On a Mission from God: The Chaotic Making of The Blues Brothers

- Dec 6, 2025

- 31 min read

If you want to know what being a film executive looked like in Hollywood in 1979, picture this. Before sunrise, the head of Universal Pictures would sit up in bed, reach for the phone and wait for a voice three time zones away to read him 'The Numbers'. Every dollar spent. Every box office receipt. Every alarming indication that something somewhere on his studio lot was getting out of control.

That morning, The Numbers pointed directly at one film. A loud, chaotic, funny, unclassifiable project being shot by two Saturday Night Live veterans who wanted to honour American blues music while simultaneously smashing more automobiles than any comedy had ever attempted. Lew Wasserman, the man receiving the call, knew only one thing. The Blues Brothers was already wildly over budget.

He shouted for Ned Tanen, the Universal executive who had vouched for the picture. Tanen shouted for Sean Daniel, the production vice president. Daniel called director John Landis, who was somewhere in Chicago wondering whether he would manage to locate John Belushi before lunch.

The truth was simple. There had never been a film quite like it, and there has not been one since.

This is the full story. The long, winding road that begins in a small Toronto club in 1973 and ends in one of the most chaotic, beloved films of all time.

A Toronto speakeasy and the night everything started

Dan Aykroyd had only recently turned twenty when he began running the 505 Club, a private late night bar in Toronto that opened after midnight for comedians, musicians and insomniacs who preferred dim lights and a permanent haze of cigarette smoke. Aykroyd was already an unusual figure. He had trained briefly for the priesthood, had mismatched eyes, spoke like a professor of strange sciences and was obsessed with the blues in a way that was closer to religious devotion than casual fandom.

One night in 1973 the back door burst open and John Belushi arrived as if carried on a gust of theatrical energy. He wore a leather jacket, a white scarf knotted like a character escaping a 1940s crime film and a cap that looked like it belonged to a Chicago taxi driver. He had been performing with the National Lampoon Radio Hour in New York and had stopped in Toronto to scout Second City performers. Aykroyd later said that the moment Belushi walked in, he knew something significant had entered his life.

The jukebox was playing a local blues band called Downchild. Belushi leaned in, listening.

“This is good,” he said. “What is it”

Aykroyd told him.

“Blues,” Belushi said, almost embarrassed. “I don’t listen to much blues.”

Aykroyd looked at him as if the answer were self evident.

“John,” he said, “you are from Chicago.”

Belushi started laughing. That laugh was enormous and affectionate. People who knew him later said it was the laugh that made you trust him instantly.

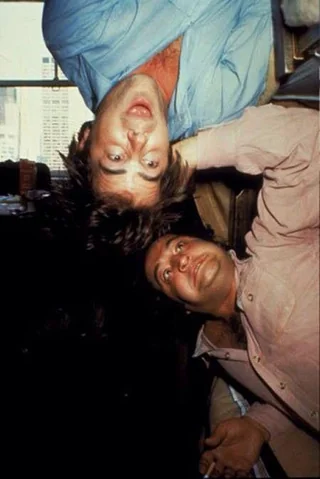

“We took one look at each other,” Aykroyd recalled, “and it was love at first sight.”

Belushi later told friends that Aykroyd had opened a door he did not know existed. He went back to New York with a suitcase heavier only because it was filled with blues records lent by Aykroyd.

Two opposites who fit perfectly

Belushi was a brilliant contradiction. He was confident but soft hearted. He was physically imposing but emotionally transparent. He hugged everyone. He made strangers feel like old friends. He had grown up in Wheaton, Illinois in a close Albanian American family and carried that warm, boisterous, kitchen table energy with him everywhere.

Aykroyd was precise. He spoke in carefully formed sentences. He had encyclopaedic knowledge of blues history and a fascination with everything from police scanners to UFO sightings to arc welding. He called people Sir. He looked at things like he was making mental notes.

Yet the pair clicked because of a shared sense of wonder. They were young men who believed that performance, music and mischief were all part of the same craft. They were outsiders, but they were outsiders who had found each other.

New York 1975 The rise of Jake and Elwood

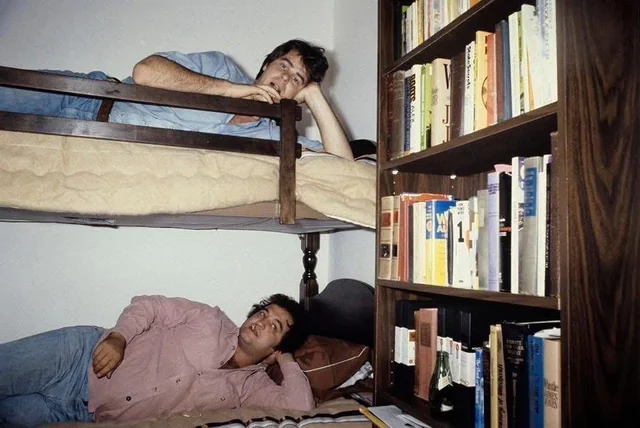

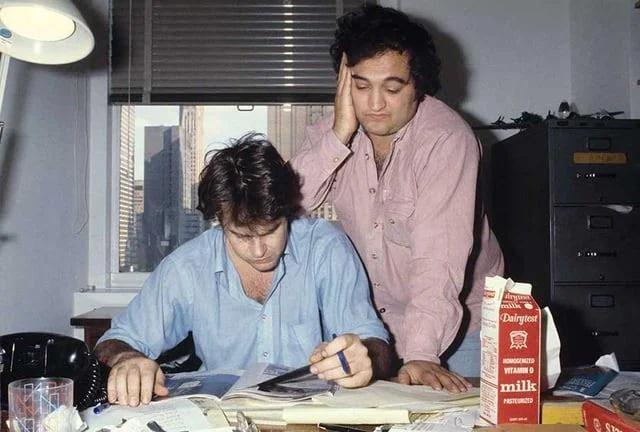

When SNL launched in 1975, Belushi and Aykroyd were among the original cast. New York was humid, anarchic and buzzing with creative energy. The cast worked through nights, living on adrenaline, cigarettes and whatever cheap food they could find.

Backstage, Aykroyd often brought his harmonica. Belushi loved the idea of performing music as much as comedy. The Blues Brothers idea bubbled for months before it ever reached the main stage. Howard Shore joked one night that they looked like brothers, and so the name stuck. Ron Gwynne helped Aykroyd craft the elaborate backstory. They were raised in an orphanage. They were taught blues by Curtis. They bled into a guitar string from Elmore James. It was half mythology and half affection.

They made their first appearance in January 1976 dressed as bees performing “I am a King Bee.” Aykroyd always said that although the sketch was silly, it let them smuggle blues onto national television.

In 1978, during a Steve Martin hosted episode, they performed “Hey Bartender” in their now iconic suits and sunglasses. Belushi instantly became Jake Blues. Aykroyd became Elwood. Something clicked.

Animal House changes the rules

Animal House opened in 1978 and Belushi became a star overnight. His character, Bluto, was instantly recognised everywhere. Aykroyd later told a story about driving with Belushi in Oregon. Belushi asked him to pull over by a school. Before Aykroyd could ask why, Belushi knocked on a classroom window. Seconds later the entire class was chanting “Bluto.”

Belushi was suddenly the most bankable comedic force in Hollywood. He could choose projects with real leverage. And what he wanted was to turn The Blues Brothers into a genuine band.

The band assembled with late night phone calls

When Steve Martin asked them to open nine shows at the Universal Amphitheatre, they realised they had a problem. They had an act but no band. Paul Shaffer produced a list of dream musicians. Men who played with Memphis Slim, Booker T, Sam and Dave and Stax Records.

Belushi called them himself. Often after midnight.

“This is John Belushi. We are putting a band together. I need you here tomorrow.”

Most musicians later said they agreed partly because of admiration and partly because Belushi did not seem capable of taking no for an answer. Steve Cropper recalled a phone call lasting almost an hour in which Belushi said nothing except “I gotta have you” in different tones.

The band came together. Cropper. Duck Dunn. Matt Guitar Murphy. Steve Jordan. Lou Marini. Tom Malone. Alan Rubin. Tom Scott. A set of musicians who could have headlined festivals on their own.

Their live performances were an explosion of joy. The rituals. The case opening with the harmonica inside. The dance steps. The comedic timing. Time magazine called them “the most unexpected supergroup of the decade.”

Atlantic Records recorded their set for Briefcase Full of Blues. It went double platinum.

Belushi said, “We should make a movie.”

Aykroyd said, “All right. Let’s do it.”

Universal buys enthusiasm and nothing else

Belushi’s power combined with Aykroyd’s imagination turned into a bidding war. Paramount wanted the film. Universal wanted it more because Sean Daniel had overseen Animal House and Belushi trusted him.

Lew Wasserman approved the project because Ned Tanen told him to. He did not yet know he was effectively signing a blank cheque.

There was no script. No schedule. No budget. Only a concept: Jake and Elwood go on a mission from God to save their orphanage.

Aykroyd began writing. He had never seen a screenplay. What he produced was more than 300 pages of single spaced free verse filled with deep lore, origin stories and entire chapters on recidivist American archetypes. He delivered it wrapped inside a phone book cover. Producer Bob Weiss called Sean Daniel and said, “We just got the script. It is enormous.”

John Landis took the document and disappeared for weeks. He emerged with a version that could be filmed. It preserved Aykroyd’s vision but added structure.

Landis told Aykroyd, “We have a movie.”

Casting legends and ignoring studio panic

The moment Universal realised who Aykroyd intended to cast, the conference room fell into the kind of silence usually reserved for budget meetings gone catastrophically wrong. Aykroyd listed the names without hesitation. Ray Charles. Aretha Franklin. James Brown. Cab Calloway. To him, these were not guest stars. They were the foundation stones of the music the entire film existed to celebrate.

To the studio, they were a problem.

It was 1979. Disco still dominated radio. Donna Summer and Gloria Gaynor filled the charts. The Hollywood executives who worried about marketing demographics saw nothing but risk in hiring performers whose biggest hits belonged to earlier decades. A Universal memo at the time described them politely as legacy acts, which was studio shorthand for artists who would not attract teenagers.

John Landis remembered the moment clearly. “They wanted someone younger. They said, why not Rose Royce They said the kids know Car Wash.” Belushi reportedly nearly fell out of his chair laughing. “We are not putting Car Wash in our film,” he said. “This is about blues and soul. This is the real thing.”

Belushi believed passionately in the music. He had absorbed the blues with a zeal that surprised even the musicians around him. Steve Cropper later said, “John loved that music more than some musicians I know. He was not faking it. He felt it in his bones.”

Aykroyd fought just as hard. He argued that Chicago was the birthplace of electric blues, that the film itself was a love letter, and that anything less than the real giants of the genre would betray the entire project. “If you are making a western,” he said in one meeting, “you hire cowboys. If you are making a film about blues, you hire the people who made the blues matter.”

Still the studio balked. There were genuine fears that young white audiences in suburban cinemas would not recognise or respond to artists whose careers peaked before many of them were born. Lew Wasserman was not opposed on artistic grounds but cared deeply about marketability. At one point an executive asked, very cautiously, whether they could add a disco sequence to broaden appeal. Landis said later, “I thought John was going to throw him out the window.”

Aykroyd remained calm but firm. “The whole point,” he said repeatedly, “is to honour the roots. If we do not bring Ray Charles and Aretha Franklin and James Brown and Cab Calloway into this, then what exactly are we doing”

Belushi backed him with the intensity of a man who simply refused to imagine another version of the film. “If Ray Charles is not in it,” he said, “then we are not doing it.”

Universal, realising the strength of their resolve, relented.

The musicians themselves approached the film with varying degrees of amusement, suspicion and relief. Ray Charles arrived on set wearing a grey suit and a grin that suggested he had no idea what the film was about but was delighted to be there. Aretha Franklin was warm but direct. Her first comment on reading her diner scene was, “Baby, I do not wear aprons.” Cab Calloway, ever the showman, delighted Aykroyd simply by agreeing to appear. Calloway insisted on performing Minnie the Moocher in the style of his 1930s big band recordings, complete with white suit and tails. James Brown treated his church sequence as if it were a real sermon. Extras later said it felt closer to a spiritual revival than a film shoot.

Landis said, “You could feel the mood change on set when they walked in. Everyone knew we were filming something important. This was not guest casting for novelty. These were giants.”

Wasserman still grumbled about the cost, but even he conceded privately that if the film was going to swing for the rafters, it might as well swing with the best.

The gamble paid off more profoundly than anyone predicted. Music critics later noted that The Blues Brothers did what no marketing department could have achieved. It reintroduced Ray Charles, Aretha Franklin, James Brown and Cab Calloway to new generations at a moment when their recording careers had slowed. After the film’s release, record sales rose again. Young audiences sought out the original tracks. James Brown later said that the film “put a whole new set of ears on my music.”

Aykroyd reflected, “If we brought even ten people to discover the blues because they saw Ray Charles play a keyboard in a pawn shop or heard Aretha Franklin sing about respect, then we did our job.”

It turned out to be many more than ten.

Chicago welcomes home a son

When filming for The Blues Brothers began in Chicago in July 1979, something unusual happened. Film crews were accustomed to being tolerated. Sometimes ignored. Occasionally resented. But Chicago did not merely tolerate this production. It embraced it. Adopted it. Lifted it. Because John Belushi had come home.

For all his fame in New York and Los Angeles, Belushi was profoundly shaped by Chicago. The city had fed his humour, his swagger, his sense of working class mischief. He was the son of Albanian immigrants from Wheaton. He grew up on neighbourhood jokes, football fields, and loud family dinners where everyone talked over each other. Chicago recognised him as one of its own. And Belushi, in his way, recognised Chicago right back.

Director John Landis recalled, “Being with John in Chicago was like being with Mussolini in Rome. People parted for him. They shouted his name. They hugged him. You could feel the city claiming him.”

The welcome was so intense that at times the production had trouble controlling crowds. When Belushi walked down a street, men leaned from bar windows shouting, “Johnny” Women stopped him for photos. Taxi drivers refused to take money. A police officer once saluted him as if greeting a decorated veteran.

Belushi adored it. But it had consequences. As Landis put it, “John could not go anywhere without being offered food, drinks or cocaine. Usually all three.”

Yet for all the chaos, Chicago gave the film texture it could never have manufactured on a studio lot. If New York is sharp edges and vertical ambition, Chicago is wide streets, steel bridges, open skies and the deep rumble of trains. It is the birthplace of electric blues and the spiritual heart of the film.

Jane Byrne and the city that opened its streets

Mayor Jane Byrne understood the value of films to Chicago’s identity, but she also understood the value of Belushi personally. Aykroyd later said, “We were welcomed like family. Jane Byrne treated us as ambassadors of the city.”

Permits were granted that would have been impossible in Los Angeles or New York. The Bluesmobile was allowed to tear through Lower Wacker Drive. Police cars swarmed the streets in choreographed formations. Whole blocks were shut down for scenes involving hundreds of extras, dozens of vehicles and some of the most audacious stunts attempted in an American comedy.

Film historian Michael Coate once observed, “The film could not have been made anywhere else. Chicago is not the backdrop. It is the third Blues Brother.”

The Dixie Square Mall legend

Perhaps the most extraordinary location was the Dixie Square Mall in Harvey. The mall had been abandoned for several years. Production designer John Lloyd visited it and saw opportunity where others saw ruin.

The crew spent weeks transforming the empty mall into a functioning shopping centre. They installed lights, filled shops with mannequins and merchandise, decorated displays and even brought in live-store signage. Then they drove cars straight through it.

The chase scene inside the mall became one of the most famous in film history. Lou Marini recalled standing nearby and hearing the shattering noise of displays exploding as the Bluesmobile fishtailed between shops. “I remember thinking, nobody will believe we actually did this,” he said.

The mall suffered such extensive damage that it was never reopened. For decades, urban explorers visited the ruins, calling it “the Blues Brothers Mall” until it was demolished.

Maxwell Street and the real sound of Chicago

The Maxwell Street Market sequence with John Lee Hooker was filmed amid real vendors and locals. Much of the dialogue captured there was improvised. A crew member later said, “We were not filming Chicago. Chicago was simply happening around us.”

Hooker played Boom Boom with such force that passers-by stopped to watch the shoot as if it were a genuine street performance. Aykroyd, listening from off camera, whispered, “This is everything the film is about.”

The Bluesmobile as a civic mascot

The Bluesmobile itself became a minor celebrity. Children shouted when they saw it drive past. One boy asked Aykroyd, “Is that a police car or a magic car” Aykroyd answered, “Both.”

The production destroyed so many police cars that a constant stream of replacements had to be brought in. At one point, Universal purchased sixty decommissioned cruisers at 400 dollars each. Mechanics worked round the clock to keep them running. Crew members joked that they were making two films. One about Jake and Elwood. One about the life cycle of a Dodge Monaco.

The day Chicago played the villain

The Illinois Nazis sequence required hundreds of extras, stunt performers and vehicles. The real Neo Nazi Party of America tried to protest the production. Aykroyd said later, “This was the only time we had genuine hostility. Everywhere else people were cheering for us.”

When filming the bridge confrontation, locals shouted insults at the faux Nazi extras, unaware they were actors. One extra later recalled, “Some guy threw a pretzel at me and called me every name under the sun. I thought, this is commitment to realism.”

A city that shaped the film’s soul

In the end, Chicago became the film’s heartbeat. Every street corner, every food stall, every bridge gave the movie its atmosphere. It was urban but warm. Gritty but generous. Funny without trying.

Aykroyd reflected years later, “We wrote the film as a love letter. Chicago gave us everything we needed and more.”

And for Belushi, filming there was something like a victory lap. His childhood city had not simply welcomed him back. It crowned him.

Belushi’s decline becomes impossible to ignore

For all the joy Chicago poured into John Belushi, the city also fed his worst tendencies. Fame made him magnetic. Chicago made him mythic. And myths attract people who want to touch the flame.

Belushi had arrived on set as a conquering hero, but as filming progressed, the adoration that once energised him grew heavier. Crowds gathered wherever he went. Bartenders handed him drinks he never ordered. Strangers offered him food, praise, homemade gifts and, increasingly, drugs.

Cocaine flowed so freely through Chicago nightlife in 1979 that one crew member later said, “It was like oxygen. You didn’t have to look. It found you.” And no one attracted it faster than John Belushi.

Carrie Fisher, who was dating Dan Aykroyd at the time, summarised the environment with wry understatement. “The bar staff all dealt on the side,” she said. “If you wanted anything, you only had to ask. Or not ask. It usually arrived anyway.”

The night time economy of being John Belushi

Belushi’s nights became complicated webs of admirers, local characters, after hours bars and unplanned detours. He was the person everyone wanted a story about. Smokey Wendell, a bodyguard later brought in to keep drugs away from him, explained it plainly.

“Every blue collar Joe wants a John Belushi story. They want to say they partied with him. They want to tell their mates that John Belushi did a line with them.”

Belushi was unable to refuse kindness, even when the kindness was destructive. Cocaine made him talkative, expansive, affectionate. It also made it harder to sleep and harder to get up in the morning. Unit calls slipped. Scenes slowed. Crew waited.

Landis said later, “We were shooting the film and simultaneously trying to keep John alive.”

The trailer incidents

The production developed a grim rhythm. Belushi would arrive late. Someone would knock on his trailer. No answer. A key would turn. Inside, the star would be asleep, shoes on, scripts scattered like fallen cards.

The worst moment came when Landis opened the trailer door and saw what he described as “a mountain” of cocaine piled on the small metal table.

“It looked like something out of a parody,” he said. “It was shocking. My instinct was to get rid of it. So I scooped it all up and flushed it.”

Belushi entered moments later and saw the empty table. He did not shout. He lunged. Landis said, “He pushed me, not to hurt me, but to get to the table. To see if any was left. It was heartbreaking.”

A few seconds later Belushi’s posture collapsed. He hugged Landis and began crying. “I know,” he said. “I know this is bad. I know.”

Both men sat there, shaking, the weight of the situation finally settling around them.

Aykroyd becomes the guardian

When Belushi’s behaviour threatened to derail the schedule, people went to Dan Aykroyd. Aykroyd had a calming influence on him. They shared a bond that was deeper than creative partnership. Aykroyd loved him. Belushi trusted him.

Aykroyd later said, “John could be the most gentle soul and the most chaotic soul. He was a brother to me. I would not abandon him. Ever.”

Crew members noticed that when Aykroyd entered Belushi’s trailer, the energy softened. Belushi would sit up, straighten his shirt, try to look sober even when he was not. It was not fear. It was respect.

Judy Belushi reminds him of home

Judy Belushi, John’s wife, visited Chicago frequently. She was kind, perceptive and unafraid to confront him. She described him as fundamentally quiet at home, happiest sitting on a sofa watching television, occasionally asking others to change the channel without words.

“He was not high octane by nature,” she said. “He had wonderful energy, yes, but he was actually very lazy in a sweet way. He liked people doing things for him. He liked being cared for.”

Chicago’s love fed the opposite version of him. Loud. Partying. Performing. Relentless.

Aykroyd and Judy tried privately to stabilise him. But neither could shield him from the city’s pull.

The disappearance in Harvey

The story that became set legend happened during a night shoot in Harvey, Illinois. Belushi vanished between takes. He did not answer walkie talkies. He did not answer knocks on his trailer door.

Landis became frantic.

Aykroyd closed his eyes, took a breath and simply walked away from the set. “I knew John,” he said. “I knew he would go where something was warm and lit.”

He followed a small track through the grass to a modest house with a single lamp on.

He knocked.

The homeowner, wearing slippers and a robe, opened the door and smiled in faint amusement.

“Oh, are you looking for your friend” he asked. “He came in an hour ago. Helped himself to a sandwich. He is asleep on the couch.”

Aykroyd found Belushi curled like a child, crumbs on his shirt, utterly peaceful.

“John,” Aykroyd whispered. “We have to go back to work.”

Belushi sat up, blinked and said, “Did I eat something”

They both thanked the bewildered but delighted homeowner. Belushi shook his hand and apologised. “Sorry, pal. Your fridge looked friendly.”

Landis later said, “Only John could break into a person’s house, fall asleep, and be loved for it.”

The problem no one could tell Wasserman

Ned Tanen could not tell Lew Wasserman what the real issue was. Wasserman wanted explanations for every delay, every overspend, every hour of lost time. He wanted reasons rooted in logistics, not the truth that his star was collapsing under the weight of adoration and addiction.

Tanen later said, “You could not say the words. You could not say the star was not functional. That would have ended the film. That would have cost millions. That would have sent the studio into a frenzy.”

So excuses were invented. Cameras malfunctioned. Weather changed. Extras got sick. Locations were rescheduled.

But everyone on set knew. Belushi was in trouble. And the film was tied tightly to him.

The highs, the lows and the illusions

Yet when Belushi was on screen, something magical happened. He was funny, sharp, present, alive. He delivered Jake Blues with a mix of swagger and vulnerability that felt impossible given his private state.

It created a strange illusion. When cameras rolled, he looked like the star everyone expected. When they stopped, he sometimes struggled to stand.

Steve Cropper later said, “When John was acting or singing, he became the version of himself he wanted to be. When it stopped, you could see him fighting gravity.”

Crew members described feeling protective, like caretakers watching a gifted child in peril.

Aykroyd said years later, softly, “We were all trying to save him. But he was pulled in all directions. Chicago loved him. Hollywood wanted him. People wanted stories. He wanted everything. And it was too much.”

Lew Wasserman reaches breaking point

While John Belushi drifted between moments of brilliance and chaos in Chicago, a very different type of storm brewed on the other side of the country. In Los Angeles, Lew Wasserman, the towering force behind Universal Pictures, was preparing for what many who worked under him privately called one of his volcanic mornings.

Wasserman was a man of habits. He began every day in precisely the same way. He sat up in bed at dawn, reached for the telephone and waited for The Numbers. These were not simply earnings reports. They were a meticulous breakdown of studio spending, projected revenue, production costs, overtime, re shoots, insurance claims and departmental overruns. Executives lived in fear of The Numbers because they revealed everything they had tried to conceal.

By the autumn of 1979, The Numbers brought increasingly grim news about a single production. The Blues Brothers.

The Numbers creep upward

It had begun modestly enough. A budget of around 12 million dollars. A comfortable figure for a comedy starring two rising television personalities. But as shooting began, the figures thickened like storm clouds. Police car repairs. Location fees. Stunt costs. Round the clock automotive mechanics. Sets built, rebuilt and destroyed. Weeks lost to delays. Additional catering because extras numbered in the hundreds. A creaking schedule.

Every day The Numbers rose. Every day Wasserman grew more alarmed.

Sean Daniel, the studio vice president overseeing the production, later described the atmosphere. “You could almost hear the anxiety. Every morning a sheet of paper would arrive, and with each day the sum became more impossible to explain.”

The fateful expression on Ned Tanen’s face

One morning The Numbers passed a threshold that Wasserman considered intolerable. He called for Ned Tanen, the executive who had championed the film. Tanen arrived looking slightly pale before the conversation even began. He knew what was coming.

Wasserman held up the paperwork. “This cannot be correct,” he said.

Tanen, who had already spoken privately to Daniel about the same issue, could only nod. He had no way to disguise the truth. The Blues Brothers was spiralling. It had become the most expensive comedy ever attempted.

Wasserman stared at the page as if inspecting a malfunctioning machine. “Chicago,” he said slowly, “is eating this film alive.”

Tanen knew the words were not a question. They were a verdict.

The emergency trip to Chicago

In a gesture that was equal parts damage control and reconnaissance, Tanen and Sean Daniel were dispatched to Chicago to see the situation firsthand. If they were going to report back to Wasserman, they needed to understand what exactly was happening on the ground.

What they discovered was a production unlike any they had encountered.

Daniel later summarised it as, “A controlled disaster. Beautifully executed. Terrifyingly expensive.”

The first shock came when they were shown the fleet of police cars. Row after row of battered Dodge Monaco cruisers. Some smashed. Some being welded back into shape. Some stripped for usable parts. It looked more like a scrapyard than a film set.

Mechanics worked in shifts, twenty four hours a day, repairing vehicles nearly as fast as Landis could destroy them. One mechanic joked, “We are not making a movie. We are making automotive history.”

Tanen reportedly stood still for a long time, absorbing the scene in silence.

The war room

Next they were shown the planning area, known internally as the war room. Hundreds of papers were pinned to cork boards. Stunt diagrams. Collision predictions. Street closures. Maps with arrows indicating routes for cars travelling at speeds rarely used outside police training courses.

Tanen frowned at one chart in particular. Daniel explained gently that it was a projection of vehicle destruction per day compared to budget allocation.

Tanen blinked slowly as though trying to decode a foreign language.

Then came the Dixie Square Mall story. Daniel was forced to explain, as diplomatically as possible, that production had located an abandoned mall, refurbished it to working condition and then driven cars through every major corridor. Tanen responded only with a quiet, “I see.”

The moment the blood drained

By the end of the visit, Tanen looked hollowed out. Daniel later recalled, “You could see the blood drain from his face. He realised the scale. He realised the cost. And he realised we could not rewind any of it.”

When they returned to Los Angeles, Wasserman did not need to ask questions. One look at Tanen’s expression told him everything.

The ultimatum that was never spoken aloud

Wasserman summoned Daniel privately. The studio head was not prone to theatrics. He did not raise his voice. He did not slam his fist. His displeasure was far more terrifying. He spoke quietly, in the tone of a doctor delivering a terminal diagnosis.

“This film,” Wasserman said, “is no longer a project. It is a liability.”

Daniel tried to defend the situation. He explained the enthusiasm of the cast, the artistry of Landis, the cultural value of the music, the importance of filming in Chicago. Wasserman listened without interrupting.

When Daniel finished, Wasserman simply said, “I want control restored. I want costs reduced. I want progress reported in hourly intervals.”

It was not rage. It was resolve.

The problem no one dared mention

There was, of course, one truth Wasserman did not know. One that Tanen could not tell him. The single greatest threat to the production was not money. It was John Belushi’s declining health.

To mention it would risk derailing the entire film. It would raise questions about insurability, schedule feasibility and the wisdom of continuing. Tanen said later, “We were juggling dynamite. You could not speak the truth. If Lew had known, he would have pulled the plug. And then millions would have been lost.”

So Wasserman continued to press for financial explanations while everyone in Chicago prayed that Belushi would hold together long enough for the film to finish.

It was filmmaking at the edge of collapse. A brilliant, joyful, reckless circus balanced on the shoulders of a man who was gripping the tightrope with slipping fingers.

And somehow, the film kept moving forward.

The night the production nearly collapsed: Belushi and the skateboard

By the time the production moved from Chicago back to Los Angeles, the entire crew felt as if they had survived a military campaign. Chicago had given them car crashes, twenty hour days, and the constant question of whether the star would appear on set. Los Angeles, by comparison, seemed almost peaceful. The Universal lot felt familiar to everyone. Fewer street closures. Fewer city officials. Fewer stunt vehicles being welded back together in the middle of the night.

John Belushi also seemed, for a brief moment, steadier. He behaved politely in front of Ray Charles and Aretha Franklin. He avoided the heavy excesses that had slowed him in Chicago. He even joked that Los Angeles had “better oxygen.” Dan Aykroyd later said that these small periods of clarity often fooled the people who loved him. “John could summon his charm and his discipline when the situation demanded it,” he recalled. “Especially when he wanted to impress somebody. Especially musicians he respected.”

And then, without warning, the film came close to derailing again.

A simple request that changed everything

It was just before filming the climactic concert sequence at the Hollywood Palladium. This was the largest musical set piece of the entire film. Hundreds of extras. Elaborate choreography. Cameras placed on cranes, in rafters, and strapped to dolly tracks. Belushi and Aykroyd were required to perform energetic dance routines, flips, cartwheels and rehearsed stage moves. The entire finale depended on their physicality.

On the afternoon before shooting, Belushi stepped outside the Palladium and noticed a teenager gliding past on a skateboard. Belushi waved him over with a cheerful “Hey, buddy, let me try that.”

It was exactly the sort of impulsive act that defined him. In his mind, he was still the neighbourhood kid from Wheaton who played pranks and roughhoused with friends. Several people on the production later joked that Belushi lived his life as though he were still fourteen.

The teenager handed over the skateboard. Belushi stepped on, wobbled, and then fell with remarkable force.

Witnesses recalled hearing a heavy thud, followed by a low groan.

Belushi was clutching his knee.

The panic begins

Sean Daniel received the call first. His heart sank even before the assistant finished speaking. By this point in the production, any sentence containing the words “Belushi”, “injury”, or “you need to come down here” instantly triggered dread.

When Daniel arrived, he saw Belushi sitting on the floor, pale and sweating, teeth clenched. Bob Weiss, the producer, stood nearby trying to appear calm, though his face suggested a man watching his own house catch fire.

Daniel bent down and asked quietly, “How bad is it?”

Belushi grimaced. “It is bad,” he said. “I heard something pop.”

It was the worst possible moment for an accident. The finale was scheduled to begin filming the next morning. Extras had been booked. Musicians had been hired. The set had been lit and dressed. The schedule had no room for delay. Every hour cost a small fortune.

The forbidden name nobody wanted to say

Someone murmured, “Should we call Wasserman?”

Everyone paused.

Lew Wasserman did not receive bad news lightly. He had already endured months of rising budgets, missed days and spiralling costs. An injury to the lead actor on the eve of the finale would be the kind of report that could end the entire production.

Daniel later recalled thinking, “If I tell Lew that John Belushi cannot dance tomorrow, he will shut the film down. He will have every justification.”

But the situation required medical intervention, and only one person had the power to secure it at speed.

Wasserman.

Daniel took a breath, picked up the phone, and dialled the number he least wanted to dial.

Wasserman moves faster than anyone expected

When Daniel delivered the news, Wasserman did not ask how Belushi fell. He did not ask about skateboards, teenagers, or personal responsibility. He cut directly to the one question that mattered.

“Can he walk?”

Daniel hesitated. “Not at the moment.”

Wasserman exhaled through his nose. It was the closest he ever came to swearing.

“I will get the doctor,” he said. “You will keep him ready.”

Within half an hour, one of Los Angeles’s most respected orthopaedic surgeons arrived at the Palladium. He had been on his way to Palm Springs for a long weekend. Wasserman had politely informed him that his holiday would begin an hour later than planned.

The surgeon examined Belushi’s knee, pressed it gently, and winced before Belushi even reacted. “He should not be dancing on this,” the doctor said.

Daniel replied, “He has to.”

Wasserman had made that clear.

The needle, the wrap, and the impossible performance

After a brief consultation, the surgeon administered an anaesthetic injection directly into the joint. Belushi sucked in a sharp breath, swore twice, and then said, “All right, let’s do it.”

The knee was wrapped tightly. Belushi stood up with effort. Everyone watched to see whether he would collapse.

He stayed upright.

Then he tested his weight.

Still upright.

Someone clapped softly. Someone else whispered, “Thank God.”

Belushi walks on stage

The next morning, the extras filled the auditorium. Musicians tuned their instruments. Crew members whispered their doubts. Aykroyd looked at Belushi with concern. “Can you do this?” he asked.

Belushi gave a crooked grin. “I can do anything once.”

And he did.

He danced through the entire sequence. He performed the cartwheels. He delivered the energy the film required. No one watching the finished movie would ever suspect that the lead actor had nearly been incapacitated the day before. Aykroyd later said, “John was held together with tape and determination. That finale is him fighting through pain because he loved the film.”

For the crew, the relief was indescribable. They had survived another crisis. Another narrow escape. Another moment when the entire project almost came undone.

And yet, as many observed later, the accident was a symbol of the entire production. Brilliant. Chaotic. Dependent on one man whose body and spirit were being pushed far beyond their limits.

The show went on. But the cost was starting to show.

The fight for distribution and the theatres that said no

If the production stage felt like a battle, the fight to get The Blues Brothers into cinemas was something closer to a siege. After months of car crashes, rewrites, broken schedules and late night rescues, everyone assumed that the worst was finally behind them.

They were wrong.

The next storm arrived quietly. It came not from Wasserman, nor from the budget department, nor even from Belushi’s unpredictable stamina. It came from the theatre owners. In 1980, they were the true gatekeepers. They decided which films reached suburban audiences, which films were buried in midnight slots, and which ones played only in neighbourhoods that executives preferred to ignore.

John Landis understood the power dynamic clearly. “The exhibitors were the empire,” he said. “If they said no, the rest of us could go home.”

The disastrous preview screenings

Before the wide release, Landis organised a series of preview screenings for the owners of major theatre chains. These men were not creative risk takers. Most of them, as Landis put it, “wore white belts and white shoes,” which in Hollywood was code for conservative tastes and a suspicion of anything unusual.

The Blues Brothers was nothing if not unusual.

The film was long. The plot was chaotic. It mixed musical numbers with police chases, gospel sermons with absurdist comedy, and blues legends with a pair of comedians who looked like undertakers. No one had ever made anything like it. Some people found that thrilling. Others found it confusing.

One exhibitor cornered Landis after a screening and said bluntly, “I do not know what it is.”

Landis smiled. “It is a musical.”

The exhibitor shook his head. “Musicals do not blow up forty police cars.”

The second screening went even worse. A theatre owner leaned forward as the credits rolled and said, “Are those musicians in the film real? They look old.” He did not mean it kindly.

Ray Charles was a genius. Aretha Franklin was a powerhouse. James Brown had transformed American music. Cab Calloway had shaped an entire generation of performers. But in 1980, some exhibitors considered them outdated. Too black. Too old. Too rooted in a cultural tradition they did not understand.

One man even asked, “Could you cut the songs and make it a tighter comedy?”

Landis stared at him in disbelief. “The songs are the film,” he said.

The meeting with Ted Mann that changed everything

The worst encounter came when Lew Wasserman summoned Landis to his office for an early morning meeting. Waiting for him was Ted Mann, the powerful head of Mann Theatres, which controlled some of the most desirable cinemas in the western United States.

According to Landis, Mann opened the conversation with a sentence so blunt that even Wasserman lifted an eyebrow.

“Mr Landis,” Mann said, “we will not book The Blues Brothers in any of our major theatres.”

Landis asked, “Why?”

Mann replied, “Because I do not want black patrons coming to Westwood.”

Silence. Heavy. Embarrassed. Infuriating.

Landis later said, “It was the most openly racist thing I had ever heard in a business meeting.” Mann tried to justify his decision by saying that white audiences would not buy tickets for a film full of older black musicians. He said they would only play the film in Compton, and perhaps a few other neighbourhoods that were, in his words, more appropriate.

Wasserman listened without expression. He did not rebuke Mann. That was not his way. He simply nodded, dismissed him, and turned back to Landis. “Cut the film,” he said. “Make it shorter.”

It was the closest he would come to admitting how precarious the situation had become.

A shrinking release that felt like sabotage

A typical large studio film in 1980 opened in approximately fourteen hundred cinemas. The Blues Brothers secured fewer than six hundred. More than half the country would not see the film in its first wave of release.

Executives considered this a near guarantee of financial failure. Belushi knew it too. According to friends, he spent his evenings driving from cinema to cinema in New York, slipping into auditoriums to listen to the audience. He needed to know whether they were laughing. Whether they were clapping. Whether they understood what he and Aykroyd had fought so hard to build.

Aykroyd watched the film in a cinema in Times Square. He later said, “I sat in the back row and listened. The laughter came like little sparks. Then bigger ones. People got it.”

Studio executives still predicted a flop.

The critics sharpen their knives

The early reviews did not help. Some critics praised the performances but complained about the length. Others called the plot a mess. One writer described it as “a ponderous comic monstrosity.” Another declared that “the cars act better than the actors.” The Washington Post lamented the film’s scale, complaining that the car chases were shot too seriously. Janet Maslin of The New York Times wrote that the film never explained why Jake and Elwood loved black music, as though art requires footnotes.

Gene Siskel, however, called it “one of the greatest comedies ever made.” Roger Ebert admired its energy and “unexpected moments of grace.” But the divide between critics only fuelled Universal’s anxiety.

The night everything changed

The weekend of release finally arrived. The numbers began to come in. At first they trickled. Then they accelerated. Then they exploded.

Crowds were lining up.

Audiences were cheering.

Kids who had never heard Cab Calloway were humming Minnie the Moocher in the lobby. People were dancing out of the cinema after James Brown’s sermon. Teenage boys tried to imitate Belushi’s cartwheels. Middle aged men in sunglasses walked down the street shouting, “We are on a mission from God.”

The exhibitors who had refused the film panicked. Suddenly they wanted it. They wanted it everywhere.

The Blues Brothers went on to make more than one hundred and fifteen million dollars worldwide. It sold out cinemas in Europe. It earned more overseas than in America, becoming one of Universal’s biggest international hits.

Landis later said, “The people who were supposed to know what audiences wanted were completely wrong. And the audiences were completely right.”

The film had survived everything. Budgets. Chaos. Drugs. Racism. Executive doubt. The near collapse of its own star.

Yet it was still standing.

Just like Jake and Elwood.

A cult is born and the legends are reborn

In the months after its release, something strange happened. Something no studio executive had predicted despite the shouting, the budgets, or the chaos of the set.

The Blues Brothers refused to fade.

It did not behave like a typical Hollywood comedy. Rather than disappearing after a few weekends, it kept returning. People went back to see it again and again. College students memorised lines, sometimes entire scenes. Music fans who had never cared for comedy films embraced it as a revival of American soul. Children who were too young to appreciate the references grew up quoting it anyway.

The film had entered that rare space where something becomes larger than the intentions of its creators.

John Landis put it simply. “We thought we were making a comedy. Audiences turned it into a ritual.”

The revival nobody saw coming

One of the most remarkable and least discussed outcomes of the film was the revival of its musical cast. At the time of filming, Ray Charles was still respected but no longer charting regularly. Aretha Franklin had found the late 1970s difficult, her albums selling modestly compared with her earlier triumphs. James Brown’s career had cooled. Cab Calloway, though still performing, had long passed his commercial peak.

Then the film arrived.

Sales of Ray Charles albums increased. Aretha Franklin’s number Think experienced a second life. People discovered James Brown for the first time or rediscovered him anew. One radio programmer said in 1981, “You could draw a line between the release of the film and the sudden renewed demand for these artists.”

Cab Calloway told a reporter, “I did not expect that singing Minnie the Moocher in a white suit again would make people remember me. But those young people cheered. They cheered like it was 1935. Bless those Blues Brothers.”

Ray Charles joked that he loved the film because it allowed him to show people that he could still hit a keyboard with the force of a man half his age. Aretha Franklin was more direct. “My scene in that diner,” she said, “that was the real me. Attitude. Rhythm. And that wig.”

Screenings that became events

By the mid 1980s, late night cinemas discovered something unusual. Whenever they scheduled The Blues Brothers at midnight, audiences arrived in costume. People wore black suits, hats and sunglasses. They shouted the lines before the actors delivered them. They clapped along with Minnie the Moocher and shouted Hallelujah during James Brown’s sermon.

It had become a social event.

In Australia, the Valhalla Cinema in Melbourne turned it into a regular communal ritual. People danced in the aisles. They sang. They brought harmonicas. Landis later said, “I never expected Australians to turn my film into a nightclub, but they did, and I loved them for it.”

The film’s sense of community became part of its identity. It attracted musicians, misfits, students, nostalgic adults and teenagers who had no idea what a Dodge Monaco was but desperately wanted one.

The afterlife of Jake and Elwood

What surprised people most was that the characters themselves grew into cultural icons independent of the film. There were Jake and Elwood posters, T shirts, toy cars, tribute bands and impersonators. Couples dressed as the brothers for parties and weddings. One bar became known for offering free drinks to anyone who could perform the dance from the Aretha Franklin scene.

Dan Aykroyd never claimed ownership of the phenomenon. “Jake and Elwood belong to the people,” he said. “They took them and ran.”

Even the Catholic references in the film attracted unexpected admiration. In 2010, the Vatican’s official newspaper praised the film for its moral themes of redemption, loyalty, and perseverance. Aykroyd reacted with typical humour. “When the Vatican calls your movie Catholic, you know you have done something unusual.”

The long shadow of Belushi

The film’s success was bittersweet for many who had worked on it. Less than two years after the premiere, John Belushi died at the Chateau Marmont. He was thirty three. The public mourned the loss of a remarkable comic voice. His friends mourned something more intimate.

Aykroyd once reflected, “The Blues Brothers was John at his best. Not the chaos. Not the drugs. The joy. The music. The humanity. That was the real John.”

Many fans believe the film preserves a version of Belushi that felt larger than life and yet deeply human. One minute a thunderbolt of energy leaping across a stage, the next a quiet man who loved fries and Frank Zappa records.

Landis later said, “When I watch the film now, I see him alive again. That is the magic of cinema. We get to see our friends again.”

A legacy written in sunglasses and soul

The Blues Brothers remains one of the most unusual studio successes in film history. A film too long. Too expensive. Too chaotic. Too strange. A film that executives predicted would fail. A film that theatres refused to book. A film that cast the legends of soul at a time when their careers had stalled.

Yet it became a global hit. It revived musical icons. It created a cult. It introduced a new generation to the power of the blues.

And after all the panic, all the studio concerns, all the arguments about casting, length and budget, the film proved one thing beyond all doubt.

A mission from God never needed approval from the numbers men.

Sources

Aykroyd, Dan. Dan Aykroyd: Newsweek Interview Archive

Belushi Pisano, Judith and Tanner Colby. Belushi: A Biography

ISBN 9781608870272

Belushi Pisano, Judith. Samurai Widow

ISBN 9780385413256

Landis, John. Monsters in the Movies (contains interview material on The Blues Brothers)

ISBN 9780756651978

Reitman, Ivan and Landis, John. The Blues Brothers: An Oral History (collected interviews, originally run in Vanity Fair and supplemental material)

Sobel, Jon. The Blues Brothers: A Cultural History (academic title on film context and music revival)

ISBN 9781442269867

Murphy, Donnie. Downchild: Fifty Years of Blues (Downchild Blues Band history with anecdotes about Belushi and Aykroyd)

ISBN 9781770415556