When Syphilis Was a Death Sentence: The Haunting Reality Before Penicillin

- Daniel Holland

- Jun 21, 2025

- 7 min read

Updated: Aug 8, 2025

Imagine sitting in a dingy consulting room sometime around 1900. You’ve come to see a doctor because your skin has erupted in angry sores, your joints ache unbearably, and there’s a constant buzzing in your ears. The diagnosis, whispered with discomfort, is syphilis. There is no easy cure, no guarantee of recovery, and the treatment itself might kill you faster than the disease.

This was once the grim reality for millions. Long before the humble penicillin mould transformed medical history, syphilis was one of the most dreaded diseases in Europe and beyond. Its impact shaped literature, moral codes, medical practice, and even social stigma — leaving behind a trail of heartbreak, disfigurement, and, for some, infamy.

The Early Spread: Blame It On The Neighbours

Syphilis probably didn’t originate in Europe — at least that’s the prevailing theory, though historians still argue about it with near-religious fervour. The so-called “Columbian hypothesis” holds that Christopher Columbus and his sailors unwittingly brought the infection back from the Americas after their first voyages in the 1490s. Supporting this idea are skeletal remains found in pre-Columbian burials in the New World that show signs of treponemal disease, but pinning down whether these were exactly the same strain is a scientific puzzle that continues to spark academic fistfights to this day.

What is indisputable is how quickly syphilis exploded across Europe once it arrived. Within a few years of Columbus’s return, reports of a horrifying new venereal disease cropped up wherever armies and mercenaries travelled. The most infamous early outbreak was among the besieging forces of Charles VIII of France during his invasion of Naples in 1495. Soldiers on campaign, with few opportunities for hygiene and plenty of opportunities for brothels, became perfect vectors. By the time they limped back home, they carried syphilis with them, gifting it to every town and port en route.

Naturally, no nation wanted to take the blame for this embarrassing scourge. So they simply blamed the neighbours: the Italians dubbed it mal francese, the French disease; the French pointed at the Neapolitans; the Poles blamed the Germans; the Russians blamed the Poles, a pattern of national finger-pointing that would persist for centuries. In England, it was sometimes euphemistically called “the pox”, which conveniently lumped it in with other ailments without having to say too much about how one caught it.

Unlike killers like smallpox or the bubonic plague, syphilis was insidious rather than swift. At first, it would make its presence known through a small sore at the site of infection — a chancre — which might heal on its own, lulling sufferers into a false sense of security. Weeks or months later, a rash might break out, covering the trunk and limbs, sometimes accompanied by fever and malaise. This stage might also vanish spontaneously. Then, in the so-called “latent” phase, the disease could go into hiding for years, even decades, with no obvious signs.

But its final act was the most feared. In its late stage, what doctors came to know as tertiary syphilis, the infection could erupt inside the body like a time bomb. It devoured soft tissues, ate away at bones, and riddled the heart and major arteries with aneurysms. Most dreadful of all was neurosyphilis, where the bacterium infiltrated the brain and spinal cord, leading to severe dementia, psychosis, paralysis, and eventually a lingering death.

This slow, shape-shifting progression made syphilis baffling for physicians of the medieval and Renaissance periods. There were no microscopes yet to see the tiny corkscrew-shaped bacterium behind it. Theories abounded: some blamed imbalances in the four humours, others suspected it was a curse from God for licentious living. Treatments were equally speculative, combining faith, folklore, and whatever poisonous concoctions seemed to force the disease back into remission — at least for a while.

In this murky gap between folk belief and fledgling science, syphilis took root as one of Europe’s great social terrors — a disease that shamed families, ruined reputations, and inspired lurid woodcut illustrations of pox-ridden sinners reaping the wages of moral laxity. Its reputation as both punishment and plague ensured that its sufferers were pitied and vilified in equal measure, a tragedy compounded by the fact that for centuries, nobody really understood what they were dealing with.

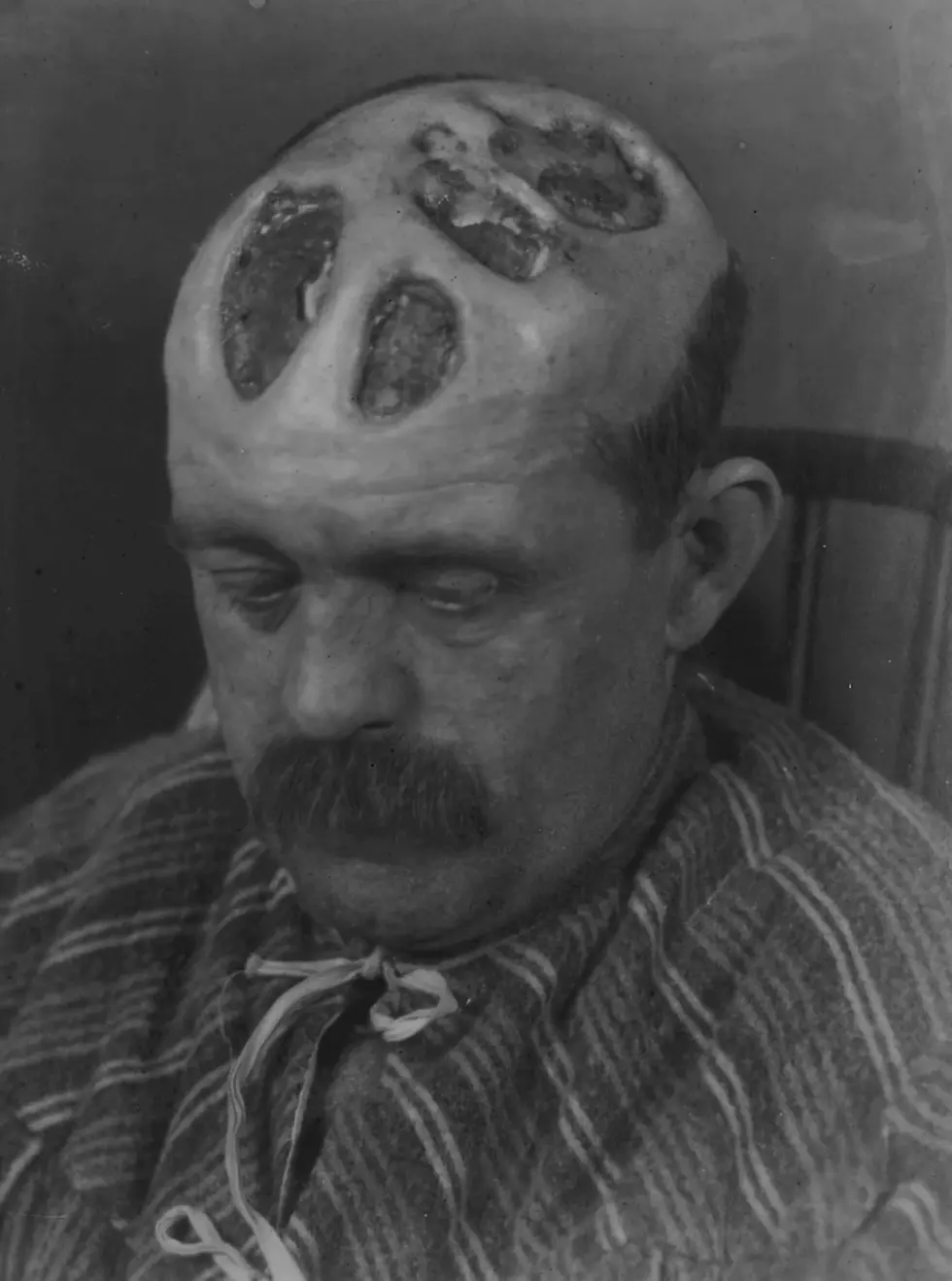

Faces Forgotten: What The Photos Show Us

Many old medical photographs survive of patients whose lives were unrecognisably warped by syphilis. They are hard to look at, but they tell truths that words alone cannot.

A common sight was the so-called “saddle nose”, where the infection devoured the cartilage, leaving a collapsed bridge and gaping nasal cavity. Other patients had gaping ulcers on their scalps, cheeks and mouths. The final stage, neurosyphilis, was perhaps the cruellest. Patients lost their sight, their sense of balance, and often their sanity. They’d stagger in the streets, accused of drunkenness or lunacy.

For some, these visible signs meant exile from polite society. People whispered about promiscuity and moral decay. In reality, syphilis didn’t discriminate. It claimed nobles, poets, soldiers, sex workers, and unsuspecting wives alike.

How Doctors Tried To Help — And Sometimes Did More Harm

Lacking any real cure for centuries, physicians resorted to treatments that, by today’s standards, seem more suited to an alchemist’s workshop than a medical clinic. Mercury was the undisputed favourite. The old quip — “A night with Venus, a lifetime with Mercury” — was no idle jest; it summed up the cruel bargain sufferers made in the hope of relief.

Patients might sit in special vapour cabinets, sweating profusely as mercury fumes swirled around them, the idea being that poisonous vapour would ‘sweat out’ the disease through the skin. Others endured topical rubs, where a thick mercury paste was applied to sores, sometimes under bandages that would be left on for days. If that failed, and it often did, patients would be given mercury pills to swallow, guaranteeing that the poison reached every organ.

In practice, the ‘cure’ proved nearly as horrific as the disease. Mercury would inflame the gums, loosen teeth until they fell out, damage the kidneys beyond repair, and occasionally drive patients into delirium. Some unfortunate souls endured cycles of syphilis symptoms punctuated by mercury poisoning, becoming progressively weaker each time.

Desperate for alternatives, European doctors turned their eyes westwards. When Spanish conquistadors brought back guaiacum wood from the Caribbean in the early 16th century, it was marketed as a wonder drug — ‘holy wood’ capable of purging the infection. Patients drank guaiacum-infused decoctions or sweated it out in ‘sweating boxes’, which were essentially crude saunas lined with blankets and hot stones. Royal courts and wealthy households stocked it, but in truth, it offered little more than placebo comfort.

As medical science edged towards modernity, the hunt for a true cure gained urgency. At the dawn of the 20th century, the German scientist Paul Ehrlich, working with Sahachiro Hata, made a historic leap forward. In 1909, they developed Salvarsan — or ‘compound 606’ as it was first known — an arsenic-based chemical designed to kill the syphilis bacterium without killing the patient.

Salvarsan was hailed as a breakthrough, a ‘magic bullet’ before the term was fashionable. For the first time, doctors had something that actually targeted the cause, not just the symptoms. But it came with its own hazards: it was tricky to prepare, required precise injections, and could cause severe liver damage or allergic reactions. Patients often needed multiple courses, and the treatment demanded skill and careful monitoring. Nonetheless, compared to the centuries of fumbling with mercury and miracle woods, Salvarsan was a giant step closer to salvation — a step that would ultimately culminate in the penicillin revolution decades later.

Syphilis In Culture: A Scandalous Open Secret

Syphilis shaped the art, poetry and moral panics of its time. Some historians argue that the grim portrayal of corruption and decay in works by writers like Baudelaire or artists like Edvard Munch reflect its shadowy presence in bohemian circles.

In polite society, the disease was whispered about in coded terms: “blood disorder”, “bad blood”, “family weakness”. Sometimes entire family trees were quietly destroyed by inherited congenital syphilis, children born blind or deformed, carrying the disease of a father’s past indiscretion.

Even into the 20th century, syphilis kept its sinister hold. In Britain, it fuelled eugenics debates and moral crusades. In the United States, shameful human experiments cast a long stain on public health history: the infamous Tuskegee Study saw hundreds of Black men denied penicillin treatment well into the 1970s, just so doctors could watch the disease’s final stages. In Guatemala, researchers deliberately infected people to test treatments, leaving thousands harmed. These ethical breaches are shocking, even today.

A Chance Discovery That Changed Everything

The true turning point came from something left on a messy petri dish. In 1928, Alexander Fleming noticed that a stray mould killed bacteria on his culture plates — penicillin. But it took a world war to push penicillin into mass production and widespread use.

By the 1940s, soldiers with venereal diseases were given penicillin, and for the first time in history, syphilis could be cured swiftly and safely. What had once been a life sentence now became an injection and a follow-up. Within a few years, syphilis wards in hospitals emptied. Mortality plunged.

Still With Us — But Not Like Before

Today, syphilis is far from extinct. It remains a global health problem, especially where healthcare access is poor. Outbreaks still pop up in big cities, reminding us that human nature, and human vulnerability, haven’t changed all that much.

But the horror-show images from before the penicillin era remind us what can happen when medicine lags behind disease. They are not just grotesque oddities for textbooks. They are testimonies to lives lived in pain and stigma, and to the quiet, relentless fight that ordinary people and pioneering doctors waged against an invisible foe.

So, next time you get offered antibiotics for something minor, spare a thought for those who never had that chance — and for the accidental genius of a forgotten mould that turned a medieval nightmare into a curable infection.

Comments