Emma Willard and Her Beautiful Historical Time Maps

- Daniel Holland

- Jun 12, 2025

- 6 min read

In the mid-19th century, at a time when the United States was rapidly expanding its borders and solidifying its national identity, a singular figure emerged who was as much cartographer as she was educator, and as much propagandist as she was innovator. Emma Willard, born in 1787 just a few years after the American Revolution, was part of the first generation of American women to receive formal education beyond the domestic sphere. She would go on to become one of the most influential female educators and educational publishers of her century, and arguably, one of its most important visual thinkers.

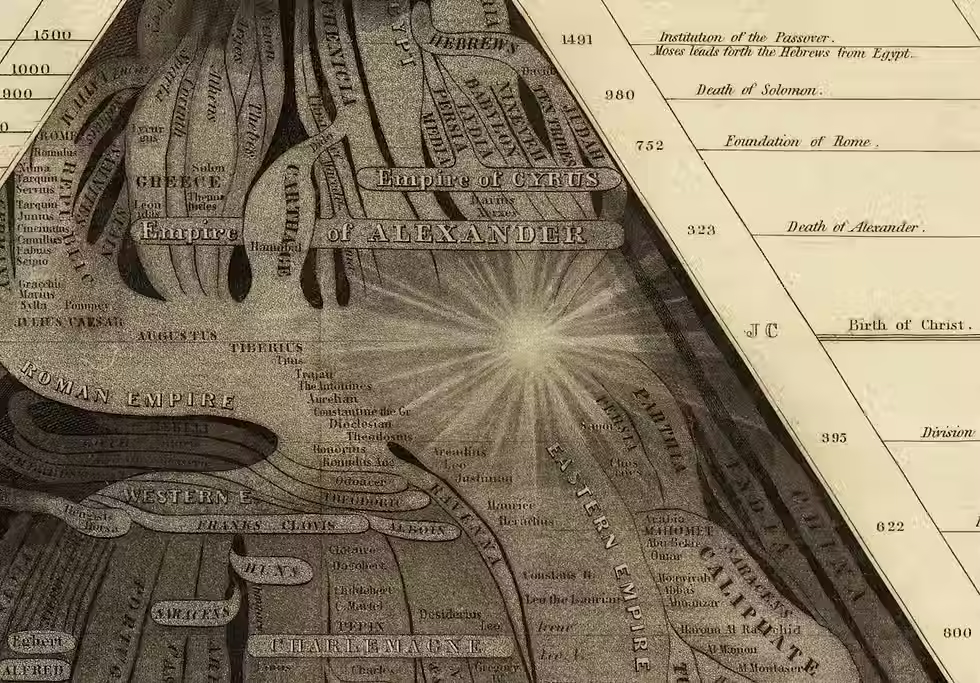

Today, our screens are saturated with infographics and maps, translating the chaos of daily data into digestible formats. In many ways, Emma Willard anticipated this visual age. Her maps were not merely geographical: they were attempts to chart time, to make history visible, structured, and legible. From her “Perspective Sketch of the Course of Empire” (1835) to her ornate “Temple of Time” and finally her “Tree of Time,” Willard reimagined the past as something that could be entered, explored, and understood — spatially.

The Age of Visual Learning

The early 1800s saw an explosion of educational innovation. With new printing technologies came new possibilities: illustrated textbooks, wall maps, and school atlases filled classrooms from the eastern seaboard to the growing western frontier. Education expanded to include not just the sons of merchants and landowners, but the daughters of farmers and newly arrived immigrants. It was in this highly competitive and rapidly evolving market that Emma Willard made her name.

Her early experiences with inadequate geography textbooks led her to encourage students to redraw maps from memory — an effort to internalise spatial relationships and political history. This pedagogical experiment marked the beginning of her obsession with making information visual. Willard believed the visual preceded the verbal. She argued that young learners, especially girls, benefited more from striking illustrations and imaginative layouts than dry chronological tables or rote memorisation.

Inventing the Map of Time

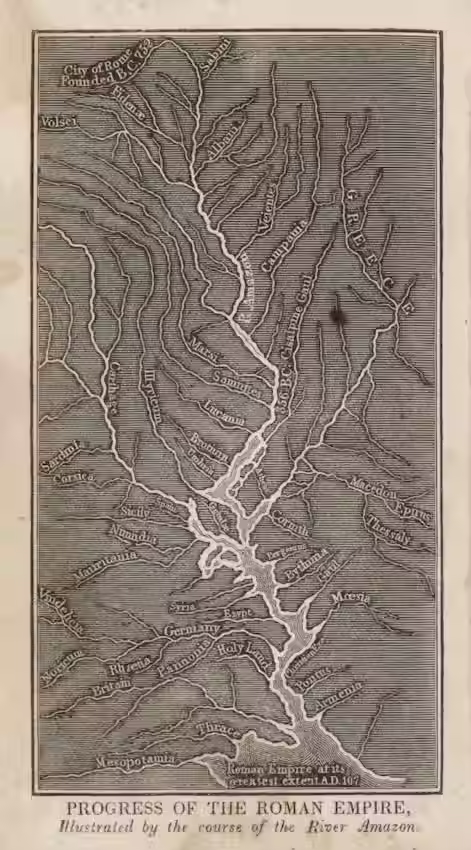

In 1835, Willard published her “Perspective Sketch of the Course of Empire,” a dramatic reimagining of historical time. It took the form of a sloping landscape, with Biblical Creation perched at the summit and successive empires — Babylon, Persia, Greece, Rome, and so on — flowing down toward the present. The timeline widened as it neared the viewer, giving students the sense that time became more relevant and vivid as it approached their own age.

This use of perspective was radical. Inspired partly by Enlightenment attempts to chart human development (such as Joseph Priestley's 1765 Chart of Biography), Willard added a third dimension. The birth of Christ, for example, appeared as a radiant flash of light, dividing ancient from modern history. Civilisations were situated not by geography, but by their relative cultural influence and interactions. The goal was not accuracy in the modern cartographic sense but rather mnemonic resonance: to help students visualise civilisational succession, influence, and the march of progress.

Willard described time not as linear but dimensional — a stream widening with each successive age. In her view, time had accelerated, especially with steam and rail transport redefining pace and perception in the 19th century. Traditional timelines failed to capture this sense of quickening. Her “Course of Empire” became a bestseller in classrooms across the country.

The Temple of Time: A Memory Palace for the Nation

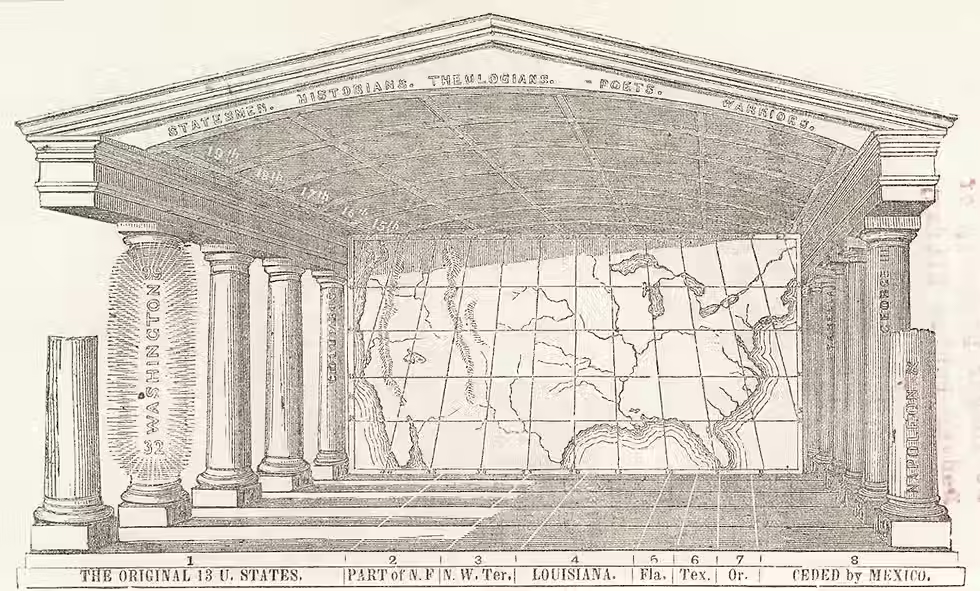

By the 1840s, Willard had refined her ideas further. Her “Temple of Time,” perhaps her most ambitious visualisation, combined chronology and geography in a single, neoclassical architectural metaphor. In this image, time flowed along the temple floor like a river. Columns lining the nave marked out centuries, and inscriptions on each pillar identified the era’s most notable poets, generals, and rulers.

Students were no longer merely observers of history but participants. They were invited into the temple, to “stand” in different historical epochs, effectively turning education into an immersive experience. Willard likened this visual system to cartography itself. Just as a flat map of a mountainous country relied on symbols, lines, and proportional spacing to convey reality, her Temple of Time transformed the abstract concept of duration into something spatially graspable.

She wrote, “It is as scientific and intelligible to represent time by space, as it is to represent space by space.”

This was more than metaphor — it was a pedagogical principle. Willard's method aimed to help learners situate themselves in history and feel the weight of its continuity.

Visualising American Destiny

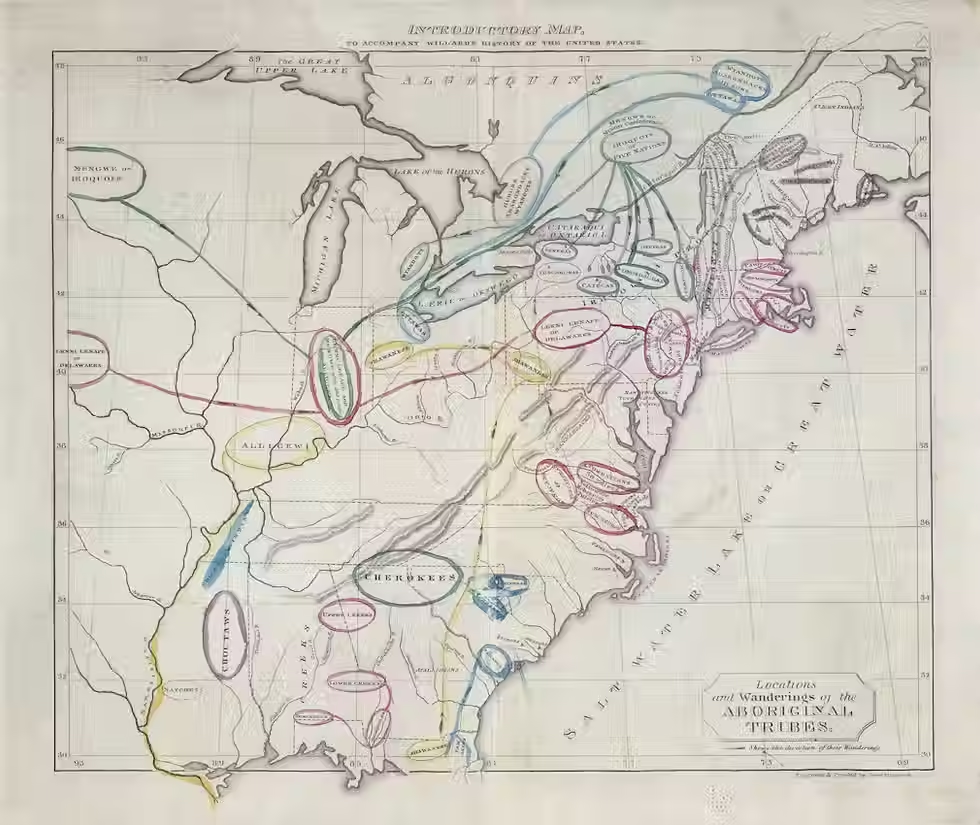

As her historical focus turned toward the United States, Willard’s maps became more overtly nationalistic. In 1828, she had published History of the United States, or Republic of America, the first historical atlas of the country. The accompanying maps marked out key events in the shaping of American identity — Plymouth Rock, the Treaty of Paris, the War of 1812. But notably, her “introductory map” traced the migration of Indigenous tribes across North America, collapsing centuries of movement and displacement into a single image.

This visual simplification cast Native Americans as a prelude to the real drama of history — the rise of European settlement and the birth of the American nation. Historian Susan Schulten has noted that Willard, though progressive in some respects, was an “exuberant nationalist” who viewed the westward expansion of Anglo-American settlers as both inevitable and righteous. Her maps rendered Indigenous presence and removal as abstract, inevitable flows, rather than as events involving profound suffering and resistance.

Her later “American Temple of Time,” created in the wake of the 1848 annexation of former Mexican territory, reinforced a doctrine of Manifest Destiny. Students were asked to shade regions of the United States — from the original 13 colonies to Oregon, Texas, and the recently acquired Southwest — in order to visualise the nation’s territorial expansion over time. This was a hands-on, visual reinforcement of national cohesion, power, and historical mission.

The Tree of Time

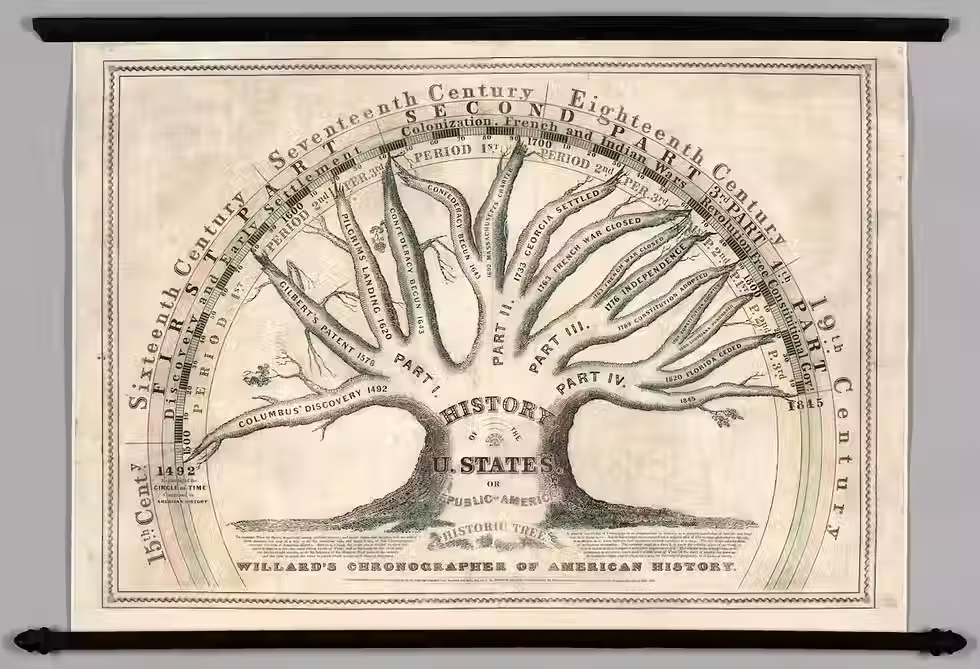

By the 1850s, Willard distilled her visual thinking into her most straightforward and organic metaphor: the “Tree of Time.” While trees had long symbolised genealogy, Willard used this form to map the growth of the United States. Unlike traditional family trees that extend vertically, her Tree of Time flowed left to right, in the fashion of a modern timeline. American history, from 1492 to the present, branched out as an ordered and coherent story of progress.

She used this illustration to introduce every new edition of her History of the United States, and even produced large versions for schoolroom walls. Again, the underlying message was clear: the United States was the culmination of a centuries-long process — the fruit of ancient empires, medieval kingdoms, colonial endeavours and revolutionary ideals.

The Limits of the Vision

Yet there was a curious silence in Willard’s visual language when it came to civil discord. Her Tree of Time, updated periodically, did not reflect the secession of Southern states or the outbreak of the Civil War, which was already underway when she issued its final edition. The last marked date on the tree was 1860, just as the nation fractured. Willard’s accompanying text led readers to the brink of war — and stopped. The harmonious story she had built, branch by branch, was no longer sustainable. History itself had overtaken the narrative.

Legacy

Emma Willard’s contributions to education extended far beyond her maps. She founded the Troy Female Seminary in 1821, one of the first institutions in the United States to offer young women a curriculum equal in rigour to that of their male counterparts. Her belief in female intellectual capacity was unwavering. She published numerous textbooks, gave public lectures, and corresponded with political leaders on the importance of women’s education.

Yet it is her visual work, her cartographic imagination, that remains most compelling today. In an age awash with information, her impulse to make the abstract tangible feels remarkably modern. Whether by temple, stream, or tree, Willard sought to help students not just learn history but inhabit it.

She didn’t just teach time. She mapped it.

Comments