From Rags to Riches: The Story of Sarah Rector Americas Youngest Oil Millionaire

- Daniel Holland

- Oct 23, 2025

- 11 min read

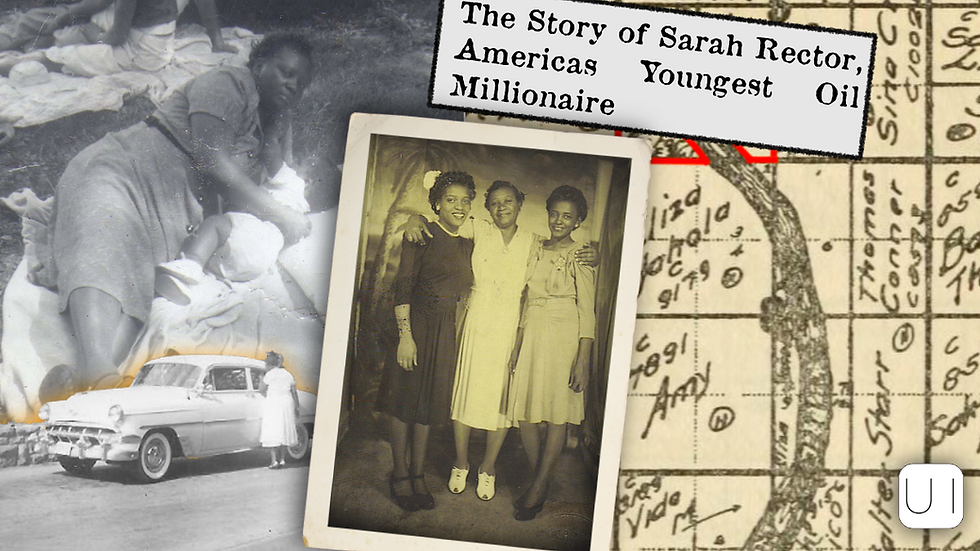

If you search for Sarah Rector today, you will meet a ghost made of headlines and miscaptioned photographs. One shows a solemn girl in plaid holding a chair. Another shows a woman with plaited hair and a lace collar. Her nieces say neither image is their aunt. The truth is quieter, closer, and much more compelling. It begins in a two room cabin near Taft in Indian Territory and rises on a gust of crude that changed a family’s life, then gets muddled by rumours, lawsuits, scary nights, and the long memory of a community that knew both joy and danger.

As one niece remembered, "We called her Aunt Sister because our mother always referred to her as Sister. She had more things than we did but she did not act any different or dress any differently." That tone of ordinary warmth runs straight through the life of a Black girl who, at the age of eleven, was called 'the richest coloured girl in the world.'

A family rooted in Creek Freedmen history

To understand why oil under a rocky patch of land made Sarah rich, you have to understand how she came to hold that land at all. Sarah was born on 3 March 1902 near Taft in Indian Territory, now Oklahoma. Her parents, Joe and Rose Rector, were Black citizens of the Muscogee Creek Nation and descendants of Creek Freedmen. Under the Treaty of 1866, Black people who had been enslaved by Creek citizens and their descendants were recognised as citizens, recorded on the Dawes Rolls, and eligible for 160 acre allotments as the United States pushed communal land toward individual plots.

The family’s ancestral story carries the names and movements of the nineteenth century. Creek communities were forced west in the 1830s. Leaders like Opothleyahola refused to join the Confederacy in the Civil War. Freedmen such as York McGilbra Jackson and Jack Benjamin who later took the name John Rector served in Union forces and returned home to the Territory. By the turn of the twentieth century, Black families built towns like Twine, later renamed Taft, which sat a few miles west of Muskogee. Taft had newspapers, shops, a brickyard, and a soda pop factory. Life was lean but lively and centred around church, dances, and farming cotton and corn.

Joe and Rose raised their children in that world. Rebecca came first in 1901, then Sarah in 1902, then Joe Jr. in 1906. They lived in a two room cabin on Rose’s allotment. The allotments available for the children by 1906 were not the most prized. Sarah’s plot lay about fifty miles to the northwest near a bend of the Cimarron River. It was sandy, rocky, and considered poor farmland. Its valuation was around five hundred dollars. Worse, it carried an annual tax bill near thirty dollars which, in modern terms, approached a thousand pounds. Taxes always seemed to be part of the Rector family story.

Leasing the land nobody wanted

With little chance of coaxing crops from such ground, Joe looked for relief. He first tried to sell the children’s allotments. He managed to sell Rebecca’s for seventeen hundred dollars in 1910, a helpful sum for a growing family but not a complete answer. He then turned to leasing. In February 1911 he signed a lease on Sarah’s land with an oil company. At first nothing came of it. A second lease also passed without luck.

But the oil business in Oklahoma was a fever. Strikes on land owned by children had already made headlines and, tragically, had drawn violence. In Taft itself, in 1912, thirteen year old Harold Sells and his ten year old sister Castella were targeted for their oil wealth. Dynamite was placed under their home at night. Harold died instantly. Castella, trapped under burning timbers, did not survive. Several men, Black and white, were implicated. The lesson was clear. Sudden wealth could make children a target.

The gusher that changed everything

In March 1913, an independent driller named B B Jones began testing Sarah’s parcel near the Cimarron. In late August he hit a gusher. The well flowed an estimated two thousand five hundred barrels per day. Sarah’s royalty was around one eighth, which meant roughly three hundred dollars per day at the time. Contemporary accounts recorded ten and eleven thousand dollars in a single month. Adjusted to today, that was hundreds of thousands per month. The family that had been getting by in a cabin now had income larger than many businesses.

News travelled fast. Headlines shouted Negro Girl Will Pay Largest Tax and Girls 112,000 a Year. Letters arrived from strangers seeking loans, gifts, and marriage. Some press reports got basic facts wrong and shaded others to fit familiar tropes about helpless Black families and cunning white guardians. In November 1913, The Chicago Defender ran a story that claimed the child was forced to live in a shack and was denied proper schooling and comfort. It said she slept on the floor. That version of events set off a chain of interventions.

Guardianship and the judge who pushed back

Oklahoma courts at the time commonly appointed white businessmen as guardians for wealthy Native citizens and Freedmen children, supposedly to protect their assets. Some guardians abused that power for profit. Sarah’s father had chosen a neighbour and cattleman, T J Porter, as guardian before the big strike. After the Defender article, national Black leaders took notice. W E B Du Bois wrote to the local judge in Muskogee County to ask about Sarah’s welfare and education. Booker T Washington made enquiries and later welcomed Sarah and her sister to the Tuskegee Institute’s preparatory school.

Judge J H Leahy replied to Du Bois in June 1914, a letter the Rector family later preserved. He wrote that he had jurisdiction over Sarah’s estate and had met with the family, the guardian, and the lawyers soon after oil was found. He said he insisted on improvements for the child’s benefit. A five bedroom house was authorised for the family. He noted Sarah was already in school at Taft and that her father had agreed she would soon attend a more prestigious school. He also pointed out that the parents had chosen Porter and that most of Sarah’s earnings were placed in investments rather than allowed to pass through sticky fingers.

The image of a neglected child sleeping on bare boards did not match the records. Nor did the claim that a guardian was simply pocketing her fortune. That is not to say the period was easy. It was exacting. It was public. And it was dangerous. As one Oklahoma City playwright, Kathleen Watkins, later said about learning of Sarah’s story, It got my heart because I can only imagine being that age and being told I have all of this money and not really understanding any of it. When people began to come from all over to see this little Black girl, it must have been scary for her.

Schooling away from home and the move to Kansas City

In autumn 1914, Sarah and her older sister Rebecca left Oklahoma for the Children’s Home School at Tuskegee in Alabama. From there they went on to study at Fisk in Tennessee. Around this time the family made a quiet, strategic shift north to Kansas City, Missouri. By 1917 and 1918 they were living at 1218 Euclid. Soon after, Rose Rector acquired a handsome brick house at 2000 East 12th Street. Locals now call it the Rector Mansion. It was large and elegant and anchored a neighbourhood that pulsed with Black enterprise and music. The landmark district at 18th and Vine would soon be a cradle of jazz.

A newspaper caption later called it the Sarah Rector Mansion, but the title deeds tell a different story. The house was purchased by Rose, the mother, and it was home to the entire close knit Rector family. That detail matters to the nieces. The house belonged to us all, they say, and the matriarch signed the papers.

By 1918, there were reports of fifty wells on Sarah’s leases. Contracts were signed. A major arrangement with a Kansas firm carried a huge bonus. Porter had also diversified Sarah’s wealth into land and business holdings, including a two storey property in Muskogee with the Busy Bee Cafe below and the Busy Bee Hotel above. By eighteen, Sarah was a millionaire on paper and in real assets.

Parties, cars, and the normal life behind the legend

When Sarah reached twenty one in 1923 she took direct control of her finances. Her nieces remember what that looked like from the inside. There was a department store downtown where Black customers could not shop during regular hours. For Sarah, they would lock the doors and let her in after closing. They would send clothes to the house to try on. The giggles in that memory are affectionate rather than flashy. Aunt Sister loved to shop and she loved cars. She and an uncle kept crashing them and buying new ones.

Kansas City in the 1920s was a river of music. The Rectors entertained. Duke Ellington and Count Basie visited. Sarah loved a good party and she adored music. She also liked to do ordinary family things. She bought a farm in Wyandotte County and the whole family worked the garden and goofed with the animals. The geese chased the children. Chickens from the yard became dinner. If the nieces turned green when the headless birds ran, that is the sort of memory that lodges in your bones and becomes a family classic.

Marriage, loss, and a reality check

Sarah married Kenneth Campbell, a young businessman with a car dealership near 18th and Vine. They had three sons, Kenneth, Leonard, and Clarence. The 1929 market crash, like a strong wind, rattled the family’s fortune. Bonds plunged. Royalties thinned. Taxes came due. The big 12th Street house changed hands and became a mortuary. Sarah and Kenneth divorced around 1930. In 1934 she married William Crawford, who owned a well known restaurant called Dicks Down Home Cook Shop. They remained together until Sarah’s death in 1967.

Not every twist in the family story goes down easy. In 1922 Joe Rector, Sarah’s father, became entangled with a notorious con man named Jim Manuel who dangled a fantastical oil claim in Mexico. Joe travelled south, money evaporated, and Manus vanished. Joe fell ill on the journey home and died in Dallas. Accounts differ on the fine points, as family oral history often does, but the shock was felt all the same. Rose handled the arrangements and brought him back to Taft for burial at Blackjack Cemetery, the family plot. The nieces remember what their grandmother’s grief looked like and how her steady hands kept the family together.

The photographs that are not her

If you type Sarah Rector into a search box today you are likely to see two black and white portraits. Her nieces insist those are not Sarah. One image appears to be of Callie House, a prominent reparations activist born in the 1860s. The other is an unknown young girl. The family is understandably frustrated. If our family is going to be out there, at least have the right picture out there, they say. It is one more sign of how a life can get swallowed by legend, then repackaged by an internet page that needs a face to stick by a name.

Honorary white and other oddities of the time

As Sarah’s wealth became front page news, the Oklahoma Legislature reportedly entertained the idea of declaring her an honorary white, a legal absurdity that speaks volumes about the colour line of the era. The reasoning sprang from access to public accommodations such as first class train travel. You read that correctly. Instead of taking on the racism of the rules, some officials tried to pretend the richest Black child in the state could be treated as white when it suited them.

There were also serious Black led interventions to protect children whose estates were being siphoned. The Chicago Defender’s alarm prompted Du Bois to push the NAACP to look hard at guardianship abuses. The organisation created a Children’s Department to monitor cases. Booker T Washington personally made sure Sarah was placed at Tuskegee. These efforts did not erase systemic problems overnight, but they mattered. They created records. They swayed judges. They gave families leverage.

Wealth, work, and the long after

Sarah did not disappear when the gushers slowed. She never stopped being family minded. She invested in real estate. She kept the Wyandotte farm as a retreat. She hosted, laughed, and danced. She was ticketed more than once for fast driving and reportedly grinned at the officer while asking, Dont you know who I am. That is a line every niece will repeat with a smile because it carries a little mischief and a lot of pride.

Money ebbed with the Depression, but she remained secure. Her mother, Rose, died in 1957. Sarah died on 22 July 1967 of a cerebral haemorrhage. She was sixty five. In a circular moment that feels like a novel, her body was prepared at the mortuary that now occupied the old family home on 12th Street. She was brought back to Taft and laid to rest in Blackjack Cemetery, where so many of the Freedmen families who built that community are buried.

What the nieces want you to know

Sarah’s nieces, Donna Brown Thompkins, Rosina Graves, and Debbie Brown, learned the full measure of their aunt’s story only after she died. They already knew she had a little more than most people and that she liked cars and music. They did not know just how large the oil checks had been or how many strangers wrote letters to an eleven year old girl. They did not know that while newspapers half a world away claimed she slept on the floor, her home would one day welcome musicians like Duke Ellington and Count Basie, their laughter echoing off the parlour walls

They also remember fear. "After she passed, our mum and our uncle went to Oklahoma a lot. They told us not to go down there talking about being a Rector. It was dangerous, not worth it." The story of the murdered Sells children was never far away. That caution kept the nieces from exploring the Oklahoma side of their aunt’s life for years. They needed to keep their heads down. That is as honest as it gets.

And they want errors corrected. They want people to know the house was bought by Mama Rose. That guardianship was chosen by the parents and carefully overseen by a judge who took an interest in preventing abuse. That Sarah was in school and then sent to the best schools in the Black South at the time. That the photographs you see online are not her. That five generations of Rectors have stayed in Kansas City and still drive past the boarded up mansion, thinking about what it meant to their family and what it could be again.

Why her story matters now

Sarah’s life is a window into the tangle of law, race, land, and money in early twentieth century Oklahoma and Missouri. It shows the reach of allotment policy into Black communities within the Five Tribes. It shows how Black towns built institutions and businesses that thrived despite segregation. It shows how wealth could buy a Cadillac and a piano and still could not buy safety or dignity for a child without community vigilance.

It also shows how misinformation travels. A single headline in 1913 and a few mislabelled images in the present have shaped public understanding more than letters from a judge or the testimony of living family. By spending time with the people who knew Aunt Sister, and by weighing the paper record against rumour, we can hold a fuller, kinder picture.

Sarah Rector did not ask to be rich. Oil breached through a rocky field and landed a fortune in her lap. With help, her family kept her safe, educated her, moved to a city where she could be a teenager and built a life that was at once grand and ordinary. She was a party thrower, a fast driver, a loyal sister, a mother, and a quiet farmer on weekends. When the music fades and the headlines curl, that is the portrait that remains.

Sources

Sarah Rector’s Fortune – Oklahoma Living Magazine https://www.okl.coop/story/sarah-rectors-fortune/

Sarah Rector – The Pendergast Years (Kansas City Public Library) https://pendergastkc.org/articles/sarah-rector

Sarah Rector’s Nieces Separate Fact from Fiction – 41 Action News / KSHB Kansas City https://www.kshb.com/news/kc-chronicles/chronicles-of-kc-sarah-rectors-nieces-separate-fact-from-fiction

Rector Mansion – African American Heritage Trail of Kansas City https://aahtkc.org/rectormansion

Sarah Rector 11-Year-Old Who Became the Richest Black Girl in America in 1913 – Black Enterprise https://www.blackenterprise.com/sarah-rector-11-year-old-richest-black-girl/

Searching for Sarah and Finding History – First Opinions, Second Reactions (Purdue University Press) https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1424&context=fosr

An 11-Year-Old Was Given an Allotment of ‘Undesirable’ Land Beneath Which Was Millions in Oil – Business Insider https://www.businessinsider.com/sarah-rector-richest-black-girl-in-america-history-oil-rights-2024-1

Sarah Rector Entrepreneur Born – African American Registry https://aaregistry.org/story/sarah-rector-entrepreneur-born/

Rector, Sarah (1902–1967) – The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History & Culture https://okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry?entry=RE014

The Black Oil Millionaires of 1920s Oklahoma – NPR https://www.npr.org/2020/02/27/809756703/the-black-oil-millionaires-of-1920s-oklahoma

Sarah Rector Was the Richest Black Girl in America in 1913 – NBC Newshttps://www.nbcnews.com/news/nbcblk/sarah-rector-was-richest-black-girl-america-1913-n1256214

Sarah Rector – National Women’s History Museum https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/sarah-rector

Sarah Rector Exhibit – Kansas City Museum https://www.kansascitymuseum.org/sarah-rector/

Rector, Sarah (1902–1967) – Oklahoma Historical Society (duplicate entry for archival completeness) https://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry?entry=RE014

Comments