The Ghost Island of Japan: Inside the Ruins of Hashima (Gunkanjima)

- Daniel Holland

- Jul 4, 2025

- 7 min read

Updated: Jul 16, 2025

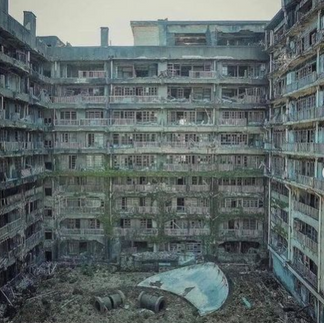

On a misty morning off the coast of Nagasaki, a concrete island rises suddenly from the sea like a warship adrift in time. Locals call it Gunkanjima — Battleship Island — and from a distance, it’s easy to see why. But venture closer, and it becomes something else entirely: a haunting shell of Japan’s rapid industrial rise, a place once crammed with thousands of residents, now utterly silent save for the wind through broken windows. Welcome to Hashima Island — one of the strangest and most fascinating abandoned places on Earth.

A Rock with a Purpose: The Birth of Hashima

Hashima Island is barely 480 metres long and 150 metres wide — a rocky blip in the East China Sea. It wasn’t always cloaked in concrete. In fact, before Mitsubishi got involved in 1890, it was little more than a lump of seabed with a few fishing boats bobbing nearby.

That changed dramatically with the discovery of undersea coal. Mitsubishi bought the island and began mining operations almost immediately. The company didn’t just build tunnels — it built a town. Over the next few decades, Hashima was expanded with sea walls, reinforced concrete, and multiple layers of habitation stacked like Lego blocks over the rock. What emerged was a floating industrial city, one of the most densely populated places in the world.

Life in Tight Quarters: What Was It Like?

At its peak in 1959, Hashima housed over 5,000 people on just 6.3 hectares. That’s more than nine times the population density of Tokyo today.

Families lived in concrete apartment blocks, some of the first high-rise buildings in Japan. These weren’t luxury condos — they were cramped, windowless at times, and designed for function over comfort. Still, there was community: children played on the rooftops, cinemas screened samurai films, there was a hospital, school, public bathhouses, even a pachinko parlour.

The island’s economy revolved entirely around the coal mine. Men descended daily into shafts as deep as 1,000 metres, navigating claustrophobic tunnels and enduring sweltering heat. It was dangerous work, and accidents were not uncommon. Yet it was also a symbol of modern progress. The coal from Hashima fuelled Japan’s industries and helped power its post-war recovery.

A Darker Legacy

While many residents remember Hashima fondly, especially those born there during the boom years, the island also has a more troubling past. During World War II, it became the site of forced labour. Hundreds of Korean and Chinese labourers were brought to the island against their will and made to work in the mines under brutal conditions. Many died underground. This legacy has been the subject of historical debate and tension, especially since Hashima’s 2015 designation as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Japan agreed to acknowledge the use of forced labour as part of the designation, but some critics argue that the acknowledgement has been insufficient or too vague.

The Sudden End: From Bustling Island to Ghost Town

The post-war years were good to Hashima, but coal eventually fell out of favour as oil became king. In 1974, with reserves running low and Mitsubishi pulling the plug on mining operations, the island was evacuated in a matter of weeks.

Residents left everything behind — toys, records, furniture. Doors were locked, but in many cases, windows were left open. What was once a thriving community was now an empty husk. The buildings, already weather-worn, began to crumble under the weight of typhoons and time.

What’s There Now: A Decaying Monument

Today, Hashima remains uninhabited — a forbidden city marooned at sea. For decades, it was completely off-limits. But in 2009, parts of the island were opened for tourism, and now you can catch a boat from Nagasaki and step ashore — albeit only in designated safe areas.

Visitors walk along reinforced paths and viewing decks, peering into the ruins of apartment blocks and collapsing stairwells. There’s an eerie stillness that hangs over everything. Nature is slowly taking back the concrete: vines creep up walls, birds nest in what were once living rooms, and rust blooms across railings like mould.

The island gained global attention in 2012 when it featured as a villain’s lair in the James Bond film Skyfall. Although much of that was filmed in studio, the real Gunkanjima offered the perfect visual shorthand for desolation and decay.

Shadows Beneath the Surface: The Forced Labour Legacy

While many former residents recall life on Hashima with a degree of nostalgia — the rooftop playgrounds, community events, and the uniquely close-knit nature of island living — not everyone’s experience was so positive. The island’s darker past emerged most starkly during World War II, when it became a site of forced labour under Imperial Japan’s wartime policies.

Between the early 1940s and Japan’s surrender in 1945, it’s estimated that around 800 Korean and Chinese men were conscripted and brought to Hashima Island against their will. These labourers, under Japanese colonial rule, were used to fill workforce shortages as local men were drafted into the military. Conditions in the mines were harsh even in peacetime — stifling heat, long shifts, and the constant threat of injury or collapse. For those forced into this work, conditions were often far worse. They endured gruelling labour for little or no pay, under strict surveillance, and with limited freedom of movement.

Many died underground from exhaustion, malnutrition, or accidents, and those who survived rarely spoke of it openly in the post-war years. The scars left behind were psychological as well as physical — not just for the labourers themselves, but also for their families and descendants, many of whom still campaign for formal recognition and apology.

This legacy resurfaced prominently in 2015, when Hashima Island was included in a cluster of industrial heritage sites nominated by Japan for UNESCO World Heritage status. The proposal focused on Japan’s rapid industrialisation during the Meiji era — casting places like Hashima as symbols of technological progress and modernisation. But controversy followed.

Both South Korea and China objected strongly, pointing out that the island’s history included not only innovation but also exploitation. In the end, Japan was granted the UNESCO listing, but under the condition that it acknowledged that “a large number of Koreans and others” had been “brought against their will and forced to work under harsh conditions.”

Japan agreed — and established an information centre in Tokyo to provide details about the forced labour experience. However, critics argue that the resulting exhibits gloss over the worst elements or offer only vague references. In some versions of promotional material, the wartime chapter is barely mentioned at all. Visitors to the island itself won’t find much public signage about it either. In this way, Hashima has become something of a contested space — where history, memory, and politics collide.

The post-war years were good to Hashima. Coal demand surged as Japan rebuilt itself into an economic powerhouse, and the island thrived as a self-contained hub of productivity. Children grew up entirely within its walls, and families carved out routines in what was, despite the concrete, a remarkably vibrant place to live. But progress elsewhere signalled the beginning of the end. By the 1960s, coal was steadily losing out to oil as Japan’s primary energy source. Mines across the country began shutting down, and Hashima — remote, expensive to maintain, and nearing exhaustion of its reserves — was no exception.

In early 1974, Mitsubishi officially announced the closure of mining operations. The decision came swiftly, and with little fanfare. Within just a few weeks, the island’s entire population — over 2,000 people by that time — was relocated to the mainland. For many, it was a rushed and emotional departure.

Residents left behind more than just buildings. Toys, family photographs, vinyl records, newspapers, and neatly folded futons were abandoned as families packed up and boarded ferries for the last time. Doors were locked, but in many cases, windows were left open. Curtains fluttered for years in the salty breeze like fading reminders of daily life that had once filled the narrow corridors and stairwells.

Without people, the buildings — never designed to last for decades without upkeep — began to suffer quickly. Typhoons battered the sea walls, and rainwater seeped into every crack. Concrete started to flake, roofs collapsed, and nature slowly crept back in. What had once been a marvel of compact urban living was now a hollow, crumbling relic — a concrete shell suspended somewhere between memory and oblivion.

What’s There Now: A Decaying Monument

Today, Hashima remains uninhabited — a forbidden city marooned at sea. For decades, it was completely off-limits. But in 2009, parts of the island were opened for tourism, and now you can catch a boat from Nagasaki and step ashore — albeit only in designated safe areas.

Visitors walk along reinforced paths and viewing decks, peering into the ruins of apartment blocks and collapsing stairwells. There’s an eerie stillness that hangs over everything. Nature is slowly taking back the concrete: vines creep up walls, birds nest in what were once living rooms, and rust blooms across railings like mould.

The island gained global attention in 2012 when it featured as a villain’s lair in the James Bond film Skyfall. Although much of that was filmed in studio, the real Gunkanjima offered the perfect visual shorthand for desolation and decay.

Why People Still Talk About It

Hashima isn’t just another abandoned spot with a spooky vibe. It’s a relic of Japan’s industrial surge, a microcosm of urban living at its most extreme, and a monument to the human stories — good and bad — that played out on its narrow walkways.

In many ways, Hashima is a contradiction: it symbolises progress and exploitation, modernity and obsolescence, resilience and ruin. It’s both a historical time capsule and a sobering reminder that even the most ambitious dreams of concrete and coal are no match for the shifting tides of history.

If you ever find yourself in Nagasaki with a few hours to spare, take the ferry out to Gunkanjima. You won’t hear the laughter of children or the roar of mining drills, but you will hear the whisper of history echoing through empty stairwells and shattered halls. And that, oddly enough, makes it all the more unforgettable.