe it with a lowered voice, invoking nineteenth century tragedy. “A mourning wreath,” they’ll say. “Made from the hair of the dead.”

It is a story people expect to hear, and an easy one to accept. The Victorians, after all, had a reputation for elaborate rituals of grief. They were a society who wrapped mirrors in black cloth, wore mourning jet for years, and staged photographic portraits beside coffins. It seems only logical that these intricate hair wreaths belonged purely to a world of sorrow and remembrance.

But that tidy narrative is wrong. Or, at best, only partially correct.

The idea that Victorian wirework hair pieces were mainly or even primarily mourning objects is one of the most enduring misconceptions in the study of nineteenth century material culture. As with many myths that thrive today, it is built on a fragment of truth that has been allowed to eclipse a much larger, more nuanced reality. Most Victorian hair wreaths, in fact, were made not from the hair of the dead, but from the hair of the living.

This broader truth reveals something far richer than the stereotype suggests. These pieces were sentimental, communal, genealogical, ceremonial, artistic, and sometimes competitive. They were made not only in sorrow but in joy, pride, affection, and creativity. One nineteenth century manual even insisted that the technique required “live hair, that is, hair from the head of a living person”, a detail that forces us to reconsider nearly everything we assume about these objects. Victorian women were not simply makers of mourning relics. They were artists, archivists, and ingenious craftswomen, shaping identity, community, and memory through a medium that was as intimate as it was enduring.

What follows is a journey through that wider world.

Hairwork in the Victorian Imagination: More Than Mourning

The Victorians lived at a time when hair held both practical and symbolic power. Its permanence made it an ideal material for keepsakes. Its intimacy made it personal. Its availability made it democratic. Hair could be kept without destroying anything. It could be transformed without diminishing the person from whom it came. It was both self and symbol.

The cultural historian Margaret Wharton once wrote that “Victorian sentiment was materialised through the smallest possible trace,” and nothing captured this better than a lock of hair.

Because Victorian mourning culture was so visible – so codified, so theatrical, so explicitly material – it is easy to conflate the existence of hairwork with the rituals of grief. But the record tells a different story. Most hairwork was not produced after death. It was instead a sign of affection, kinship, or celebration. These pieces appeared in parlours, not just because they honoured relatives, but because they represented an entire living community.

Many wreaths functioned like a family tree in three dimensions. Each curl of hair belonged to a specific individual. Children were represented next to parents, cousins with cousins, branches growing outward in literal, physical form. Some wreaths were made by entire church congregations, collecting strands from every member. Others were produced at community gatherings, where women exchanged hair as tokens of friendship.

The anthropologist Elizabeth Gaskell remarked in 1884 that “hair, being the most lasting part of the body, is the most suitable for tokens of love,” a line that captures why these objects were not confined to mourning alone. They expressed connection long before they expressed loss.

Sentiment, Friendship and the Art of the Living

In the nineteenth century, exchanging hair was a tender gesture, one far removed from the emotional reserve associated with the Victorian stereotype. Friends, lovers, siblings and parents all participated in the custom. Hair was braided into jewellery, set beneath crystal, or shaped into floral sprigs for display.

A great many of the surviving wreaths are sentimental works created from the hair of living relatives. They might include the hair of a newly married couple, a mother and her daughters, or a circle of friends attending school together. The emotional language behind them was far closer to the keepsake album or the autograph book than to the funeral relic. They recorded relationships that were active and ongoing.

These objects were displayed proudly in front parlours, not as reminders of death but as symbols of affection. To a Victorian visitor, a hairwork wreath signified intimacy and involvement. It was not morbid. It was deeply human.

Hairwork as Genealogy: An Embodied Family Tree

Some wreaths expand this idea even further. They act as literal genealogical records, mapping family lines through clusters of carefully arranged flowers. A typical family hair wreath might show branching compositions emanating from a central point, each new tendril marking the birth of a new generation. The arrangement expressed continuity. Its circular shape often symbolised unity or unbroken love.

In these cases, hair was not a memento of loss but a celebration of life in progress. Families sometimes worked on these pieces over decades, adding new hair as children were born or married. The result was a living archive, an evolving portrait of a household.

The historian Louise Price once described such wreaths as “the intimate census,” a phrase that captures their dual role as artistic objects and family documents. They formed a record more personal than signatures on paper, preserving a tangible part of each life.

Communal Hairwork: Congregations, Towns and Shared Identity

While family hair wreaths form the majority of privately held examples, the nineteenth century also produced wreaths that represented whole communities. These could include the hair of every member of a church congregation, a small town, a social club or a charitable society.

These communal wreaths were displayed in public buildings or meeting halls. Their purpose was symbolic, representing unity, cooperation and belonging. They visualised the collective body of the group in a literal material sense. Each person contributed something, however small. Each contribution was preserved.

Such pieces reveal an aspect of Victorian social life that is often forgotten: community crafts were not limited to quilts or samplers. Hairwork, too, could be a communal act.

Rites of Passage: Hairwork as Transformation

Hair did not only represent relationships. It also represented change. Some pieces commemorate life-changing moments: a young boy’s first haircut, a girl entering adulthood, a woman taking religious vows, or an individual undergoing a significant social transition.

The act of cutting hair itself could be ceremonial. In some cases, the hair was formed into small framed arrangements. In others, it was shaped into a floral motif or simple wreath. The meaning here differed from mourning entirely. These works captured transformation rather than loss.

One striking surviving example is a nun’s hair wreath created using the locks she cut upon entering her order. It embodies a symbolic death of worldly identity, but equally a celebration of new spiritual life. It is a relic of passage, not of death.

Hairwork as Pure Creativity: The Domestic Art of Fancywork

Not every Victorian hair wreath was sentimental at all. Some were created for no emotional reason whatsoever. They were art.

Hairwork entered the world of “fancywork,” a broad category of domestic crafts that included wax flowers, shellwork, glass etching, fern pressing, and feather art. Magazines and craft manuals published extensive instructions. Women held hairwork socials. State fairs displayed competitive hair sculptures.

Victorian newspapers even noted when artists purchased hair in bulk, proving that many pieces were not personal memorabilia at all. A delightful example appears in the Bourbon News of Kentucky, 15 September 1882, describing an enormous wreath nearly three feet across, noted as “the handsomest piece of fancywork shown at our fair.” The writer adds that it required “ten months’ arduous labour and ten thousand dollars’ worth of hair and patience” to complete. The artist clearly bought hair specifically for the project, chosen for quality rather than sentiment.

Some creative pieces pushed the limits of domestic craft. They were enormous, meticulously symmetrical, or technically ambitious. They functioned as displays of skill, not emotion.

Why We Misread Victorian Hairwork Today

If hairwork served so many different purposes, why do modern audiences assume it was always made for mourning?

The answer lies partly in what survives and partly in how modern sensibilities interpret the past. Hairwork that commemorated the dead was more likely to be intentionally preserved. Sentimental or creative pieces were often discarded as tastes changed. As a result, the surviving examples are disproportionately memorial in tone, skewing our perception.

Furthermore, Victorian mourning culture has become a kind of shorthand for the entire period. Popular culture gravitates toward the macabre, reinforcing a stereotype that all nineteenth century sentimentality was morbid. In reality, Victorian emotional life was far more varied.

Reading the Clues: How Historians Interpret Hairwork Today

Without the original documentation, it can be difficult to determine the exact intention behind a piece of hairwork. Many wreaths have lost their labels, their notes, their family stories. As a result, historians must read them carefully, using material, structure, and iconography as clues.

A wreath with a completed circular shape usually gestures toward unity or continuity. An open circle, horseshoe shape, or broken loop can reference mourning. Grey hair in abundance might suggest old age, but not necessarily death. Uniformity of colour may indicate commercially purchased hair. Large quantities of one person’s hair could suggest either mourning or a rite of passage.

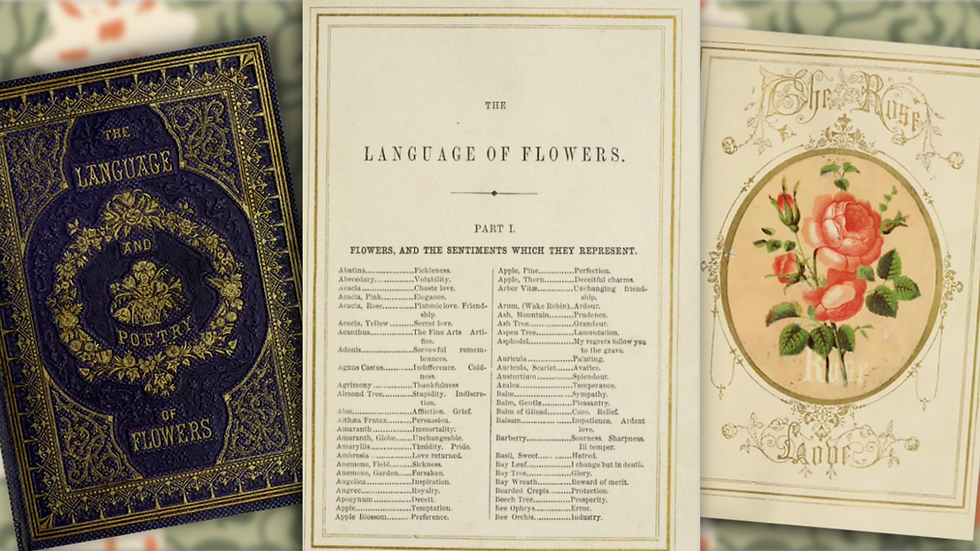

The design itself matters. Flowers such as pansies or forget-me-nots can symbolise affection rather than mourning. Traditional mourning symbols such as willow trees, urns or funerary landscapes strongly tilt toward memorial intent. Elaborate casket-style linings often indicate mourning, yet they were also sometimes chosen simply because they made the hair appear striking under glass.

Some wreaths reveal their history through repairs or additions. A piece may begin as a family tree of living individuals but later incorporate the hair of a deceased relative, creating a hybrid object that spans both celebration and loss. Such transitional pieces are among the most evocative, carrying a history of evolving meaning over time.

In the end, interpretation is rarely definitive. It is an act of informed analysis rather than certainty. What matters most is understanding that these pieces cannot be reduced to a single narrative.

Victorian Women as Artists, Archivists and Innovators

To limit the meaning of hairwork to mourning is to flatten the lived experiences of the women who made it. These were not passive relic-makers but remarkable craftswomen. They demonstrated technical precision, aesthetic vision, botanical knowledge, and extraordinary patience. In the act of transforming hair into flowers, they expanded the possibilities of domestic creativity.

Victorian hairwork represents a world where emotion, art, memory and craft intertwined. It asks us to broaden our view of nineteenth century women’s lives, their artistic pursuits, their relationships and their communal identities.

Most importantly, it reveals that the Victorians were not obsessed with death. They were obsessed with connection.

Sources

“The Art of Hair Work: Hair Braiding and Jewelry of Sentiment.” Self-published instructional manual, 1867.

“Fancy Work for Pleasure and Profit.” E. T. Girard, 1876.

Bourbon News, Bourbon County, Kentucky, 15 September 1882. “Society Scintillations.”

Gaskell, Elizabeth. “On Victorian Sentiment and Material Memory.” 1884 archival extract.

Wharton, Margaret. “Tokens of Affection: Hairwork and Sentimental Craft.” Journal of Victorian Material Culture Studies.

Comments