The Unsolved Mystery of the Oklahoma Girl Scout Murders

- Daniel Holland

- Jun 13, 2025

- 6 min read

Updated: Aug 9, 2025

In the quiet hours before dawn on 13 June 1977, the peaceful summer routine at Camp Scott in Mayes County, Oklahoma, was shattered by a horrific discovery. Three young girls, Lori Lee Farmer, aged 8; Michele Heather Guse, 9; and Doris Denise Milner, 10, had been raped and murdered, their bodies left in sleeping bags along a trail leading to the camp's shower facilities. The case would go on to grip the state, unravel in the courts, and remain officially unsolved nearly fifty years later.

Camp Scott: A Beloved Institution

Camp Scott had been run by the Girl Scouts since 1928. Nestled in the forested hills just two miles from the small town of Locust Grove and 50 miles from Tulsa, it was seen as an ideal place for girls to experience nature, camaraderie, and personal growth. It was also isolated, perfect for camping, but, as events would show, vulnerable too.

The 1977 season had only just begun. On Sunday, 12 June, 130 Girl Scouts were welcomed to the camp. That evening, the girls settled into their tents, including Lori, Michele, and Doris, who were placed together in Tent #7 of the Kiowa unit. Their tent was situated farthest from the counsellors' quarters and partially obscured by a nearby shower block. It was also only 86 yards from the staff tent, close enough, one might think, for sounds to travel.

First Night in the Woods

Doris Milner was new to camp life and one of the few Black girls attending that session. Though nervous at first, she quickly bonded with Lori and Michele. As a storm passed overhead, the three girls shared songs and stories before bed. According to their counsellor, Carla Wilhite, they were “three of the quietest kids,” but their tent was “just as loud and lively” as any.

That night, campers and staff reported unsettling activity. At around 1:30 a.m., one counsellor went out to investigate moaning sounds coming from the woods but returned without discovering the source. At 2 a.m., a camper in Tent #7 was startled awake by a beam from a flashlight shining into her face. Around 3 a.m., someone was heard crying, “Momma, Momma.” Nearby, a local landowner noticed unusual traffic on a remote road near the camp between 2:30 and 3 a.m. In hindsight, these eerie details painted a troubling picture.

The Grisly Discovery

At around 6 a.m. on Monday morning, Carla Wilhite, on her way to the showers, saw a sleeping bag lying in the woods near Tent #7. Inside it was the body of Doris Milner. Believing at first that it was a tragic accident, she rushed to get help. Only when the camp director and nurse unzipped the other sleeping bags did they find Lori and Michele, their small bodies crumpled at the bottom.

All three girls had been raped. Doris had been strangled, while Lori and Michele had been bludgeoned to death. Two had been placed inside sleeping bags; one had not. Blood covered parts of the tent, and it appeared that towels and mattresses had been used to wipe it around. Authorities also recovered a large red torch atop the bodies, with a smudged fingerprint on the lens, and a size 9.5 boot print found in the blood.

The camp was evacuated by that afternoon. Buses returned the rest of the children to Tulsa, with parents reunited with their daughters around 2:15 p.m. For the families of the three girls in Tent #7, life would never be the same.

A Chilling Warning Ignored

Shockingly, this wasn’t the first sign of trouble at Camp Scott that year. In April, just two months before the camp opened, a counsellor’s belongings had been disturbed during training. Doughnuts were stolen, and inside the empty box was a handwritten note that read:

“We are on a mission to kill three girls in tent one,” signed, chillingly, “The Killer.”

It was treated as a prank and discarded.

After the murders, investigators would return to that note with grim suspicion.

Enter Gene Leroy Hart

Attention quickly turned to a fugitive named Gene Leroy Hart. A local man and member of the Cherokee Nation, Hart had escaped from the Mayes County Jail in 1973. He had been convicted of raping and kidnapping two pregnant women and burglary, and had vanished into the nearby hills.

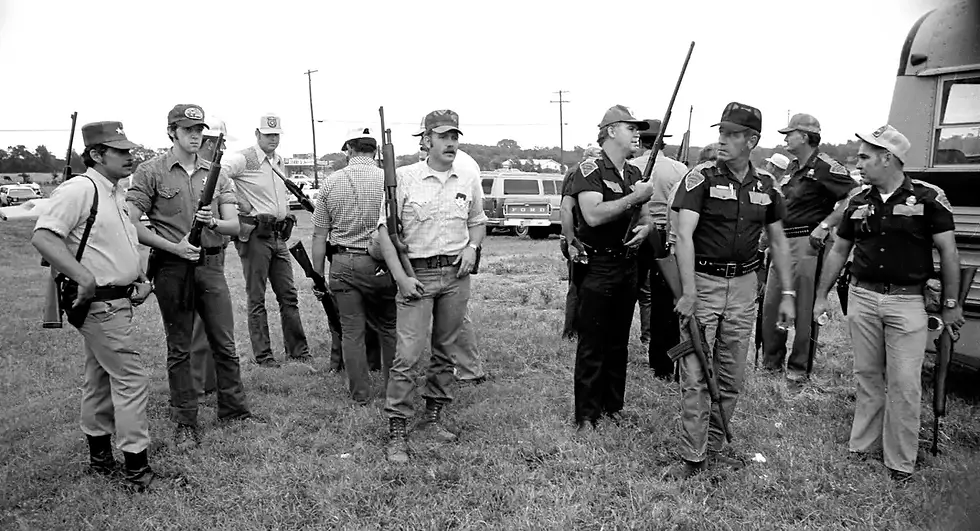

Born and raised less than a mile from Camp Scott, Hart was found a year after the murders hiding at the home of a Cherokee medicine man. His arrest followed what became the largest manhunt in Oklahoma’s history, involving more than 40 FBI agents and costing over a million dollars.

A cave two miles from the camp was found containing a flashlight battery, photographs of women (allegedly stolen from Hart’s earlier victims), and glasses believed to belong to one of the camp staff. On the wall of the cave, someone had scrawled, “The killer was here. Bye bye fools. 77-6-17.”

The Trial and Acquittal

Hart’s trial began in March 1979 and lasted several weeks. The prosecution pointed to evidence like the eyeglasses, hair found on duct tape at the scene, and items found in the cave. The defence argued the glasses had been taken from Hart’s previous victims and that other evidence had been planted. They also suggested another suspect: a man named William Stevens, a convicted rapist reportedly seen at Camp Scott days before the murders.

Dean Boyd, a local waitress, testified she had served a nervous man at her diner the morning after the murders, and a friend of Stevens claimed he had lent him a flashlight matching the one found at the scene. He also alleged Stevens had confessed to the crime months later.

But none of it was enough. The jury deliberated for only five minutes before acquitting Hart. Though he wasn’t cleared of his previous crimes, and still had a 308-year sentence to serve, justice in the Girl Scout case was never formally delivered.

On 4 June 1979, just a few months after the verdict, Gene Leroy Hart collapsed and died of a heart attack while jogging in the prison yard.

DNA Testing and Lingering Questions

In 1989, DNA testing of semen samples from the scene showed three out of five probes matched Hart’s DNA. Statistically, one in 7,700 Native Americans could have been a match, which wasn’t enough to close the case definitively. More testing in 2008 was inconclusive due to deterioration of the evidence.

Then, in 2017, the sheriff of Mayes County raised $30,000 in donations for further testing. By 2019, new results emerged — this time strongly suggesting Hart’s involvement. But the findings weren’t made public until 2022, when the victims’ families requested transparency. “Unless something new comes up... I am convinced of Hart’s guilt,” said Sheriff Mike Reed.

Still, legally, the case remains open. Officially, the Oklahoma Girl Scout Murders are unsolved.

Legal Aftermath

The families of the victims pursued a civil suit against the Magic Empire Council, which ran the camp. The lawsuit, seeking $5 million, alleged negligence — particularly regarding the ignored threat note and the tent’s distance from staff supervision. In 1985, the jury ruled in favour of the Council.

In the years since, the parents channelled their grief into activism. Michele Guse’s father helped enact the Oklahoma Victims’ Bill of Rights and founded the Oklahoma Crime Victims Compensation Board. Lori Farmer’s mother, Sheri, launched the state’s chapter of Parents of Murdered Children.

The camp itself never reopened. Camp Scott stands abandoned, overgrown, and silent, its legacy frozen in time.

A Dark Chapter Without Closure

Despite advancements in forensic science and the passage of time, the deaths of Lori, Michele, and Doris remain officially unsolved. Their story has been the subject of books, documentaries, podcasts, and public debate. Even Broadway star Kristin Chenoweth, who was supposed to attend the same camp session but fell ill, later said the event profoundly shaped her.

What happened that night in June 1977 remains one of America’s most disturbing unsolved crimes. Whether or not conclusive justice will ever emerge, the memory of those three young girls, and the questions surrounding their deaths, continues to echo through the woods of Oklahoma.

Comments