The Mad, Brilliant Military Tactition, Major General Orde Charles Wingate

- Daniel Holland

- Mar 28, 2023

- 6 min read

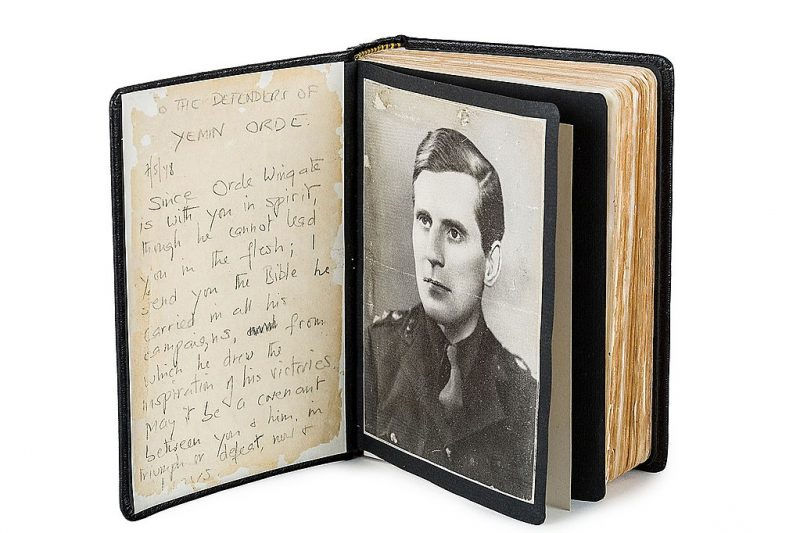

What do a man who wore an alarm clock on his wrist, munched raw onions like apples, and once strutted out of the shower to bark orders wearing nothing but a cap and a scrubbing brush have in common with Winston Churchill’s war strategy? The answer is Major General Orde Wingate – a brilliant, eccentric, controversial British officer whose ideas shaped guerrilla warfare in the 20th century.

Churchill once called him “one of the most brilliant and courageous figures of the second world war … a man of genius who might well have become also a man of destiny”. Others, like Field Marshal Montgomery, were less kind, saying he was “mentally unbalanced and that the best thing he ever did was to get killed in a plane crash in 1944”.

Few military men divide opinion like Wingate. Was he a visionary who inspired Israel’s defence forces and helped liberate Ethiopia? Or a dangerous fanatic whose Chindit operations in Burma caused needless suffering? Let’s dig into his extraordinary story.

A Strict Childhood

Orde Charles Wingate was born on 26 February 1903 in Naini Tal, India, into a strict Plymouth Brethren family. His father, Colonel George Wingate, was deeply religious and believed Bible study was the only foundation for life. Orde and his six siblings were raised on scripture, problem-solving exercises, and little in the way of a normal childhood.

He never quite fit in with others. At Charterhouse school, he was kept apart from boarding life. His family encouraged independence, toughness, and thinking outside the box – all traits that would later fuel his odd methods of leadership.

By 1921, Wingate entered the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich. Even here, his reputation for defiance was obvious. During a hazing ritual, when junior cadets were supposed to run through a gauntlet of seniors whipping them with knotted towels, Wingate instead dared each senior to strike him. None did. He then calmly jumped into the icy cistern at the end.

A Taste for Harsh Lands

Wingate thrived where others wilted. Posted to Sudan in 1928, he patrolled against slave traders and ivory poachers, often preferring ambushes over traditional patrols. He loved the bush, hated HQ life, and antagonised other officers with his bluntness.

He even led an expedition in 1933 to look for the “lost oasis” of Zerzura and the army of Cambyses mentioned by Herodotus. He didn’t find them, but the trek hardened his body and sharpened his endurance. These extreme tests of will were a recurring theme: Wingate believed toughness and sheer mental grit could overcome almost anything, including disease.

Palestine and the Special Night Squads

Wingate’s most notorious pre-war posting came in 1936, to British Mandate Palestine. Unlike many of his peers, he was openly pro-Jewish, believing it was his Christian duty to support the creation of a Jewish state.

He set up the Special Night Squads – joint units of British soldiers and Jewish Haganah fighters who struck Arab guerrillas under cover of darkness. Their tactics were brutal. As historian Yoram Kaniuk noted:

“The operations came more frequently and became more ruthless. The Arabs complained to the British about Wingate's brutality and harsh punitive methods. Even members of the field squads complained... Wingate would behave with extreme viciousness and fire mercilessly. More than once he had lined rioters up in a row and shot them in cold blood. Wingate did not try to justify himself; weapons and war cannot be pure.”

Wingate even used torture: forcing sand into mouths, throwing men into crude oil pools, and yelling at Jewish fighters for not using bayonets properly against “dirty Arabs.” Yet Zionist leaders like Moshe Dayan revered him, later saying Wingate had “taught us everything we know”.

His open political support for Zionism got him sacked in 1939, but in Israel today his name lives on in streets, schools, and the Wingate Institute.

Gideon Force and Ethiopia

During WWII, his old patron General Wavell gave him a new chance – leading a guerrilla band against Italian forces in Ethiopia. Wingate called it Gideon Force, after the biblical judge who beat a vast army with only a handful of men.

With just 1,700 troops, British, Sudanese, Ethiopian, and a handful of Haganah veterans, Wingate harassed supply lines, took forts, and drove the Italians to surrender 20,000 men. Emperor Haile Selassie hailed him as a liberator, and Wingate rode into Addis Ababa at the emperor’s side in 1941.

But behind the victories, cracks showed. Depressed and suffering malaria, Wingate overdosed on Atabrine and stabbed himself in the neck in a suicide attempt. He was saved, but the story cemented his reputation as unstable.

The Chindits in Burma

If Wingate is remembered for anything, it’s the Chindits.

Sent to Burma in 1942, he proposed long-range penetration units that would slip behind Japanese lines, supplied by air, and attack railways and communication hubs. His force, 77th Brigade, took the name “Chindits” from a Burmese mythical lion.

Wingate’s methods were eccentric. He lived with his men in the jungle, encouraged beards, ate raw onions as insect repellent, and sometimes held meetings stark naked. He believed soldiers could fight off disease with willpower, medical officers strongly disagreed.

The first Chindit mission, Operation Longcloth in 1943, achieved some sabotage but cost a third of the men, many to starvation and disease. Still, it caught Churchill’s attention. At the Quebec Conference, Wingate pitched his ideas directly to Allied leaders. They approved, and he was promoted to acting major general.

Operation Thursday in 1944 saw Chindits flown in by glider and Dakota transport, carving out strongholds deep in Burma. They disrupted Japanese supply lines and helped slow the enemy advance toward Kohima and Imphal – two of the most decisive battles of the Burma Campaign.

General Slim later downplayed Wingate’s role, but Japanese commander Mutaguchi Renya admitted: “The Chindit invasion ... had a decisive effect on these operations ... they drew off the whole of 53 Division and parts of 15 Division, one regiment of which would have turned the scales at Kohima.”

Death in the Jungle

On 24 March 1944, Wingate boarded a USAAF B-25 Mitchell to inspect Chindit bases. Against the pilot’s warning, he allowed two British correspondents aboard, overloading the plane. It crashed in the hills of Manipur, killing all ten on board.

Initially buried in a common grave near the crash site, the remains were reinterred several times before Wingate and his companions were finally laid to rest at Arlington National Cemetery in 1950.

Eccentricities and Reputation

Wingate’s oddities became legend:

Wearing an alarm clock as a wristwatch.

Eating garlic and onions off a string.

Holding naked staff meetings.

Once living on grapes and onions alone.

Lord Moran, Churchill’s doctor, wrote that Wingate “seemed to me hardly sane – in medical jargon a borderline case.” Historian Max Hastings said Churchill quickly realised his protégé was “too mad for high command.”

Yet many soldiers who served under him swore by his genius. General Slim, despite later criticisms, once said: “The number of men of our race in this war who are really irreplaceable can be counted on the fingers of one hand. Wingate is one of them.”

Legacy

Wingate remains one of WWII’s most divisive figures. To Israelis, he’s a hero of Zionism. In Ethiopia, he’s remembered as a liberator. In Britain, his reputation swings between eccentric visionary and dangerous zealot.

As historian Simon Anglim put it, Wingate may be “the most controversial British general of the Second World War”. His Chindits pioneered tactics that influenced special forces from Indonesia to modern counterinsurgency strategies.

Whether mad, brilliant, or both, Orde Wingate was a man impossible to ignore – a soldier whose onions, alarm clocks, and sheer audacity left their mark on history.

Sources

Bierman, John & Colin Smith. Fire in the Night: Wingate of Burma, Ethiopia, and Zion.

Hastings, Max. Finest Years: Churchill as Warlord 1940–45.

Mead, Peter. Orde Wingate and the Historians.

Rooney, David. Wingate and the Chindits.

Sykes, Christopher. Orde Wingate.

Warner, Philip. Orde Wingate.

Official History: I.S.O. Playfair & S. Woodburn Kirby.

Comments