Training for the Moon: How Nine of the Twelve Apollo Astronauts Rehearsed Their Missions in Iceland

- Oct 27, 2025

- 9 min read

If you travelled through the Icelandic Highlands in the mid-1960s, you might have stumbled upon a curious sight: men in silver NASA jackets trudging across a volcanic wasteland, stopping to hammer at rocks, crouching over maps, and scribbling in notebooks while local guides looked on bemused. These weren’t lost tourists. They were astronauts, future moonwalkers, preparing for humanity’s greatest leap.

Between 1965 and 1967, Iceland became one of NASA’s most unlikely yet most important training grounds. The Apollo astronauts came not to test rockets, but to study rocks. And among those who wandered the lava fields of Askja and Mývatn were nine of the twelve men who would go on to set foot on the Moon.

It’s an extraordinary, lesser-known chapter of the Space Age, a story where the alien landscapes of Iceland became a stand-in for the lunar surface, and where future moonwalkers learned how to think, move, and collect like geologists on another world.

Why Iceland Looked Like the Moon

When NASA prepared to send humans to the Moon, engineers weren’t the only ones in demand. Geologists were too. Once astronauts reached the lunar surface, they’d have to act as field scientists—selecting samples, describing terrain, and making split-second geological judgements that could inform decades of research back on Earth.

But there was a problem: how do you train for the geology of a place no one has ever been?

NASA’s answer was to find “Earth analogues”, landscapes on our planet that looked and behaved like those they might encounter on the Moon. The search led them to deserts, volcanic craters, and remote mountains. Yet few places on Earth could match Iceland.

Situated at the meeting point of the North American and Eurasian tectonic plates, Iceland is a geologist’s dream—or a traveller’s moonscape. Black lava flows stretch for miles. Steam hisses from vents. Glacial rivers carve deep valleys through volcanic ash. The result is a bare, surreal land that one astronaut later described as “utterly unearthly”.

According to NASA geologist Dr. Gene Shoemaker, who led much of the Apollo field training, Iceland “displayed volcanic geology with almost no vegetation cover—an ideal terrain to simulate the Moon.” The basaltic rocks found there were similar in composition to those scientists expected on the lunar surface.

It wasn’t just about resemblance. Iceland’s isolation, unpredictable weather, and ruggedness also gave the astronauts a taste of what it might be like to operate in an environment where communication, navigation, and comfort couldn’t be taken for granted.

I spent around ten days exploring the volcanically active regions of Iceland, a place so stark and barren I felt as if I were already on the moon. We were there in the summertime, and it seemed like the sun never set. You could be out at 3 a.m. and see people strolling the city streets, the stores still open”-Al Worden, Apollo 15 Astronaut

The 1965 and 1967 Expeditions

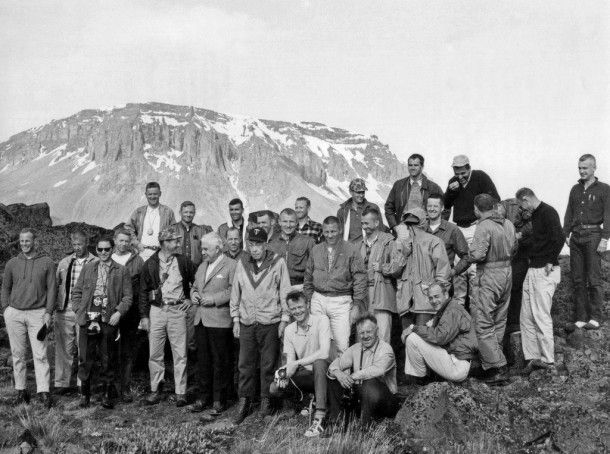

NASA’s first official geological training expedition to Iceland took place in July 1965, led by USGS geologists and Icelandic scientists from the University of Iceland. The group included ten astronauts: Bill Anders, Alan Bean, Eugene Cernan, Roger Chaffee, Walter Cunningham, Donn Eisele, Rusty Schweickart, David Scott, and Clifton Williams.

They spent a week in the central highlands, examining the lava fields of the Reykjanes Peninsula and the volcanic formations near Lake Mývatn. They studied volcanic cones, basaltic lava flows, and fissures, learning to describe and sample them methodically—skills that would later prove critical on the lunar surface.

Two years later, in July 1967, NASA returned for a second field trip. This one was larger and even more ambitious, taking astronauts deep into Iceland’s remote interior, particularly the Askja caldera in the Dyngjufjöll mountains.

Among those present were Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin, Charles Duke, Edgar Mitchell, Harrison Schmitt, and David Scott—all future moonwalkers. For many, the Askja caldera was the closest they would ever get to the Moon before actually going there.

The group camped in rugged conditions, living in tents beside the milky blue Víti crater lake. Each day they trekked across lava fields and ash plains, taking field notes and practising sample collection. “It was an incredibly barren place,” remembered Apollo 15 astronaut David Scott. “No trees, no grass, no birds. Just rock and silence. It was perfect.”

Nine Moonwalkers in Iceland

Of the twelve men who would ultimately walk on the Moon between 1969 and 1972, nine trained in Iceland. They were:

Neil Armstrong (Apollo 11) – The first man on the Moon trained in Iceland in 1967, studying volcanic geology around Askja.

Buzz Aldrin (Apollo 11) – Armstrong’s crewmate also took part in the 1967 training sessions, learning field mapping and rock sampling techniques.

Alan Bean (Apollo 12) – A participant in the 1965 field trip, Bean later credited his geological training in Iceland with helping him recognise important features on the lunar surface.

Eugene Cernan (Apollo 17) – The last man to walk on the Moon, Cernan attended the 1965 session, years before commanding Apollo 17.

David Scott (Apollo 15) – A member of the 1965 expedition, Scott’s time in Iceland proved invaluable for the Moon’s first extended geological exploration.

Charles Duke (Apollo 16) – Duke, who also served as CAPCOM during Apollo 11, joined the 1967 field team.

Edgar Mitchell (Apollo 14) – Participated in 1967, where he learned to identify volcanic and impact features.

Harrison Schmitt (Apollo 17) – A trained geologist himself, Schmitt joined the 1967 Iceland fieldwork as both student and peer to NASA’s instructors.

Pete Conrad (Apollo 12) – Though not always listed, records suggest Conrad trained with NASA’s geology teams in Icelandic-like field conditions prior to his mission.

The other three moonwalkers—Alan Shepard, John Young, and James Irwin—trained elsewhere, particularly in the volcanic landscapes of Hawaii, Arizona, and Nevada.

We went to Hawaii, to Iceland, great places to focus on volcanic rocks. The assumption was that on the Moon we would encounter tectonic formations principally, or remnants of volcanic and tectonic lava flows, that sort of thing. I was very tempted to sneak a piece of limestone up there with us on Apollo 11 and bring it back as a sample.”– Neil Armstrong, Apollo 11 Astronaut

Learning to Think Like Geologists

In Iceland, the astronauts weren’t just sightseeing. Their schedule was rigorous, combining field instruction with long days of hiking and observation.

NASA instructors taught them how to “read the rocks” and recognise geological formations. The astronauts learned to distinguish between different lava types, spot signs of past eruptions, and record detailed descriptions that would later help scientists interpret the Moon’s history.

One Icelandic geologist, Sigurður Þórarinsson, played a major role in the 1967 training. His knowledge of the region’s volcanic systems impressed NASA. “He could look at a landscape and tell you the story of every eruption,” recalled one astronaut. “We wanted to be able to do the same thing on the Moon.”

Field practice included:

Sample collection: Using hammers, chisels, and tongs, the astronauts learned how to extract small but representative samples without contaminating them—vital for lunar geology.

Documentation: They practised describing rock textures, layering, and colour variations, and taking photographs to record context.

Traverse planning: Since Moon missions involved time-limited surface walks, astronauts practised navigating terrain quickly but efficiently.

Team coordination: Each pair of astronauts trained to communicate clearly—one often acted as the observer while the other collected samples.

Harrison Schmitt later said that fieldwork in Iceland gave astronauts “a sense of how to move and think as field geologists, not just pilots.” That distinction mattered. On the Moon, there would be no second chances, every sample collected had to count.

Askja: The Closest Place on Earth to the Moon

The crown jewel of NASA’s Icelandic training sites was the Askja caldera, a vast volcanic depression formed by a massive eruption in the 19th century. Within it lay a smaller crater called Víti (“Hell”), filled with a vivid turquoise lake. Around it, the ground was littered with black volcanic glass and coarse ash—eerily similar to what lunar regolith would later prove to be.

It’s no exaggeration to say Askja became a proving ground for the Apollo program. The astronauts practised traversing slopes, collecting samples, and working as teams under the supervision of geologists.

A photograph taken there shows Neil Armstrong kneeling in the dust, hammer in hand, surrounded by lava fragments. His white helmet gleams in the weak northern light. Another image shows Buzz Aldrin crouched beside a fissure, peering into the earth like a scientist rather than a soldier of the Cold War.

The local Icelanders were fascinated. Some guides and scientists joined the excursions, while others watched from afar, not yet aware that the men before them would soon make history.

In later years, Icelanders would fondly recall how their remote island had hosted the most famous explorers of the 20th century. “We didn’t know at the time how big it was,” one resident from Mývatn later said. “They were polite, quiet men who looked at rocks all day. Then they went to the Moon.”

One of my most memorable trips was to the volcanically active and very remote region of central Askja, Iceland, in July 1967. Known for its volcanic craters called calderas, this region had a very rocky terrain with black volcanic sand, as well as a large lake and hot springs. It was a misty, surreal place unlike anything I’d ever seen in my travels. And because we were there during the summer it seemed like the sun never set.” -Edgar Mitchell, Apollo 14 Astronaut

From Lava to Lunar Soil

The practical value of this training became clear during the Apollo missions. When astronauts began describing and sampling lunar rocks, their Icelandic experience showed.

David Scott, who commanded Apollo 15, the first mission devoted heavily to lunar geology, was praised for the precision and detail of his observations. “He knew how to describe a rock in a way that made sense to scientists back on Earth,” said one NASA geologist. “That came straight from the field training.”

Likewise, Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin’s efficiency on Apollo 11, collecting 21.5 kilograms of samples in just over two hours, was no accident. They had practised similar sampling techniques in Iceland, learning to work fast and think systematically under time pressure.

Apollo 17’s Harrison Schmitt, the only professional geologist to walk on the Moon, later reflected that Iceland’s barren landscapes had been “as close as any place on Earth could get to the lunar experience.”

Even decades later, NASA scientists note that Iceland’s terrain helped shape their understanding of what to expect on the Moon. The parallels were uncanny: both surfaces were basaltic, heavily fractured, and largely shaped by volcanic processes.

The People Behind the Scenes

While the astronauts became household names, the scientists who trained them deserve equal recognition. Figures like Dr. Gene Shoemaker, Dr. Gordon Swann, and Iceland’s Sigurður Þórarinsson made the field trips a blend of science and exploration.

Shoemaker, one of the founders of planetary geology, insisted that astronauts become more than just test pilots. “The Moon isn’t just a destination,” he said. “It’s a field site.”

Icelandic collaborators provided not only logistical help but also geological expertise. They taught the Americans how to read volcanic layers and recognise lava tube formations. Some Icelandic students who assisted on the 1967 expedition went on to work in international geology themselves, inspired by the experience.

The Legacy Lives On

Fifty years after the Apollo missions, Iceland’s connection to space exploration hasn’t faded.

In 2015, the town of Húsavík unveiled the Astronaut Monument outside its Exploration Museum, commemorating the 32 Apollo-era astronauts who trained in Iceland. Their names—including Armstrong, Aldrin, Bean, Cernan, and Schmitt—are engraved on polished stone. It’s a simple, powerful reminder that the path to the Moon once passed through a windswept volcanic island in the North Atlantic.

In recent years, NASA has returned. The Artemis II crew—who will orbit the Moon in the coming years—completed geology training in Iceland, using many of the same locations the Apollo astronauts once did. The reasoning hasn’t changed: there is still no better analogue for lunar landscapes on Earth.

Harrison Schmitt summed it up best when asked about Iceland’s role in space history:

“It’s one of the few places where you can feel what it’s like to stand on another world without leaving this one.”

Iceland’s Gift to the Space Age

Iceland didn’t launch a rocket or build a spacecraft, yet it played an essential role in one of humanity’s greatest achievements. The lunar landings weren’t just triumphs of engineering—they were triumphs of training, observation, and curiosity.

When Neil Armstrong stepped onto the Moon in July 1969 and described its surface as “fine and powdery,” he was speaking with the precision of a man who had studied volcanic ash in Iceland. When Buzz Aldrin picked up a rock, he did it with the careful hands of a field geologist who had learned to value every sample.

The black deserts of Iceland prepared them for the grey deserts of the Moon. The lessons they learned there echo still, in every mission that seeks to understand other worlds by first understanding our own.

Sources

Exploration Museum, Húsavík – “Apollo Astronaut Training in Iceland”: https://www.explorationmuseum.com/astronaut-training

NASA History Office – Apollo Geology Training Reports: https://ntrs.nasa.gov/api/citations/20190026783/downloads/20190026783.pdf

“The Lunar and Other Extra-Terrestrial Landscapes of Iceland,” Hey Iceland Blog: https://www.heyiceland.is/blog/nanar/7292/the-lunar-and-other-extra-terrestrial-landscapes-of-iceland

Stuck in Iceland Magazine – “Astronaut Training in Iceland: Discover New Worlds”: https://www.stuckiniceland.com/astronaut-training-in-iceland-get-ready-to-discover-new-worlds

NASA Science – “Artemis II Crew Uses Iceland Terrain for Lunar Training”: https://science.nasa.gov/missions/artemis/nasas-artemis-ii-crew-uses-iceland-terrain-for-lunar-training

Atlas Obscura – “Apollo Astronaut Training Memorial, Húsavík”: https://www.atlasobscura.com/places/apollo-astronaut-training-memorial

Comments