The Polaroid Calling Cards of Southern California Strip Clubs

- Daniel Holland

- Dec 19, 2025

- 5 min read

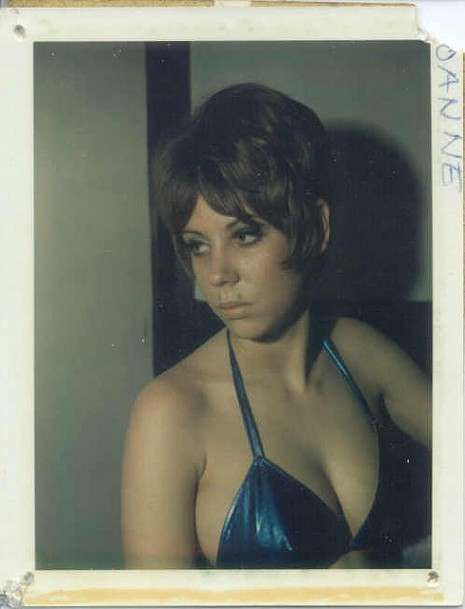

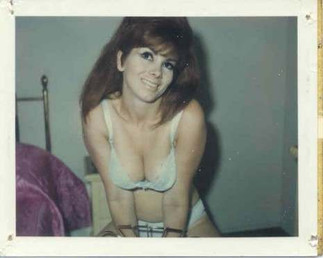

In the dimly lit clubs of Southern California during the late 1960s and early 1970s, a small square photograph could carry far more weight than a business card. Taken on the spot, warm to the touch as the image slowly emerged, Polaroid photographs became an improvised form of self-promotion for strippers working the region’s rapidly expanding nightlife circuit. Long before social media, websites, or even affordable colour printing, these instant photographs functioned as a practical and highly personal calling card.

They were modest objects, easily overlooked today, but at the time they sat at the intersection of new technology, informal labour markets, and the realities of working women navigating a cash-based economy.

Southern California and the Changing Club Scene

By the late 1960s, Southern California had become a hub for adult entertainment. Los Angeles, Orange County, and parts of San Diego County supported a dense network of strip clubs, go-go bars, and topless venues. These spaces were shaped by shifting obscenity laws, postwar leisure culture, and the migration of young people to California’s cities.

Strip clubs operated in a legal grey zone. Performers were rarely employees in the modern sense. Instead, they worked as independent contractors, paying stage fees or sharing tips with management. This meant that self-promotion was not optional. Dancers needed to cultivate regulars, private clients, or off-club work in order to earn a stable living.

In this environment, visibility mattered. Names were forgotten, faces blurred together, and handwritten phone numbers could easily be lost. A photograph offered something more concrete.

The Arrival of the Polaroid Camera

The Polaroid Land Camera, first introduced in the late 1940s, became widely accessible by the 1960s. Its defining feature was instant development. A photograph could be taken and produced within minutes, without a darkroom or specialist equipment.

By the late 1960s, Polaroid cameras were increasingly common in private homes, parties, and informal workplaces. They were portable, relatively affordable, and required no technical expertise. This made them particularly useful in settings where speed and discretion mattered.

For performers, the Polaroid solved several problems at once. There was no need to book a professional photographer, no paper trail left at a photo lab, and no delay between taking the image and handing it over. The photograph existed as a single physical object, easily controlled by the person who created it.

The Polaroid as a Calling Card

The photographs used as calling cards were typically small format Polaroids, usually square, bordered by the familiar white frame. The image itself was informal. Some were taken backstage, others in dressing rooms or quiet corners of the club. Lighting was uneven, poses were relaxed, and clothing ranged from stage costumes to everyday wear.

This informality was part of the appeal. Unlike studio glamour shots, these images felt immediate and personal. They suggested access rather than polish.

The photograph functioned as both a reminder and a point of contact. It allowed the recipient to remember not just a name, but a face, a hairstyle, a mood. In an era when mobile phones did not exist and addresses changed frequently, this visual anchor mattered.

Label Makers and DIY Typography

What completed the calling card was not handwriting, but adhesive text. Many performers used handheld label makers to add their name, stage name, or phone number directly onto the Polaroid border.

The Astro Label Maker, frequently mentioned in recollections from the period, was a popular choice. These devices embossed raised white letters onto coloured plastic tape, often black or red. The tape could be cut by hand and pressed onto the photograph.

The result was distinctive. The lettering was uniform, slightly clunky, and unmistakably mechanical. In contrast to cursive handwriting, it conveyed a sense of intention and permanence.

This was practical as well as aesthetic. The embossed letters were difficult to smudge or fade, and the adhesive tape held firmly to the glossy Polaroid surface. The label maker allowed performers to produce multiple cards quickly, updating phone numbers as needed without starting from scratch.

Labour, Autonomy, and Control

These Polaroid calling cards were not officially sanctioned marketing materials. They were produced independently, often quietly, and distributed selectively. This mattered in a working environment where control over one’s image was limited.

Strip clubs imposed rules about appearance, behaviour, and sometimes even movement outside the club. By creating their own photographs, performers exercised a degree of autonomy. They decided how they were represented, who received the image, and what information was shared.

The physicality of the Polaroid also mattered. Unlike magazine photographs or posters, these images were not mass-produced. Each one was singular. Once given away, it could not be replicated without the subject’s participation.

In that sense, the Polaroid calling card offered a form of control in an industry that otherwise offered very little.

Before Digital Identity

Seen from a contemporary perspective, these photographs resemble an early analogue version of a social media profile. They combined image, name, and contact details into a single object designed to prompt future interaction.

What distinguishes them from modern digital equivalents is their fragility. Polaroids could be bent, faded, or lost. Phone numbers changed. Clubs closed. The object had a lifespan tied closely to the moment it was created.

This impermanence reflected the working realities of the time. Many performers moved frequently, both geographically and professionally. The calling card was useful precisely because it required no infrastructure beyond the performer herself.

Collectability and Survival

Very few of these Polaroid calling cards survive today. They were not created to be archived. Many were discarded, damaged, or intentionally destroyed. Those that do exist tend to surface in private collections, flea markets, or estate clearances, often detached from any identifying information.

When they do appear, they offer a rare glimpse into an informal visual culture rarely documented by institutions. Museums and archives traditionally focused on official photography, commercial studios, or celebrity imagery. These small, personal photographs fall outside those categories.

Yet they reveal a great deal about technology, gendered labour, and everyday creativity in mid-20th-century America.

A Small Object with a Wider Story

The Polaroid calling cards of Southern California strip clubs were simple objects. They required no specialised training, no approval, and no capital investment beyond a camera and a label maker. Yet they represent a moment when new technology quietly reshaped how people presented themselves and managed their working lives.

They remind us that innovation does not always arrive through grand design. Sometimes it appears in the margins, adopted by those who need it most, and disappears again once its moment has passed.

In that sense, these faded photographs tell a broader story about adaptation, self-representation, and the material culture of work in a pre-digital world.

I have some of the pics shown that were given to me as a gift on my beer fridge that were turned into refrigerator magnets around 1990

Very interesting subject matter. Well written article.