Ivan Aivazovsky and His Miniature Masterpieces: The Romantic Painter Who Turned Self-Promotion into Art

- Daniel Holland

- Oct 14, 2025

- 6 min read

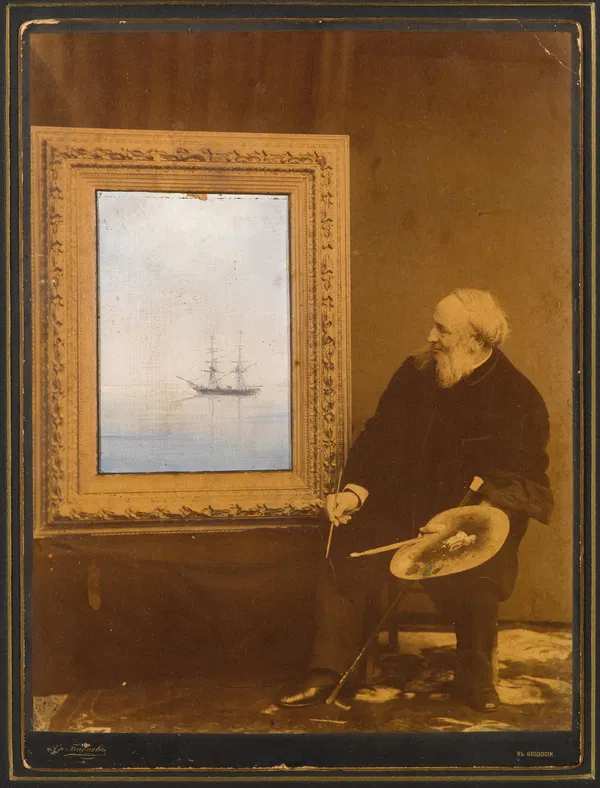

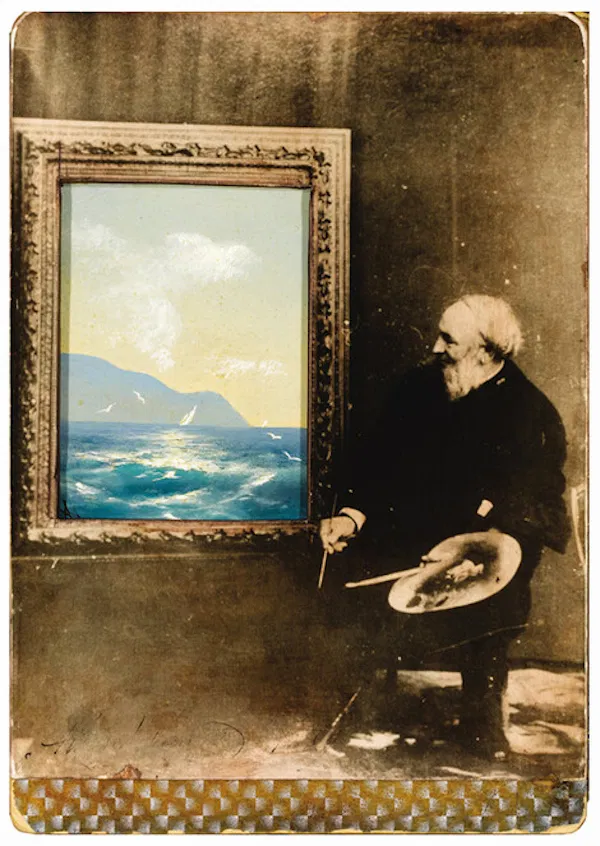

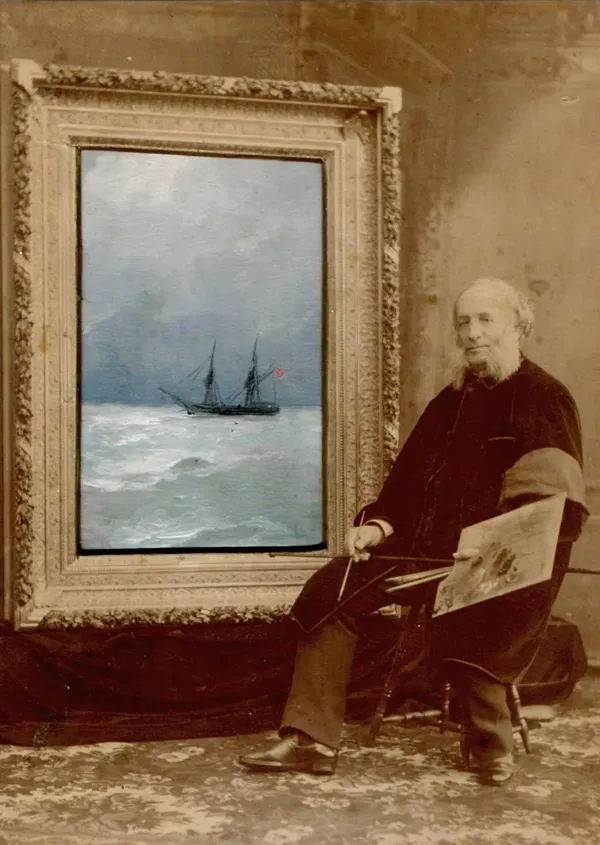

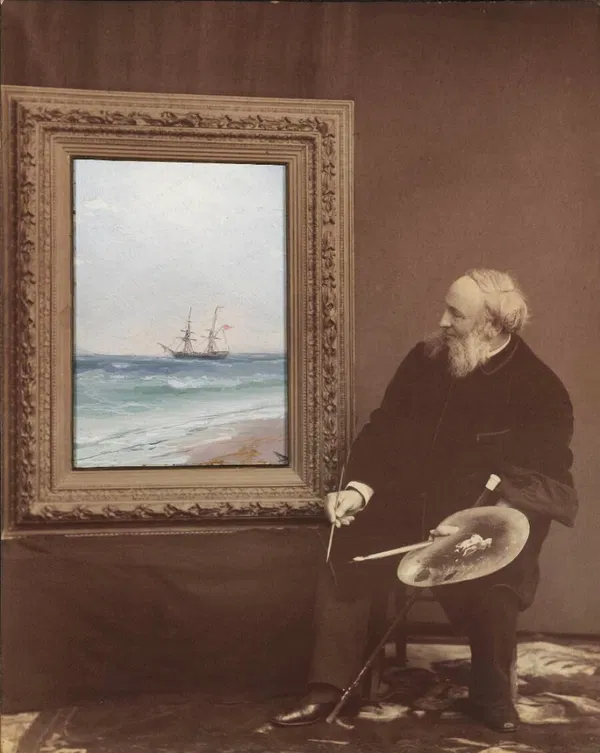

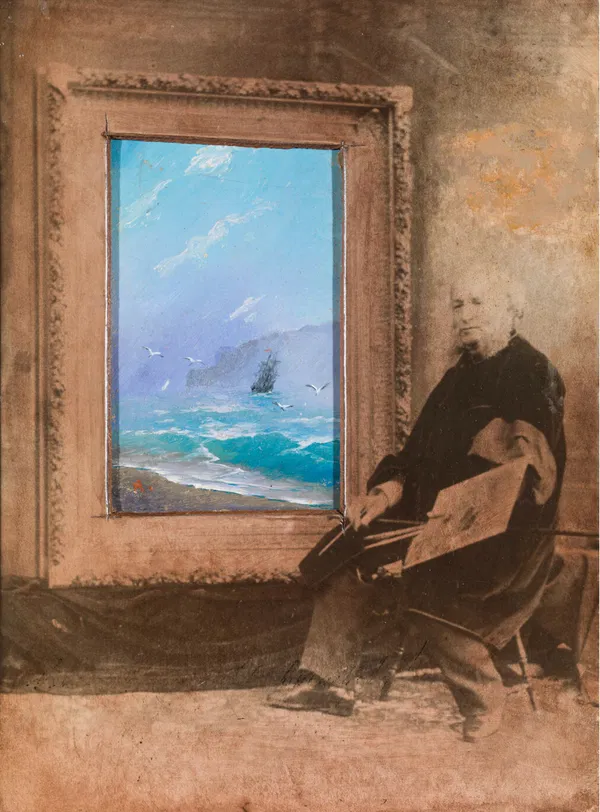

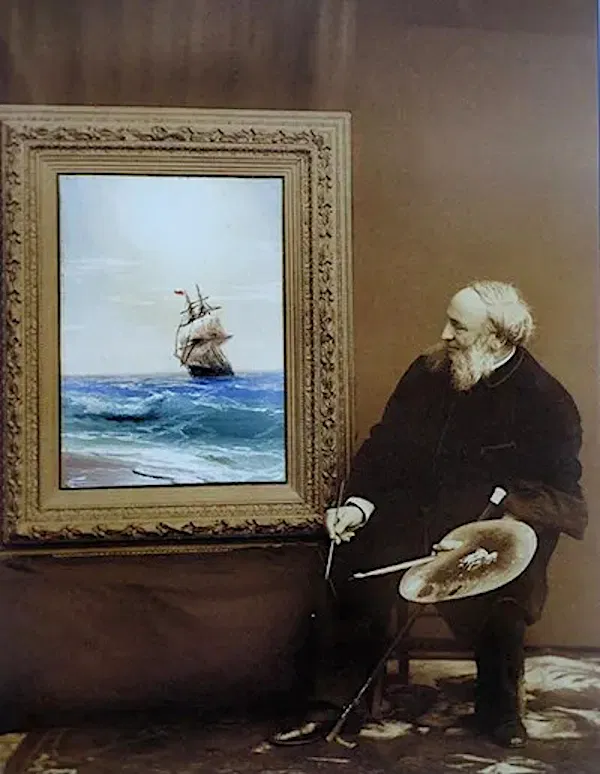

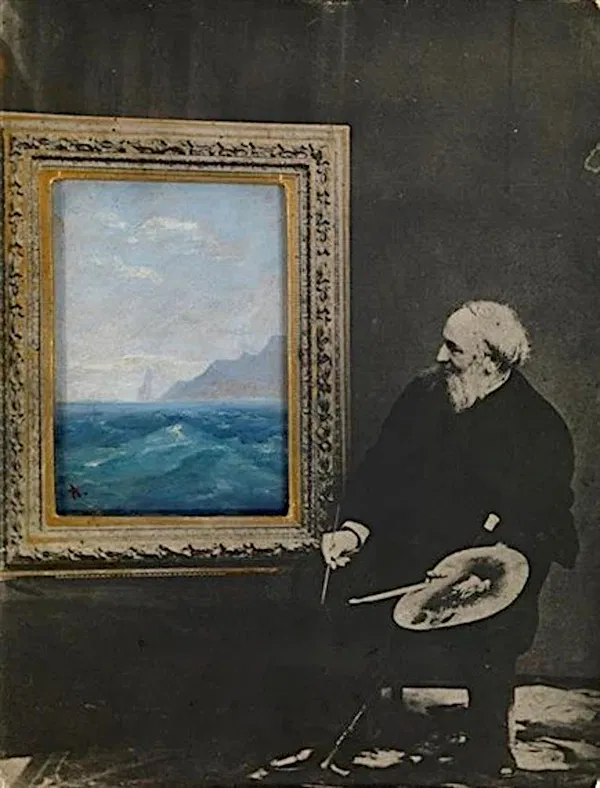

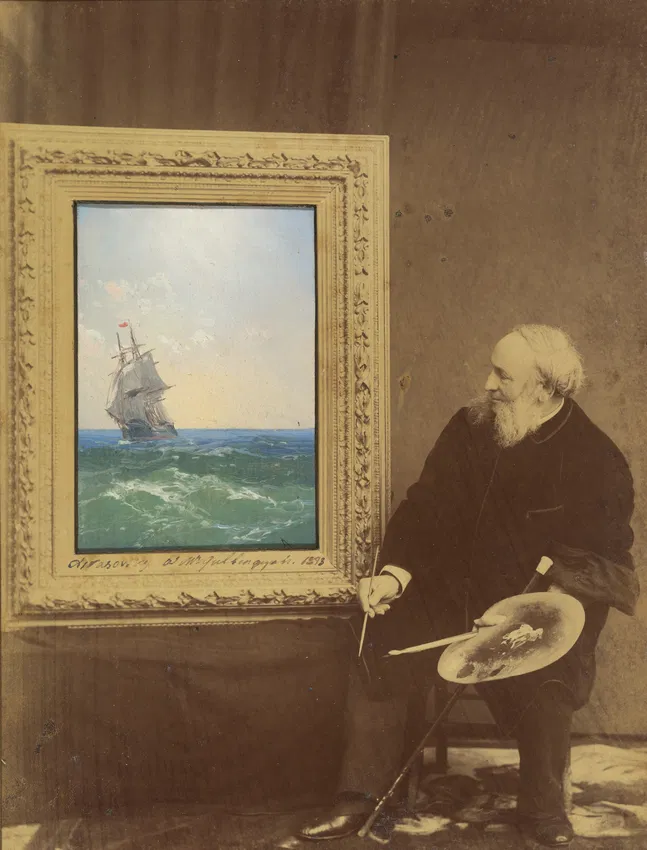

If you were lucky enough to be invited to Ivan Aivazovsky’s 70th birthday party in 1887, you didn’t leave with just a slice of cake and a handshake, you walked away with a painting. And not just any painting. Each of the 150 guests received an original, hand-painted seascape, created by the great marine artist himself, delicately painted on a tiny photographic portrait of Aivazovsky at work, brush in hand.

For a man known for canvases that could swallow a wall whole, this was a striking departure. But it was also pure Aivazovsky: a mix of generosity, showmanship, and artistry that made him one of the most fascinating painters of the 19th century.

A Storm on Canvas

Born in 1817 in the Crimean port of Feodosia to Armenian parents, Ivan Konstantinovich Aivazovsky grew up surrounded by the sea. The sound of waves, the changing light over the water, and the bustle of ships in the harbour shaped both his childhood and his creative spirit. He once said,

“The movement of the sea and the glare of the sun are things that mesmerise me.”

By his early twenties, he was a sensation in the Russian Empire’s art scene. His immense oil paintings of turbulent seas, glowing with moonlight or fire-red sunsets, seemed to capture something more profound than realism. They were emotional, romantic, and almost cinematic in scale.

Take his 1850 masterpiece The Ninth Wave: a colossal painting measuring nearly 11 feet across, showing survivors of a shipwreck clinging to debris as a blazing dawn breaks over monstrous waves. The light, a hallmark of Aivazovsky’s work, is almost supernatural, bathing the sea in a red-gold hue that suggests both destruction and hope.

Critics at the time compared him to Turner for his treatment of atmosphere and to Byron for his passion. But Aivazovsky didn’t just paint the sea, he celebrated it. And in doing so, he became the Russian Empire’s most famous marine painter, his name revered from St. Petersburg to Constantinople.

The 1887 Birthday Gift: A Thousandth the Size, Twice the Charm

By 1887, Aivazovsky was a national treasure. He had painted for tsars, built his own gallery in Feodosia, and received countless honours. But to mark his 70th birthday, he decided to do something completely different, something playful and personal.

At a grand dinner attended by 150 guests, Aivazovsky presented each person with a gift: a unique miniature seascape painted directly onto a photograph of himself. Each photo shows him at an easel, poised mid-brushstroke. In one variation, he’s looking at the canvas; in another, he’s looking directly at the viewer.

The paintings themselves are astonishingly small, just 10.6 by 7.3 centimetres (around 4 by 3 inches), nearly a thousand times smaller than The Ninth Wave. Yet, within that tiny space, Aivazovsky managed to capture the same drama of light and movement that defined his full-sized canvases: waves crashing, skies glowing, sails billowing in the distance.

Some of these little treasures were signed and dated, while others appear to have been made later, suggesting that he continued giving them as gifts beyond his birthday. In a way, they were the 19th-century equivalent of limited-edition artist prints, except each was unique and hand-painted by the master himself.

A Prolific Genius and His Critics

Aivazovsky’s productivity was legendary. By the time of his death in 1900, he had produced around 6,000 paintings, an astonishing number for any artist. His brush seemed tireless, his imagination endless.

But not everyone was impressed by his speed. The influential Russian art critic Vladimir Stasov didn’t mince words:

“One who takes two hours to finish a painting should keep this unfortunate secret to himself! One should not go disclosing things like this, especially in front of young students! They should not be taught such carelessness and machine-like habits.”

To Stasov, Aivazovsky’s rapid execution risked turning art into routine, robbing it of depth and reflection. Yet others saw his swiftness as a kind of genius, an instinctive mastery that allowed him to capture the sea’s fleeting moods before they vanished.

Indeed, Aivazovsky often painted from memory, not direct observation. He claimed to remember the sea “in all its moods” and could conjure up storms or sunsets with almost photographic accuracy. His brushstrokes were fluid, his confidence absolute.

In one story, he was reportedly challenged by students to paint a storm without any reference material. He accepted and within hours produced a vast, swirling seascape that left them speechless.

Fame, Self-Promotion, and Gilded Furniture

By the late 19th century, Aivazovsky wasn’t just famous, he was fabulously wealthy. He built a lavish mansion in Feodosia complete with marble halls, gilded furniture, and his own private art gallery, which he opened to the public in 1880.

Visitors were stunned. The writer Alexander Vladimirovich, who visited in 1890, left a less-than-flattering account:

“If you did not know that in front of you was the creator of The Ninth Wave, you would probably take him for a painter who had sunk into smug self-contemplation of his own bureaucratic position, proud of finally having worked his way up to a certain salary that allowed him to acquire gilded furniture and hang a full-length portrait of himself in full regalia in the living room to impress visitors.”

It’s easy to see how his extravagant tastes and those self-portrait gifts might have rubbed some people the wrong way. Aivazovsky loved recognition. He often signed his name in grand, sweeping script, and he wasn’t shy about reminding others of his achievements. But perhaps that confidence was part of what made him such a force. He understood the importance of image, of branding, long before the term existed.

In the world of 19th-century art, where most painters relied on royal patronage or the mercy of critics, Aivazovsky carved out something closer to modern celebrity.

The Sea as Memory and Metaphor

Despite his critics, Aivazovsky’s work endured because of its emotional power. His seas are not just depictions of water and sky; they’re metaphors for life itself, unpredictable, luminous, and vast.

He once said, “The sky and the sea are boundless, and in them lies the mystery of the soul.”

Many of his later paintings, particularly those made after the loss of his wife, showcase a more melancholy tone. The waves are softer, the skies paler. Yet even in sadness, there’s light. His ability to transform grief into beauty is perhaps what makes his art timeless.

His miniature seascapes, painted on his own photograph, can be read as a symbolic gesture, the artist placing himself quite literally inside his work, a man and his sea merged into one.

A Pioneer of Mixed Media

What makes those tiny birthday paintings even more remarkable is their innovation. By embedding painted seascapes into photographs, Aivazovsky effectively became an early pioneer of mixed media, decades before avant-garde artists would experiment with collage and photomontage.

Artists like Hannah Höch and John Heartfield in the 1920s, or Robert Rauschenberg in the 1950s, are often credited with blurring the boundaries between painting and photography. But Aivazovsky did it first, albeit in a more romantic and less subversive way.

His work sits at an intriguing crossroads: part fine art, part self-portrait, part souvenir. It shows that even at 70, he was still willing to experiment, still eager to surprise his audience.

A Lasting Legacy

Ivan Aivazovsky died in 1900, reportedly at his easel, brush still in hand. His final painting, The Explosion of a Turkish Ship, was left unfinished.

Today, his legacy endures not just in museums like the Hermitage and the Tretyakov Gallery, but also in Feodosia, where his home and studio have been preserved as the Aivazovsky National Art Gallery. His seascapes continue to command staggering prices at auction, some selling for millions.

But perhaps his most charming legacy lies in those small photographic gifts. These tiny hybrids of painting and portraiture tell us so much about who Aivazovsky was: confident, sentimental, endlessly inventive, and perhaps just a little vain.

As art historian Gianni Caffiero once remarked, “Aivazovsky did not simply paint the sea, he was the sea. His moods, his brilliance, his storms, all of them lived through him.”

So whether you stand before the monumental sweep of The Ninth Wave or hold one of his palm-sized miniatures, you’re witnessing the same boundless imagination, a man forever chasing the light across the horizon.

Sources

State Russian Museum archives

Gianni Caffiero & Ivan Samarine, Ivan Aivazovsky: Catalogue Raisonné of Paintings (2000)

“Ivan Aivazovsky and the Sea,” Tretyakov Gallery Magazine, Issue 3, 2017

Vladimir Stasov, Selected Critical Essays on Russian Art (1894)

Alexander Vladimirovich, travel notes (1890), Feodosia Archives

Hermitage Museum online collection: www.hermitagemuseum.org

Aivazovsky National Art Gallery, Feodosia: www.feogallery.ru

Comments