The Gunpowder Plot of 1605: How Robert Catesby and Guy Fawkes Tried to Blow Up Parliament

- Daniel Holland

- Nov 5, 2025

- 12 min read

“Remember, remember, the Fifth of November, Gunpowder treason and plot…”The rhyme may sound like a nursery chant today, but in the winter of 1605 it was a solemn warning, a whispered echo of the day England almost lost its king, its Parliament, and perhaps its very identity.

A Kingdom on Edge

Imagine London before dawn on 5 November 1605. The fog settles over the Thames, and deep beneath the stone chambers of Westminster, a soldier waits. He stands surrounded by barrels hidden under piles of faggots and coal, listening for the bells of morning. The soldier’s name is Guy Fawkes, a Yorkshireman with years of warfare behind him. His orders are simple: guard the powder until the signal is given.

Above his head, the King of England is preparing to open Parliament. Within hours, if the plan holds, King James I, the Lords, the bishops, and the country’s most powerful men will be blown skyward in a single deafening blast.

But Fawkes never lights the fuse. Instead, footsteps echo down the stone passage. Lanterns flash. Hands seize him. And the most daring conspiracy in English history collapses in an instant.

The Seeds of Rebellion

The Gunpowder Plot did not spring from madness. It was the desperate answer of men who felt that hope had betrayed them.

For seventy years, England had been at war with itself over religion. Henry VIII had torn the nation from the Catholic Church. Elizabeth I had built a Protestant state that demanded allegiance to the Crown above all else. Catholics who refused to attend Anglican services were fined, imprisoned, even executed.

When Elizabeth died in 1603, Catholics looked to her successor, James VI of Scotland, with cautious optimism. His mother, Mary Queen of Scots, had died for her faith, and many hoped her son might show mercy. James even promised to “not persecute any that will be quiet and give outward obedience to the law.”

But the promise faded quickly. Within a year he reimposed recusancy fines, banished priests, and filled his court with Protestant ministers. The dream of tolerance curdled into resentment.

Among those who felt the sting of betrayal was Robert Catesby, a charismatic Catholic gentleman, intelligent, educated, and disillusioned. He had once fought for Queen Elizabeth in her wars, but her successor’s policies hardened him. In 1603, he was involved in a small uprising that failed. Now, as he looked upon the unyielding state, he resolved on something that could not fail.

“If we once conceive the deed,” he told his friend Thomas Wintour, “we may bring it to pass. Let us give the attempt, and where it faileth, pass no further.”

The Gathering of the Plotters

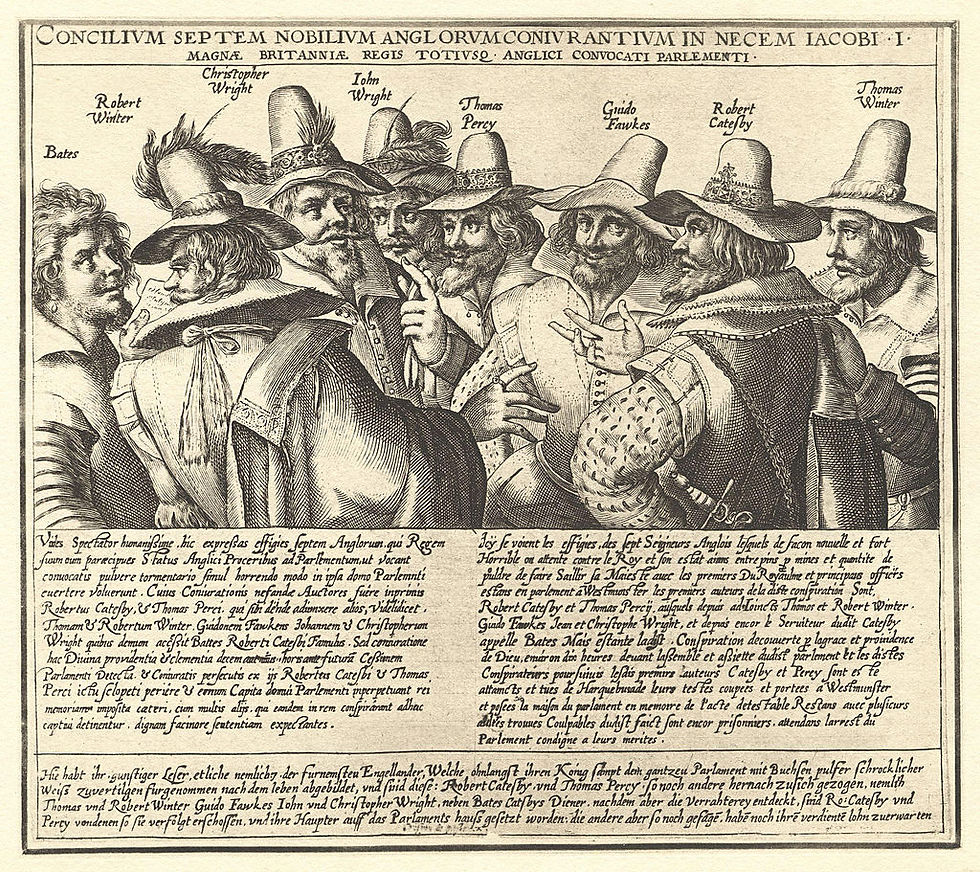

Catesby was the mind, but he needed hands. He gathered a small circle of trusted men—Thomas and Robert Wintour, John and Christopher Wright, Thomas Percy, and a soldier named Guy Fawkes, who had spent years fighting for Catholic Spain. Fawkes’s experience with gunpowder made him indispensable.

In a quiet room in London in May 1604, the men swore an oath of secrecy on a prayer book while, in the next room, a priest named Father John Gerard said Mass.

Their plan was to rent a storeroom beneath the House of Lords, fill it with barrels of powder, and detonate it when the King and Parliament gathered. As chaos tore through the city, they would seize the King’s daughter, nine-year-old Princess Elizabeth, and proclaim her queen under a Catholic protectorate.

By March 1605, the conspirators had rented the undercroft below the House of Lords. It was an unused, dusty cellar filled with firewood, perfect cover for their barrels.

Fawkes, using the name “John Johnson,” took charge of the storehouse, posing as Percy’s servant. Across the river, more barrels were ferried by night from a safe house at Lambeth. In all, thirty-six barrels of powder were rolled into place, enough to level the Palace of Westminster.

A Crisis of Conscience

As the plot took shape, doubts began to stir among the men of faith. Catesby asked Father Henry Garnet, the Jesuit superior in England, whether such a deed, killing the innocent with the guilty, could be justified. Garnet replied that it could “in no case be approved.”

When another priest, Father Oswald Tesimond, heard of the plot in confession, he informed Garnet but refused to betray the secret. Garnet urged him to dissuade Catesby, but the young zealot would not be moved. The King, he argued, had broken his word. “Let the whole realm be set aflame,” he said, “if only the true faith might rise from the ashes.”

The Monteagle Letter

By late October, everything was ready. The barrels lay waiting beneath Westminster. Fawkes would strike the spark, then escape across the Thames as Parliament vanished in a cloud of dust and flame.

But fate, perhaps carelessness, intervened.

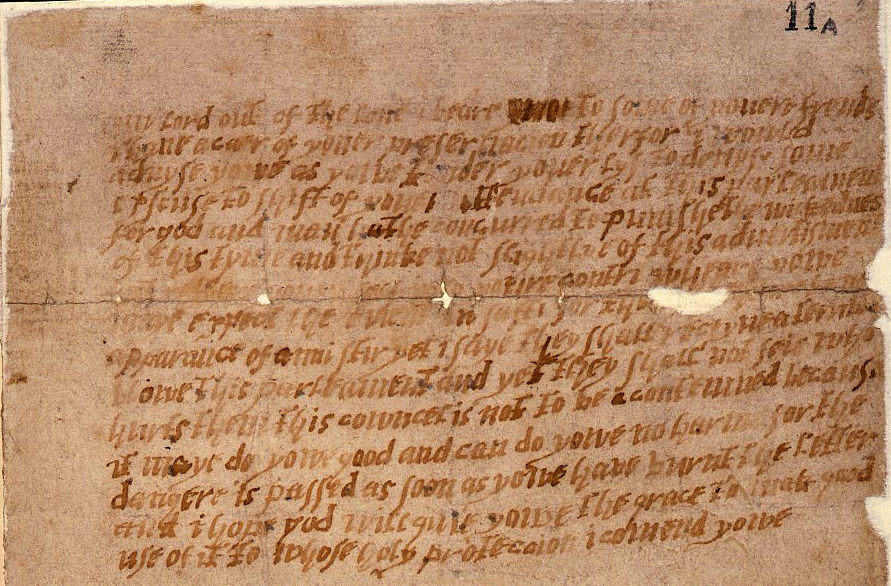

On 26 October 1605, a mysterious letter was delivered to William Parker, fourth Baron Monteagle, a Catholic nobleman. Its warning was clear:

“My Lord, out of the love I bear to some of your friends, I have a care of your preservation... For though there be no appearance of any stir, yet I say they shall receive a terrible blow this Parliament, and yet they shall not see who hurts them.”

Monteagle, alarmed, took the letter straight to the King’s chief minister, Robert Cecil. When James himself read it, he seized upon the phrase “a terrible blow.” His father, Lord Darnley, had been murdered by gunpowder decades earlier. He recognised the danger instantly.

The Discovery

On the evening of 4 November, the King’s men began their search. At first, they found nothing but stacks of timber. But when Sir Thomas Knyvet returned around midnight, his men discovered a cloaked figure with a lantern, a pocket watch, and matches. Beneath the firewood lay the powder.

Guy Fawkes was arrested on the spot. Brought before the King, he gave his name as “John Johnson” and showed no fear. “You would have blown me up, your King, and all my kingdom?” James asked. “Yes,” Fawkes answered calmly, “if I had but been within reach of the match.” The King, half in admiration, remarked on the prisoner’s “Roman resolution.”

But the government wanted names. Fawkes was taken to the Tower of London and locked in a cold cell. A royal order authorised “gentler tortures first, and so by degrees to the worse.”

Interrogation in the Tower

The Tower of London was no stranger to pain. The lower vaults beneath the White Tower, with their dripping walls and manacles, were reserved for the accused of high treason.

Fawkes was initially restrained by handcuffs and chains, deprived of sleep, and questioned for hours by candlelight. When he remained silent, the Lieutenant of the Tower produced the royal warrant signed by the King himself. Fawkes read it in silence, knowing what it meant.

Over the next two days, he endured a series of interrogations. The rack, a wooden frame that stretched the body inch by inch, was used sparingly in England, but with royal permission, it was brought forth for Fawkes.

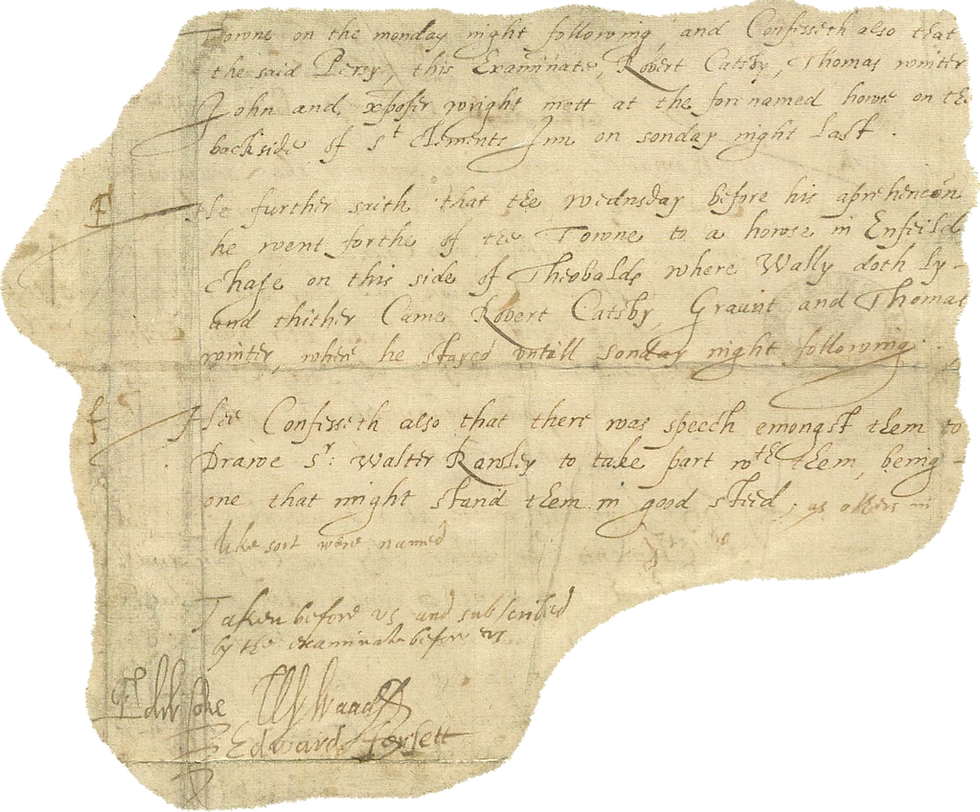

The guards recorded that after “a night of suffering,” his defiance faded. His signature on his first confession is a mere scrawl, barely a line, trembling and broken. In that confession, dated 7 November, he named his accomplices and described the cellar, the barrels, and the plan to crown Princess Elizabeth.

His confession began:

“After I was taken and examined, I confessed the intention was to have blown up the King and Parliament, and that my purpose was to have set fire to the powder with a match about long enough to have given me time to escape.”

“Gentle tortures” had done what persuasion could not.

His statements were published weeks later in The King’s Book, ensuring that every subject in England would read how divine providence had saved the realm from fire and ruin.

The Flight and Final Stand

While Fawkes languished in the Tower, Catesby and the others fled through the Midlands, hoping to rally a Catholic uprising. None came. Villagers shut their doors. Priests refused to bless them.

At Holbeche House in Staffordshire, they made a last stand. In a desperate attempt to dry their damp powder, sparks from the hearth ignited it, wounding several. At dawn, the Sheriff of Worcestershire surrounded the house.

Gunfire thundered across the courtyard. John and Christopher Wright fell first, then Rookwood. Catesby and Percy were struck by a single musket shot that pierced them both. As they lay dying, Catesby clutched a picture of the Virgin Mary to his chest and whispered, “We intended to do her service.”

The Trial

The surviving conspirators, Thomas and Robert Wintour, Ambrose Rookwood, Sir Everard Digby, Thomas Bates, Robert Keyes, and Guy Fawkes, were tried at Westminster Hall in January 1606. The King and royal family watched from behind a screen.

Sir Edward Coke, the Attorney General, thundered that “I never yet knew a treason without a Romish priest; but in this there are very many Jesuits who have dealt and passed through the whole action.”

The accused were condemned to die as traitors. Coke recited the ancient sentence in full, a piece of theatre as cruel as it was deliberate. He described how each man would be drawn backwards to his death, by a horse, his head near the ground. He was to be "put to death halfway between heaven and earth as unworthy of both". His genitals would be cut off and burnt before his eyes, and his bowels and heart then removed. Then he would be decapitated, and the dismembered parts of his body displayed so that they might become "prey for the fowls of the air", and “put to death halfway between heaven and earth, as unworthy of both.” It was not only a punishment but a performance, a reminder of what awaited those who betrayed the Crown.

The Executions

On 30 January, four of the conspirators (Digby, Robert Wintour, John Grant, and Thomas Bates) were taken from the Tower to St Paul’s Churchyard. The following day, the rest (Thomas Wintour, Ambrose Rookwood, Robert Keyes, and Guy Fawkes) were brought to Old Palace Yard, within sight of the very building they had planned to destroy.

A crowd pressed close as the prisoners arrived, some jeering, some praying. Digby asked forgiveness from the spectators and thanked God “that I die for the Catholic faith.” He was stripped of his clothing, and wearing only a shirt, climbed the ladder to place his head through the noose. He was quickly cut down, and while still fully conscious was castrated, disembowelled, and then quartered, along with the three other prisoners.

Guy Fawkes was the last to climb the scaffold. Weak and shaking from his weeks in the Tower, he steadied himself against the ladder. Witnesses said he faced the crowd without fear. One chronicler wrote, “He seemed to scorn the torment, as one whose courage failed him not even to the end.”

Then, with one final act of defiance, he leapt from the platform, ensuring his neck broke instantly, sparing himself the lingering cruelty of what was to follow. The crowd gasped, and the Sheriff declared the law satisfied.

The body of Guy Fawkes was quartered, his remains sent to the four corners of the kingdom as a warning. The others met similar ends. The government had not only avenged itself, it had written a lasting lesson in loyalty.

Faith, Fire and Aftermath

In the weeks that followed, England erupted in thanksgiving. Church bells rang across the land. Parliament passed the Observance of 5th November Act, declaring the day a perpetual celebration of divine deliverance.

Henry Garnet, accused of knowing the plot in confession, was later captured, tried, and executed. When threatened with torture, he replied, “Minare ista pueris”—“Threaten that to boys.” His dignity impressed even his judges.

For English Catholics, the Gunpowder Plot was a disaster beyond measure. Any remaining hopes for tolerance were extinguished. Catholics were now seen as traitors by association, and the harsh penalties for recusancy deepened.

Bonfire Night and the Making of a Legend

In 1606, just months after the executions, Parliament passed a new law to mark what it saw as divine deliverance. Officially titled “An Act for a Public Thanksgiving to Almighty God every Year on the Fifth Day of November,” it demanded that every parish in England hold annual church services of thanksgiving and light great bonfires “in remembrance of the joyful day of deliverance.”

What began as a solemn ritual of national survival gradually turned into a celebration. Bonfires flared in city squares and village greens, fireworks lit the skies, and the day became known by many names — Guy Fawkes Night, Plot Night, Fireworks Night — each echoing the failed conspiracy that had almost ended the monarchy.

Immortalising Fawkes

Robert Catesby had been the leader of the Gunpowder Plot, but it was Guy Fawkes, the man caught in the act, lantern in hand, who became the face of it. His name lingered in English memory, twisted over centuries from villain to folk figure.

By the late eighteenth century, Fawkes had taken on a new afterlife. Effigies of him were burned on bonfires as early as 1790, the flames transforming him from traitor to tradition. Crowds gathered to cheer, jeer, and toss straw “Guys” into the fire, a symbolic act of purging treason, or perhaps of keeping it alive in memory.

“A Penny for the Guy”

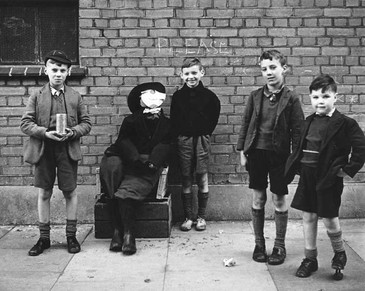

By the nineteenth century, children had made the story their own. In the days leading up to 5 November, they cobbled together figures of Fawkes from whatever they could find, old clothes stuffed with straw, pillows, newspapers, battered hats and boots.

These homemade “Guys” were paraded through the streets on prams, barrows, or wooden carts while children called out, “Penny for the Guy?” The coins collected were meant to buy fireworks, though often they went toward sweets or pocket money.

When night fell, the effigies were fed to the flames. Smoke, sparks, and laughter filled the air — the ancient warning transformed into carnival. Though the custom has faded in many places, replaced by Halloween’s American imports, its echo remains in the glow of every bonfire that still burns on 5 November.

From Villain to Anti-Hero

Fawkes’s image softened over time. The turning point came with William Harrison Ainsworth’s 1841 historical novel Guy Fawkes: or, The Gunpowder Treason, which reimagined the conspirator not as a villain, but as a tragic, almost romantic figure, driven by faith, betrayed by fate.

The novel’s success owed much to its vivid illustrations by George Cruikshank, the caricaturist who also worked with Charles Dickens. Cruikshank’s engravings brought to life the dungeon scenes, the plotting in shadowed chambers, and Fawkes’s defiant bearing under interrogation. Our collective imagination still borrows from those images, the dark cloaks, the coiled fuse, the watchful eyes in the gloom.

Ainsworth’s version of Fawkes became a fixture of popular culture, inspiring plays, penny novels, and even early children’s books. He was no longer merely a traitor; he was a man at odds with power, misguided, perhaps, but recognisably human.

A Symbol of Resistance

Centuries later, the name “Guy Fawkes” would ignite once again, this time not in Westminster, but in art, film, and protest.

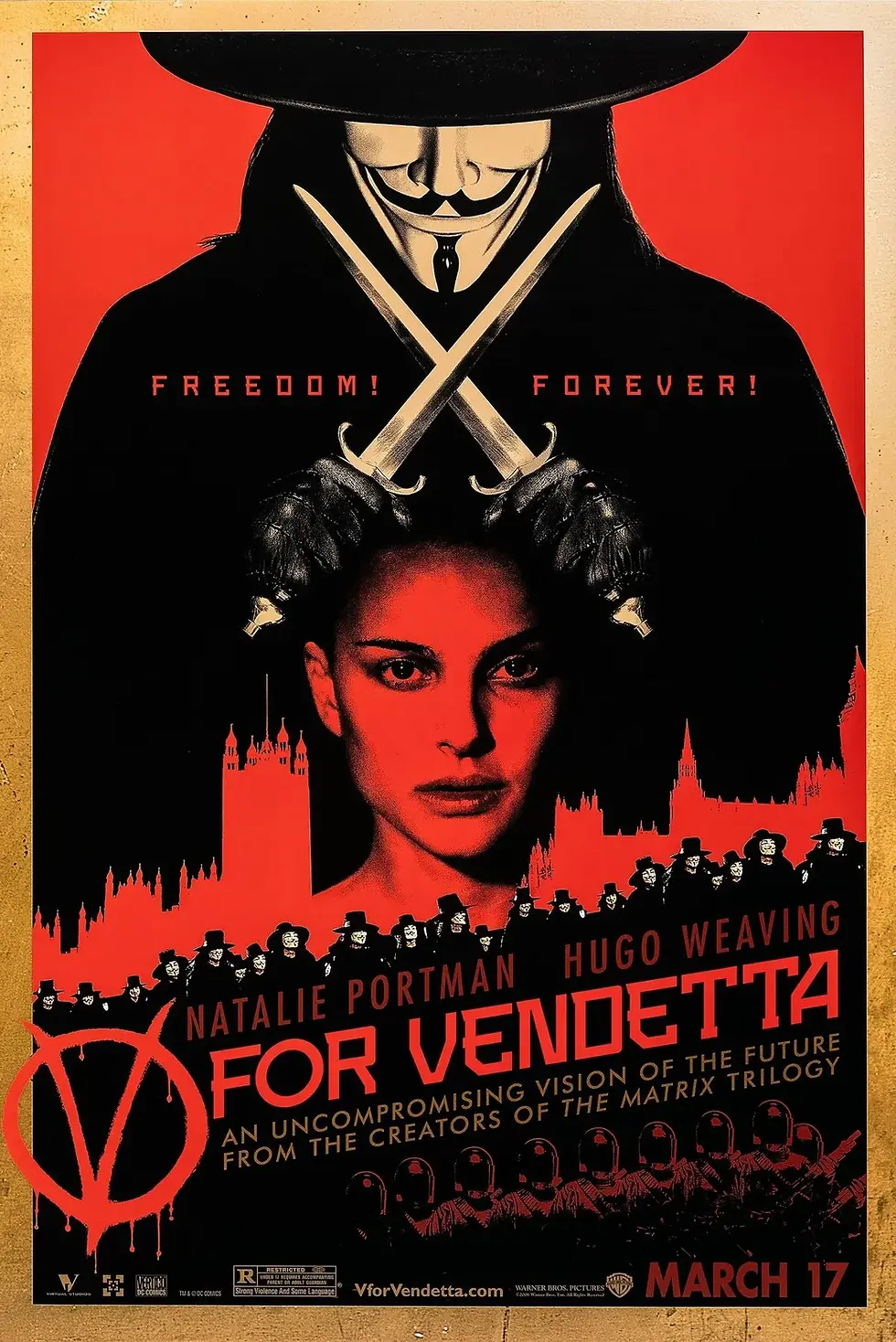

In 1988, Alan Moore and illustrator David Lloyd created V for Vendetta, a graphic novel set in a dystopian Britain ruled by tyranny. Its hero, known only as “V,” dons a stylised Guy Fawkes mask to conceal his face as he fights against the state. The mask, with its faint smile and knowing eyes, was designed, in Lloyd’s words, “to adopt the persona and mission of Guy Fawkes, our great historical revolutionary.”

The symbol caught fire. When the film adaptation was released in 2005, the mask became a global icon. Protesters from Occupy Wall Street to Anonymous rallies wore it as a badge of resistance — an emblem of defiance against corruption and control.

In this strange afterlife, the man who failed to destroy Parliament became the face of rebellion against power itself. Four hundred years after his arrest, Guy Fawkes still stands in the flicker of firelight — not just as the man who was caught, but as the idea that refuses to burn away.

Legacy of the Plot

The Gunpowder Plot changed England forever. It reinforced the Crown’s authority, hardened anti-Catholic laws, and gave the state a myth of divine protection that endured for centuries.

Shakespeare wrote Macbeth soon after, weaving its unease into a line about “the equivocator, who committed treason enough for God’s sake.” John Milton later described the conspiracy as a “horror without a name.”

Today, only the fireworks remain, a sparkling echo of the explosion that never came. But beneath the noise and the smoke lies the memory of a single night when England stood a breath away from catastrophe, and the calm, cold voice of a man in a cellar saying that, yes, he would have done it “if he had but been within reach of the match.”

Sources:

Encyclopaedia Britannica: Gunpowder Plot – https://www.britannica.com/event/Gunpowder-Plot

UK Parliament: The Gunpowder Plot of 1605 – https://www.parliament.uk/about/living-heritage/evolutionofparliament/parliamentary-authority/the-gunpowder-plot-of-1605/

Royal Museums Greenwich: Gunpowder Plot: What Is the History Behind Bonfire Night? – https://www.rmg.co.uk/stories/topics/gunpowder-plot-history-bonfire-night

The National Archives: Gunpowder Plot Resources – https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/resources/gunpowder-plot/

British Library: The Monteagle Letter – https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/the-monteagle-letter

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography – Robert Catesby, Guy Fawkes, Henry Garnet

Comments