Martin Gusinde and the Vanishing Worlds of Tierra del Fuego

- Daniel Holland

- Nov 8, 2025

- 8 min read

Between 1918 and 1924, a quiet Austrian priest named Martin Gusinde undertook a journey to the farthest reaches of the inhabited world. His destination was Tierra del Fuego, the windswept archipelago at the southern tip of South America, where three Indigenous groups—the Selk’nam (also known as Ona), the Yamana (or Yaghan), and the Kawésqar (Alacalufe)—were living out their final generations of traditional life. By the time Gusinde arrived, these societies had already been decimated by colonial expansion, disease, and displacement. What he captured during his four journeys between 1918 and 1924, however, would become one of the most important ethnographic records of its kind: a collection of over 1,200 photographs, songs, and detailed notes that offered the last comprehensive window into these unique cultures.

His story is not merely that of a missionary encountering distant peoples. It is also one of profound cultural immersion, empathy, and documentation carried out at the edge of the modern world, an attempt to preserve what colonial modernity had almost entirely erased.

Early Life and Calling

Martin Gusinde was born in Breslau (then part of the German Empire, now Wrocław, Poland) in 1886. In 1900, at just fourteen years old, he joined the Society of the Divine Word, a missionary order with a strong emphasis on linguistics, ethnology, and cross-cultural education. He began higher studies in 1905 at St. Gabriel’s Mission House in Mödling, near Vienna, a centre known for training missionary scholars in anthropology and linguistics.

Ordained in 1911, Gusinde was sent to Chile, a destination that would shape the course of his life’s work. Initially, he served as a teacher, but by 1913 he had joined the Ethnographic Museum in Santiago under the direction of the eminent German archaeologist Max Uhle. The museum, at the time, was one of Latin America’s most dynamic institutions for ethnological study, documenting the vast diversity of the continent’s Indigenous cultures.

By 1918, Gusinde had become head of the museum’s ethnology department. But while many scholars were content to study artefacts and specimens from afar, he was drawn to the field itself—to the people whose traditions were on the brink of extinction.

The Call to Tierra del Fuego

The islands of Tierra del Fuego had long held a near-mythical status among Europeans: a land of perpetual cold and isolation, where seafaring tribes navigated channels in canoes and where elaborate rituals honoured ancestral spirits. The Fuegians, as they were called by outsiders, had been described by Charles Darwin during the voyage of the Beagle as “the most curious and interesting inhabitants of the world.” But by the early 20th century, their numbers had been devastated by waves of colonisation and the violent expansion of sheep farming.

By 1880, the Selk’nam were being systematically hunted by ranchers and bounty hunters, their lands seized for grazing. Diseases brought by Europeans (measles, tuberculosis, and influenza) further decimated the population. Missionary records from the late 19th century spoke of entire families dying within weeks of contact. By the time Gusinde made his first journey south in 1918, the Selk’nam and Yamana were cultural remnants, their languages and rituals clinging to survival among a few dozen elders.

It was into this world that Gusinde ventured, determined to learn, record, and understand.

Four Journeys at the End of the Earth

Over six years, Gusinde made four expeditions to Tierra del Fuego, spending a total of twenty-two months in the field. His approach was one of deep immersion rather than distant observation. He lived among the people he studied, learned their languages, participated in their ceremonies, and, remarkably, was initiated into the Selk’nam Hain—a sacred male initiation ritual few outsiders had ever witnessed.

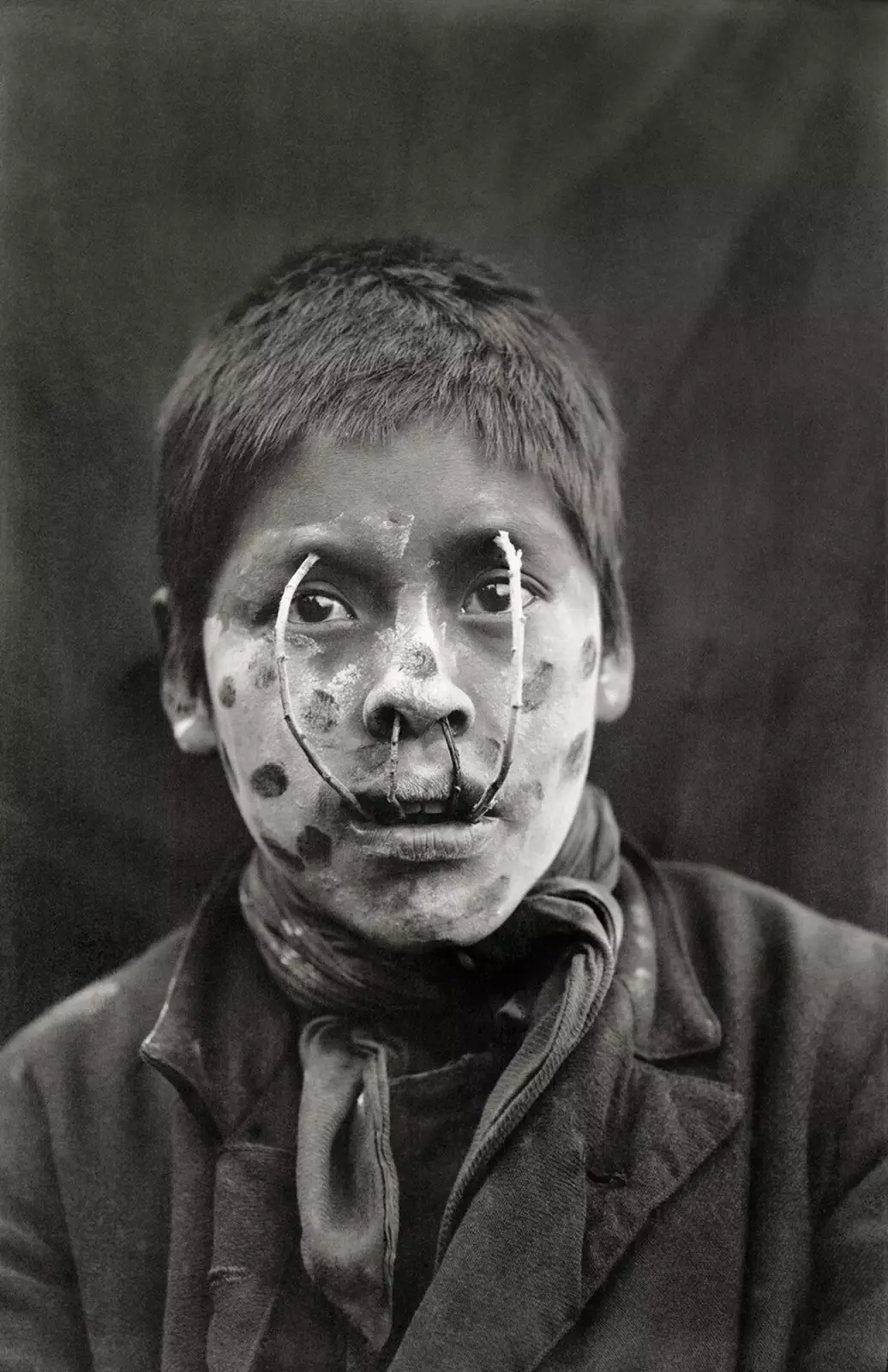

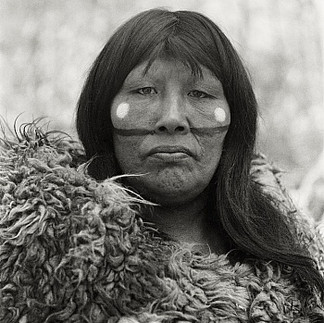

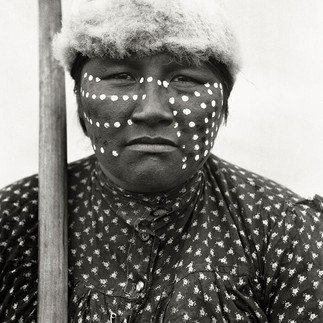

The Hain was not merely a rite of passage but a complex theatrical ceremony embodying the cosmology and social order of Selk’nam life. Participants, painted in striking geometric body patterns and masked as ancestral spirits, re-enacted the mythological struggles that defined their universe. Gusinde’s participation was unprecedented. His acceptance into the ritual testified to his humility and willingness to live as they did—sharing their food, enduring the same weather, and respecting their beliefs.

His photographs from this period are extraordinary. They show men painted head to toe in white, black, and red, transformed into spirits with elongated faces and haunting expressions. Others depict women and children at the margins of these ceremonies, and scenes of daily life—canoes, camps, and gatherings, that reveal a community still bound by ancestral tradition despite colonial pressures.

Gusinde’s photography stands apart from most missionary or colonial imagery of the era. Rather than portraying the Fuegians as curiosities or as vanishing primitives, he captured them as individuals—dignified, expressive, and fully human. His portraits convey a sense of collaboration: subjects look directly at the camera, aware of their participation in a shared project of memory.

A Missionary Ethnologist

Though a missionary by training, Gusinde’s ethnographic work was guided less by conversion than by comprehension. He believed that understanding human diversity deepened faith rather than threatened it. “Every people,” he wrote, “bears within itself a reflection of the divine image.”

His academic rigour set him apart from many contemporaries. Working on behalf of the Berlin Phonogram Archive, he made some of the earliest sound recordings of Yamana and Selk’nam songs—chants of creation, healing, and mourning—preserving voices that would soon be silenced. These wax cylinder recordings, still housed in European archives, are among the few surviving traces of these languages spoken fluently.

Upon returning to Vienna, Gusinde completed his doctorate in anthropology in 1926. He continued to collaborate internationally, helping edit and publish a Yamana-English dictionary based on the manuscript of Reverend Thomas Bridges, an Anglican missionary who had lived among the Yamana in the late 19th century. The dictionary, published in 1933 with Ferdinand Hestermann, became a cornerstone for later linguistic revival efforts.

From South America to Africa and Oceania

Gusinde’s ethnographic curiosity did not end in South America. During the 1930s, he travelled to the Congo to study the Mbuti and other forest-dwelling peoples, at a time when European anthropology was increasingly turning toward questions of human origins and physical variation. His field notes and comparative analyses contributed to early discussions of cultural adaptation to environment, a theme that would later inform ecological anthropology.

After the Second World War, Gusinde’s career took him across continents. Between 1949 and 1957, he taught at The Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C., where he shared his insights into cross-cultural understanding and religious anthropology. Even in his sixties, his fieldwork continued: in 1956, he led an expedition to New Guinea to study the Ayom pygmies, again emphasising the importance of first-hand engagement.

Later, between 1959 and 1960, he taught at Nanzan University in Nagoya, Japan, further extending his influence as a teacher and scholar. Eventually, he returned to Austria, where he lived at the Mission St. Gabriel in Maria Enzersdorf, continuing to write and teach until his death in 1969.

The Photographs as Testament

The 1,200 photographs Gusinde brought back from Tierra del Fuego remain some of the most significant ethnographic images ever taken. Preserved today in European archives and exhibited in museums, they offer an irreplaceable record of cultures that were already on the brink of disappearance when he encountered them.

Among the most haunting are the images from the Hain ceremony, in which figures painted in elaborate designs represent spirits such as Xalpen and Halaháches. These photographs, often staged with the cooperation of the participants, blend ethnography with artistry. The visual compositions, figures emerging from shadow, faces framed by the landscape, convey both the beauty and fragility of a world soon to be lost.

In later years, critics would debate whether Gusinde’s work could truly escape the colonial gaze of its era. Yet his field diaries suggest an unusual degree of respect. He often expressed sorrow at the suffering he witnessed, describing the Selk’nam as “a noble people reduced to despair.” He condemned the violence inflicted by settlers and the indifference of the Chilean state. His tone was not that of a conqueror or collector, but of a witness attempting to record the last echo of a vanishing humanity.

A Legacy of Preservation and Reflection

By the time Gusinde published his major ethnographic studies in the 1930s and 1940s, the peoples of Tierra del Fuego had nearly disappeared as distinct societies. Yet his work became a foundation for future generations of anthropologists and ethnomusicologists. The linguistic, musical, and visual records he left behind have since informed cultural revival efforts in southern Chile and Argentina, where descendants of the Yamana and Selk’nam continue to reclaim their heritage.

In 2015, the Chilean government officially recognised the Selk’nam as one of the country’s Indigenous peoples, a symbolic act of survival that owes much to the historical evidence Gusinde helped preserve.

His approach also anticipated what would later be termed “participant observation,” a method that became central to modern anthropology. By living among the people he studied rather than merely observing them, he set a precedent for empathy-driven research.

The Singular Vision of Martin Gusinde

What makes Gusinde’s work stand out, even today, is the singularity of his approach. He travelled to one of the most remote regions on Earth, at a time when communication with Europe took months, and immersed himself completely in a culture that no longer exists in its original form. His isolation, spiritual as much as geographical, gave his work a profound sense of purpose.

While many early ethnographers sought to classify or “civilise,” Gusinde sought to understand. His mission, paradoxically, was not to convert but to conserve. The beauty of his photographs lies in this tension: the missionary who came to spread the Word instead ended up preserving the voices of those who would otherwise have been silenced.

Final Years and Reflection

After returning permanently to Austria, Gusinde lived quietly at St. Gabriel’s, surrounded by the notes, wax cylinders, and photographs that bore witness to his life’s work. He never married and remained devoted to teaching and writing until his death on 10 October 1969 in Mödling.

His collections now reside in archives such as the Anthropos Institute and the Martin Gusinde Museum in Puerto Williams, Chile, the southernmost museum in the world. These institutions ensure that the cultures he documented are not forgotten, even as the winds of Tierra del Fuego continue to sweep across the lands where the Yamana once built their canoes and the Selk’nam painted their bodies for the Hain.

Legacy and Influence

Martin Gusinde’s work endures as both a scientific achievement and a moral document. His meticulous ethnographies—blending theology, anthropology, and photography—reveal a scholar profoundly committed to human diversity. Today, exhibitions of his photographs, such as The Lost Tribes of Tierra del Fuego shown in major European museums, continue to captivate audiences, not for their exoticism but for their humanity.

In an age when Indigenous cultures across the world face new forms of displacement and erasure, Gusinde’s efforts remind us of the importance of witness. He once wrote that “the beauty of man lies in his multiplicity, in his capacity to reflect God in countless forms.” Through his lens and his pen, he preserved some of those forms for all time.

Sources:

“Martin Gusinde.” Ethnological Museum of Berlin. https://www.smb.museum/en/museums-institutions/ethnologisches-museum/

Gusinde, Martin. The Yamana: The Life and Thought of the Water Nomads of Cape Horn. Smithsonian Institution Press, 1991.

Bridges, Thomas. Yamana-English Dictionary, edited by Martin Gusinde and Ferdinand Hestermann, 1933.

Lenz, Hans. Gusinde, el Misionero Etnólogo. Santiago de Chile, 1969.

Museo Antropológico Martin Gusinde, Puerto Williams, Chile. https://www.museogusinde.cl/

Comments