The Beast of Jersey: Edward Paisnel and the Masked Terror Who Haunted an Island

- Oct 28, 2025

- 9 min read

There’s a peculiar stillness to the island of Jersey after dark. Even now, with its polished marinas and quiet lanes, the air holds a kind of weight — a memory that never quite fades. Between 1957 and 1971, the island’s calm was shattered by a string of horrific attacks that left residents terrified to sleep with their windows open.

The man behind them became known as The Beast of Jersey, a figure who haunted both the island’s nightmares and its headlines for more than a decade. His real name was Edward Paisnel, a local builder, husband, and father who hid a monstrous double life behind a mask that looked like melted skin.

But for years before his arrest, the people of Jersey lived in fear, and worse, turned their suspicion upon one of their own. This is the story of how one small island was torn apart by fear, betrayal, and one man’s unfathomable cruelty.

An Island that Slept with the Lights On

In the 1950s, Jersey felt like the picture of safety. It was a place where farmers left their tractors by the roadside, children cycled through parishes without helmets or fear, and the loudest noise after dark was the sea. Many islanders still bore memories of German occupation during the Second World War, years of scarcity, hunger, and control, but those memories were fading into routine island life again.

That changed on a November night in 1957.

A twenty-nine-year-old nurse stood waiting for a bus in the Mont à l’Abbé area when a man appeared out of the dark. He wore something over his face, and spoke softly, with what she described as an “Irish” accent. Before she could move, he looped a rope around her neck and dragged her into a nearby field.

When she was found, she was bleeding badly and needed more than a dozen stitches. Her attacker had vanished.

It was brutal, shocking, but still, police thought, an isolated crime.

But in March 1958, a twenty-year-old woman was walking home from a bus stop in the parish of Trinity when she, too, was dragged into a field and raped. That July, a thirty-one-year-old woman was attacked in almost identical fashion. In August 1959, a young girl walking home in Grouville was seized, bound, and assaulted.

By the autumn of that year, Jersey police had a problem they couldn’t explain, a predator who struck seemingly at random, in parishes miles apart, and vanished again into the hedgerows.

The Beast Emerges

When detectives compared the cases, they began to notice patterns. The man was described as about five feet six, middle-aged, with a stocky build and a soft Irish accent. He often wore gloves and a raincoat that smelled strongly, “musty,” said every victim.

He struck only on bright, moonlit nights, the kind islanders called “fine nights for a walk.” And always on weekends, between ten at night and three in the morning.

Each woman or girl had been seized by the neck with a rope or cord, then dragged into a field. Some described his voice as calm, even conversational. He seemed to enjoy talking. He mentioned a wife, a dead mother, and sometimes claimed to have killed before.

As the attacks grew, so did the fear. By 1960, Jersey’s quiet roads emptied early. Fathers met the last bus with lanterns. Children were no longer allowed to walk alone.

And the Beast, whoever he was, seemed to be watching.

The Children

In the early hours of Valentine’s Day 1960, twelve-year-old Peter (a pseudonym, as he was a minor) woke in his bed in Grands Vaux to see a torch beam shining across his face. The man ordered him out of bed, tied a rope around his neck, and led him silently out into the night.

He was taken to a nearby field, assaulted, and returned home before dawn. The boy’s trembling voice described the same things police already knew, the musty smell, the rope, the Irish accent.

A month later, a twenty-five-year-old woman waiting at a bus stop was offered a lift by a man in a Rover car. He said he was a doctor collecting his wife. She never saw his face clearly, but she noticed the cap, the gloves, and the air of false gentleness. He drove her into a field, beat her, tied her hands behind her head, and raped her. When she tried to escape, he told her calmly, “I’ve killed before.” She fled barefoot across the field.

Then, in March, came an attack that shook Jersey to its core.

In an isolated cottage in St Martin, a forty-three-year-old mother woke at half past midnight to a telephone ringing downstairs. When she answered, there was only a click. Later, she heard a noise.

As she reached the bottom of the stairs, the lights went out. The phone line had been torn out.

A man grabbed her in the dark and demanded money. He threatened to kill her. When her fourteen-year-old daughter came down the stairs, he let the mother go. She ran to a nearby farmhouse for help. When she returned, she found her daughter in her bedroom, assaulted and bound.

The pattern had escalated. The Beast was now entering homes.

Panic on the Island

By 1961, the Beast had assaulted three more children, a twelve-year-old boy in Mont Cochon, an eleven-year-old in St Saviour, and an eleven-year-old girl in St Martin.

The island’s police were overwhelmed. Jersey was only forty-six square miles across. Where could such a man hide?

Scotland Yard sent Detective Superintendent Jack Mannings to help. He told islanders bluntly,

“Someone on this island knows this man. You all must turn detective.”

He described the attacker as about forty-five, of medium build, with a moustache, gloves, and a raincoat. He struck on moonlit nights, between ten and three. He used rope, tied hands, and blindfolded victims. He spoke softly. He carried a torch.

For a while, the publicity worked. There were no attacks for nearly two years.

But then came one of Jersey’s darkest chapters.

The Witch Hunt: The Case of Alphonse Le Gastelois

In 1960, during the peak of the panic, police grew desperate. One name rose through rumours: Alphonse Le Gastelois, a forty-two-year-old fisherman and farmer from St Martin.

Le Gastelois lived a solitary life. He was eccentric, known for his long walks, his odd clothes, and his sharp tongue. He had been accused once of “being seen near” a girl — though no charges were ever brought. That was enough for the frightened public.

When another child was attacked, suspicion turned violent. Newspapers printed his photo. People whispered that the police “had their man.”

A vigilante mob burned down his house. His goats and chickens were killed. Le Gastelois fled to the tiny, uninhabited Écréhous islets off Jersey’s coast, living there in exile for fourteen years.

Only later did it become clear that he had been innocent all along, when the Beast’s attacks continued after he was driven away. The real killer had simply watched, unseen, while an innocent man was persecuted.

The Letter

In 1966, after another lull, a letter arrived at Jersey Police Headquarters. The handwriting was uneven and littered with mistakes. The tone was mocking.

“I think that it is just the time to tell you that you are just wasting your time… I have always wanted to do the perfect crime… Let the moon shine very bright in September because this time it must be perfect. Not one but two. I am not a maniac by a long shot but I like to play with you people.”

In August that year, as promised, a fifteen-year-old girl in Trinity was attacked. She was raped and left with strange, evenly spaced scratches on her torso, as though clawed by a machine.

Then, for four years, silence.

1970: The Return

On a warm August night in 1970, a thirteen-year-old boy in Vallee des Vaux woke to see a light in his face. The man who stood over him had black spiky hair and wore a grotesque mask. He tied a rope around the boy’s neck and led him outside, where he was assaulted.

He warned the boy to stay silent or “someone will hurt your mother and father.”When police examined the boy, they saw the same long, parallel scratches found on the girl four years earlier.

Jersey held its breath. The Beast was back.

Police interviewed nearly thirty thousand people on the island, but no leads emerged.The fear became something unspoken — not discussed in cafés or churches, but heavy in every home.

What finally ended it was not forensics, nor luck, but a simple traffic stop.

The Night the Beast Was Caught

On 10 July 1971, just before midnight, police officers John Riseborough and Tom McGinn were patrolling St Helier when a Morris 1100 sped through a red light. They gave chase. The car swerved, clipped other vehicles, and careered through a hedge into a tomato field. The driver fled. Riseborough tackled him in the dark.

At the station, they began to notice details that chilled them.

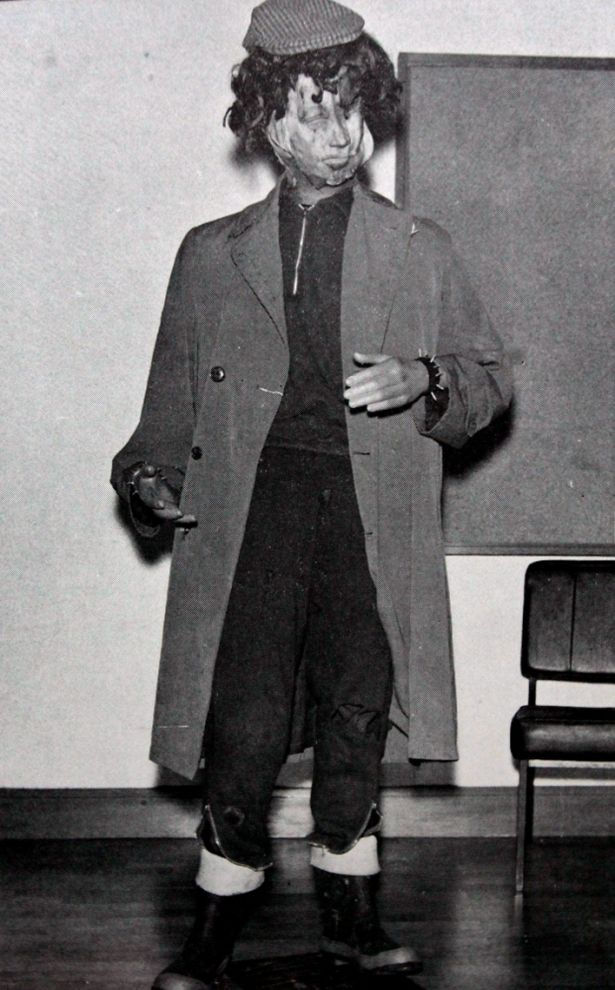

The man’s raincoat reeked of mildew. One-inch nails jutted from the shoulders and lapels. More nails lined the cloth wristbands he wore beneath his sleeves. In his pockets were cords, adhesive tape, a torch with a slit of light covered by black tape, and a spiky black wig.

Then came the mask, home-made, terrifying, like the face of something burned and inhuman.

His name was Edward John Louis Paisnel, a forty-six-year-old building contractor from St Martin.

He was married to Joan Paisnel, who ran a foster home called La Preference with her mother. The children there knew him as “Uncle Ted.” Every Christmas he dressed as Santa Claus and handed out gifts.

His only known brush with the law had been in the 1940s, when he was jailed for stealing food during the German occupation, to feed hungry families.

Now, the kindly handyman stood revealed as one of Britain’s most depraved predators.

When asked what he was doing that night, he calmly replied that he was “on his way to an orgy.” The nails, he said, were “for protection against martial arts.”

Police searched his home. In a locked room, they found a blue tracksuit, wigs, false eyebrows, photographs of houses and bedrooms, books on black magic, and a crude altar. On one wall hung a curved wooden sword. The room smelled unmistakably — musty.

The Beast of Jersey had been caught.

The Trial

Paisnel was charged with thirteen counts of rape, indecent assault, and sodomy against six victims — five of them children.

In court, prosecutors painted a picture of a man obsessed with planning. He would photograph homes, learn the layout, and return months later to attack sleeping children. He wore the mask not just to hide but to terrify. The torch slit blinded his victims but left him able to see.

He enjoyed the game, the taunting, the letter, the fear.

He told police he was a student of the occult and a descendant of Gilles de Rais, the fifteenth-century French nobleman executed for child murders. His wife confirmed that the 1966 taunting letter was in his handwriting.

The jury took just thirty-eight minutes to find him guilty on all counts.The judge called him “a cunning man, but not a mad one.”He was sentenced to thirty years in prison.

Paisnel appealed and lost. He served twenty years as a “model prisoner.” When released in 1991, he returned briefly to Jersey but was driven off by angry crowds. He settled on the Isle of Wight, where he died of a heart attack in 1994.

Shadows That Remain

After his death, new rumours emerged. During the Independent Jersey Care Inquiry into historic abuse at Haut de la Garenne, documents suggested Paisnel had been a visitor there, and that he may have prowled La Preference at night wearing his mask.

One former resident, known only as Mr D, described those nights in haunting terms:

“One night I was asleep and felt a presence. It was Paisnel, standing there with a mask. That house was eerie. You’d see cats strung up, and once I saw him strangling one. I always knew something evil was going on there.”

Police later stated there was “no firm evidence” linking Paisnel directly to the Haut de la Garenne offences under Operation Rectangle. But survivors who lived through that period often said his shadow still hung over the island’s darker history.

The Victims and the Fear

For the women and children he attacked, the damage lasted a lifetime.Many never spoke of it again. Some emigrated. Others stayed but couldn’t sleep through a windy night. The sounds,a creak on the stairs, the wind against a latch, brought everything back.

For families, the shame and silence of the time made recovery harder. The 1950s and 60s were not decades of open discussion about sexual trauma. Victims were often told not to talk, not to make a scene.

Yet they were the ones who had the courage to describe the mask, the nails, the rope, the smell, and those details helped catch him.

Their bravery ended the nightmare.

Justice and Injustice

The story of Edward Paisnel is not just about one predator. It’s also about fear, hysteria, and what happens when a community turns against itself.While the true Beast roamed free, an innocent man, Alphonse Le Gastelois, lost his home, his reputation, and his peace.The attacks he was blamed for continued even as he lived alone on a barren rock in the sea.

When Paisnel was finally unmasked, the island felt both relief and shame. Relief that the nightmare was over; shame that fear had made them cruel.

Legacy

Today, the mask still exists, held in police archives, a grotesque relic of a man who terrorised a whole island. Jersey has changed since then, but older residents still recall the long years of moonlit fear.

For them, it isn’t just the story of a monster caught. It’s a reminder that evil can wear an ordinary face — and that true courage sometimes belongs to those who refuse to stay silent.

Sources

The Beast of Jersey: The True Story of Edward Paisnel, Jersey’s Notorious Masked Attacker – Historic UK https://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofBritain/The-Beast-of-Jersey/

Independent Jersey Care Inquiry: Final Report (2017) – States of Jersey https://www.gov.je/SiteCollectionDocuments/Government%20and%20administration/R%20Independent%20Jersey%20Care%20Inquiry%20-%20Final%20Report%202017.pdf

Operation Rectangle: Historic Child Abuse Investigation, Jersey Police Reports (2008–2010) – States of Jersey Police https://jersey.police.uk/news-appeals/2010/operation-rectangle-historic-abuse-investigation-summary/

Press Coverage of the Trial of Edward Paisnel, Jersey Evening Post Archives (1971–1972) – Jersey Evening Post Digital Archive https://www.jerseyeveningpost.com/

Comments