Halloween Traditions 1900 to 1930: Mischief, Costumes and Fortune-Telling Games

- Oct 27, 2025

- 6 min read

Today, Halloween is often thought of as a very American affair, with trick-or-treating, supermarket costumes, and pumpkins on every doorstep. But if you look back to Europe in the early 20th century, you find a different picture. Between 1900 and 1930, Halloween on this side of the Atlantic was still closely tied to older folk customs, particularly in Ireland, Scotland, and parts of Britain, with echoes of Celtic and Christian traditions shaping the way people marked the night.

This was a period when the holiday was less about commercial goods and more about bonfires, games, mischief, and superstition. In many communities, it was also a time to celebrate the harvest, court romance through fortune-telling, and honour old beliefs about the thin veil between the living and the dead.

A Legacy of Samhain

Halloween’s European roots lie in the ancient Celtic festival of Samhain, which marked the end of the harvest season and the beginning of winter. By the 20th century, the Christian church had long since overlaid this with All Saints’ and All Souls’ Days, but traces of Samhain lingered in folk practices. In rural Ireland and Scotland, people still lit bonfires on hillsides at the end of October, believing the flames offered protection against wandering spirits.

In these areas, Halloween was not just an evening of fun but part of the yearly cycle of farming life. It was tied to the rhythms of harvest, the fear of the coming winter, and the hope for prosperity in the year ahead.

Mischief in the Villages and Towns

European Halloween was also associated with tricks and mischief. In Scotland, young people often went “guising,” dressing up in costumes and visiting neighbours to perform songs or rhymes in exchange for fruit, nuts, or small coins. Unlike modern trick-or-treating, the exchange required effort. A child had to sing, recite, or tell a joke to earn their reward.

Pranks were also common. Knocking on doors and running away, rearranging gates, and covering windows with soot were favourite tricks among the young. Reports from Scottish and Irish villages in the early 1900s note that groups of boys sometimes took their antics too far, damaging property or causing sleepless nights for entire streets. This mirrors the complaints found in English towns, where “Mischief Night” activities often stretched across late October.

Fortune-Telling and Courtship Games

Perhaps the most distinctive part of European Halloween in the early 20th century was the persistence of fortune-telling games. These were especially popular among young women, who saw the holiday as a time to gain hints about future romance.

In Ireland, barmbrack, a type of fruit loaf, was baked with small objects hidden inside. Each item had a symbolic meaning: a ring foretold marriage, a coin suggested wealth, a piece of cloth hinted at misfortune. Families would cut and share the loaf, each member discovering their “fortune” in the slice they received.

Apple-based games were widespread too. Bobbing for apples was a familiar sight, but other variations existed. In some parts of Britain, apples were hung from strings and players had to try to bite them without using their hands. Another tradition involved placing apples in water and attempting to spear them with a fork held between the teeth. Success in these games was thought to promise good luck in love.

Nuts also carried symbolic weight. In Scotland, two hazelnuts were placed side by side in the fire, each representing a potential couple. If the nuts burned steadily together, it meant a lasting bond. If they popped apart, the romance was doomed. These games added a playful, flirtatious element to gatherings and ensured that Halloween was remembered not only for mischief but also for courtship.

Bonfires and Community Gatherings

In rural parts of Ireland and Scotland, bonfires remained an important part of Halloween well into the early 20th century. These fires were not simply decorative. They were thought to protect against evil spirits and bad luck, echoing the ancient Samhain rituals where people lit great communal fires and carried embers home to relight their hearths.

Children and adults alike gathered around these bonfires for singing, storytelling, and games. In some places, stones were placed in the fire to represent family members. If a stone was missing in the ashes the next morning, it was taken as a bad omen for the year ahead.

These gatherings created a strong sense of community, particularly in rural villages where Halloween was one of the most anticipated events of the year.

Costumes and Guising

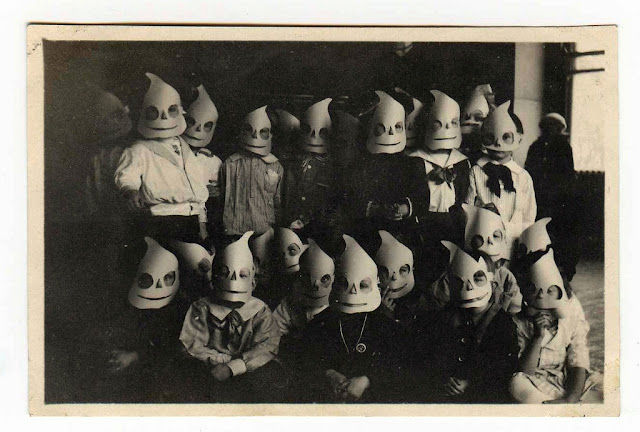

Costumes in early 20th-century Europe were simple and often homemade. Children disguised themselves with masks, old clothes, or sheets, and went door to door to perform for their neighbours. This practice, known as guising, was especially strong in Scotland and parts of Ireland. Unlike the American practice that developed later, guising was less about demanding treats and more about entertaining in exchange for tokens of appreciation.

Masks were often crude, sometimes made of paper or cloth. They carried a sense of mystery, with the disguise adding to the atmosphere of the night. The purpose was not always to look frightening, but to conceal identity, play a role, or invoke figures from folklore.

Food and Seasonal Fare

Halloween in Europe was also tied closely to food traditions. Beyond barmbrack in Ireland, colcannon, a dish of mashed potatoes with kale or cabbage, was served at Halloween gatherings. Small charms might be hidden in the dish in the same way as in the fruit loaf, each carrying symbolic meaning.

Roasted nuts, apples, and parkin (a type of gingerbread cake) were common in Britain. In Scotland, sowans, a kind of porridge made from oat husks, was a traditional Halloween dish. These foods reflected the season, making use of harvest ingredients while also adding an element of fun through hidden charms.

The Influence of America

By the 1920s, European Halloween was beginning to feel the pull of American influence. Immigrants from Ireland and Scotland had carried their traditions across the Atlantic, where they evolved into the more commercial Halloween that we recognise today. From the United States, postcards, decorations, and new ideas about costumes began filtering back to Europe.

In Britain, Halloween parties in the 1920s and 1930s began to feature more decorative touches, often inspired by the American market. Shops sold paper lanterns, masks, and themed decorations. However, the holiday never became as commercially dominant in Europe as it did in the United States. Instead, it retained a balance of old folk practices and new influences, resulting in a holiday that looked slightly different depending on where you stood.

A Holiday of Continuity and Change

Between 1900 and 1930, Halloween in Europe remained deeply tied to tradition. Bonfires, fortune-telling, guising, and seasonal foods all kept their place in communities, particularly in Ireland and Scotland. At the same time, the holiday was slowly changing. American ideas about parties and decorations began to appear, and the first stirrings of commercial Halloween reached European shores.

It was a period of continuity and change, where old customs lingered but new possibilities emerged. Today, when pumpkins and plastic costumes dominate, it is easy to forget that only a century ago Halloween in Europe was less about consumer goods and more about gathering around fires, peeling apples for omens, and reciting rhymes at neighbours’ doors.

Sources

Sir James George Frazer, The Golden Bough: A Study in Magic and Religion (abridged edition, 1922) – covers Celtic seasonal rites, including Samhain.

Ruth Edna Kelley, The Book of Hallowe’en (1919) – one of the first books in English devoted entirely to Halloween traditions, with focus on Ireland, Scotland, and America.

Alexander Montgomerie Bell, Folklore of Scotland (1913) – includes accounts of guising, nut-burning games, and Halloween charms.

The Scotsman (Edinburgh), 1 November 1905 – reports of Halloween mischief and guising in Scottish towns.

Irish Independent (Dublin), 31 October 1927 – coverage of Halloween bonfires and barmbrack customs.

Marie Trevelyan, Folk-Lore and Folk-Stories of Wales (1909) – includes references to Halloween divination practices in rural Wales.

T. F. Thiselton-Dyer, British Popular Customs: Present and Past (1900 reprint) – catalogues traditional Halloween games and superstitions across Britain.

Dennison Manufacturing Co., Bogie Book (first issued 1912, annual editions through the 1920s) – though American, influential in shaping decorative Halloween traditions that began to reach Europe by the late 1920s.

Steve Roud, The English Year (2006) – modern folklorist’s overview, with references back to early 20th-century practices.

Ronald Hutton, The Stations of the Sun: A History of the Ritual Year in Britain (Oxford University Press, 1996) – provides historical context on Halloween as celebrated in Britain and Ireland.

Comments