The Tragic Death Of Virginia Rappe And The Trials Of Fatty Arbuckle

- Daniel Holland

- Sep 20, 2025

- 10 min read

The laughter stopped almost overnight. One long weekend in San Francisco in September 1921 turned the most bankable comedian in the world into a cautionary tale for the entire motion picture industry. It is a story of a party in a hotel suite, a young actress in agony, a media storm so fierce it scorched reputations, and three trials that ended not with a simple acquittal but with a written apology from a jury. More than a century later, people still argue about what really happened to Virginia Rappe and why Roscoe Fatty Arbuckle never truly recovered.

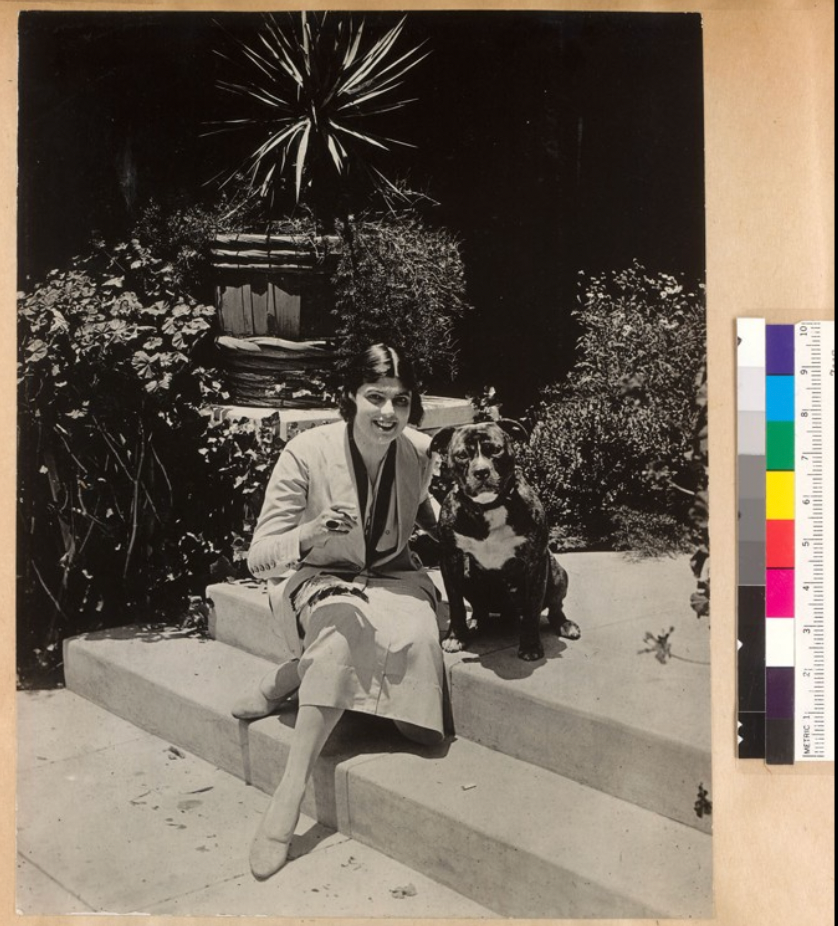

Virginia Rappe before the headlines

Long before the photographs of the funeral and the court stenographers’ pages, there was a determined and imaginative woman. Virginia Rappe was born in Chicago on seven July eighteen ninety one. Her mother died when Virginia was eleven, and she was raised by her grandmother. As a teenager she modelled in department store fashion shows and became one of the earliest models to support herself from the new profession. Articles presented her as a modern woman who urged readers to be original and even posed in tuxedos for a piece calling for equal clothes rights for women.

This is all the footage that remains of a movie starring Rudolph Valentino and Virginia Rappe. The plot, such as it is, includes three men caught up in a revolution. The movie was later recut and reissued to take advantage of Valentino's superstar status and Rappe's tragic death.

By nineteen fourteen she was designing garments and had work associated with the great exposition year of nineteen fifteen. Silent pictures followed. Rappe appeared in a little over a dozen titles, including Paradise Garden, and she found steady work in Los Angeles with director Fred J Balshofer. By nineteen nineteen she was in a relationship with filmmaker Henry Lehrman and the pair were engaged at the time of her death. There had been sadness too. In San Francisco she had briefly been with dress designer Robert Moscovitz, who died in a trolley car accident. Through it all she sustained a public image that blended independence, style, and what newspapers liked to call modern ideas.

Arbuckle at the top

Roscoe Arbuckle was one of the most popular stars of the silent era. Posters joked that he was worth his weight in laughs and audiences loved the surprising lightness of his movement. In nineteen twenty one he signed a one million dollar deal with Paramount, a sum that startled the business. His feature Crazy to Marry had just opened. Despite suffering second degree burns to both buttocks during an on set mishap, Arbuckle took a holiday weekend drive to San Francisco with friends Lowell Sherman and Fred Fishback. They checked into the St Francis Hotel. Room twelve twenty one for Sherman. Room twelve nineteen for Arbuckle and Fishback. Room twelve twenty reserved as the party room.

Prohibition did not slow anyone down. Bootleg liquor flowed in the suite, along with the usual chatter of producers, models, and aspirants. Virginia Rappe arrived with friends including Bambina Maude Delmont. The party ebbed and surged. Music drifted out of open doors. Then the mood shifted.

The incident in room twelve nineteen

During the carousing, Rappe became violently ill. The hotel doctor concluded that intoxication was the main problem and administered morphine to calm her. She was not admitted to hospital until two days later. On Friday nine September nineteen twenty one she died of peritonitis caused by a ruptured bladder.

Delmont told police that Arbuckle forced Rappe into room twelve nineteen, allegedly saying I have waited for you five years and now I have got you. Delmont claimed she heard screams from behind the door, that Arbuckle opened it with what she called a foolish smile, and that Rappe lay on the bed in pain. Delmont said Rappe managed to say Arbuckle did it. At a press conference, Rappe’s manager added a lurid detail, asserting that Arbuckle had used a piece of ice to simulate sex. By the time newspapers rehearsed the tale, the ice had become a bottle. Witnesses present at the party later testified that ice was rubbed on Rappe’s stomach to ease cramps. The examining doctor found no evidence of sexual assault.

Arbuckle denied wrongdoing. His early public account insisted he was never alone with Rappe. His sworn testimony corrected that. He said he found her in his bathroom vomiting, helped her onto a bed, asked others to assist, and when her condition appeared to settle he drove another guest into town. No one disputed that Rappe was in distress. The question that consumed the city was why.

Arrest and the new power of the press

The day after Rappe’s death, police arrested Arbuckle and he was arraigned without bail. A grand jury soon indicted him on first degree manslaughter. The San Francisco district attorney, Matthew Brady, was an ambitious figure who made public pronouncements of Arbuckle’s guilt and pressured witnesses to embellish. Newspapers were ravenous. William Randolph Hearst later boasted that the Arbuckle scandal had sold more papers than when the Lusitania went down. That one line explains the fever. Headlines hardened into judgement long before the first jury assembled. Moral crusaders demanded the ultimate punishment. Studio executives warned performers not to defend Arbuckle in public.

Not everyone stayed silent. Charlie Chaplin, who had worked with Arbuckle at Keystone in nineteen fourteen, told reporters that he could not believe Roscoe was guilty. He said he knew Roscoe to be a genial easy going type who would not harm a fly. Buster Keaton issued a statement in support and was rebuked by his studio. Actor William S Hart, who had never met Arbuckle, publicly presumed guilt. Keaton responded with satire. He purchased a story premise from Arbuckle that parodied Hart as a bully and thief and turned it into The Frozen North in nineteen twenty two. Hart did not forgive the joke for years.

Meanwhile Delmont, whose accusation had set the press alight, quickly became a poor foundation for any prosecution. The defence obtained a letter in which she discussed a plan to extort money from Arbuckle. Telegrams and testimony suggested a pattern of blackmail. Prosecutors quietly dropped her as a witness when it became clear she would not survive cross examination.

First trial

The first trial began on fourteen November nineteen twenty one in the San Francisco city courthouse. The principal witness was Zey Prevon. Public feeling was so raw that shots were fired at Arbuckle’s estranged wife Minta Durfee as she entered the building to support him. The state offered testimony designed to suggest guilt. Model Betty Campbell, who had attended the party, said she saw Arbuckle smiling later that day. Hospital nurse Grace Hultson testified that rape was likely and that bruises matched that story. Criminologist Edward Heinrich claimed fingerprints on a hallway door showed Rappe tried to flee and that Arbuckle stopped her. The hotel doctor, Arthur Beardslee, spoke of an external force harming the bladder.

Under cross examination those threads unspooled. Campbell revealed that the district attorney threatened to charge her with perjury if she refused to accuse Arbuckle. A hotel maid explained that she had thoroughly cleaned the room before investigators dusted for prints. Beardslee admitted that Rappe never told him she had been assaulted. Hultson acknowledged that the bladder rupture might be illness and that the bruises could have been caused by heavy jewellery.

On twenty eight November Arbuckle testified. Reports described him as simple, direct, and unflustered. He said he did not harm Rappe and had helped when she was sick. After more than two weeks of testimony from sixty witnesses including eighteen doctors, the jury deliberated for almost forty four hours. Ten jurors voted not guilty. Two held out. A mistrial was declared.

Second trial

The second trial opened on eleven January nineteen twenty two with the same judge and legal teams. This time witness Zey Prevon testified that the district attorney had pressured her to lie. Another witness, former studio guard Jesse Norgard, claimed Arbuckle once offered him a bribe for a key to Rappe’s dressing room to play a joke. On cross examination Norgard’s credibility collapsed. He was an ex convict under indictment for sexually assaulting a child and was seeking a sentence reduction from the same office prosecuting Arbuckle. Forensic claims also changed. Heinrich disowned his earlier certainty about fingerprints and said the earlier evidence was likely faked. The defence leaned more heavily into Rappe’s history of pain, bladder infections, and heavy drinking.

Confident of acquittal, the defence did not call Arbuckle and did not deliver a closing argument. Some jurors read silence as guilt. After more than forty hours of deliberation, the jury split ten to two in favour of conviction. Another mistrial followed.

Third trial and the written apology

By the time the third trial began on thirteen March nineteen twenty two, Arbuckle’s films had been banned in many places and newspapers had filled their columns for seven months with talk of Hollywood orgies and perversion. Delmont was touring a one woman show about the case. Inside the courtroom, lead counsel Gavin McNab changed tone. He pushed hard, undermining the prosecution witness by witness. A key witness who had once claimed that Rappe said Roscoe hurt me was out of the country and unavailable. Arbuckle returned to the stand, repeated his account, and sat down.

The jury retired on twelve April. Six minutes later they returned. Five of those minutes had been used to write a statement.

Acquittal is not enough for Roscoe Arbuckle. We feel that a great injustice has been done him. We feel also that it was only our plain duty to give him this exoneration under the evidence for there was not the slightest proof adduced to connect him in any way with the commission of a crime. He was manly throughout the case and told a straightforward story on the witness stand which we all believed. The happening at the hotel was an unfortunate affair for which Arbuckle so the evidence shows was in no way responsible. We wish him success and hope that the American people will take the judgment of fourteen men and women who have sat listening for thirty one days to evidence that Roscoe Arbuckle is entirely innocent and free from all blame.

It was an extraordinary and unambiguous apology. It did not repair the damage.

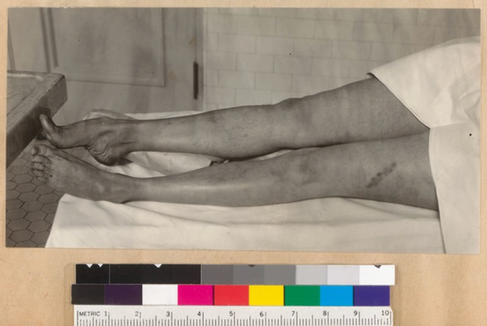

What the doctors found and what the public believed

The autopsy concluded that Virginia Rappe died from peritonitis caused by a ruptured bladder. Doctors found no evidence of sexual assault. Medical testimony described a history of urinary problems and noted that alcohol can aggravate such conditions. Later speculation about a recent abortion could not be verified because the necessary examinations were impossible. Medicine offered possibilities rather than a single clean narrative.

Virginia Rappe in the mourge

The newspapers preferred certainty. Arbuckle was a large man. Rappe was a young woman. A Prohibition era party sounded sinful enough to sell. A suggestion became a headline. A headline became a presumed truth. The bottle story gathered momentum even as witnesses insisted that ice had been rubbed on Rappe’s abdomen to ease pain. William Randolph Hearst’s line about selling more papers than the Lusitania tragedy tells its own story about incentives.

The Hays ban and the price of scandal

Six days after the acquittal, Will H Hays, the head of the industry’s new self regulation body, announced a lifetime ban on Arbuckle. Exhibitors withdrew his films. Paramount pulled Crazy to Marry and shelved two completed features. By December the formal ban was rescinded under public pressure, but the practical effect endured. Most exhibitors refused to book him. Arbuckle’s legal fees totalled more than seven hundred thousand dollars. He sold his house and his cars to pay debts. Buster Keaton quietly signed an agreement to give Arbuckle a share of profits from his own production company, a substantial act of friendship.

William Goodrich and working in the shadows

Arbuckle kept working, mostly out of sight. He directed a string of comedy shorts for Educational Pictures under the name William Goodrich, echoing his father’s names William Goodrich Arbuckle. Keaton, a compulsive pun maker, later joked that the pseudonym read as Will Be Good. Actress Louise Brooks wrote that he was kind on set but that the scandal had left him sweetly dead, a telling phrase for a man whose business had always been life and laughter. Arbuckle directed the Eddie Cantor feature Special Delivery and worked on Marion Davies vehicles. He even lent his name to a café near the MGM lot for a time. His private life however, was unsettled. He and Minta Durfee divorced, he married Doris Deane and later married Addie McPhail.

A final return to the screen

In nineteen thirty two, Warner Bros brought him back to the screen under his own name. He made six two reel Vitaphone talkies at the Brooklyn studio. For the first time audiences heard his voice, a pleasant second tenor. The shorts did well in the United States. When Warner Bros sought to show the first one in Britain, censors refused a certificate and cited the decade old scandal. Even so there was a sense that a small corner of the cloud had lifted.

On twenty eight June nineteen thirty three Arbuckle finished filming the sixth short, In the Dough. The next day he signed a contract to star in a feature. That night he celebrated his first wedding anniversary with Addie. He reportedly said This is the best day of my life. He died in his sleep hours later of a heart attack at the age of forty six.

Why the story lingers

The Arbuckle scandal endures because it sits at the meeting point of several powerful forces. It shows how swiftly a reputation can burn and how slowly it can be rebuilt. It captures the birth of a modern scandal, where outrage and entertainment fuse to sell papers and shape public morality. It charts the rise of studio self regulation, as Will H Hays used the case to justify bans and codes. It also offers a study in uncertainty. A young woman died in agony. No evidence connected a crime to the man accused. Three trials resulted in an apology rather than a sentence. The public did not forgive.

A fair reading remembers what the scandal did to others. Minta Durfee, who supported Arbuckle in court despite threats. Buster Keaton, who gave money and solidarity when it mattered and never believed the worst. Charlie Chaplin, who risked criticism by vouching for a friend’s character. And Virginia Rappe, whose life as a model, designer, and actress has been overshadowed by the manner of her death. The story is not only about one star’s fall. It is also about the character of a new mass culture that had learned how to turn gossip into a business model and learned how to punish anyone who stood in its way.

Sources

Smithsonian Magazine overview of the Arbuckle case

PBS American Experience on the Arbuckle trials and aftermath

https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/biography-fatty-arbuckle

The Independent background on Virginia Rappe and the Arbuckle scandal

Greg Merritt Room 1219 publisher page and research references

https://www.chicagoreviewpress.com/room-1219-products-9781613747925.php

Los Angeles Public Library photo collection entries on the case

Library of Congress silent film resources on Arbuckle and Rappe

https://www.loc.gov/collections/silent-film-and-early-color-moving-images

Contemporary press coverage and Hearst press archives

Hollywood Forever Cemetery page for Virginia Rappe

Find a Grave entry for Virginia Rappe

Paramount and Vitaphone catalogue notes on Arbuckle films

Comments