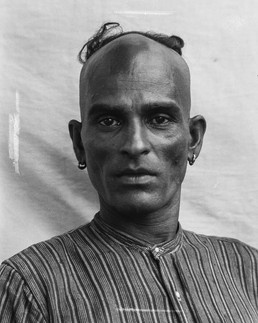

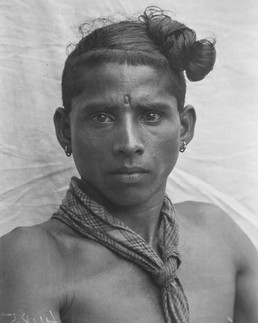

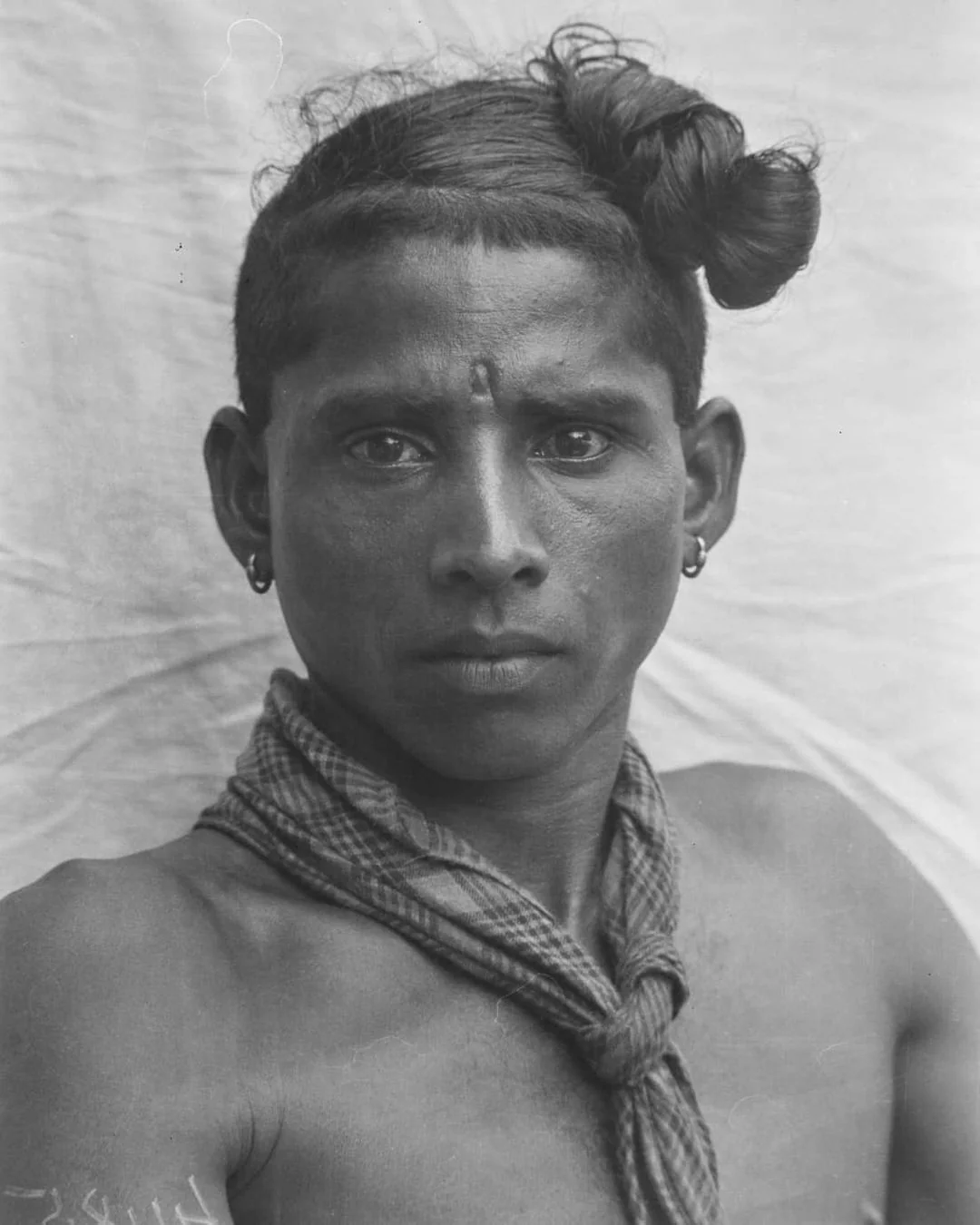

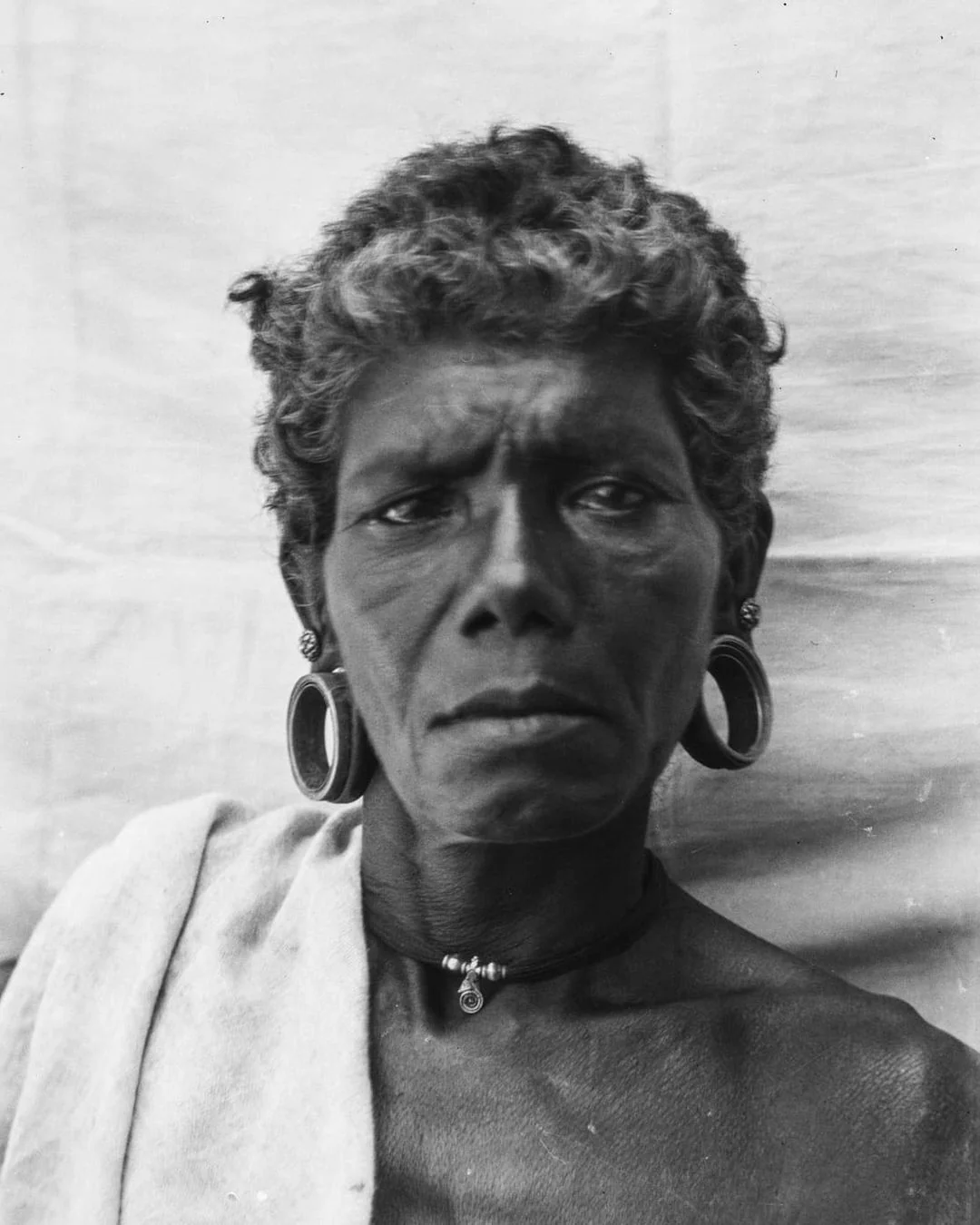

Portraits of People in Kerala, India Taken by Egon von Eickstedt in the 1920s

- Daniel Holland

- Aug 27, 2025

- 4 min read

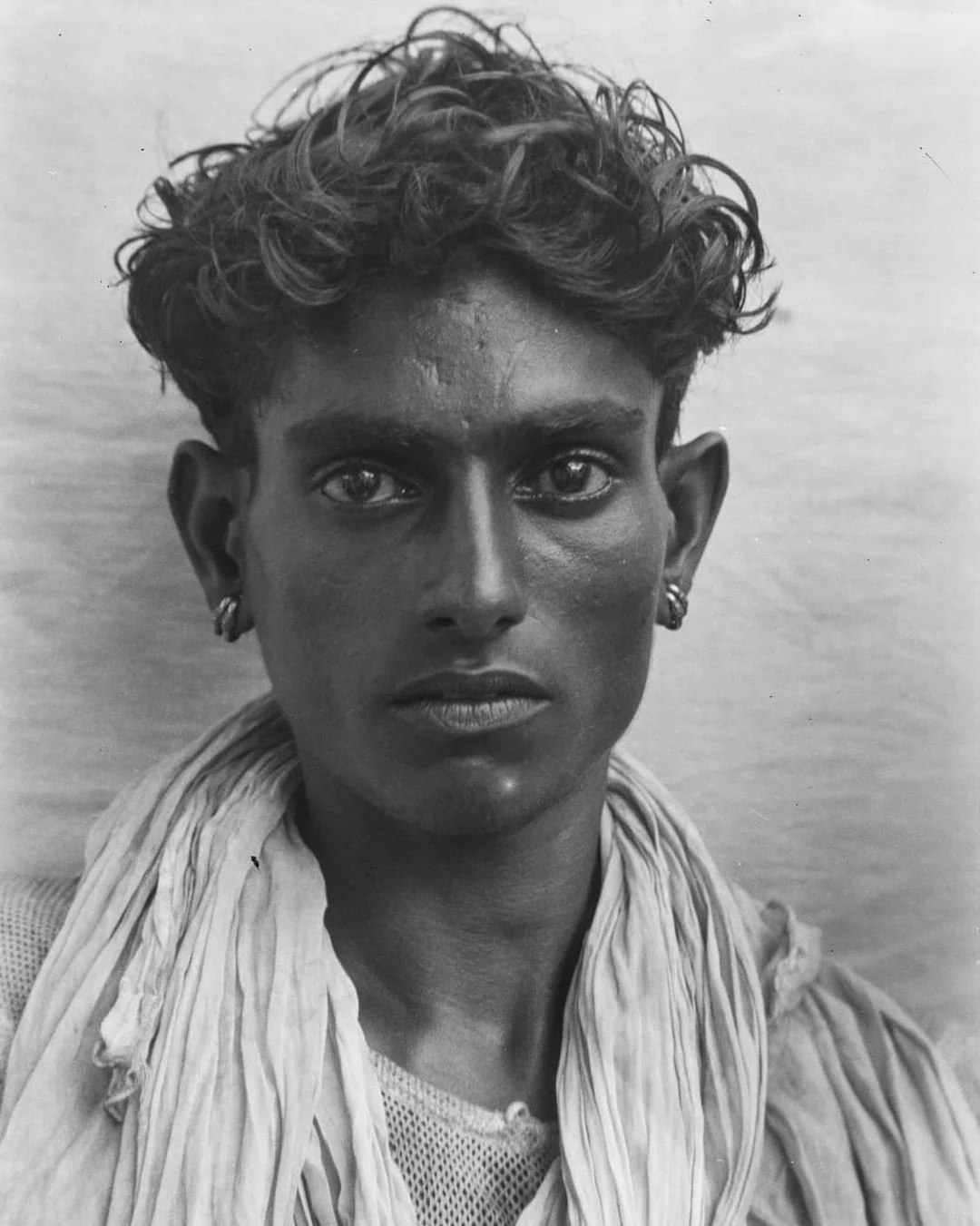

In the humid landscapes of Kerala during the 1920s, villagers and Adivasi communities found themselves before the camera lens of a German anthropologist named Egon von Eickstedt. His portraits, stark and carefully posed, were not made with the artistic intentions of a photographer in search of beauty, but rather as part of an ambitious project to classify humanity itself.

Between 1926 and 1929, Eickstedt travelled through India, Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), and Burma (Myanmar). His expeditions yielded around 12,000 photographs and 2,000 collected objects, forming a massive archive of visual and material culture. Among these images are striking portraits of people from Kerala, particularly from indigenous and Dalit communities, whom he considered central to his studies.

Who Was Egon von Eickstedt?

Eickstedt (1892–1965) was a German physical anthropologist who dedicated much of his career to measuring, photographing, and categorising human populations. His methods included anthropometry, measuring skulls, bodies, and facial features, alongside photography, which he believed could serve as a scientific record of racial traits.

His main intellectual project was to write a “racial history of mankind.” In his monumental work, Rassenkunde und Rassengeschichte der Menschheit (Ethnology and the Race History of Mankind), he divided humanity into racial categories, attempting to map out how different “types” had evolved and spread.

Though his expeditions to South Asia took place before his affiliation with Nazi Germany, Eickstedt would later become a significant racial theorist under the Third Reich. His earlier fieldwork, including the portraits taken in Kerala, was retroactively folded into this racial ideology.

Portraits from Kerala

In Kerala, Eickstedt’s camera turned toward Adivasi groups and Dalit communities. His portraits typically depict individuals in isolation, often staring directly at the lens, stripped of their everyday context. Men, women, and children appear against neutral backgrounds or in carefully arranged poses, as if they were specimens rather than people with lives, emotions, and stories.

Egon von Eickstedt’s 1920s photographs of indigenous people in Kerala, South India

For Eickstedt, the photographs were never simply portraits. They were data points. His intention was to use photography as evidence of what he saw as “primitive peoples” and their place in human evolution. He was fascinated by what he considered to be “original” cultural practices, which he believed were preserved in India’s indigenous communities.

From today’s perspective, these images carry a dual weight: on one hand, they provide some of the earliest photographic documentation of communities in Kerala during the 1920s. On the other, they are framed by an anthropological gaze shaped by colonialism and racial hierarchy.

Anthropological portraits of Kerala’s communities captured by Egon von Eickstedt between 1926 and 1929.

The Scale of His Collection

Eickstedt’s three-year expedition was immense in scope. By the end, he had produced:

12,000 photographic images, ranging from portraits to scenes of cultural practices.

2,000 ethnographic objects, including clothing, tools, and ritual items.

Thousands of anthropometric measurements, sketches, and notes.

These materials were shipped back to Germany, where they became part of museum and academic collections. They reinforced Eickstedt’s vision of human diversity as something that could be catalogued, sorted, and hierarchised.

Anthropology in a Colonial Frame

The 1920s were a turning point in anthropology. While some anthropologists were beginning to focus on participant observation and cultural relativism, others — like Eickstedt — were still deeply rooted in the racial science traditions of the 19th century.

Egon von Eickstedt’s 1920s photographs of indigenous people in Kerala, South India

Colonial power shaped these encounters. The people of Kerala did not invite Eickstedt to photograph or measure them; they were participants in a project that positioned them as “subjects of study.” Their portraits, while humanising to modern eyes, were created in a context of profound asymmetry: the anthropologist controlled the gaze, the camera, and ultimately the narrative.

Legacy and Controversy

Eickstedt’s later career casts a shadow over his early expeditions. As Nazi Germany rose to power, he became one of its most prominent racial theorists. His work in India and beyond was cited as “scientific proof” of racial hierarchies, even though his theories were shaped as much by ideology as by data.

Anthropological portraits of Kerala’s communities captured by Egon von Eickstedt between 1926 and 1929.

Today, his photographs are valuable records of cultural history, but they cannot be divorced from the context in which they were created. For scholars and descendants of the communities he photographed, the images are often viewed through a critical lens, as archives of both visibility and exploitation.

They tell us as much about European ambitions to categorise the world as they do about the people who appear in them.

Anthropological portraits of Kerala’s communities captured by Egon von Eickstedt between 1926 and 1929.

Why They Still Matter

Despite their troubling origins, Eickstedt’s portraits of Kerala continue to surface in museum collections, academic studies, and digital archives. They matter for several reasons:

Historical record: They preserve visual documentation of communities in Kerala nearly a century ago.

Critical reflection: They highlight the entanglement of anthropology, colonialism, and race science.

Personal heritage: For descendants, the images may serve as rare visual traces of ancestors otherwise absent from written history.

In looking at them today, we are confronted with two histories at once: the lived realities of Kerala’s indigenous people, and the European urge to classify, control, and define them.

Egon von Eickstedt’s 1920s photographs of indigenous people in Kerala, South India

Conclusion

The portraits taken by Egon von Eickstedt in Kerala during the 1920s are striking, but they are also unsettling. They remind us that anthropology was once driven less by understanding and more by categorisation.

For the people of Kerala, these photographs freeze moments of dignity, presence, and humanity, even as the context in which they were made attempted to reduce them to racial “types.” For us, they stand as a reminder of the complicated legacies of science, empire, and memory.

Egon von Eickstedt’s 1920s photographs of indigenous people in Kerala, South India

Sources

University of Göttingen – Collections of Egon von Eickstedt

https://www.uni-goettingen.de/en/egon-von-eickstedt-collection/

Subrahmanyam, Sanjay. Europe’s India: Words, People, Empires, 1500–1800. Harvard University Press, 2017.

Nipperdey, Justus. “Egon von Eickstedt and the Racial Sciences in India.” History and Anthropology, Vol. 25, No. 3, 2014.

Smithsonian Institution – Anthropological Photographic Collections

Eickstedt, Egon von. Rassenkunde und Rassengeschichte der Menschheit. Stuttgart: Enke, 1934.