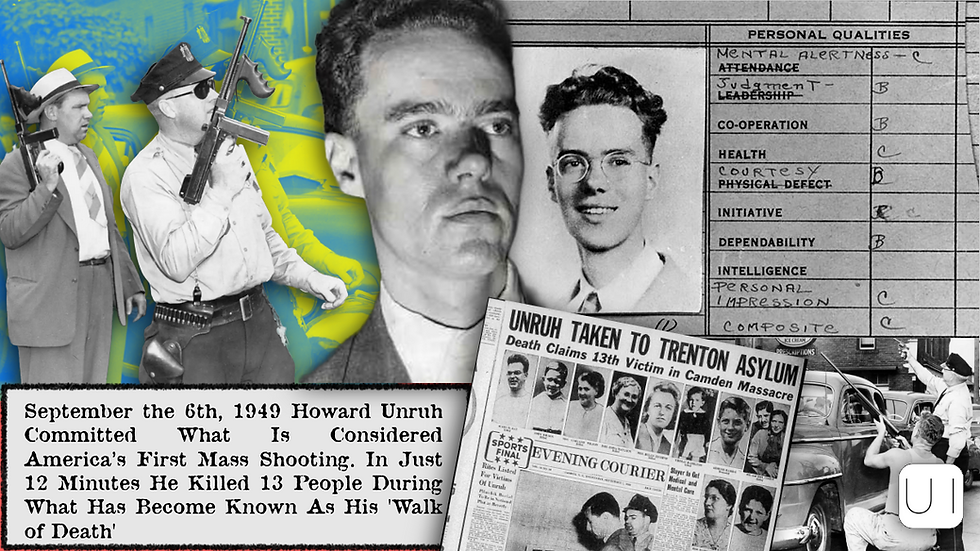

Howard Unruh and the Walk of Death: America’s First Modern Mass Shooting

- Anna Avis

- Sep 6, 2025

- 7 min read

On the morning of 6 September 1949, in a quiet neighbourhood of Camden, New Jersey, an ordinary day turned into something unthinkable. A shy, 28-year-old war veteran named Howard Unruh left his apartment with a German Luger pistol and, in just twelve minutes, killed thirteen people as he walked down River Road.

Later called the “Walk of Death”, the incident shocked post-war America. The country had seen violence before, but this felt different, random, sudden, and terrifyingly modern. Decades before the words “mass shooting” became part of everyday vocabulary, Howard Unruh was already living out what would become a dark and recurring pattern in U.S. history.

Unruh himself put it chillingly after his capture:

“I’d have killed a thousand if I had enough bullets.”

This is the story of Howard Barton Unruh, his troubled life, his fateful twelve minutes of violence, and the six decades he spent behind locked doors until his death in 2009.

The Troubled Life of Howard Unruh

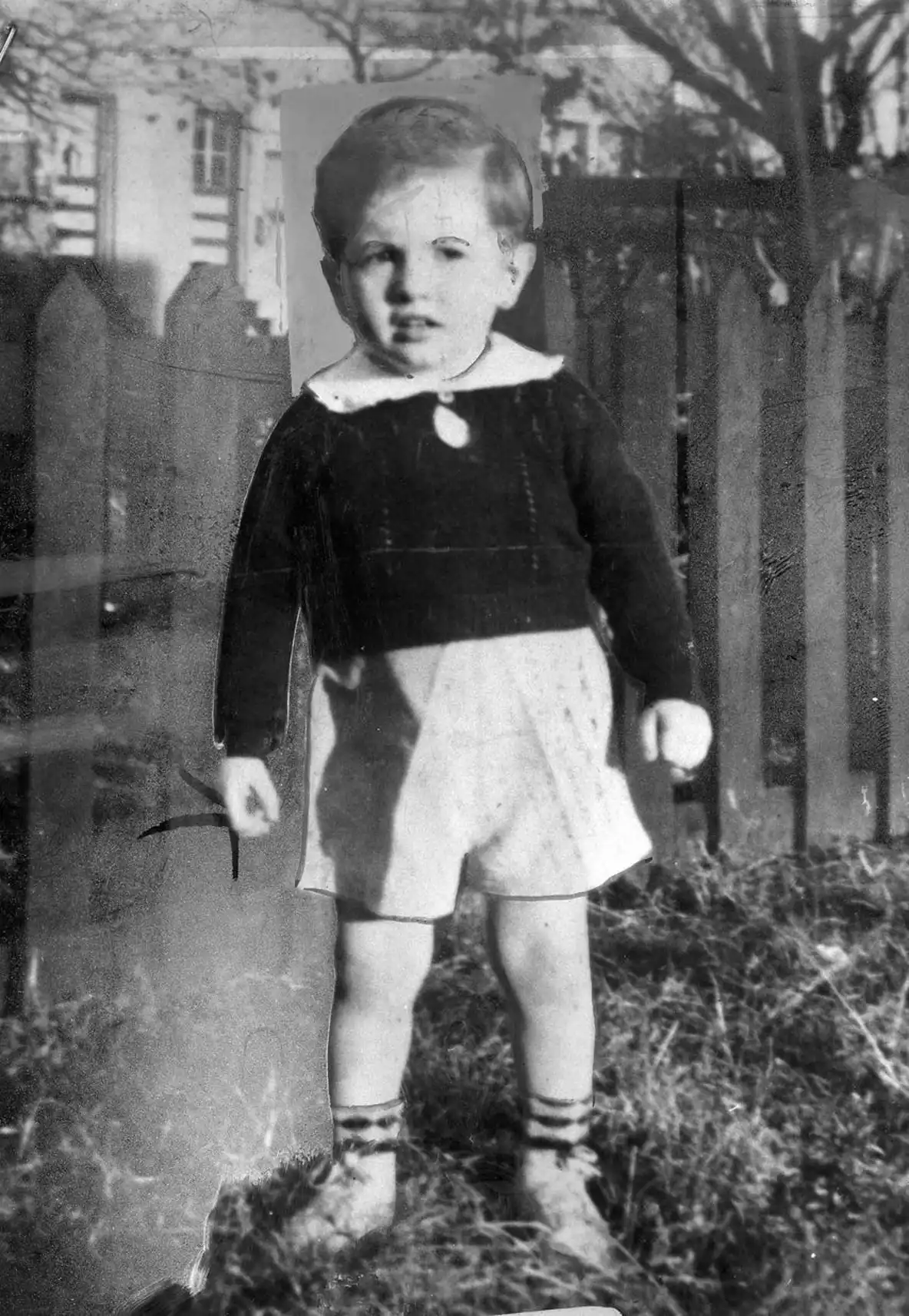

Howard Unruh was born on 21 January 1921 in Camden, New Jersey, to Samuel Shipley Unruh and Freda Vollmer. His parents’ marriage did not last, and he and his younger brother James were raised largely by their mother.

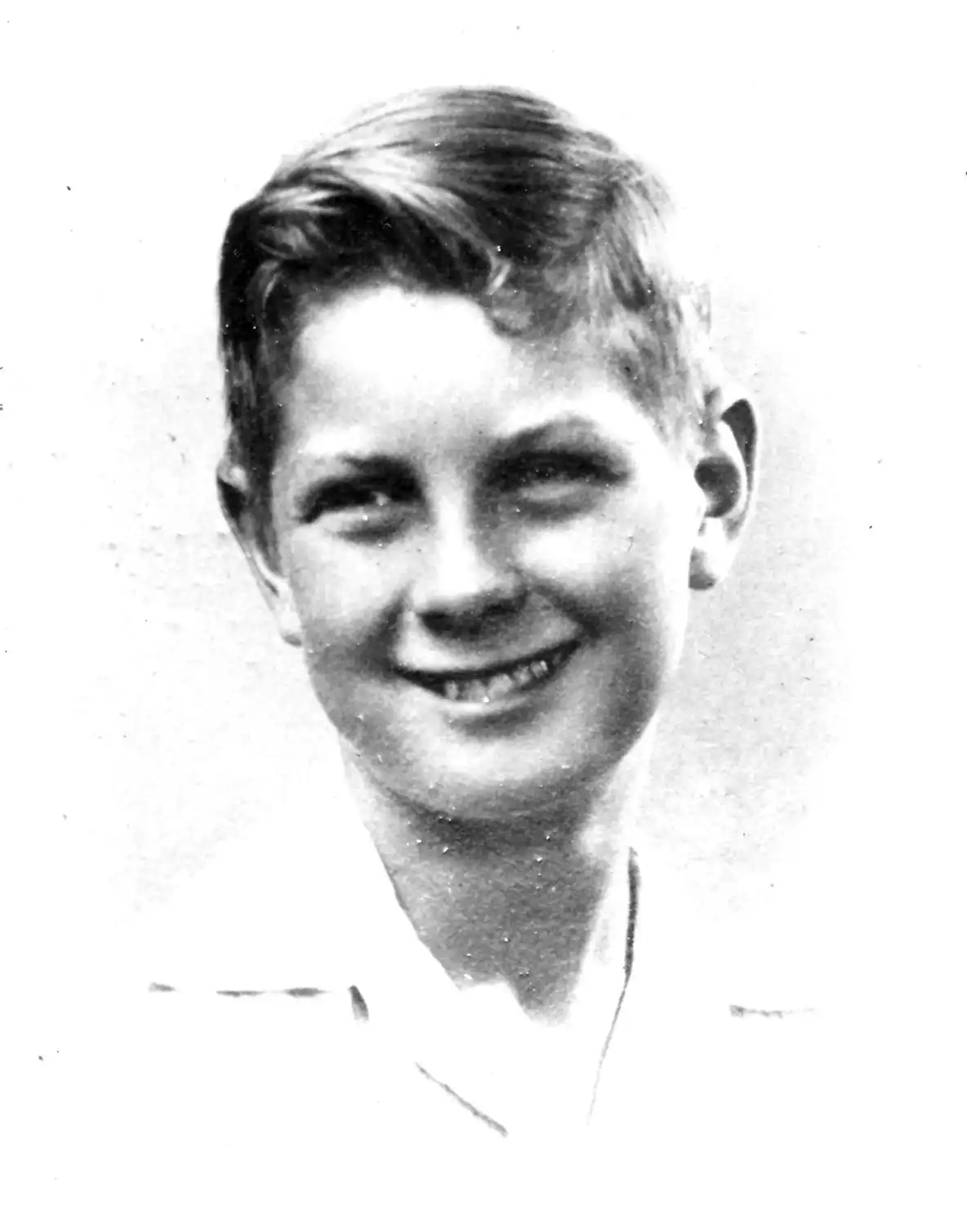

Those who knew Howard as a boy described him as quiet, shy, and solitary. His 1939 high school yearbook at Woodrow Wilson High even noted his ambition to become a government employee, hardly a grand dream, but it suited the mild-mannered young man.

After graduation, Unruh drifted. He tried working as a sheet-metal labourer, then briefly enrolled at Temple University’s School of Pharmacy in Philadelphia. But he dropped out after just a month, citing poor health.

Instead, he lived with his mother, decorating their home with his war medals, reading his Bible, and retreating into his basement, where he built a makeshift shooting range. That detail alone feels like an ominous foreshadowing.

Soldier and Survivor

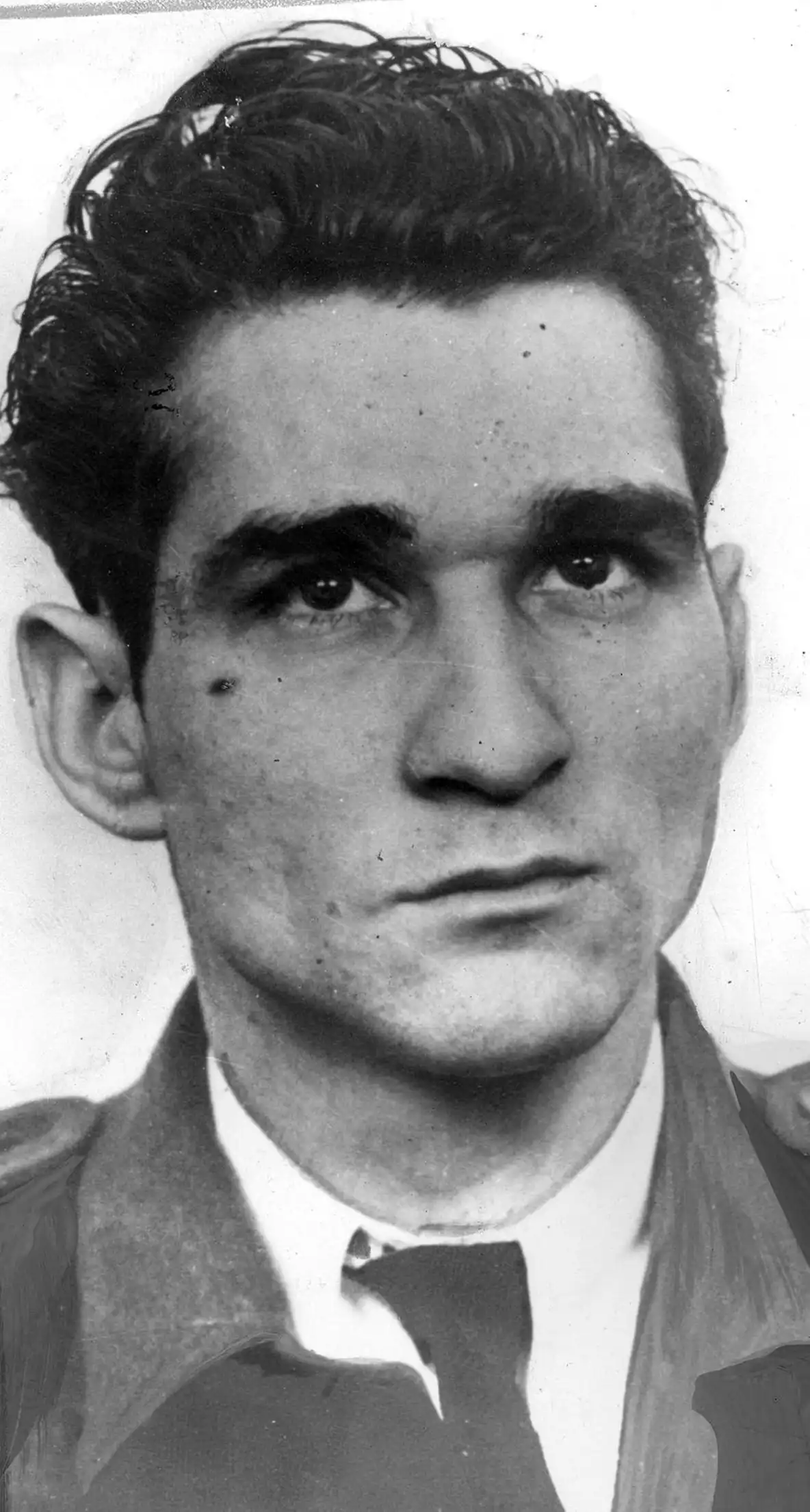

In 1942, at the age of 21, Unruh joined the U.S. Army. He served as a tank gunner in the European theatre of World War II. By all accounts, he was an excellent marksman and a disciplined soldier. His superior, Norman Koehn, remembered him as a man who never drank, swore, or chased women.

But beneath the surface, something was unsettling. Unruh kept a meticulous diary of the people he killed in battle. He noted not only the date and time but the state of their bodies. This obsession with detail hinted at a disturbing fascination.

When he returned home in 1945, family and neighbours noticed a change. He was moody, withdrawn, and suspicious. James, his brother, later said, “The war made him nervous and jumpy. He was never the same again.”

Growing Resentments

By the late 1940s, Unruh’s life had stalled. Living off his mother’s modest factory income, he rarely worked and instead nurtured grudges against neighbours.

He felt people disrespected him, whispered about him, and laughed at him behind his back. Some of these slights were real, Maurice Cohen, a pharmacist who lived below Unruh’s flat, reportedly called him a “queer”, while others were imagined.

Unruh kept a list of names, grievances, and insults, tallying who had wronged him. It was the start of what would later become his “kill list.”

The Trigger

On the night of 5 September 1949, Unruh went into Philadelphia for a late-night film date with a man he had been seeing. When he arrived, the man had already left. By the time he got home, Unruh discovered that the gate he had recently installed, a sore point in his feud with the Cohens, had been vandalised.

That was the final straw. He decided tomorrow would be the day of reckoning.

The Walk of Death

At 9:20 a.m. on 6 September 1949, Howard Unruh walked out of his apartment armed with his 9mm Luger pistol and extra magazines. His first shot was aimed at a bread delivery driver, who managed to escape. From there, the killings came one after another.

He shot shoemaker John Pilarchik (27) in his shop.

He killed barber Clark Hoover (45) in his chair, and six-year-old Orris Smith, who was getting his hair cut while perched on a carousel horse.

Insurance man James Hutton (46) crossed his path and was gunned down.

At the Cohen pharmacy, Unruh targeted his long-time adversaries. Rose Cohen (38) was found hiding in a closet and killed. Her mother-in-law, Minnie Cohen (63), was shot while attempting to call the police. Pharmacist Maurice Cohen (39) tried to escape onto the roof, but Unruh shot him in the back, sending him tumbling onto the pavement below.

The rampage spread into the street. Alvin Day (24), a driver in a passing car, was killed instantly. Helga Zegrino (28), the wife of a tailor Unruh held a grudge against, was murdered in her shop.

At an intersection, Helen Wilson (37) and her mother Emma Matlack (68) were killed in their car. Helen’s son, John Wilson (9), later died of his wounds in hospital.

Finally, in one of the most haunting moments of the Walk of Death, Unruh fired into an apartment window and killed two-year-old Thomas Hamilton, who had been playing inside.

By the end, thirteen people were dead and three more were injured, including Madeline Harris and her son Armand, who survived despite gunshot wounds.

The Phone Call in the Middle of the Siege

As police surrounded Unruh’s apartment, a journalist named Philip Buxton did something extraordinary. Looking up Unruh’s phone number in the directory, he rang him. To his surprise, Unruh picked up.

“Is this Howard?” Buxton asked.

“Yes … what’s the last name of the party you want?” Unruh replied.

When Buxton pressed him on why he was killing people, Unruh chillingly said:

“I don’t know. I can’t answer that yet, I’m too busy.”

The conversation ended with gunfire in the background. It remains one of the eeriest moments in crime reporting.

Camden Reacts

The community of Camden was left reeling. River Road had been a friendly stretch of shops and homes. Suddenly, it was a crime scene.

Witnesses collapsed in shock. A neighbour, Irene Rice, fainted after seeing young Tommy Hamilton shot. Parents described how their children became frightened of barbershops after the murder of little Orris Smith.

The Camden Evening Courier filled its pages with details of funerals and grief. Churches overflowed with mourners. For weeks, residents looked over their shoulders, shaken by the knowledge that their own neighbour, quiet Howard Unruh, had unleashed such horror.

National newspapers branded it “a massacre on River Road,” and the Walk of Death became one of the first widely reported mass shootings in America.

Arrest and Confinement

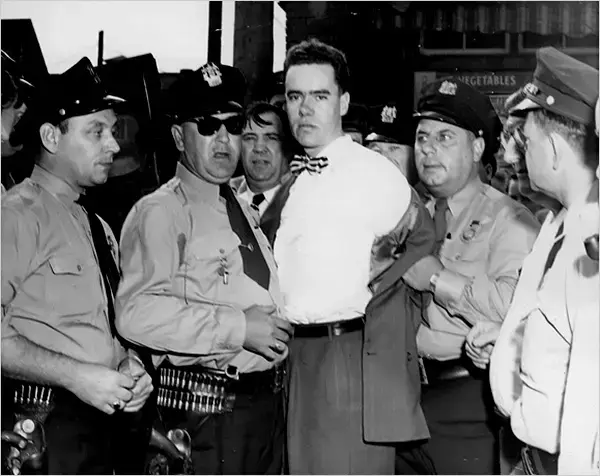

The standoff ended when police fired tear gas into Unruh’s flat. He surrendered, limping with a gunshot wound to his leg.

Police later found his apartment stacked with weapons, ammunition, and shooting targets. On a table, his Bible lay open to the Book of Matthew, Chapter 24, a passage about judgement.

Unruh was charged with thirteen counts of murder. But he never stood trial. Psychiatrists diagnosed him with paranoid schizophrenia, and he was declared criminally insane. He was sent to the Trenton Psychiatric Hospital, where he would remain for the rest of his life.

Six Decades in Confinement

For sixty years, Howard Unruh lived in near-total obscurity in a psychiatric cell. He gave occasional interviews, sometimes showing flashes of remorse, sometimes cold detachment.

“Murder’s a sin,” he once admitted, “and I should get the chair.”

But more often, his words echoed the same detached cruelty of that September morning. At one point, he reportedly said:

“I’d have killed a thousand if I had enough bullets.”

Unruh died in 2009 at the age of 88.

Legacy of the Walk of Death

Howard Unruh’s killings remain the deadliest mass shooting in New Jersey’s history. More importantly, many historians see them as the first modern American mass shooting, a template of random, indiscriminate violence by a lone gunman.

Since then, mass shootings have tragically become a recurring event in American life. From university campuses to shopping centres, workplaces to schools, the echoes of Camden in 1949 are still felt.

By remembering the victims, not just the man who killed them, we place the tragedy of 1949 where it belongs: in the lives cut short and the families torn apart.

Final Thoughts

The story of Howard Unruh is a grim milestone in American history. What makes it even more haunting is how modern it feels. The Walk of Death wasn’t just a local tragedy in Camden; it was a warning of what was to come.

Seventy-five years later, the questions remain. What makes someone like Howard Unruh cross that line? Could his life have gone differently with proper care, community, or intervention? Or was his Walk of Death always waiting to happen?

Whatever the answers, the name Howard Unruh will always be linked to the origins of mass shootings in America — and to the reminder that, in his own chilling words, “I don’t know yet, I’m too busy.”

Sources

Mel Ayton, Hunting Howard Unruh: America’s First Mass Murderer (Arcturus, 2022)

David M. Kennedy, Crime and Punishment in America (Vintage, 1998) – includes early analysis of Unruh’s case in the context of modern mass shootings

Ralph S. Banay, Psychiatry and the Law (1950) – early psychiatric discussions of Unruh’s trial and diagnosis

Camden Evening Courier (September 6–9, 1949 editions) – first-hand reports and photographs of the Walk of Death

The New York Times, “13 Dead in Camden as War Veteran Runs Amok” (7 September 1949)

Life Magazine, Ralph Morse’s photographs, “Walk of Death” feature (September 1949 issue)

The Philadelphia Inquirer, coverage in the days following the shootings

FBI Records Vault – Howard Unruh file (FBI FOIA release)

Smithsonian Magazine, “Howard Unruh and America’s First Mass Shooting”

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/americas-first-mass-shooting-Howard-Unruh-180972194/

The New York Daily News archive, “The Walk of Death in Camden, NJ” (1949 retrospective)

South Jersey History Project – Camden County Historical Society archives on the Walk of Death

Associated Press obituary of Howard Unruh (2009), widely syndicated

PBS NewsHour, “The Origins of the Modern Mass Shooting” (includes Unruh’s case as a starting point)

NJ.com (Star-Ledger), “Remembering the Walk of Death: Howard Unruh’s 1949 Rampage”

Comments