Sorosis and the Birth of America’s Women-Only Clubs

- Cassy Morgan

- Sep 6, 2025

- 6 min read

In the late 19th century, when women in America dared to step into professional careers, they were often met with relentless barriers. Prejudice wasn’t just common, it was woven into the very fabric of society. Women were expected to remain silent in public life, their ambitions confined to the domestic sphere. But as the women’s suffrage movement gained momentum after 1848, cracks began to appear in those rigid structures.

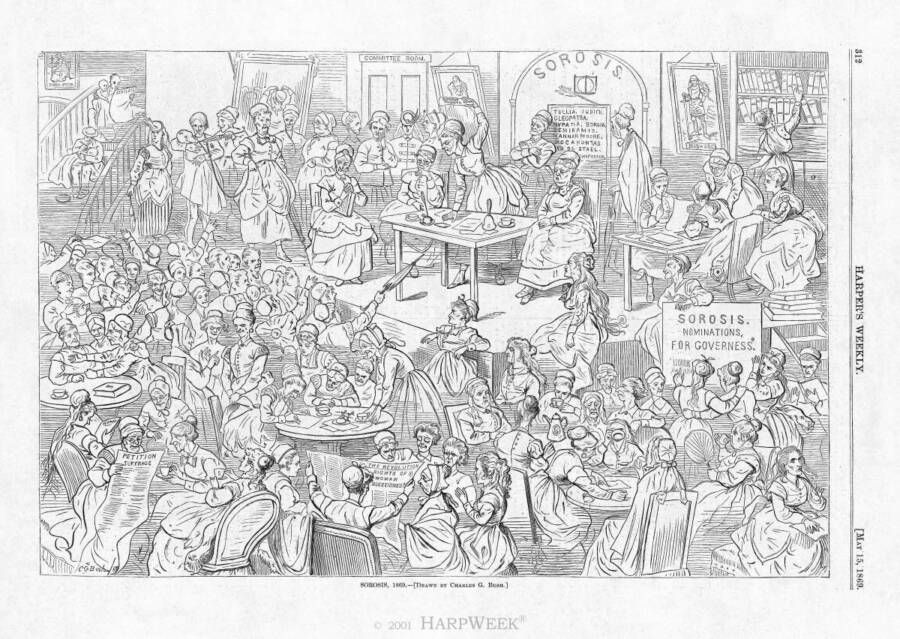

One of the most revolutionary responses came not from the ballot box, but from dining tables, lecture halls, and parlours, the creation of women-only clubs. These clubs gave women the freedom to meet, learn, and organise in ways society had long denied them. And at the heart of this movement stood the very first of them all: Sorosis.

Jane Cunningham Croly: A “Volcanic Force”

The story begins with Jane Cunningham Croly, a determined journalist working in New York City. In 1855, Croly joined the New York Tribune and became one of the first women in America to write a syndicated column. Her career was groundbreaking, but her assignments were restricted by her gender.

She wasn’t allowed to cover science, literature, art, or music, all considered too serious for a woman’s pen. Instead, she was pushed into the realm of gossip. Under the title Gossip with and for the Ladies, she earned just three dollars a week. With her pen name “Jennie June,” she later wrote Parlor and Sidewalk Gossip, bringing in five dollars per week.

Croly persevered, carving out respect in the male-dominated press world. By 1868, she had become a member of the New York Press Club. Yet when a banquet was announced to honour Charles Dickens, Croly and her female colleagues were denied tickets. The Club had decreed: no women allowed.

After much protest, the men relented, but only with an insulting condition. The women could attend if they sat hidden behind a curtain, invisible to both Dickens and the gentlemen present. Croly and her colleagues refused. As her brother once described, Croly was a “volcanic force,” and the rejection lit a fire in her.

“We Will Form a Club of Our Own”

Croly channelled her frustration into action.

“We will form a club of our own,” she declared. “We will give a banquet to ourselves, make all the speeches ourselves, and not invite a single man.”

She named the group Sorosis, from the Latin soror meaning “sister,” and also a botanical term for fruit formed from multiple flowers, such as a pineapple. The symbolism was perfect: many blooms coming together to form something stronger.

Croly was soon joined by children’s author Josephine Pollard, the popular columnist Fanny Fern, journalist Kate Field, magazine editor Ellen Louise Demorest, New York Ledger writer Anne Botta, and the poet sisters Alice and Phoebe Cary.

Membership was by invitation only. Prospective members had to pass inspection, swear a loyalty oath, and pay an initiation fee of five dollars, no small sum for the era.

Dining Out as Revolution

On April 20, 1868, Sorosis held its first meeting at Delmonico’s, an upscale restaurant in Lower Manhattan, the same place that had hosted Dickens.

Today, the idea of twelve women sitting down to lunch without husbands or escorts sounds utterly ordinary. But in the 19th century, it was radical. Respectable women simply didn’t dine out alone, and those who did were often assumed to be sex workers seeking clients.

By booking a table at Delmonico’s, the women of Sorosis were openly challenging social conventions. Within a year, membership swelled to 83, drawing in writers, historians, artists, scientists, and reformers. They were mostly middle-aged, middle- or upper-class white women — many of whom worked not out of passion, but necessity.

Fortunately, the Delmonico brothers, who ran the restaurant, welcomed the group. As Carin Sarafian, Delmonico’s Special Events Director, put it in 2018:

“It became their meeting place to exchange ideas around politics, history and the world. It was a place to be with other women.”

The meetings were far from frivolous. Croly had envisioned Sorosis as a place for the “collective elevation and advancement” of women — and that’s exactly what it became.

The Power of Sorosis

From the beginning, Sorosis was more than a social club. It was an incubator for ideas, a safe space for learning, and a training ground for leadership.

British activist Emily Faithfull visited in the 1880s and later wrote:

“In spite of a severe fire of hostile criticism and misrepresentation, [Sorosis] has evinced a sturdy vitality, and really demonstrated its right to exist by a large amount of beneficent work… Some people still ask, ‘What has Sorosis done?’ I believe it has been the stepping-stone to useful public careers, and the source of inspiration to many ladies.”

Sorosis welcomed not just professionals but also housewives and mothers. Its aim was to create civic-minded women who could bring change to their communities.

Its influence became so strong that men even tried to join. Their requests were firmly denied with this memorable statement:

“We willingly admit, of course, that the accident of your sex is on your part a misfortune and not a fault… Sorosis is too young for the society of gentlemen and must be allowed time to grow… But for years to come its reply to all male suitors must be, ‘Principles, not men.’”

A Toast to Women’s Kingdom

The tide was beginning to shift. Just a year after the Dickens debacle, members of Sorosis were invited back to Delmonico’s for a Press Club dinner. This time, the first toast, given by Fanny Fern and biographer James Parton was:

“Woman’s kingdom: if it is not kingdom come, it is kingdom coming.”

It was a small but significant victory, signalling that women’s voices could no longer be ignored.

From Clubs to Movements

By the 1890s, women’s clubs had multiplied across the country. Sorosis celebrated its 22nd anniversary by helping bring together 63 women’s groups to form the General Federation of Women’s Clubs (GFWC) in 1890.

Jane Cunningham Croly captured the spirit of the movement in her 1898 book The History of the Woman’s Club Movement in America:

“The woman has been the one isolated fact in the universe…. The outlook upon the world, the means of education, the opportunities for advancement, had all been denied her.”

The clubs changed that. They became engines of social reform, supporting suffrage campaigns, abolition, and later the war effort in World War I. Women who might once have been isolated in their parlours were now engaged in civic work and political advocacy.

Exclusion and Progress

It’s important to acknowledge that women’s clubs were far from inclusive. Most remained predominantly white and middle-class, often excluding women of colour and working-class women. Not until the 1960s did more racially integrated organisations begin to flourish.

Even so, Black women created their own networks, such as the Women’s League in Rhode Island, shown in photographs from the early 1900s. These groups provided vital spaces for leadership, education, and activism within their own communities.

A Legacy Still Felt

The movement sparked by Sorosis left an indelible mark. Clubs created platforms for women to learn, network, and organise at a time when they were legally and socially marginalised. They paved the way for the suffrage victory in 1920 and continued to nurture civic engagement long after.

Today, women-only clubs still exist, though many face challenges around inclusivity and relevance. Yet they remain rooted in the same principle that fuelled Jane Cunningham Croly more than 150 years ago: the belief that women thrive when they gather together, support one another, and claim their own space in the world.

Sorosis may have started as a response to exclusion from a Dickens banquet, but it grew into something far greater, a revolution of sisterhood, civic engagement, and determination.

Sources

Croly, Jane Cunningham. The History of the Woman’s Club Movement in America. New York, 1898.

Gourley, Catherine. Society Sisters: Women’s Suffrage in America. Twenty-First Century Books, 2007.

Faithfull, Emily. Visits and Sketches at Home and Abroad. 1884.

Delmonico’s official history: https://www.delmonicos.com

General Federation of Women’s Clubs: https://www.gfwc.org

Comments