The Death of Rasputin: Poison, Bullets, and One of History’s Strangest Endings

- Daniel Holland

- Aug 19

- 6 min read

Poisoned with cyanide, shot at close range, beaten savagely, and finally thrown into an icy river — and still alive? That’s the legend. The murder of Grigori Rasputin in December 1916 has become one of history’s most infamous and bizarre deaths.

But behind the folklore lies a real story of power, paranoia, and political collapse. Rasputin’s life, from Siberian peasant to mystic advisor to the Russian imperial family, was as strange as his death. And while the lurid tale of poison and bullets has become cultural folklore, the truth revealed by autopsy and eyewitnesses was rather different.

This is the full story of Rasputin’s life, his death, and the enduring myth of the Mad Monk.

A Siberian Beginning

Grigori Efimovich Rasputin was born in 1869 in Pokrovskoye, a remote village in western Siberia. The son of peasant farmers, he grew up illiterate and rough, like most muzhiks of the time. Yet even in his youth, he developed a reputation for being different: restless, intense, prone to strange visions.

As a teenager, he experienced a religious awakening. He began travelling as a wandering pilgrim, seeking monasteries and holy sites. Some claimed he was influenced by the Khlysty, a secretive sect known for ecstatic rituals, though Rasputin always denied it.

By his late twenties, he had built a small following of peasants who believed in his ability to heal, prophesy, and channel divine power. He eventually married and fathered children, but his calling lay elsewhere. Rasputin was on a path that would take him far from Siberia — to the heart of imperial power.

The Healer of the Romanovs

In 1908, Rasputin was introduced to Czar Nicholas II and Czarina Alexandra. The imperial couple’s only son, Alexei, suffered from haemophilia, a condition that left him vulnerable to life-threatening internal bleeding.

When Alexei fell gravely ill, Rasputin was summoned. Accounts suggest that he prayed, spoke calmly to Alexandra, and instructed doctors to stop their treatments of aspirin (a blood thinner, though unknown at the time). Miraculously, Alexei improved.

To Alexandra, this was proof of Rasputin’s divine gift. She became one of his most devoted supporters. Nicholas, though wary, trusted his wife’s judgement.

Rasputin soon became a fixture at court. His ability to ease Alexei’s suffering made him indispensable, but it also earned him powerful enemies.

Scandal, Rumour, and Hatred

As Rasputin’s influence grew, so did the rumours. He was often seen drunk in the capital’s taverns. Women, from peasant pilgrims to society ladies, sought his “blessings,” which sometimes blurred into sexual encounters. He preached a theology of sin and repentance that shocked the church and thrilled his followers.

The press ridiculed him with satirical cartoons, portraying him as a debauched monk manipulating the empress. Whispers claimed he was Alexandra’s lover, a scandalous accusation against a German-born empress at a time of war with Germany.

By 1914, Rasputin was one of the most hated men in Russia. Yet Alexandra clung to him. She believed he alone could save her son and guide her through a hostile court.

When Nicholas left Petrograd in 1915 to personally command Russian forces during World War I, Alexandra relied on Rasputin for advice. Ministers rose and fell on his recommendations. To many nobles and politicians, it seemed that a drunken peasant was steering the empire.

The Conspirators

By late 1916, Russia was collapsing. Military defeats, food shortages, and political chaos had turned the people against the monarchy. In this atmosphere, Rasputin became the symbol of everything rotten in Romanov rule.

A group of nobles decided that killing him was the only way to save the dynasty.

Prince Felix Yusupov – a fabulously wealthy aristocrat, married to the czar’s niece. He was notorious for his aimless lifestyle and desperate for a chance to prove himself.

Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich – Nicholas’s cousin, a decorated officer with royal blood.

Vladimir Purishkevich – a far-right politician and fierce opponent of Rasputin’s influence.

Together, they planned a murder that would become the stuff of legend.

The Night of the Murder

On the night of 29 December 1916 (old style calendar), Rasputin was invited to the Yusupov Palace in Petrograd. Yusupov told him his wife Irina wanted to meet him, though in truth she was away.

In the palace basement, Rasputin was offered cakes and wine laced with cyanide. According to Yusupov’s later memoirs, Rasputin devoured them and showed no sign of illness. Panicking, Yusupov borrowed a revolver and shot him.

But Rasputin rose again. Staggering outside into the snowy courtyard, he tried to flee. The conspirators shot him again, beat him brutally, bound his body, and threw him into the frozen Neva River.

Yusupov would later describe the scene with gothic horror:“

This devil who was dying of poison, who had a bullet in his heart, must have been raised from the dead by the powers of evil.”

This account became the most famous version of Rasputin’s death, retold in memoirs, films, and even a disco anthem by Boney M. in the 1970s.

Fact vs. Fiction

The problem is, much of it wasn’t true.

Rasputin’s daughter Maria, who later became a circus performer in Paris, dismissed the story. She claimed her father disliked sweets and would never have eaten cakes.

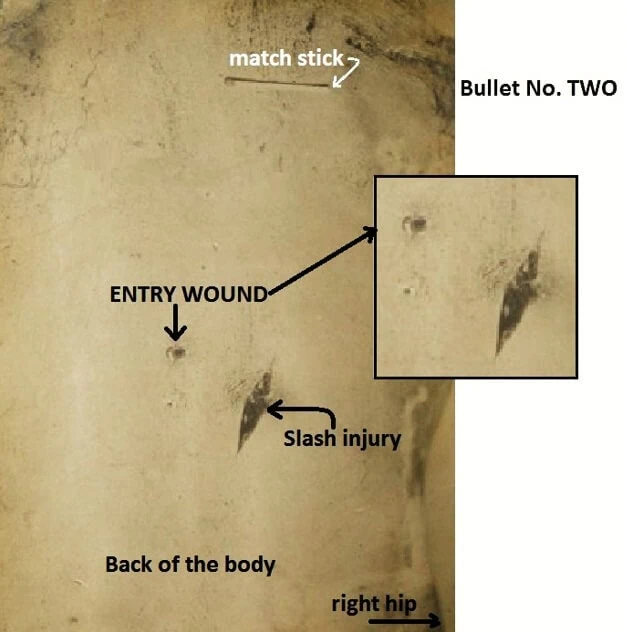

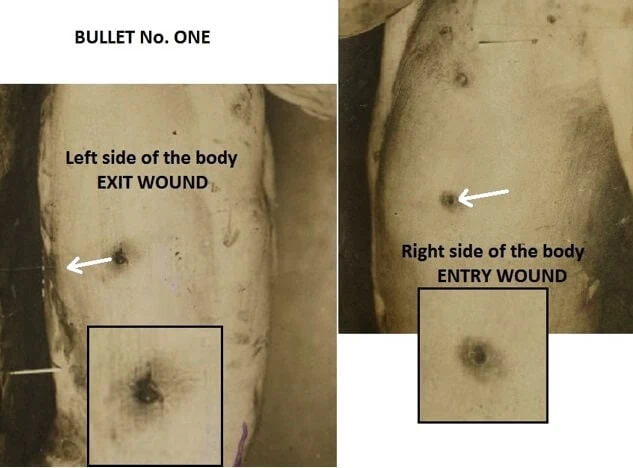

The autopsy confirmed her doubts. It found no trace of poison or drowning. Instead, Rasputin had died from a gunshot wound to the head. He had also suffered other wounds and blunt trauma, but the idea that he survived poison, multiple bullets, and drowning was a myth.

The tale, historians believe, was Yusupov’s invention. By portraying Rasputin as a near-demonic figure who refused to die, Yusupov cast himself as the heroic slayer of evil. It made for good theatre, if not good history.

The Aftermath

The conspirators expected Rasputin’s death to restore the monarchy’s prestige. Instead, it came too late.

Rasputin had written a prophetic letter to Nicholas, warning:

“If I am killed by common men, you and your family will rule for centuries. But if I am killed by nobles, the monarchy will fall, and your family will be killed by the Russian people.”

Police autopsy pictures of the murdered Rasputin.

Three months later, the February Revolution forced Nicholas II to abdicate. The Bolsheviks soon seized power. In 1918, Nicholas, Alexandra, and their children were executed.

Far from saving the dynasty, Rasputin’s murder symbolised its final collapse.

What Became of the Conspirators

Felix Yusupov fled into exile in Paris after the revolution. He lived until 1967, publishing memoirs that kept his lurid version of events alive.

Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich was also exiled and eventually moved to Paris, where he married an American heiress.

Vladimir Purishkevich remained in Russia but died of typhus in 1920 during the civil war.

Rasputin in Culture

Rasputin’s bizarre death entered popular imagination almost instantly. Soviet propaganda used him as a symbol of imperial corruption. Western writers and filmmakers transformed him into a demonic figure.

In the 1930s, Hollywood portrayed him as a sinister hypnotist in Rasputin and the Empress. Hammer Horror produced Rasputin: The Mad Monk in 1966. And in 1978, the German disco group Boney M. immortalised him in song: “Ra-Ra-Rasputin, lover of the Russian queen.”

Today, Rasputin’s story lives on in memes, video games, and endless retellings. Few figures have had such a strange journey from history into pop culture.

Autopsy images of Rasputin

The Mad Monk’s Legacy

Grigori Rasputin was many things: peasant, pilgrim, healer, drunk, womaniser, mystic, fraud, and confidant to an empress. His influence helped destabilise the monarchy, and his murder — whether by poison, bullets, or myth — foreshadowed the empire’s collapse.

His legend, inflated by those who killed him, has outlasted the monarchy itself. More than a century later, Rasputin remains both man and myth: a reminder of how history can turn flesh-and-blood figures into immortal stories.

Sources

Fuhrmann, Joseph T. Rasputin: The Untold Story. Wiley, 2013.

Radzinsky, Edvard. The Rasputin File. Doubleday, 2000.

Smith, Douglas. Rasputin: Faith, Power, and the Twilight of the Romanovs. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2016.

Yusupov, Felix. Lost Splendor: The Amazing Memoirs of the Man Who Killed Rasputin. Dial Press, 1953.

Rasputin, Maria. Rasputin: The Man Behind the Myth. Sidgwick & Jackson, 1977.

“Autopsy Report on Rasputin (1916).” Russian State Historical Archive.

Rappaport, Helen. The Romanov Sisters: The Lost Lives of the Daughters of Nicholas and Alexandra. Macmillan, 2014.

Britannica – “Rasputin” – https://www.britannica.com/biography/Rasputin

History.com – “Rasputin Assassinated” – https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/rasputin-assassinated

BBC – “Who Was Rasputin?” – https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-37324707

Comments