The 'Monowheel' - An Invention That Didn't Catch On

- Jul 30, 2024

- 7 min read

Updated: Sep 9, 2025

Picture this: it’s the 1930s and you’re standing at the edge of a demonstration ground in England. Out rumbles a machine that looks like a giant tyre with a man sitting inside it. The crowd gasps as the device lurches forward, gathering speed until it’s rolling smoothly across the field. The driver looks calm, almost futuristic, cocooned inside this strange invention. This is Dr. J.H. Purves’ Dynasphere, the most famous monowheel ever built.

For decades, inventors dreamed that the monowheel—or monocycle—would transform transport. From early pedal-powered contraptions in the 1860s to roaring petrol-fuelled monsters of the 1930s, it seemed destined to be the next great leap forward. Yet today, the monowheel is remembered more as a curiosity than a revolution.

Why did such an imaginative invention never catch on? Let’s roll back through history and explore the strange tale of the one-wheeled wonder that never became more than a sideshow.

The Origins: A French Curiosity in 1869

The first recorded monowheel appeared in 1869, invented by a Frenchman whose name has sadly faded into obscurity. His design wasn’t a pure monowheel in the way later machines were—it had a large outer wheel with a smaller wheel inside, connected by pedals. The rider sat in the middle and pedalled the smaller wheel, which pushed against the larger one, setting the whole contraption in motion.

At the time, bicycles were still relatively new, and cycling itself was seen as daring. Against this backdrop, the monowheel looked positively eccentric. Observers quickly pointed out its limitations, dismissing it as “impracticable for ordinary mortals.” Still, the seed was planted: if humans could travel atop two wheels, why not inside just one?

The Age of Experimentation

The late 19th and early 20th centuries were a golden age for inventors. Workshops across Europe and America buzzed with experiments in bicycles, early motorcycles, flying machines, and even personal submarines. The monowheel was one of many ideas that reflected this spirit of technological daring.

Monowheels operated on a simple principle: the rider sat inside a smaller inner frame, which carried the seat, pedals, or engine. This inner frame was suspended within a larger outer wheel, which rolled along the ground. Motion came either from human power (pedals or cranks) or, later, from engines attached to the inner frame.

Unlike a bicycle or unicycle, where the rider balanced above the wheel, the monowheel placed its operator inside, creating a strange sensation of being carried forward by a rolling cage.

Human-Powered Designs: Pedals and Problems

Throughout the late 1800s, inventors tinkered with pedal-powered monowheels. These machines looked impressive, but they had several fatal flaws.

Visibility: the rider’s line of sight was often blocked by the frame of the wheel.

Steering: without handlebars, direction was controlled by subtle shifts of weight and small mechanisms inside the wheel.

Balance: although gyroscopic forces kept the machine upright when moving, stopping or starting was fraught with difficulty.

Still, exhibitions and fairs occasionally showcased monowheels, where they drew fascinated crowds. Like many inventions of the period, they were as much about showmanship as practicality.

The Leap to Engine Power

The turn of the 20th century brought the internal combustion engine into the picture. Cars were emerging as a realistic form of personal transport, and motorcycles were beginning to appear on roads. Monowheel inventors saw an opportunity: why not harness petrol power to make their designs faster, stronger, and more practical?

Some designs added propellers to the front of the wheel, borrowing from aviation. Others experimented with chain-driven systems to rotate the outer wheel. The dream was simple—create a compact, efficient vehicle that was lighter and cheaper than a car but more stable than a motorcycle.

Unfortunately, reality didn’t match the dream. Engines gave monowheels speed, but they also amplified their weaknesses. Steering became more precarious at high speeds, braking was virtually impossible, and sudden acceleration risked throwing the rider into the dreaded phenomenon known as “gerbiling.”

Gerbiling: The Monowheel’s Fatal Flaw

“Gerbiling” is the term enthusiasts use for what happens when the inner frame of a monowheel begins to rotate within the outer wheel. Imagine suddenly braking or accelerating—the inertia causes the rider and inner frame to spin forward or backward inside the wheel, just like a gerbil in its running wheel.

It was not only undignified but also dangerous. Riders risked injury from being thrown around inside the machine, and once momentum was lost, regaining control was extremely difficult.

For a mode of transport intended for public roads, this was a fundamental problem.

The Dynasphere: Dr. Purves’ Vision

The most famous monowheel of all was the Dynasphere, built by Dr. J.H. Purves in 1932. Purves believed passionately in the concept, calling it:

“The logical simplification of all motor-driven transport.”

His design was striking: a massive circular frame resembling a tyre, with the driver seated inside an enclosed cabin. Unlike earlier open-air monowheels, the Dynasphere had a degree of protection, with metal framing and glass windows.

The Dynasphere was petrol-powered and could reach speeds of 25–30 mph. Purves even demonstrated it to the press, driving it across beaches and fields. Newspapers of the day ran photos of the eccentric-looking vehicle, hailing it as both futuristic and absurd.

Purves was convinced the Dynasphere would become a commercial success, but once again, its flaws became apparent. Stability was poor, passenger capacity was limited, and practical issues like steering and braking made it unsafe for everyday use. Investors weren’t willing to back it, and it faded into history as a curiosity.

High-Speed Experiments in Italy

Around the same time, Italian inventor M. Goventosa de Udine created a monowheel motorcycle capable of speeds up to 93 mph (150 km/h). On paper, this was a marvel, faster than many motorcycles of the era. In practice, it was almost impossible to control. At such speeds, even small shifts in balance could send the entire machine veering dangerously.

The Italian monowheel remained a fascinating prototype, but it was never developed further.

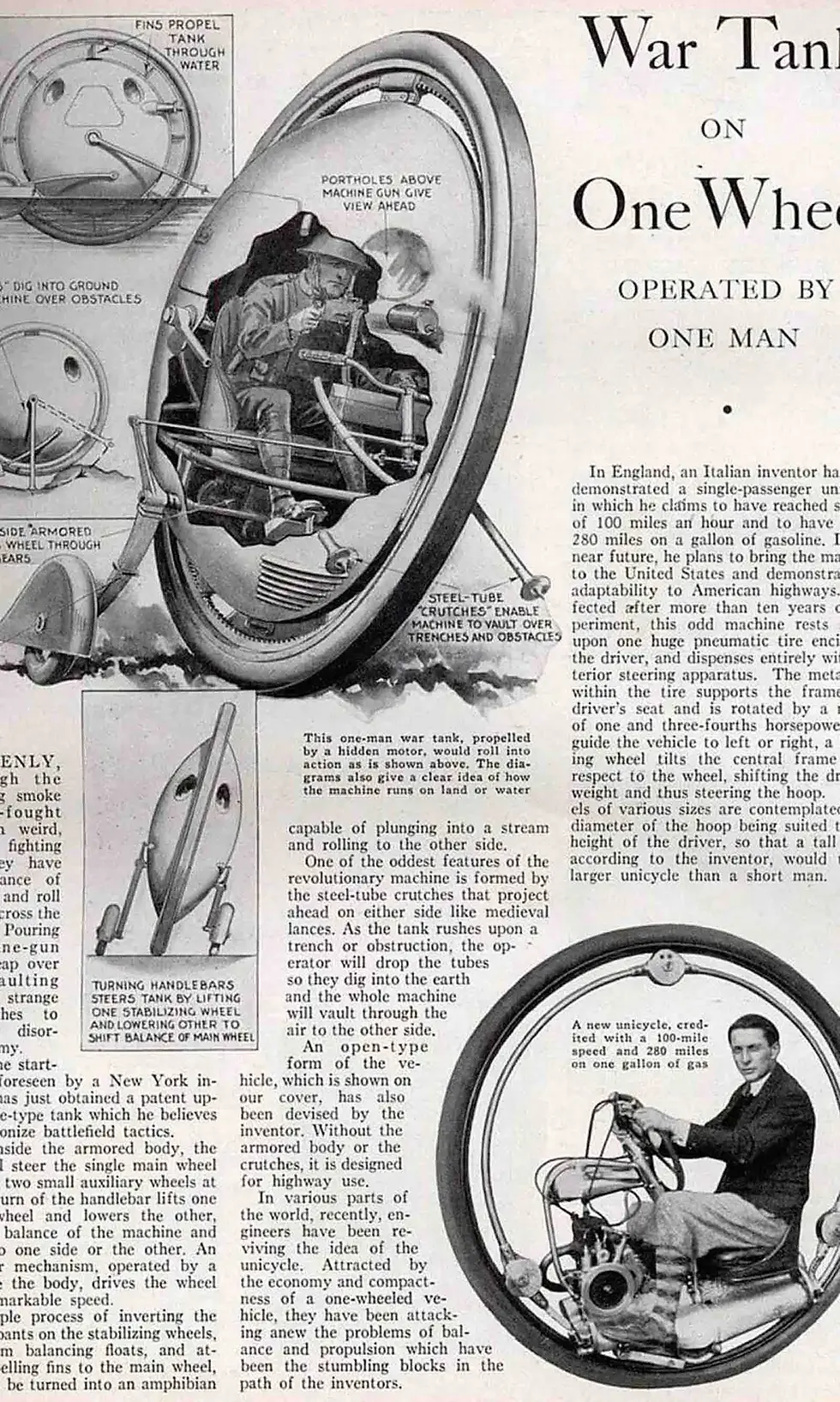

Futuristic Dreams in Print

Even as real-world monowheels struggled, scientific magazines of the 1930s loved to publish speculative illustrations of futuristic monowheel cars. Artists imagined sleek, glass-enclosed pods rolling smoothly along city streets, sometimes with space for multiple passengers.

These designs tapped into the interwar fascination with streamlined modernity. They appeared alongside drawings of flying cars, underwater trains, and rocket ships—visions of a future where technology would solve all human problems.

In reality, of course, the humble four-wheeled car proved far more practical.

Why the Monowheel Failed

Looking back, it’s clear why the monowheel never became more than a sideshow:

Instability: the design depended on forward motion to stay upright.

Poor braking: stopping safely was difficult, especially at higher speeds.

Steering challenges: unlike bicycles and cars, monowheels lacked intuitive controls.

Visibility issues: the rider’s position inside the wheel restricted their view.

Limited capacity: most monowheels could only carry one passenger.

Danger factor: the risk of gerbiling made them fundamentally unsafe.

While monowheels floundered, cars and motorcycles advanced rapidly, becoming cheaper, safer, and more reliable. By the 1930s, the battle was already lost.

The Monowheel in Culture and Memory

Despite their failure as practical vehicles, monowheels retained a hold on the imagination. Their bizarre appearance ensured they remained favourites in newsreels, exhibitions, and later, in science fiction.

Films and TV: Monowheel-like designs have appeared in futuristic settings, from steampunk stories to dystopian worlds.

Video games: Designers often use monowheels to symbolise eccentricity or futuristic flair.

Comic books: Villains and mad scientists are sometimes depicted riding them, underlining their quirky, impractical nature.

In this way, the monowheel became less a serious invention and more a symbol of eccentric futurism.

Modern Enthusiasts and Record-Breakers

While the monowheel never entered mass production, a small group of enthusiasts continues to build and ride them. Modern materials and engineering have solved some of the old problems, though not all.

Guinness World Records recognises modern monowheel speed attempts, with riders achieving over 70 mph.

DIY builders experiment with electric monowheels, often sharing their creations online.

Stunt shows occasionally feature monowheels, capitalising on their spectacle.

One striking example is the British group of monowheel enthusiasts who gather for demonstrations, celebrating the eccentric invention as both engineering challenge and entertainment.

The Monowheel and the Rise of Personal Transport

Interestingly, the monowheel can be seen as a distant ancestor of today’s experiments in personal mobility devices. Hoverboards, self-balancing electric unicycles, and even Segways share the same spirit: compact, unusual vehicles that challenge traditional ideas of transport.

The difference is that modern machines use gyroscopes, sensors, and computer control to maintain balance, something 19th- and early 20th-century inventors could only dream of.

In this sense, the monowheel wasn’t a failure so much as a vision ahead of its time.

Conclusion: A Fascinating Dead End

The monowheel is one of those inventions that captures the imagination even as it highlights the limits of human ingenuity. It looked futuristic, it worked (sort of), and it symbolised the daring optimism of inventors who believed the world could be reshaped by wheels, gears, and engines.

But practicality won out. The car, the motorcycle, and the bicycle all offered safer, easier, and more reliable ways to travel. The monowheel, with its wobbling frame and gerbil-like hazards, was left behind.

Yet its story is far from wasted. Today, photographs of giant rolling wheels from the 1930s remind us that progress is not always straightforward. Sometimes the strangest inventions are the ones that best reflect the adventurous spirit of their age.

As Dr. Purves once said,

“The wheel is the perfect motion.” He wasn’t wrong. He just picked the wrong wheel."

Sources

Popular Mechanics – “This Guy Built a Giant Motorized Monowheel”

https://www.popularmechanics.com/cars/a22935/monowheel-vehicle-history/

Guinness World Records – “Fastest monowheel motorcycle”

https://www.guinnessworldrecords.com/world-records/fastest-monowheel-motorcycle

Science and Society Picture Library – Images of the Dynasphere, 1932

New York Times Archive – “British Inventor Shows His Dynasphere” (1932)

National Motor Museum, Beaulieu – Dynasphere Collection Entry

Smithsonian Magazine – “The Monowheel: A Motorized Vehicle That Never Caught On”

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/innovation/the-monowheel-vehicle-that-never-caught-on-180972737/

“Monowheel Vehicles” – The Old Motor (vintage motoring history blog)

British Pathé Archive – Footage of the Dynasphere, 1932

Wired – “A Brief History of the Monowheel”

Cycling History and Inventions Archive – Pedal-Powered Monowheel, 1869

Comments