Nicolae Minovici: The Romanian Doctor Who Hanged Himself for Science

- Cassy Morgan

- Aug 23, 2025

- 5 min read

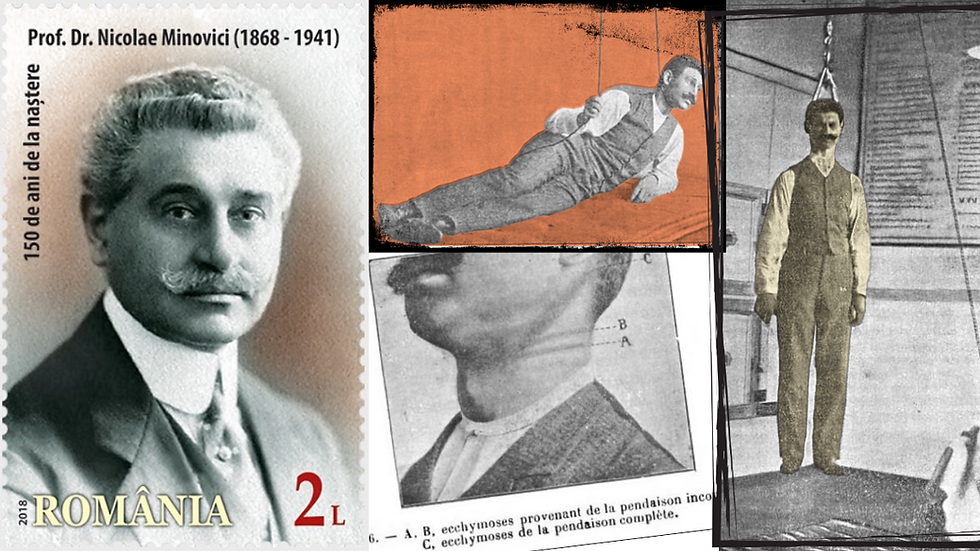

There are doctors who dedicate their lives to understanding illness, others who throw themselves into public health campaigns, and then there are those rare figures who go far beyond the call of duty. Nicolae Minovici was one of those. A Romanian forensic scientist at the turn of the twentieth century, Minovici didn’t just study death by hanging from afar—he became his own test subject. Quite literally, he tied a noose around his neck, pulled it tight, and recorded what happened.

It sounds reckless today, and in many ways it was. But his work was part of a broader attempt to understand crime, punishment, and the limits of human endurance. And yet Minovici’s life wasn’t defined solely by these strange experiments. He was also a humanitarian, a patron of folk art, and a pioneer of emergency medical services in Romania. His story is one of science, sacrifice, and a deep curiosity about the human condition.

The Curious Beginnings of a Forensic Scientist

Nicolae Minovici was born in 1868 in Romania, into a period of rapid change. The late nineteenth century was a time when science was pushing into areas once left to philosophy and folklore. Forensic medicine—combining legal processes with medical knowledge—was a young but growing discipline, and Minovici quickly found his calling there.

By the early 1900s, he was a professor of forensic science at the State School of Science in Bucharest. His academic focus was death, more specifically, how to determine cause, circumstance, and physical details surrounding suspicious deaths. Hanging was a common method of both suicide and execution at the time, and it fascinated Minovici.

But reading about it wasn’t enough. He wanted to know, in his own body, what it felt like. As he put it in his 1904 book Study on Hanging (Studiu asupra spânzurării), “To truly understand death, one must know its approach.” That meant stepping into the noose himself.

The First Experiments: A Pulley and a Noose

Minovici’s early attempts were cautious. He set up a device in his study: a noose tied in a hangman’s knot, threaded through a pulley on the ceiling, with the loose end at hand. He lay on a cot, slipped the rope around his neck, and tugged.

The result was immediate and brutal. His face flushed purple, his vision blurred, and he heard a strange whistling in his ears. He lasted just six seconds before he felt his consciousness fading and quickly stopped.

Instead of deterring him, this first test spurred him on. If six seconds could reveal so much, what could longer exposure show?

Assisted Hangings: Swinging in the Air

For the next stage, Minovici enlisted assistants. With them holding the other end of the rope, he placed the noose around his neck and gave the signal. They pulled hard, lifting him into the air.

This was no gentle experiment. Suspended several metres above the ground, his airway constricted instantly. His eyes squeezed shut, his throat tightened, and he could barely signal to be released.

The first attempt lasted only seconds. But Minovici persisted. In repeated trials, he was hoisted again and again, each time pushing the limits of how long he could remain conscious. Eventually, through what he called “practice,” he managed to endure twenty-five seconds swinging by his neck. It was, he admitted, an agony like no other.

The Final Attempt: The Real Hangman’s Knot

There was still one variable left, using a true, constricting hangman’s knot. This was the knot used in real executions, designed to crush the windpipe and snap the neck. Minovici wanted to see the difference.

He set up the rope, tied the knot, and signalled to his assistants. The moment the knot tightened, he felt as though fire ripped through his throat. The pain was so overwhelming that he waved frantically to stop the experiment. He had lasted only four seconds.

Remarkably, in this final test, his feet had never even left the floor. Yet the damage was lasting. For an entire month afterwards, swallowing food was painful. He had taken his body to the brink and left it scarred.

Twelve Times in the Noose

Altogether, Nicolae Minovici performed twelve hanging experiments on himself. He meticulously documented each one: the length of time, the placement of the knot, and the symptoms he experienced. He described the blurred vision, the swelling of his face, the ringing in his ears, and the tingling sensations in his limbs.

He also carried out experiments on volunteers—though not by hanging them. Instead, he compressed their carotid arteries and jugular veins for five seconds at a time, noting the flushed faces, heat sensations, and tingling they reported afterwards.

To modern readers, these methods sound reckless. But in his time, Minovici was pushing the limits of forensic science. His detailed observations helped build a more precise understanding of what hanging did to the body. His 200-page book, first published in Romanian in 1904 and then in French in 1905, became a key text in forensic studies.

Beyond the Noose: A Life of Service

If Minovici had stopped at his hanging experiments, he would have been remembered as one of medicine’s strangest martyrs. But his career was far broader, and far more humane.

He was one of the first in Romania to set up a modern ambulance service. Before his efforts, emergency medical care in the Balkans was almost non-existent. He financed the service himself for years, making sure the poor and vulnerable could access urgent help. In his lifetime, he oversaw care for more than 13,000 homeless people and opened shelters for single mothers who had nowhere else to turn.

He even served as mayor of the Băneasa district of Bucharest, where he improved sanitation, fountains, and night shelters. His work was rooted in the belief that medicine wasn’t just about studying death, it was about preserving life.

A Passion for Folk Art

Outside of medicine, Minovici had another love: Romanian folk culture. He collected traditional art, crafts, and costumes, amassing a large personal collection. In 1906, he opened his villa in Bucharest to the public as a folk art museum.

That villa, built by architect Cristofi Cerchez, still stands today as the Nicolae Minovici Folk Art Museum. Visitors can explore rooms filled with ceramics, textiles, and icons from across Romania, a reminder that this doctor who risked his life in pursuit of science also celebrated the beauty of his nation’s traditions.

Death and Legacy

Nicolae Minovici never married. When he died in 1941, from an illness that affected his vocal cords, he left his estate, including his villa and art collection, to Romania. The street beside the museum now bears his name, a small nod to a man whose life was anything but ordinary.

His hanging experiments remain one of the most unusual chapters in the history of medicine. Few doctors have ever risked so much on their own bodies. Yet to define him only by those moments in the noose would miss the bigger picture. He was a pioneer of emergency medicine, a reformer, and a preserver of culture.

As one Romanian medical historian put it, “Nicolae Minovici hanged himself so that others might live.”

Conclusion

Nicolae Minovici’s story is hard to categorise. Was he a reckless thrill-seeker, a martyr to science, or a visionary public servant? In truth, he was all three. His self-experiments might shock us today, but they were part of a broader, lifelong devotion to understanding human life in all its fragility and strength.

Whether through a rope and a noose, an ambulance service, or a museum of folk art, Minovici sought knowledge and gave back to his community. And that, perhaps, is the most enduring legacy of all.

Sources

Minovici, N. Studiu asupra spânzurării (Study on Hanging), 1904 (Romanian edition)

Minovici, N. Étude sur la pendaison, 1905 (French edition)

Petrescu, Dr. M. – Forensic Medicine in Romania: History and Development, Romanian Journal of Legal Medicine, 2009

Nicolae Minovici Folk Art Museum – Bucharest Museums Guide

https://muzeulbucurestiului.ro/muzeul-de-art-populara-nicolae-minovici

Marinescu, C. – The Minovici Brothers and Their Contribution to Romanian Medicine, Revista de Istorie a Medicinei, 2010

Comments