The House Of Guinness: More Myths Than Malt

- Daniel Holland

- Sep 14, 2025

- 11 min read

If there is a business with more books written about it than Guinness, it is hard to find. This is effectively a one product company, yet it has inspired tens of millions of words. There are at least eighteen substantial books covering the brewery, the people, the product, and the advertising, four of them by people actually called Guinness. On top of those, there are the pocket handbooks the company gave to visitors at St James’s Gate between 1928 and 1955. And yet, despite the shelves of Guinnessiana, myths and misunderstandings continue to swirl around the brand like the creamy head of a pint.

For all the words written, a surprising amount of Guinness folklore still gets repeated as if it were gospel. The early years in particular are a tangle of half truths and wishful thinking. There are still confident claims about Arthur Guinness’s exact date of birth. There is still the story that the secret of Guinness was a uniquely magical family yeast that Arthur carried with him like a relic when he moved to Dublin. The brewery’s own records contradict that. As early as 1810 to 1812, and very likely before, St James’s Gate was borrowing yeast from seven different breweries. Not quite the image of a single sacred strain passed down through the ages.

What makes Guinness so fascinating is that the myths sit alongside real stories that are far stranger than most people realise. There was a scandal in the late 1830s that nearly blew up the partnership. There was the managing director who suffered a sudden attack of insanity and had to be carried out of the brewery in a straitjacket in 1895. And there were later generations who lived gilded, extravagant lives in the twentieth century, rubbing shoulders with aristocracy, artists, musicians, and the Beatles.

Five Guinness myths that refuse to quit

Arthur Guinness was born in 1725 on 24 September in Celbridge.

The Dictionary of Irish Biography gives 12 March 1725. His gravestone in Oughterard, however, records that he died on 23 January 1803 “aged 78.” That means he must have been born between 24 January 1724 and 23 January 1725. His exact birthday is unknown.

Arthur’s father brewed for Archbishop Price and taught his son the craft.

Richard Guinness was land steward to the future Archbishop of Cashel, but there is no evidence that he brewed. Large houses often had their own brewing operation, but that work would usually be done by servants rather than the steward. The idea of Arthur learning his trade from his father on the estate has no proof.

The Archbishop’s bequest of £100 funded the first brewery.

Arthur and Richard each received £100 when Archbishop Price died in 1752, but Arthur did not buy the Leixlip brewery until 1755. The bulk of the funds almost certainly came from Richard’s savings and his time running the White Hart inn in Celbridge.

Guinness was always brewed with roasted barley.

Unmalted barley was illegal when Arthur started brewing. Roasted barley only entered Guinness recipes around 1929–30. The dark colour of early porter came from dark malts, not roasted barley.

The famous nine thousand year lease showed Arthur’s supreme confidence.

It makes a good story, but the lease was almost certainly a legal workaround to avoid transferring the freehold outright. It was more property fix than prophecy.

The scandal that almost ended Guinness

By 1839, Arthur Guinness II, son of the founder, was in his seventies and easing out of daily control. His two sons, Benjamin Lee and Arthur Lee, had been raised to run the brewery. On paper it looked secure. In practice it was anything but.

Arthur Lee lived in an apartment inside the St James’s Gate complex. He collected art, wrote poetry, sealed letters with a Greek god, and filled his rooms with Chinese furniture, knick-knacks, statues and a fountain that played into a willow tree. In the spring of 1839 the brewery hired an 18-year-old clerk, Dionysius Boursiquot. Slim, lively and handsome, he later changed his name to Dion Boucicault and became one of Ireland’s most famous playwrights. Arthur Lee became besotted.

The Guinness archives suggest Arthur Lee began issuing notes on the partnership without his father or brother’s knowledge. The inference is that he was giving money to Boucicault, or was being blackmailed. Whatever the truth, the sums were serious. In a surviving letter to his father, Arthur Lee confessed with anguish:

“My dear Father, I well know it is impossible to justify to you my conduct … Believe me above all that for worlds I would not hurt your mind if I could avoid it. Your feelings are most sacred to me.”

Boucicault was soon paid off. By 1840 he was in London with enough money to buy a horse and carriage and entertain friends. Arthur Lee left the partnership with £12,000 to buy a home at Stillorgan Park, where he lived in flamboyant style, hosting dukes and earls while a blind harper played melodies in the garden. At one point, the scandal threatened to dissolve the partnership entirely – which would have meant the end of Guinness. Only the determination of Benjamin Lee and others kept the brewery alive.

The day the managing director lost his mind

By the 1880s, Edward Guinness, Arthur Lee’s nephew, was in charge. He was ambitious but enjoyed the good life, delegating the hard graft to his wife’s brother Claude. Claude was brilliant, Oxford-educated, and became managing director. Edward focused on shooting grouse in Scotland and yachting with the Prince of Wales.

In 1890 the brewery floated as a public company. Edward was ennobled as Lord Iveagh and bought Elveden Hall in Suffolk. But in 1895, disaster struck. Claude suffered a sudden breakdown at St James’s Gate and had to be carried out in a straitjacket. Rumours suggested syphilis, though evidence is lacking. Within weeks he was dead at 43. The shock tore through the brewery, and Edward was forced back into direct control for decades. Some later argued that Guinness’s sluggish response to post–First World War challenges stemmed from this moment, Claude’s death cut short a more modernising path.

The Guinnesses in the 20th century

By 1900, Guinness was the largest brewery in the world, and the family were among Britain’s richest dynasties. Their wealth, homes, and social lives made them prominent in both Ireland and England.

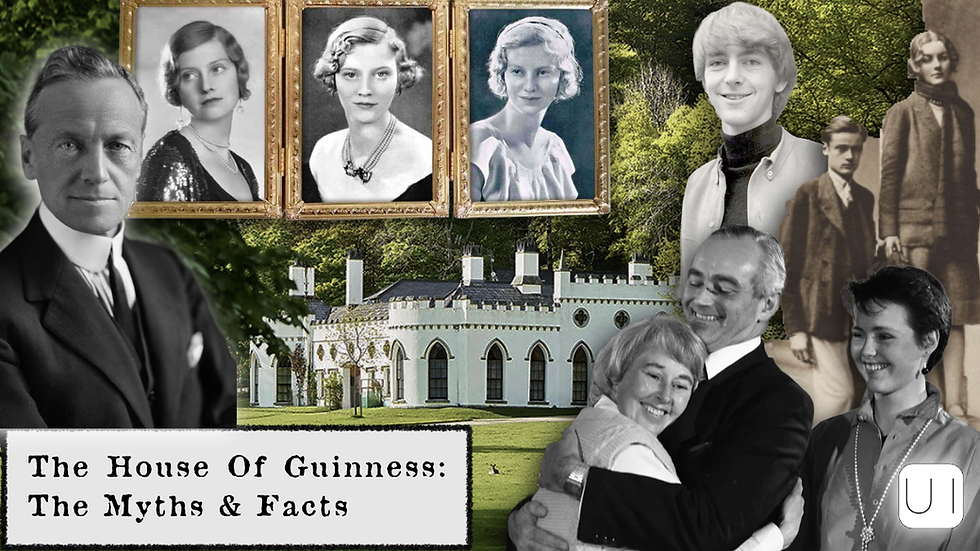

The “Golden Guinnesses”

In the 1920s and 1930s, three glamorous sisters – Aileen, Maureen, and Oonagh – became known as the “Golden Guinnesses.”

Aileen Guinness married Brinsley Plunket and became a celebrated London hostess.

Maureen Guinness married Basil Blackwood and moved in Anglo-Irish political and social circles.

Oonagh Guinness, perhaps the most dazzling, married first Philip Kindersley and later Dominick Browne, 4th Baron Oranmore and Browne. She presided over Luggala, her Wicklow estate, which became a haven for writers, artists, and musicians.

The sisters were painted by Cecil Beaton, photographed for society magazines, and written about endlessly. They defined interwar glamour and reinforced the Guinness family’s place at the centre of cultural life.

Tara Browne and Swinging London

In the 1960s, the Guinness connection shifted from society salons to rock and roll. Tara Browne, Oonagh’s son, was born in 1945 and grew up amid privilege, but embraced the bohemian spirit of Chelsea. With striking looks, charisma, and sharp style, he became a central figure in Swinging London.

Tara was friends with Brian Jones of the Rolling Stones, Paul McCartney, and John Lennon. He moved between Chelsea parties, Carnaby Street boutiques, and London clubs. He was known for his taste in fashion, his quick wit, and his reckless driving in his Lotus Elan.

On 18 December 1966, Tara ran a red light in South Kensington and was killed in a crash. He was only twenty one. His death stunned London’s artistic elite. John Lennon used it as inspiration for the opening lines of A Day in the Life:

“He blew his mind out in a car. He did not notice that the lights had changed.”

Paul McCartney later explained that while Lennon’s words referred directly to Tara, the song became a wider meditation on news and mortality. Tara’s brief life was thus set forever inside one of the Beatles’ most enduring works.

A darker modern thread: Lord Moyne and the so called curse

The twentieth century also brought events that shaped a persistent narrative of misfortune.

Lord Moyne

Born in 1880, Walter Edward Guinness, later Lord Moyne, was the great great grandson of Arthur Guinness, a friend of Winston Churchill, and the British minister resident in the Middle East. As historian Bernard Wasserstein relates, on 6 November 1944, Moyne arrived at his Cairo residence with his chauffeur, secretary, and ADC. Two young men stood near the entrance. They attacked the party, shot the chauffeur in the chest, and fired three shots at Moyne through the car window. The driver died at once. Moyne was taken to hospital, operated upon, and died later that day. The assassins, caught while fleeing, were identified as members of Lohamei Herut Yisrael, also known as Lehi, the Fighters for the Freedom of Israel. The killing resonated across British politics and the region and is often cited as the first major modern tragedy to fuel later talk of a curse upon the family.

Bryan and Diana Guinness

Years earlier, there had been scandal of a different kind. Bryan Guinness, son of Lord Moyne, gentle and eager to please, married Diana Mitford in 1929. They were bright ornaments of the Bright Young People, the set of aristocratic London socialites whose parties inspired Evelyn Waugh. His novel Vile Bodies was dedicated to the pair. It fell apart in 1932 when Diana met Sir Oswald Mosley, who became leader of the British Union of Fascists, and began an affair. She left Bryan and their two children, and married Mosley in Berlin in 1936 with Adolf Hitler among the guests. During the war Diana and Mosley were imprisoned without trial. The glamour of the early years curdled into notoriety.

Lady Henrietta Guinness

Tara Browne’s half sister, Lady Henrietta, lived a cosmopolitan life and mixed with artists and writers. She survived a near fatal car crash on the French Riviera when her boyfriend, the beatnik Michael Beeby, crashed his flame red Aston Martin. She later lived in Spoleto with Luigi Marinori and had a daughter. Treated for depression, she died in 1978 at thirty five after jumping from the Ponte delle Torri. She once said, “If I had been poor I would have been happy.”

1978 and a cluster of losses

That year proved grim for the wider family. Diplomat John Guinness survived a car crash in which his four year old son Peter died. A seventeen year old member of the family died of a suspected drug overdose. Major Dennys Guinness was found dead in a Hampshire cottage after recent questioning over possible firearms offences. The sense of a run of terrible luck grew.

Maureen Guinness and a troubled next generation

Maureen, one of the Golden Guinness sisters, was famous for social ambition and sharpness. Her daughters often felt neglected and acted out. Lady Caroline Blackwood, her eldest, became a celebrated muse and writer. Her life was turbulent. Her daughter, Natalya Citkowitz, died in 1978 at eighteen after hitting her head and drowning while using heroin. The Independent later wrote up the pattern of addiction and instability that haunted this branch of the family.

The kidnapping of Jennifer Guinness

In April 1986, banker John Guinness, chairman of Guinness and Mahon and a sixth cousin of the brewery chairman, returned home in Dublin to find his wife and daughter tied up. The attackers abducted his wife, Jennifer, and demanded a ransom of 2.6 million dollars. She was rescued eight days later without payment after a major police operation. The shock did not end there. Two years later, in 1988, John died after a fall of five hundred feet while climbing Snowdon with his family.

The death of Olivia Channon

Also in 1986, Oxford’s Christ Church College saw the death of twenty two year old Olivia Channon, daughter of Trade and Industry Secretary Paul Channon and an heiress to the Guinness fortune. She was found dead in a student room after taking heroin and alcohol. Three people were charged for supplying heroin, among them her friend Rosie Johnston and her third cousin Sebastian Guinness, who received a short prison term for possession. The case became a stark symbol of drug use among the wealthy.

The Bismarck shadow

The room belonged to Count Gottfried von Bismarck. He was fined for possession and told the incident would shadow him. He later fell into a destructive spiral. After a series of wild parties, he died in 2007 at forty four with extreme levels of cocaine in his system. Though not a Guinness, the sad arc of his life became entangled with the memory of Olivia’s death.

Sheelin Rose Nugent

In 1998, Sheelin Rose Nugent, niece of the Earl of Iveagh, died in a freak accident while driving a horse drawn Romany caravan near her mother’s home on her mother’s birthday. Something spooked the horse and the wagon overturned. There were no other vehicles and no clear cause. She was an experienced horsewoman. The mystery only deepened the family’s sense of hard luck.

Honor Uloth

In 2020, nineteen year old Honor Uloth, granddaughter of Benjamin Guinness the third Earl of Iveagh, died after an accident at a family gathering in Sussex. After time in a hot tub, she took a swim alone. She was later found at the bottom of the pool with a broken shoulder and severe brain injuries. It is thought she struck her head as she entered the water. She died six days later. The family spoke of her having spent the day among people and pastimes she loved.

These events do not prove a curse. They do show how a famous name becomes a lens through which chance, risk, wealth, addiction, and pressure are read. The Guinness story contains both glamour and grief, sometimes in the same generation.

A last word and one good thirst

Guinness is a rare thing. A single drink that became a global symbol. A family business that grew into a corporate empire while still feeling oddly personal. The truth is tangled. Some of the best known stories are wrong. Some of the least known are so human that the harp strings almost sound as the page turns.

There is still plenty left to discover. The archives will always keep a few secrets. New writers will keep adding to the shelf. In the meantime, next time someone swears that Arthur signed a nine thousand year lease because he knew he would change the world, smile, take a sip and remember that good brewing and good storytelling both rely on careful work, not magic.

Ten books on Guinness that are worth the pour

The Guinnesses by Joe Joyce (2009) – The best general overview of the family and the brewery, lively and thorough.

Arthur’s Round by Patrick Guinness (2008) – Excellent on the early years and the roots of Arthur Guinness I.

Guinness’s Brewery in the Irish Economy 1759–1876 by Patrick Lynch and John Vaizey (1960) – A pioneering business history.

Guinness 1886–1939: From Incorporation to the Second World War by S. R. Dennison and Oliver MacDonagh (1998) – Detailed and scholarly.

A Bottle of Guinness Please by David Hughes (2008) – Packed with detail on bottling, exporting, and brewing practices.

The Book of Guinness Advertising by Jim Davies (1998) – Lavishly illustrated, covering Guinness’s long run of iconic adverts.

The Guinness Book of Guinness by Edward Guinness (1988) – A massive collection of anecdotes about the Park Royal brewery.

Requiem for a Family Business by Jonathan Guinness (1997) – An insider’s account of the decline of family control.

The Guinness Spirit by Michele Guinness (1998) – A broad look at the family beyond brewing, including missionaries and bankers.

Guinness Times: My Days in the World’s Most Famous Brewery by Al Byrne (1999) – A memoir from the inside, warm and insightful.

Sources

Joe Joyce, The Guinnesses (Gill & Macmillan, 2009)

Patrick Guinness, Arthur’s Round (Liberties Press, 2008)

Patrick Lynch & John Vaizey, Guinness’s Brewery in the Irish Economy 1759–1876 (Cambridge University Press, 1960)

S. R. Dennison & Oliver MacDonagh, Guinness 1886–1939: From Incorporation to the Second World War (Cork University Press, 1998)

David Hughes, A Bottle of Guinness Please (Phimboy, 2008)

Jim Davies, The Book of Guinness Advertising (Hamlyn, 1998)

Edward Guinness, The Guinness Book of Guinness (Secker & Warburg, 1988)

Jonathan Guinness, Requiem for a Family Business (Palgrave Macmillan, 1997)

Michele Guinness, The Guinness Spirit (Hodder & Stoughton, 1998)

Al Byrne, Guinness Times: My Days in the World’s Most Famous Brewery (Gill & Macmillan, 1999)

Cecil Beaton portraits of the Guinness Sisters, National Portrait Gallery

John Lennon & Paul McCartney, interviews on A Day in the Life (Beatles Anthology, 1995)

“The Death of Tara Browne,” The Guardian, December 1966

“The Golden Guinness Girls,” Irish Times, September 2020

Comments