James Jameson: The Whisky Heir That Bought A Girl Just To Watch Her Be Eaten By Cannibals

- Aug 17, 2023

- 12 min read

There are moments in history that begin with a shrug and end with a shudder. The story of James Jameson, heir to an Irish whiskey fortune and naturalist by ambition, is one of those moments. He joined a celebrated African expedition as a gentleman observer and left it a figure of horror, a man whose sketches and silence became evidence in one of the most disturbing episodes of Victorian exploration. What follows is not a lurid tale for its own sake but a careful reading of the words left behind, the testimonies sworn, and the choices made when power and curiosity walked into a house by the Congo and never quite walked out again.

“It is horrible to watch these men slowly dying before your face, and not be able to do anything for them.”

The line above sits in Jameson’s diary like a flare in a dark sky. It speaks to the slow privations of the Emin Pasha Relief Expedition but also to the moral weather of the time. Men were dying. Choices were being made. And in June 1887, Jameson took up position at Yambuya as second in command of the rear column, a decision that placed him on the stage where his reputation would be tried in the court of public opinion long after his death.

An expedition already under strain

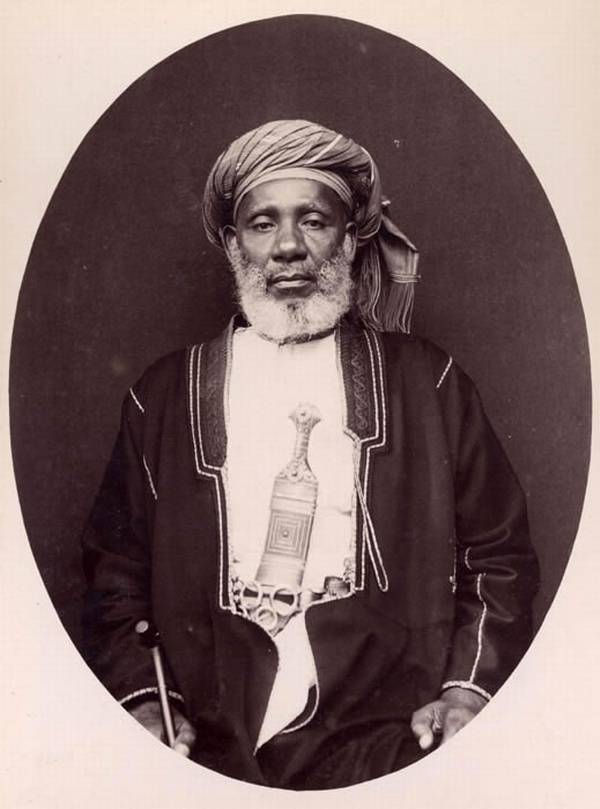

Jameson joined the Emin Pasha Relief Expedition by formal agreement on 20 January 1887 and paid one thousand pounds into the venture. He was engaged as a naturalist. The expedition’s field commander was Henry Morton Stanley whose reputation for relentless drive preceded him. Stanley worried that Jameson looked “physically frail,” yet he agreed to the appointment after hearing of Jameson’s previous travels. They reached Banana in March and steamed up the Congo River. As days lengthened into weeks, Jameson discovered what many had learned before him. Stanley could be a harsh leader and a hard man to satisfy. When Stanley fell ill with dysentery he placed blame on Jameson who had responsibility for cooking and rations. That resentment lingers in the records like a taste of iron.

Physician Thomas Heazle Parke watched the party inch deeper into the Congo Basin and wrote of Jameson’s cast of mind. He noted that Jameson “was fascinated by the subject of cannibalism.” It is a line that would later carry the weight of dreadful consequence.

Yambuya and the burden of waiting

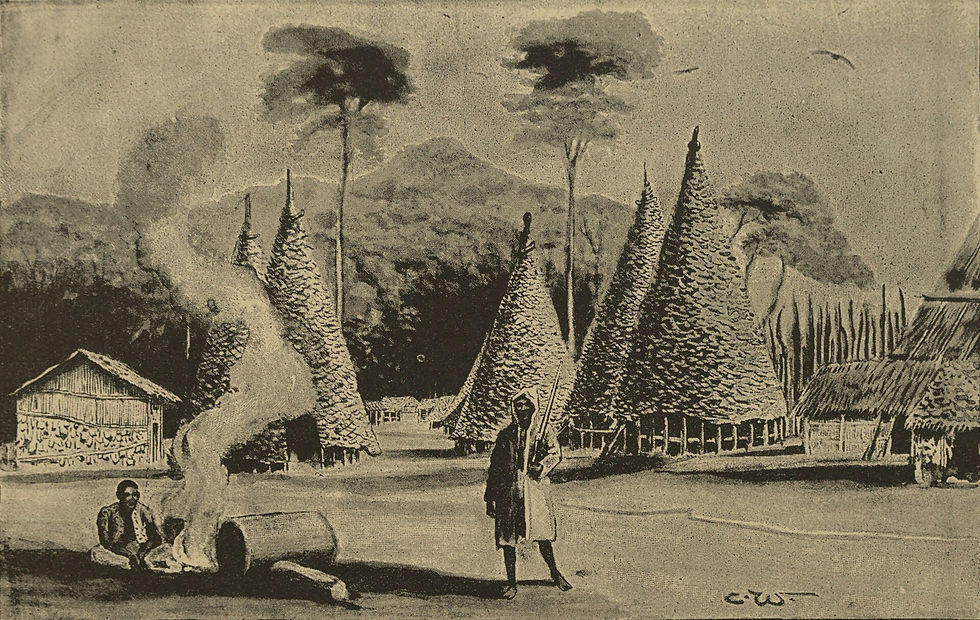

In June 1887 the expedition split. Stanley marched inland to search for Emin Pasha while Jameson remained at Yambuya on the Aruwimi River as second in command of the rear column under Major Edmund Musgrave Barttelot. The logic was simple. Stanley had hauled too much equipment for the carriers at hand. The celebrated trader Tippu Tip had promised more porters. With the reinforcements, the rear column would follow with the stores that were meant to arrive from the river mouth. In practice the promise broke like a reed in floodwater.

Tippu Tip failed to deliver. Jameson travelled to Stanley Falls in August to press the matter and returned without result. No news came from Stanley. Privation and sickness took a third of the camp. Jameson wrote:

“It is horrible to watch these men slowly dying before your face, and not be able to do anything for them.”

Relations with nearby villages collapsed. Local people refused to sell food. Their resentment was no mystery. The rear column was linked in their eyes to the slave raiding that scarred the region. The response recorded by later historians is stark. Jameson and his companions resorted to “kidnapping women and children from villages in the area,” returning them only for provisions. Food still ran short. With plantains gone and meat almost exhausted, one diary entry ended with the grim calculation:

“As a last resource we must catch some more of their women.”

It is impossible to read that sentence without feeling the cold air of a threshold crossed.

The naturalist at work and the chill behind the specimens

Jameson was formally the expedition’s naturalist. He collected birds and insects with evident dedication, and described them in gratifying detail. Yet the scientific impulse, as biographer John Bierman later put it, “had a peculiarly cold blooded dimension.” After a nearby village was attacked by slavers, a commander brought Jameson the severed head of a man. Jameson salted it for preservation and sent it to London to be dressed and mounted by a taxidermist. William Bonny later claimed he saw the grisly trophy displayed in Jameson’s house. It is an image that stains the eye.

In February 1888 Jameson set out once more to pursue porters and promises. This time he found Tippu Tip at Kasongo, far upriver. On the way back to Yambuya in May, an episode occurred that would eclipse everything else.

The Jameson Affair - A day at Riba Riba

While returning with Tippu Tip, Jameson attended festivities at the house of the chief of Riba Riba, a village by the river. Tippu Tip and his men spoke freely about cannibal banquets. According to Jameson’s diary, he replied that people at home believed such stories were only “traveller’s tales … in other words, lies.” One of Tippu Tip’s associates responded with a challenge.

“Give me a bit of cloth, and see.”

Jameson wrote that he sent for six handkerchiefs (six handkerchiefs were enough to pay for a young slave girl the Congo at that time – European cloth was a valuable import, while slaves, especially young children (for whom there was little demand except for the cannibalistic one) could be bought cheaply.) What he witnessed next, by his own account, was beyond the pale of anything he had imagined:

“I sent my boy for six handkerchiefs, thinking it was all a joke …, but presently a man appeared, leading a young girl of about ten years old at the hand, and I then witnessed the most horribly sickening sight I am ever likely to see in my life. He plunged a knife quickly into her breast twice, and she fell on her face, turning over on her side. Three men then ran forward, and began to cut up the body of the girl; finally her head was cut off, and not a particle remained, each man taking his piece away down to the river to wash it. The most extraordinary thing was that the girl never uttered a sound, nor struggled, until she fell. Until the last moment, I could not believe that they were in earnest … that it was anything save a ruse to get money out of me …

When I went home I tried to make some small sketches of the scene while still fresh in my memory, not that it is ever likely to fade from it. No one here seemed to be in the least astonished at it.”

Jameson recorded that the girl had been captured and enslaved not far from the village. The horror of the scene is not arguable. What would be argued for years was this. Did Jameson, by presenting cloth and standing by, purchase a life in order to watch it extinguished

Farran speaks, and speaks again

After the expedition and after Jameson’s death, Henry Morton Stanley chose to publish the story in the London Times on 8 November 1890. In a way it was a preemptive strike. Stanley’s management of the rear column was being savaged by survivors. If others were to blame, the blow might fall less heavily on him. His most damaging witness was Assad Farran, Jameson’s interpreter. Farran alleged that Jameson had expressed a wish to see cannibalism performed and that Tippu Tip proposed the purchase and sacrifice of a slave. Farran said Jameson handed over six handkerchiefs and a ten year old girl was produced. She was tied to a tree. Knives were sharpened. She was stabbed twice in the belly and cut in pieces. The meat was washed at the river. The rest cooked at once. Farran insisted Jameson sketched the scene as it unfolded and then coloured the drawings at leisure. He even described the sequence of the six images.

“They are six small sketches neatly done, the first when the girl was led by the man, the second when she was tied to the tree and stabbed in the belly, the blood gushing out, another when she was cut in pieces, the fourth a man carrying a leg in one hand and the knife in the other, the fifth a man with a native axe and the head and the breast, and the last a man with the inward parts of the belly.”

Farran’s claims were dynamite, and they were also unstable. In September 1888 when questioned by two committee members, he revoked his original statements. He said he had spoken from bad feeling. In this revised account Jameson stumbled upon the scene after the girl had already been killed and merely sketched the butchery. He added that such sights were common and that he had seen similar occasions himself.

The contradiction cannot be squared. One version places Jameson as purchaser and collaborator. The other makes him an appalled witness who arrived too late to intervene. Historians have tried to understand why Farran reversed himself. Some speak of pressure applied to protect the expedition from scandal. Others suggest simple opportunism. What matters for the facts is this. Farran was at Riba Riba, and despite his changes there are striking congruences between his details and Jameson’s private diary, which had not yet been published. Both accounts match on price, the girl’s age, that she was stabbed twice in the upper body, and that the sequence began in the chief’s house.

Bonny’s recollection and Stanley’s spin

Another voice entered the file. William Bonny, a member of the rear column at Yambuya, had not been present at Riba Riba but he saw the drawings and heard Jameson’s account. His memory differs from Farran’s on some important points. He does not mention a tree but he confirms the sequence from presentation to stabbing to butchery and he says the final sketch depicted the feast itself.

“Mr. Jameson showed me the sketches and described the scene in detail. I cannot now describe each of the six sketches; but they begin with the picture of the girl being brought down tied by one hand to the native, who holds in his right hand the fatal knife. He is then represented thrusting the knife into the girl, while the blood is seen spurting out. Then there is the scene of the carving up of the girl limb by limb, and of the natives scrambling for the pieces and running away to cook them, and the final sketch represents the feast.”

Bonny wrote that Jameson paid six handkerchiefs for the girl. He also stated that Jameson recounted the events to him in a way consistent with Stanley’s published account. Later writers have concluded from this that Jameson knew the girl would be killed and calmly sketched what followed. There is, however, room for uncertainty. We do not have the exact words Jameson used with Bonny. The only words we possess from Jameson are the diary passages already quoted. Those words insist that he believed he was witnessing a cruel demonstration staged to take his cloth and not a murder purchased at his request. Whether this belief can stand against his actions is the heart of the matter.

Knowledge, time, and responsibility

One can gather strands from the surviving testimony without sensational flourish. Jameson knew cannibalism existed in the region. He had recorded details of it in his diary. He had spoken with men who practised it and described their preferences for victims and methods of preparation. He had seen human remains from a feast. His colleague Herbert Ward knew as much or more and had been invited to eat human flesh by hosts who found no shame in the custom.

Given this knowledge, the moment an associate said “Give me a bit of cloth, and see,” a reasonable person might have suspected that a dreadful demonstration was at hand. Jameson handed over the cloth. He did not act to save the girl. He watched. He sketched later that day. He then spoke with Tippu Tip in the afternoon about routine expedition matters. He did not record any quarrel or protest about the act itself. There is no evidence that he sought to punish those responsible. The recording pen returned to logistics and supplies. That silence has its own weight.

The wider world around a single act

Writers who studied the Congo in that period have recorded the routine nature of the practice among specific groups. Some described the buying and butchering of slave children as everyday business. Human flesh was cookery, not sacrament, and children were held to be especially fine meat. There are accounts of children raised for slaughter. There are accounts of knife strokes and swift deaths. Years after Jameson’s visit, a European official at Riba Riba is said to have rescued a boy destined for a banquet, while another officer saw little reason to intervene because such things were normal in the surrounding villages. The Congo Free State administration did not root out the practice. Some European officers developed a taste for it themselves, if later chroniclers are to be believed.

To observe that a practice was real and widespread is not to absolve complicity. It simply sets the stage. A powerful outsider with money and escorts who pays for a victim under the pretext of a demonstration takes possession of a life and allows it to be taken. The custom of a place explains the mechanics. It does not explain the choice.

The cost of blame

Stanley’s decision to push the story into public view did not save his reputation. The furore damaged him and the larger enterprise. The very idea of privately organised non scientific expeditions into Africa lost what glamour remained. Within the expedition the rear column was already disintegrating. Tippu Tip eventually sent some porters. Discipline broke. The party split. Barttelot was killed at Unaria on 19 July. Jameson rushed to the scene and then to Stanley Falls. He saw the trial and execution of Sanga the murderer. He tried to settle a new transport arrangement and even offered to pay five hundred pounds from his own pocket to secure a reliable leader. The talks failed. Tippu Tip proposed to lead the rear guard himself but demanded twenty thousand pounds. Jameson did not have the authority to agree.

He decided to go downriver to Bangala Station where Herbert Ward waited for messages from the expedition committee. He fell ill almost at once. Ward received him in an unconscious state and watched him die of fever on 17 August. The next day he was buried on an island opposite the village, his last recorded words echoing in Ward’s memory:

“Ward! Ward! they’re coming; listen. Yes! they’re coming now let’s stand together.”

How to read the sketches now

We are left with words and with drawings we do not have. The original sketches were never published. We have descriptions of them. We have Jameson’s diary. We have Farran’s accusations and retraction. We have Bonny’s memory and Stanley’s framing. We have Jameson’s earlier lines about men dying and about catching women. We have his salt cured specimen sent to a London taxidermist. We have the afternoon in which, by his own account, he went from the murder of a child to a routine conversation with a powerful man whose trade ran on slaves and ivory.

From these materials, historians have formed different judgments about motive and sequence. Some believe Jameson knowingly purchased a girl to watch her death and to record it for scientific and personal curiosity. Others grant that he may have thought he was paying for a grim theatre and only realised too late that the theatre was real and the curtain would be a knife. What no careful reader can grant is exoneration. Power was used. Money changed hands. A child died. A white man of means looked on and later painted what he remembered.

It is tempting to make the tale a symbol and leave it there. Better to remember that this was not an isolated atrocity in an otherwise benign enterprise. It was a particularly clear window into the time. Exploration came wrapped in trade. Trade moved with force. Force fed on bodies. The sketches are the record not of a single man’s failing but of a system that made such failings easy to rationalise and easier still to forget.

The last chapters at Yambuya

When the rear guard finally moved out of Yambuya on 11 June it did so under a cloud. The Manyema porters sent by Tippu Tip proved difficult to control. The column broke into faster and slower parties. Barttelot pushed ahead while Jameson drifted behind with the rest. After Barttelot’s death and the delays that followed, Jameson’s final acts were administrative. Attempt a new contract. Seek authority from the committee. Get approval to spend the twenty thousand pounds. Secure a trusted leader who could deliver them to Lake Albert and reunite them with Stanley. Fever made a mockery of these plans. He died at Bangala Station as the river flowed on and the expedition shattered into fragments of argument and grief.

The human line that runs through it

This episode can be told as an indictment or as a warning. It is both. It indicts a culture that prized specimens over lives and called the brutality of conquest discovery. It warns us that the line between study and cruelty is thin when those being studied hold no power and those doing the studying can buy outcomes with a handful of imported cloth.

The only words we can place at the heart of the story are the words everyone agrees upon. They are the words Jameson wrote himself about the scene at Riba Riba. They are the words no editor could improve because their plainness is the measure of the affront.

“I then witnessed the most horribly sickening sight I am ever likely to see in my life.”

What happened next was not outrage. It was conversation. That is the scandal that has never quite faded.

Sources and further reading

The Emin Pasha Relief Expedition overview and James Jameson biography

John Bierman, Dark Safari and associated articles on the rear column at Yambuya

Robert B Edgerton, The Fall of the Asante Empire and essays on colonial era accounts of cannibalism and African warfare

Tim Jeal, Stanley and analysis of the Emin Pasha Relief Expedition

Thomas Heazle Parke, My Personal Experiences in Equatorial Africa

Heinrich Brode, Tippoo Tib

Guy Burrows, The Land of the Pigmies and Congo Free State accounts

Peter Forbath, The River Congo

James William Buel, Heroes of the Dark Continent

Contemporary newspaper coverage including The Times of London on 8 November 1890

Comments