Malcolm Campbell’s Leap to Three Hundred: How Blue Bird, Rolls Royce and an Obsession Turned Salt and Sand into Speed

- Daniel Holland

- Nov 3, 2025

- 12 min read

If you have ever stared at an old black and white photograph of a long blue needle on vast shining sand and wondered how on earth a human being kept that thing in a straight line, you are in the right place. This is the story of Sir Malcolm Campbell’s final climb from the rough surf and razor shells of Daytona to the bright white crust of Bonneville, and how an already famous record breaker re-engineered his way through failure, discomfort, national pressure, and sheer terror to be the first person to drive a car beyond three hundred miles per hour.

“Worst ride of my life,” Campbell said more than once of his bucking runs on the beach. Later, after the white salt and the quiet figures with stopwatches, the smile came back. “I said I would retire at three hundred,” he told reporters. He meant it.

From Sunbeam to Blue Bird: a man and his number

By the middle of the nineteen-twenties, Malcolm Campbell was already a regular in the newspapers. He set absolute world land speed records again and again, six times by 1931, each time bringing the Blue Bird name back to the front page. He did it with a progression of machines that read like a mechanical family tree. First a Sunbeam 350 HP. Then a Napier-powered special at Brooklands. Then the Campbell-Napier-Railton Blue Bird, a long, blunt instrument with a Napier Lion W-12 that sounded like a dozen kettledrums when it wound up on the sand.

Each iteration grew faster and a little more sophisticated. The line from Sunbeam to Napier to Railton was not just about power. It was about where to put weight, how to get rid of heat, how to keep a driver sitting inches from a spinning prop shaft from being beaten senseless by a surface that looked smooth until the tyres found every hollow. Campbell did not work in isolation. He had Reid Railton to think about geometry and structure, the quiet genius of Brooklands. And he had Leo Villa, practical magician, who could make an engine purr at breakfast and roar at lunch.

By February 1932, the Campbell-Napier-Railton Blue Bird had set 253.968 miles per hour over the flying mile on Daytona Beach. Then something changed in Campbell’s mind. He did not just want to be faster. He wanted to cross a psychological border. Three hundred. A perfectly round number that mocked every car of its day. The Lion engine was all courage and noise, but it was out of breath. If the number was to give up its secret, a new heart would be needed.

Enter the Rolls Royce R: a racing heart built for the sky

The solution was both elegant and audacious. The Rolls Royce R aero engine, born for the Schneider Trophy and proven in Supermarine seaplanes, was available if the right arguments were made in the right rooms. Campbell made them. In April 1932 Rolls Royce agreed to loan an R unit, specifically R37.

Here is the core of what arrived. A sixty-degree V-12 with a double-sided supercharger impeller, six inches of bore and six point six inches of stroke, all told thirty-six point seven litres. More than two thousand three hundred horsepower at around three thousand two hundred revolutions per minute, and in sprint trim able to run a little faster and harder again. The figures felt like science fiction next to the W-12 Lion it replaced.

Fitting it was not a simple swap. The R was longer, taller, and heavier. Railton and Villa had to cradle it in a subframe and stiffen the rest of the chassis. The three-speed gearbox was strengthened and re-geared, the rear axle ratio was altered, the left side road springs were stiffened to resist torque, and the cockpit remained offset to the right, which meant the prop shaft ran left of centre like a taut cable.

Cooling was the next enemy. A new radiator sat on a forward frame extension. A sculpted header tank nestled in the void ahead of the engine. The plumbing was large and the capacity huge, about one hundred and thirty-six litres. Most striking was the forward-facing scoop perched above the radiator. It rammed fresh air under the tank into the four carburettors. That scoop was good for roughly two pounds of extra boost. The fuel tank stayed aft in the tail and held about one hundred and five litres.

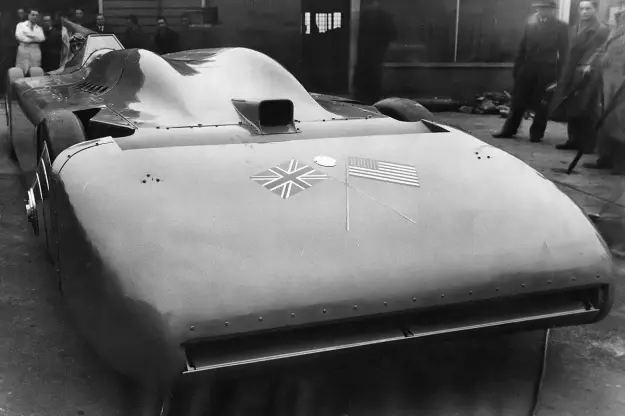

When the aluminium body was reworked, the car looked different. In the wind tunnel at Vickers, Rex Pierson helped choose a shape that made twin humps over the cylinder banks, with the valve covers effectively forming the top of the cowling. The new nose was sleeker, but the humps stole some of Campbell’s view. The cockpit was raised a little to compensate. Exhaust stubs sprouted along the flanks. Photographs of Campbell and his son Donald with the completed car in January 1933 show a machine both purposeful and slightly improvised, which is exactly what it was.

“Campbell Special” was painted on the fin. It was not vanity. It was a reminder to the crew that this one was going to be personal.

Daytona 1933: speed, shells, and pain

When the team reached Florida in early February 1933 they found Daytona Beach in a foul mood. Only nine usable miles. Soft patches. Shell fragments like knives. They waited. They tested. A gearbox overheated and oil had to be re-plumbed. Campbell hurt his left hand during shifting. The whole time the Atlantic wind blew, pushing and smoothing and then tearing little ridges into the sand again.

On 22 February they went for it. The numbers were fierce. Just over two hundred and seventy-three miles per hour over the mile southbound, just over two hundred and seventy on the return northbound, with the five-kilometre figures a little lower. Average for the mile was 272.108 miles per hour. A new record by a handsome margin. And yet not the number. Not the number.

The tyres had been cut by shells and the car had spun its rear wheels so much that Campbell felt it wandering on invisible rails. “Very unsteady,” he said, and he meant the sort of unsteady that lays a shadow across your sleep. He had planned to run again the next day, but his hand ached and the beach was getting worse. He made a decision that only a disciplined racer makes. He packed up and sailed home, already thinking about the next version of the same machine.

The great rebuild: double wheels and a new face

Back at Brooklands the team could not start the rebuild immediately, but by April 1934 the car was on stands at Thomson and Taylor. Campbell bought R37 outright. Attention turned to traction and to drag.

Traction first. The rear axle had suffered and would not be trusted again. Railton designed a new unit with twin rear wheels on each side so that four contact patches would work the salt or sand together. Each rear tyre would run at about one hundred and ten pounds per square inch, the fronts remained at one hundred and twenty-five. The axle used twin pinions engaging separate shafts, reducing tooth load and giving a tiny fore-aft stagger between the left and right, only about thirty-eight millimetres.

Air brakes appeared behind the double rear tyres, vacuum-actuated panels with about two square feet of area each. In an age before parachute braking was normal, these were a sober and clever way to calm a big car after a big number. The fuel tank moved to the left side between the wheels, capacity rising to about one hundred and eighty-two litres, in part to counter engine torque and in part to make the tail slimmer.

Then came the nose and body. A new radiator spanned the whole front and sat behind a narrow slot that the driver could close for a brief spell, knife-like, through the flying mile. The body grew clean flanks and a taller fin rising from the headrest. It was all shaped in the tunnel, then hand-formed by J Gurney Nutting and his craftspeople in aluminium. The effect was dramatic. The new Blue Bird looked less like a fighter and more like a dart.

The car was heavier now, around four thousand seven hundred and forty kilograms with ballast, longer by a little, and wider across the flanks. But the wind would like it. And if the wind liked it, so would the stopwatch.

Daytona 1935: the last fast run on the sand

They reached Daytona at the end of January 1935. The weather sulked. Ab Jenkins, the American endurance man, came to visit and talk about a place in Utah called the Bonneville Salt Flats. He even brought a film to show how smooth and vast it was. Campbell listened politely and then carefully. The seed was planted, but his car was here, and he would run.

Test runs on 2 and 3 March uncovered new discomforts. Body panels near the exhaust warped and leaked fumes into the cockpit. More troubling, power seemed to dip when Campbell pulled the radiator shutter closed. Still, on 7 March it happened. Southbound across the dark diesel line that marked the measured distance, the car clocked 272.727 miles per hour over the mile. Northbound, despite a rougher surface, it found 281.030. The average for the mile was 276.816, with the kilometre a touch lower and the longer distances lower again. Enough for a stack of records, but not for the one that mattered. It would be the last time anyone set the absolute record on that beach.

Campbell later admitted he had been lifted clean out of his seat by the bumps and that his goggles were pushed down so that his eyes were stung by the air. It is an intimate detail and it tells you what these runs were like. A man in shirt sleeves and a helmet, holding a wheel while a twelve-cylinder aeroplane engine tried to pull a long blue car faster than the wind had ever seen a car go.

The shutter problem nagged at the engineers. Back in England they put a second set of instruments in the right side fairing and pointed a small camera at them so the crew could study what boost and temperatures did when the slot was closed. The wind tunnel gave them another clue. When the radiator slot was shut, the airflow dodged the induction scoop and starved the carburettors. The quick fix was a longer scoop that reached past the radiator outlet, gulping clean air. It looked a little odd, which is how you often recognise an honest solution.

Bonneville 1935: a white horizon and a round number

By August the Blue Bird and its people were at Bonneville. Rolls Royce loaned a second engine as a spare. The crew rolled across the flats and built a thirteen-mile course that was straight as a ruler. On 2 September a test run showed that salt could cake between tyres and fairings, so they trimmed the clearances.

On the morning of 3 September Campbell climbed into the cockpit. The wind was quiet. The salt was almost luminous. He set off to the north-east, the V-12 a strange mixture of harsh and smooth on the surface. Over the measured mile the clocks caught him at 304.311 miles per hour, which is to say he covered the mile in a shade under twelve seconds.

Then the drive gave him a small scare. With the radiator slot closed the cockpit filled with fumes and a mist of oil, and as he braked near the end of the run the left front tyre burst, caught fire, and threw sparks. He coaxed the car down and stopped shy of the pits. The crew sprinted with jacks and tools. All six tyres were changed. That smouldering front took the longest and their one-hour window ran thin. At last he went back the other way. The mile south-west measured 298.013 miles per hour. He kept the shutter open this time.

When he climbed out, he was certain he had done it. Three hundred lived in his bones even if the paper tape had not yet been added up. A timekeeper told him the average was 301.1. The crew cheered. Then a mistake. A correction was handed down. The figure was 299.874. The grin faded. Campbell nodded and said he would go again tomorrow. Dinner that night was quiet.

Here is the part I love. The timekeeper came back. An error had been made in the arithmetic. The original number was right after all. 301.129 miles per hour across the two runs. The round number belonged to Campbell now, and the flats where Ab Jenkins had spent years proving the surface belonged to the land speed record. The final absolute numbers on that day included 301.473 over the kilometre and 292.142 over five kilometres. The car itself bore scars from the burst tyre. The intake scoop stuck out like a goose beak. It looked like a car that had worked for a living.

After the summit: museums, myths, and a promise kept

Campbell told the world he would retire when he had done three hundred. He kept his word. Within two years he turned to water and chased records with the same itch for cleaner lines and stronger engines, and with the same faith in a close team. The three hundred run at Bonneville marked the end of a certain kind of motor racing. Men on beaches, strings of shells that sliced tyres, and winds that pushed in gusts gave way to the calm, wide surface of the salt flats.

The Blue Bird itself went on a long afterlife. It was displayed, shipped across oceans, restored, shown again, and now rests at the Motorsports Hall of Fame of America at Daytona International Speedway. At times it has stood at the British National Motor Museum in Beaulieu, alongside the Sunbeam 350 HP that began Campbell’s journey and, in later years, near Donald Campbell’s Bluebird CN7. The details that defined the 1935 car remain striking. The twin rear wheels. The extended intake scoop used at Bonneville. The screw jack points on the flanks. Even the blue paint that became a byword for speed to readers of the period press.

It is easy to focus only on an engine and a headline figure, but the names behind the scenes deserve space. Leo Villa, sleeves rolled, coaxing reliability from complex machinery. Reid Railton, quietly patient, moving weight and air on paper long before metal was cut. Alf Poyser from Rolls Royce, a steady presence in the white overalls seen in Daytona photographs. And then there is the personal echo. Donald Campbell sat in the cockpit in 1933 for photographs, a boy in his father’s seat, before he took his own runs at land and water in later years with triumphs and losses of his own.

Technical stuff for the curious

If you like your numbers neat, here is a useful bundle that tells you what the 1933 and 1935 versions of Blue Bird were really like in the bones.

Powerplant: Rolls Royce R, sixty-degree V-12, double-sided supercharger, bore 152 millimetres, stroke 168 millimetres, displacement about 36.7 litres. In race trim around 2350 horsepower at roughly 3200 rpm and 20 pounds of boost, in special sprint form capable of more.

Transmission and gearing: Three-speed gearbox, ratios in the later car around 2.74 to 1 in first, 1.55 to 1 in second, and direct third. Final drive about 1.19 to 1 in the twin-wheel axle.

Chassis layout: Engine in a subframe within the ladder frame, cockpit offset to the right, prop shaft offset left by about 178 millimetres, left side springs stiffened to resist torque effect.

Cooling and induction: Large forward radiator and sculpted header tank in 1933. In 1935 a full-width radiator behind a slot with a driver-controlled shutter and, crucially, an extended intake scoop projecting forward beyond the radiator outlet to prevent disturbed flow at high speed.

Wheels and tyres: Dunlop tyres on steel rims with aluminium discs, inflated to around 125 psi front and 110 psi rear in the twin-wheel configuration. Each wheel and tyre assembly weighing about 102 kilograms.

Braking: Drum brakes on each wheel at about 457 millimetres in diameter with cooling fins. Additional vacuum-operated air brakes added in 1934 behind the double rear wheels, about 0.19 square metres each.

Dimensions and mass: Wheelbase around 4.19 metres. Overall length about 8.61 metres in 1935. Track roughly 1.52 to 1.60 metres. Mass roughly 4740 kilograms with ballast in 1935.

Cooling capacity: About 136 litres of coolant in 1933 spec. Fuel capacity grew from about 105 litres in the tail to about 182 litres in the left-side tank in 1935.

Every one of those numbers was earned the hard way. A change on paper was a week in the shop. A change in the shop was a day on the beach, and a day on the beach could be a cut tyre or a bent panel. The development curve was not a straight line. It was a rising tide.

If you want to see more, consider planning a visit to Beaulieu’s National Motor Museum [https://nationalmotormuseum.org.uk], the Lakeland Motor Museum [https://www.lakelandmotormuseum.co.uk], or the Motorsports Hall of Fame of America at Daytona [https://www.mshf.com]. You will stand in front of the real thing and the gulf between a page of figures and a long blue car will close in a heartbeat.

Sources:

– The Land Speed Record 1920-1929 by R. M. Clarke (2000)

– Reid Railton: Man of Speed by Karl Ludvigsen (2018)

– The Record Breakers by Leo Villa (1969)

– The Unobtainable: A Story of Blue by David de Lara (2014)

– My Thirty Years of Speed by Malcolm Campbell (1935)

– The Fast Set by Charles Jennings (2004)

– Land Speed Record by Cyril Posthumus and David Tremayne (1971/1985)

– Leap into Legend by Steve Holter (2003)

Excellent story and documentation.