The Battle of Hayes Pond: How the Lumbee People Drove the Ku Klux Klan from Robeson County

- Jun 15, 2025

- 5 min read

On a cold January evening in 1958, an open cornfield near a quiet pond in Robeson County, North Carolina, became the unlikely stage for one of the most remarkable local acts of defiance against the Ku Klux Klan in American history. Known variously as the Battle of Hayes Pond, the Battle of Maxton Field or simply the Maxton Riot, this clash did not spring from any grandly orchestrated civil rights campaign but from a fiercely local resolve by the Lumbee people to defend their community against racial intimidation.

A Community at a Crossroads

By the mid-twentieth century, Robeson County was a rare example in the American South of an area with a large Native American population alongside sizeable white and black communities. The Native residents—later known as the Lumbee Tribe—descended from various Indigenous groups that had survived colonial conflict, disease, and centuries of encroachment by forging a new, distinct community around the Lumber River. By the 1950s, the Lumbees had formal recognition at the state and partial federal levels but, like black Americans, still faced entrenched discrimination in a segregated South.

While they generally shared many cultural traits with their white neighbours—speaking English, practising Protestant Christianity and largely working as farmers or labourers—segregation laws still classified them ambiguously as neither white nor black, creating a so-called ‘triracial’ county unique in the region. This ambiguous identity did not shield them from racial hostility, and the tensions simmered under the surface.

The Rise of Catfish Cole and the Klan’s Threat

In the wake of the Supreme Court’s 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision, which struck down segregated schooling, the Ku Klux Klan found new purpose among segregationists fearful of integration’s advance. Into this atmosphere stepped James W. “Catfish” Cole—a former marine and self-styled “Grand Wizard”—who founded the North Carolina Knights of the KKK and sought to swell its ranks by stoking racial fears.

In late 1957 and early 1958, Cole’s band of Klansmen targeted the Lumbee community specifically. They burned crosses near the homes of Native families accused of “race mixing” and publicly promised to hold a major rally near Pembroke, the heart of the Lumbee settlement. Local law enforcement, aware of the potential for violence, implored Cole to cancel. He refused, boasting he would show the sheriff “how to handle his people.”

Gathering at Hayes Pond

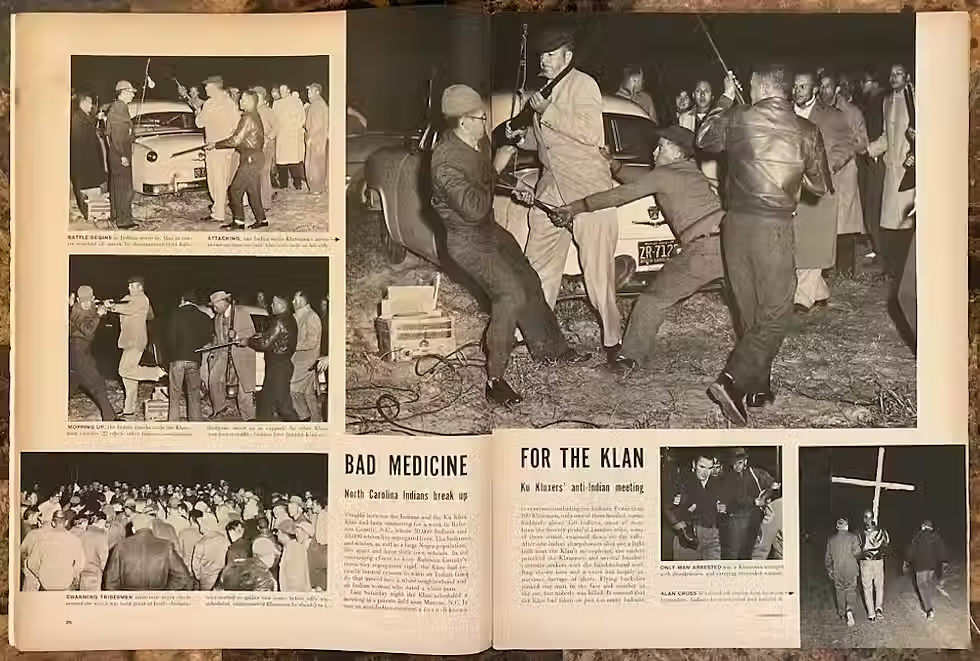

On 18 January 1958, Cole and around fifty Klan supporters—most from South Carolina, not locals—gathered on a cornfield beside Hayes Pond near the small town of Maxton. They erected a single floodlight, a crude sound system and the inevitable wooden cross for burning. News reporters and photographers from across the state turned up, sensing an explosive scene in the making.

Meanwhile, word had spread quickly through Lumbee families, barber shops and veterans’ halls. Many remembered how during the Second World War, Lumbee men had served with distinction alongside white soldiers. They returned home unwilling to tolerate racial intimidation on their doorsteps. Small groups of men, some armed with rifles and shotguns, gathered discreetly, waiting for darkness to fall.

By dusk, several hundred Lumbee men—estimates range from 300 to more than 500—had parked their cars along the surrounding roadways. Many brought wives and children, though the women mostly stayed in the vehicles, and many carried weapons in full view.

A Field Plunged into Darkness

Shortly before the Klan’s rally was to begin, the Lumbee made their move. Two local men, Neill Lowery and Sanford Locklear, stepped forward under the harsh floodlight. According to some, Locklear pointed his rifle at Cole and warned him there would be no speech that night. Then Lowery shot out the light.

Suddenly, the field fell dark. Some Lumbees fired into the air, others at the tyres of Klan cars, and a few shots whizzed into the woods. Chaos ensued. Klansmen scattered—some sprinting towards the nearest road, others crashing cars into ditches or hiding in the swampy brush. Cole himself abandoned his wife and children in his panic, disappearing into the wetlands until the next day.

Sheriff Malcolm McLeod and a handful of deputies fired tear gas to disperse the crowd, but the Lumbee had already won. As one onlooker later quipped, it was the shortest Klan rally ever held in North Carolina.

Triumph and Celebration

In the immediate aftermath, Lumbee men gleefully claimed Klan banners, the speaker system, and even the unburnt cross. That night, they paraded through the nearby town of Pembroke, hoisting their trophies and hanging an effigy of Catfish Cole for good measure.

Local and national press jumped on the story. Photographs of grinning Lumbee men wrapping themselves in captured Klan regalia appeared in papers across the country and even on the pages of Life magazine. In an era when violent Klan terror often went unchecked, the spectacle of Native Americans chasing armed Klansmen into a swamp proved irresistible to reporters and readers alike.

North Carolina’s governor and even other southern politicians praised the Lumbees’ firm stand. Alabama’s Governor Jim Folsom wryly remarked that he was glad to see “the Indian beat the paleface for once.” The Anti-Defamation League later said the story “sent a ripple of laughter clear across the country.”

The Klan’s Retreat and Decline

After the debacle, Catfish Cole was indicted for inciting a riot. So too was his drunken sergeant-at-arms, found in a ditch by the sheriff’s men. Cole swore he would return with an even bigger rally—this time with thousands of Klansmen. It never materialised. Instead, Cole’s influence waned, internal disputes fractured his North Carolina Knights, and state authorities increased pressure on Klan organising. By 1959, Cole was imprisoned on unrelated charges. He never again attempted a rally in Robeson County.

Remembering Hayes Pond

For the Lumbee people, the Battle of Hayes Pond became an enduring symbol of local self-reliance. While many national civil rights events drew leaders, lawsuits and federal intervention, this was a spontaneous defence by neighbours who knew one another by name. It remains a proud reminder that sometimes a community’s collective will is enough to see off those who threaten it.

In the decades since, the Lumbee have commemorated the night when their parents and grandparents drove the Klan from their fields. Songs have been written, books published and in 2018, a highway marker was installed near the site. Each January, Lumbee elders gather at Hayes Pond to tell the younger generations how their people once stood firm and forced the Klan to flee.

In the words of Lumbee Tribal Chairman Harvey Godwin Jr. at one such commemoration: “We drove the KKK out of Robeson County and they have never come back since. We need to use that energy to fight our battles today—without the weapons.”

Sources

Oakley, Christopher A. The Legend of Henry Berry Lowry: Strike at the Wind and the Lumbee Indians of Robeson County. The North Carolina Historical Review.

Lowery, Malinda Maynor. Lumbee Indians in the Jim Crow South. University of North Carolina Press.

Life Magazine archives (1958 spread on the Maxton Riot)

North Carolina State Archives: Governor Luther Hodges Papers

The Robesonian, various issues, January 1958

Associated Press archives

Comments