Johnny Coulon The Bantamweight Boxer Who Became the Unliftable Man

- Julian Beckett

- Sep 16, 2025

- 5 min read

Imagine standing in front of a wiry man barely five feet tall, weighing no more than a sack of flour, and being told you couldn’t lift him an inch off the floor. You’d laugh, flex your muscles, and try—only to find yourself red-faced, straining, and baffled as the little man calmly stared back at you, his feet planted firmly on the ground. That was Johnny Coulon’s party trick, and it made him one of the most curious figures to ever step out of the boxing ring and onto the vaudeville stage.

Johnny Coulon wasn’t just a gimmick, though. He was a world champion bantamweight boxer, a man who fought more than 90 professional bouts, trained champions long after his own career, and became a living legend in both sports and show business. Yet today, he’s best remembered for being “The Unliftable Man,” a performer whose mix of science, psychology, and theatre mystified strongmen, wrestlers, and even Muhammad Ali.

Early Life and Rise in Boxing

John Coulon was born on 12 February 1889 in Toronto, Canada, but his family moved to Chicago when he was still a boy. Chicago would become his lifelong home and the centre of his boxing story. Unlike many boxers who grew up in poverty or worked tough labouring jobs, Coulon’s path was unusual: his father Emile was a French-born ex-fighter himself and encouraged his son’s interest in the sport.

By his teens, Johnny was already competing in boxing matches around the Midwest. What he lacked in size, he made up for in speed, cleverness, and stamina. In the days before strict weight categories were properly regulated, bantamweights (fighters around 115 pounds) were often overlooked in favour of heavier divisions. But Coulon brought attention to the lighter class through his skill and charisma.

Between 1905 and 1910, Coulon built a reputation as a rising star. In 1910, at just 21 years old, he won the World Bantamweight Championship by defeating Jim Kendrick. For four years, he held the title and successfully defended it against a string of challengers. Sportswriters admired his tactical brain, fast footwork, and surprising punching power for a man of his frame. “He fought like a man twice his size,” one reporter noted.

From Champion to Showman

Coulon retired from professional boxing in 1920, ending a career that included more than 90 bouts. But his second act would prove even more unusual.

The 1920s were a golden age for vaudeville and sideshow acts. Crowds flocked to theatres not just for singers and comedians but also for “human curiosities” – strongmen bending iron bars, escape artists wriggling free of handcuffs, mentalists reading minds, and performers who blurred the line between science and the supernatural.

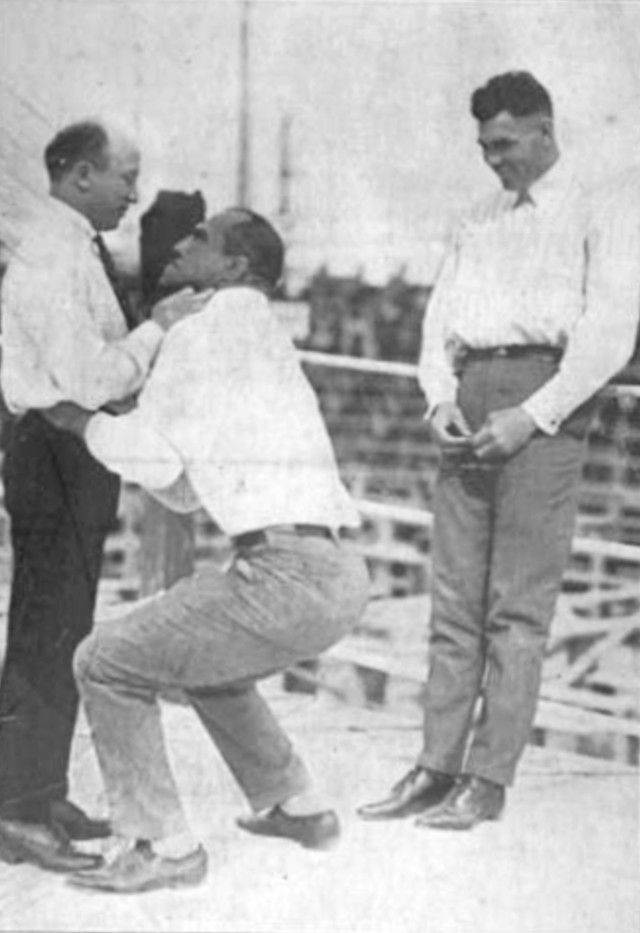

Coulon, with his small stature and wiry build, was perfectly placed to baffle audiences with his “unliftable” routine. The act was simple but devastatingly effective: he would invite a burly volunteer, often a wrestler, weightlifter, or even a famous heavyweight boxer, to try to lift him off the floor. At first, Coulon made it easy. He’d stiffen his body into a straight vertical line, sometimes even pushing down on the lifter’s wrists to help. The volunteer would raise him easily, drawing chuckles from the crowd.

But then Coulon would reset, apply his mysterious grip, and the scene would flip. The strongest of men, faces turning crimson, legs straining, would fail to budge him. The audience roared. How could a 110-pound man be heavier than a stone statue?

The Secret of the “Unliftable Man”

Part of Coulon’s genius lay in his showmanship. He played into the era’s fascination with Spiritualism and hidden powers. In the years after the First World War, people craved evidence of forces beyond the ordinary. Séances, mediums, and “human marvels” were wildly popular. In Paris, where Coulon toured in the early 1920s, newspapers speculated about “occult energy” or supernatural magnetism.

But in truth, the trick relied on a mix of physics, nerve pressure, and psychology.

Coulon would place his left hand lightly on the lifter’s wrist at the pulse point, a move that distracted the observer and suggested control over their blood flow. His real secret, though, was in his right hand. With his index finger pressed against the lifter’s neck, close to the vagus nerve, he applied a precise, uncomfortable pressure. At the same time, his right elbow locked against his own hip, creating a perfect fulcrum of leverage.

The harder the lifter strained, the more the pressure and counter-leverage worked against them. The sensation of nerve pain combined with the sheer mechanical disadvantage made the task nearly impossible. Even the strongest lifters, including future legends like Jack Johnson and Muhammad Ali, found themselves humiliated in front of laughing crowds.

Harry Houdini, the great escapologist and professional debunker of frauds, wasn’t fooled. “It’s hokum!” Houdini scoffed. “It’s the principle of the fulcrum and a matter of leverage. Coulon is in stable equilibrium and his subject isn’t.” Yet even Houdini admitted that the trick was brilliantly performed.

Paris in the 1920s – and the Coulon Craze

When Coulon took his act to Paris in 1920, the city was still reeling from the Great War. Death and destruction had left many people fascinated by the possibility of unseen powers, and Spiritualism was at its peak. Mediums claimed to contact the dead, and public appetite for the mysterious was insatiable.

Coulon arrived at just the right time. The French press reported on his act as if it were a scientific puzzle. Workers in Paris offices began experimenting with “Coulon lifts,” pressing and prodding their colleagues in futile attempts to replicate the trick. “For days, no work was done in Paris,” one paper joked, “because every small man was being conscripted into Coulon experiments.”

The cultural moment turned a boxing champion into an international sensation.

Later Life and Legacy

Eventually, the novelty wore off. By the 1930s, the vaudeville circuit was in decline, audiences moved on to cinema, and Coulon left the stage. But he remained a central figure in boxing.

Settling in Chicago, he opened a gym and trained generations of fighters. Among his protégés was Jackie Fields, who went on to become a world welterweight champion and an Olympic gold medallist. Coulon’s gym became a hub for young hopefuls and visiting champions alike.

Even in old age, Coulon delighted in demonstrating his “unliftable” trick. Muhammad Ali himself tried and failed to raise him in the 1960s. The image of the towering Ali, straining against the calm, birdlike Coulon, became part of his legend.

Johnny Coulon died in 1973 at the age of 84. Though his name may not be as widely known today as other boxing champions, his life story bridges two worlds: the brutal honesty of the boxing ring and the playful deception of vaudeville theatre.

Why Johnny Coulon Still Fascinates

Johnny Coulon’s story reminds us of the blurred lines between sport, science, and spectacle. As a boxer, he showed that skill and intelligence could overcome size. As a performer, he demonstrated that with the right mix of physics, psychology, and misdirection, even the most powerful men could be made to look powerless.

In an age where “influencers” build careers on viral tricks, Coulon feels oddly modern. He wasn’t just a fighter, he was a master of branding before the word existed.

And perhaps that’s why he remains so compelling. Johnny Coulon, “The Unliftable Man,” stood as proof that strength isn’t always about size, and mystery isn’t always about the supernatural. Sometimes, it’s simply about knowing more than the other guy and knowing how to put on a show.

Sources

Cyber Boxing Zone, “Johnny Coulon.” http://www.cyberboxingzone.com/boxing/coulon.htm

BoxRec, “Johnny Coulon.” https://boxrec.com/en/proboxer/08468

Chicago Tribune, “Johnny Coulon Dies; Former Bantamweight Champion.” (October 30, 1973) https://www.chicagotribune.com

Houdini, Harry. Magician Among the Spirits. Harper & Brothers, 1924. (Comment on Coulon’s act as “hokum”)

New York Times, “Johnny Coulon, ‘Unliftable Man,’ Dies at 84.” (October 30, 1973) https://www.nytimes.com

Nat Fleischer, The Ring Record Book and Boxing Encyclopedia. The Ring, multiple editions.

The Gazette (Montreal), “Ali Baffled by ‘Unliftable Man’ in Chicago.” (1960s coverage of Coulon’s demonstration with Muhammad Ali)

Evening Independent (St. Petersburg, FL), “Coulon’s Trick Still Stumps Strong Men.” (August 1959).

Comments