Shackleton and the Endurance Expedition: The Imperial Trans Antarctic Journey That Became a Fight for Survival

- Daniel Holland

- Feb 15, 2021

- 12 min read

“For scientific discovery give me Scott; for speed and efficiency of travel give me Amundsen; but when disaster strikes and all hope is gone, get down on your knees and pray for Shackleton.”

- Sir Raymond Priestly, Antarctic Explorer and Geologist.

It usually begins with an image. A photograph of a wooden ship tilted slightly in a sea of broken ice, its rigging taut against a pale Antarctic sky. A small figure stands nearby, dwarfed by the world around him. The ship looks both sturdy and impossibly fragile. The man looks purposeful, but also very small and very human. The ship is Endurance. The man is Ernest Shackleton. And the story is one of the most quietly remarkable sagas of survival ever recorded.

People sometimes imagine the Imperial Trans Antarctic Expedition as a bold geographical triumph because it sits so comfortably alongside Amundsen’s South Pole victory and Scott’s stoic final march. Yet Shackleton’s expedition achieved none of its original geographical goals. There was no crossing of the Antarctic continent. There was no meeting of the Weddell Sea and Ross Sea parties. Instead, the expedition became a different kind of milestone. It became a demonstration of practical resilience, improvisation, companionship, and the day by day work of staying alive.

The last breaths of the Heroic Age

To understand how the expedition came to be, it helps to understand the mood of polar exploration in the early twentieth century. The so called Heroic Age of Antarctic exploration had begun in the 1890s, driven by scientific curiosity, national prestige, personal ambition, and the chance to fill empty spaces on maps. Expeditions by men like Carsten Borchgrevink, William Speirs Bruce, Otto Nordenskjöld, Robert Falcon Scott and Roald Amundsen pushed deeper and deeper into the Antarctic interior. By 1912 the South Pole had been reached. Scott’s tragic death returning from the Pole had moved the British public deeply. Amundsen’s victory had set a new standard of efficiency. Mawson’s ordeal in East Antarctica had shown the landscape’s danger. And through it all Shackleton had become one of the era’s defining figures.

Shackleton’s 1907 to 1909 Nimrod expedition had taken him and his men further south than anyone before. He turned back 97 miles from the Pole, reasoning that to go on would risk his men’s lives. He wrote later with mild humour, “Better a live donkey than a dead lion.” Yet that expedition made him famous. His blend of courage and care for his men earned widespread admiration. His lectures filled halls. His name became familiar in both adventure writing and popular journalism.

But fame sits uneasily on a man who prefers activity to celebration. By 1912, Shackleton was increasingly restless. Friends noticed that he struggled to settle into ordinary civilian life. He had several business ventures, none entirely successful. He was good at inspiring men and far less good at sitting still. If the South Pole was gone, he wanted something else. A transcontinental crossing of Antarctica seemed the logical next step. He described it as “the one great main object of Antarctic journeyings”.

Planning an expedition in a changing world

Shackleton began planning long before he had the money. Fundraising was always an awkward task for him. He disliked the idea of appealing to the public. Instead, he sought wealthy patrons, government support and corporate partnership. The British government offered ten thousand pounds on the condition that he could raise the same amount privately. Slowly, contributions appeared. The industrialist James Key Caird gave twenty four thousand pounds. Dudley Docker offered ten thousand. Janet Stancomb Wills provided a generous sum.

With money in hand, Shackleton purchased two ships. The primary vessel was a Norwegian built barquentine originally named Polaris. Shackleton bought her for fourteen thousand pounds and renamed her Endurance, after the family motto “By endurance we conquer”. It was a name that would prove prophetically apt. He also purchased Aurora, a ship previously used by Douglas Mawson, to serve the Ross Sea party.

The plan was split between two teams. The Weddell Sea party, led by Shackleton, would land near Vahsel Bay and make the transcontinental march via the Pole. The Ross Sea party would land in McMurdo Sound, set up a base and lay supply depots across the Ross Ice Shelf and up the Beardmore Glacier. The depots were essential. Without them, the crossing party would not have enough food or fuel to survive the journey. The coordination required between the two teams and two oceans was complex. Yet Shackleton believed it could be done.

Recruiting the men

The recruitment process has become legendary, thanks to a widely repeated story that Shackleton placed an advertisement reading: “Men wanted for hazardous journey. Low wages, bitter cold, safe return doubtful.” While no original advert has ever been found, the story reflects the tone of the venture. Men from across Britain, Ireland, Australia and New Zealand applied. More than five thousand applications were received. Some applicants had polar experience. Others simply dreamed of adventure.

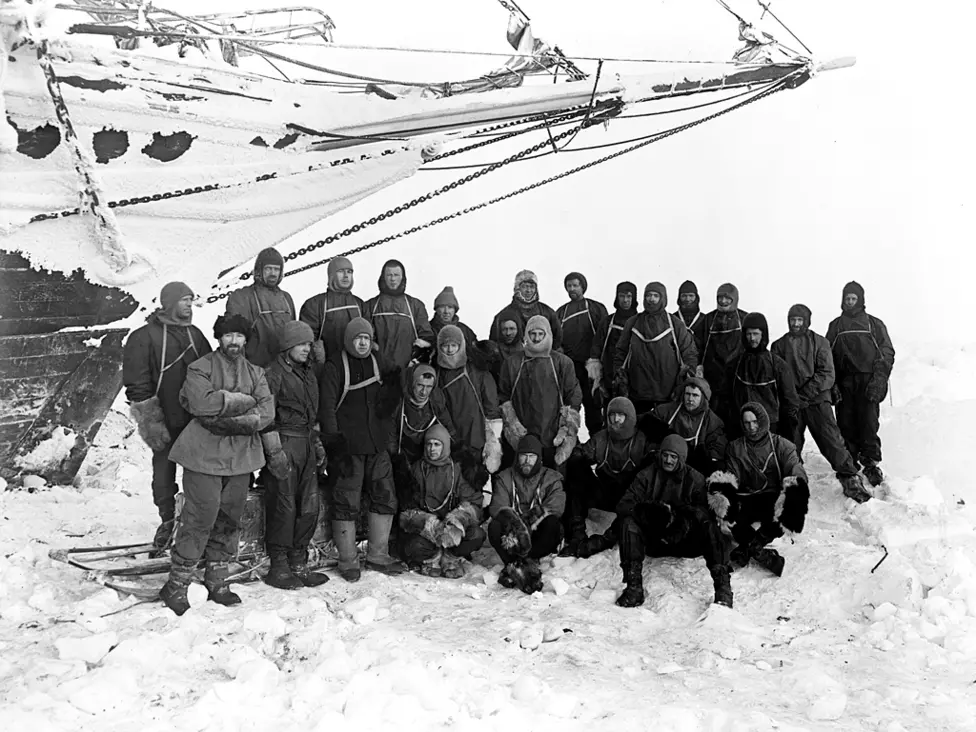

Shackleton selected a mixture of experienced hands and sturdy personalities. Frank Wild, his trusted second in command, had been with him on two earlier expeditions. Frank Worsley, a skilled navigator from New Zealand, became captain. Tom Crean, the quietly heroic Irish seaman from Scott’s expeditions, joined as second officer. There were scientists, engineers, carpenters, cooks, sailors and a pair of surgeons.

Frank Hurley, the Australian photographer known for his striking images, joined later in Buenos Aires. His photographs would go on to define much of how the world visualised the expedition. Hurley had a talent for capturing the deep calm of Antarctic light, the relationships between men and dogs, and the surreal geometry of pressure ridges.

Photographer Frank Hurley. (left) Third Officer Alfred Cheetham adjusts the signal flags of the Endurance.

Others joined through chance. William Bakewell signed on in Argentina. His friend, Perce Blackborow, was too young and inexperience to be accepted, so he hid aboard the ship as a stowaway. Shackleton discovered him only after Endurance had sailed. Far from being angered, Shackleton assigned him useful duties. Blackborow would later become one of the most notable survivors of Elephant Island, despite suffering severe frostbite.

Sailing into the Weddell Sea

Endurance left South Georgia on 5 December 1914. Experienced whalers warned Shackleton that the ice lay unusually far north that year. Shackleton listened but pushed on. His goal was Vahsel Bay, and the season was ticking. Within two days the ship encountered pack ice. Navigating through it was like threading a needle. The leads of open water were narrow and unpredictable. Sometimes the ship made steady progress. Sometimes she crawled. Sometimes she halted entirely. Men used long poles to push aside smaller floes and chisels to widen passages.

By mid January 1915 the ship was within sight of the continent. They spotted possible landing sites. They passed the location where Wilhelm Filchner had attempted to establish a base two years earlier. Shackleton chose not to land prematurely. He wanted to reach Vahsel Bay, the ideal starting point.

On 18 January the ice closed around Endurance. The grip felt firm but temporary. Shackleton hoped for a shift in the pack. He expected that the ice would loosen come spring. But the ice did not loosen. Instead, it tightened. The ship drifted with the pack. The men found themselves living aboard a vessel trapped in ice, hundreds of miles from open water.

Shackleton accepted the situation sooner than he admitted to the men. He converted the ship into a winter station. Dogs were housed in snow kennels. Scientists set up observational routines. The crew settled into life in a ship that was no longer a ship, but a wooden island drifting in silence.

Life in a frozen world

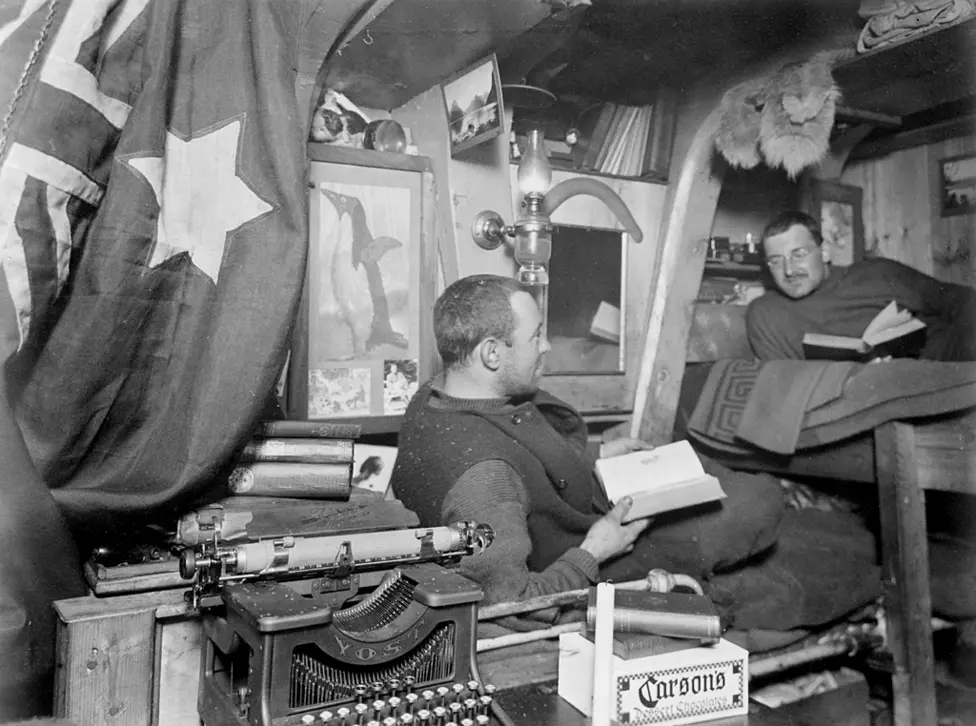

The long Antarctic winter created a strange mix of monotony and tension. Days passed slowly. The temperature fell. The sunlight dimmed and finally vanished. Men marked time by meals, dog feeding, scientific observations and small rituals designed to keep the mind steady. Leonard Hussey’s banjo became a cultural anchor. Hurley held occasional shows of his photographs. They read books, wrote letters, and took walks on the ice when the weather allowed.

At first the drift was slow. By April the ship had moved only a small distance north. But the character of the ice was changing. Pressure ridges formed. Cracks groaned in the night. The ship’s timbers creaked under the strain. On some days great blocks of ice rose out of the sea, pushed up by forces the men could feel but not see. Shackleton compared them to stones squeezed between finger and thumb.

As the months passed the situation went from discomfort to danger. The ice floes shifted unpredictably. On several occasions the pressure was so intense that the ship twisted and shuddered. The men heard loud reports, like distant gunfire, as timber gave way. The ship began taking on water. The carpenter, McNish, attempted structural reinforcement but it was not enough.

On 27 October 1915 Shackleton gave the order to abandon ship. Men hauled stores, tents, sledges, and the three lifeboats onto the ice. Hurley went back into the damaged hull to salvage his photographic plates. He chose about one hundred and smashed the rest. His diary mentions the bittersweet feeling of destroying work he loved.

Three weeks later, on 21 November, Endurance slipped beneath the ice.

Ocean Camp and the march that failed

The men established Ocean Camp on a stable floe. Shackleton believed initially that they could march to Paulet Island, where they knew a food depot existed from earlier expeditions. The distance was considerable but not impossible. They loaded sledges with tents, food, cooking equipment and one of the lifeboats.

The march lasted only a few days. The ice was too chaotic. Pressure ridges made progress agonisingly slow. Men sank to their knees. The sledges stuck. The floes moved unpredictably beneath them. Shackleton halted the march and returned to Ocean Camp.

Food became central to every decision. Seal meat and penguin meat supplemented the tinned provisions. The dogs, once valued companions, required more food than the men could spare. Shackleton ordered them shot. This was one of the hardest moments of the entire journey. Men wept openly. Hurley wrote in his diary that the silence after the dogs were killed felt heavier than any storm.

Patience Camp: waiting for the ice to break

By late December Shackleton attempted a second march. It failed for the same reasons as the first. After seven days they had marched for only a handful of miles. Shackleton gathered the men and said plainly: “It would take us over three hundred days to reach land.”

The men established a long term camp which they named Patience Camp. Its name was apt. They waited while the floe drifted. They watched distant mountains pass. They monitored cracks. They hunted seals when possible. They repaired equipment. They rationed food. The cold pressed through their clothes. Men gave up unnecessary conversation. They slept, woke, ate and waited.

By March 1916 the floe had drifted near the latitude of Elephant Island, but still too far east to reach it by foot. Shackleton’s plan became clear: when the floe finally broke, they would launch the lifeboats and try to reach one of the islands by sea.

The break came on 8 April. The floe split suddenly. The men scrambled to load the boats. The sea ahead was a fractured landscape of ice and water. They launched the three lifeboats on 9 April and began one of the most difficult journeys of the entire saga.

The boat journey to Elephant Island

The three boats battled through drift ice. They camped on floes when possible, only to wake and find their temporary shelters breaking apart. Temperatures fell. Spray turned to ice. Frost formed on beards and clothes. Men bailed constantly. The strain was physical and mental.

Shackleton considered several potential destinations. At first he aimed for Hope Bay. Then Deception Island. But as men weakened, as frostbite set in, as weather worsened, he focused on the nearest land: Elephant Island.

On 14 April they sighted the south east coast. It offered no safe landing. Vertical cliffs met the sea. The next day they reached a narrow beach. The sand felt strange under their feet after so long on ice. Wild later found a better location seven miles west. They moved there and established a more secure camp.

It was the first solid land they had stood on in nearly a year and a half.

Elephant Island and the necessity of the James Caird voyage

Elephant Island had no whaling stations. No shipping routes. No possibility of random rescue. Shackleton knew this. If the men were to survive, he had to fetch help. He selected the James Caird, the strongest of the boats.

McNish rebuilt it. He raised the sides, added a deck made from canvas and wood, reinforced the keel, and adapted the craft for long ocean travel. How he managed this with minimal tools remains remarkable.

Shackleton chose five companions: Worsley, Crean, McNish, Vincent and McCarthy. Wild would command the twenty two men remaining behind. Hurley helped photograph the departure. The James Caird launched on 24 April 1916.

The 800 mile crossing to South Georgia

The voyage took fourteen days. It crossed the stormiest waters on Earth. The boat was continually soaked. Ice built up on deck. Worsley’s navigation depended on the rare moments when clouds thinned enough to reveal the sun. Shackleton described waves rising higher than buildings.

One night the rudder froze. Another night Vincent collapsed. There were days when the boat was tossed so hard that bailing became a continuous necessity. They slept in shifts, curled against each other for warmth.

On 8 May South Georgia appeared through a break in the weather. They landed on 10 May at King Haakon Bay.

The interior crossing of South Georgia

Vincent and McNish were too weak to travel. Shackleton, Worsley and Crean set off on foot on 19 May. They had no map. They guessed the route. They crossed mountains and valleys. They stumbled through snowfields and nearly invisible crevasses. At one point they slid down a snowy slope, guided only by instinct.

After thirty six hours of continuous travel they heard the whistle of the whaling station at Stromness. Their ordeal was nearly over.

The station manager Simon McDonald wrote years later that the three men looked “more like a handful of scarecrows than anything else”. Their faces were blackened by smoke and salt. Their clothing was patched. Their beards were full of ice.

Four rescue attempts

Shackleton rescued the three men left with the James Caird, then made plans to rescue the men on Elephant Island. The first three attempts failed due to ice. A fourth attempt, using the Chilean tug Yelcho, succeeded. Captain Luis Pardo steered through difficult waters. Fog lifted at the right moment. The camp was sighted. The men were rescued on 30 August 1916.

Not one life from Shackleton’s party was lost.

Life on Elephant Island

While Shackleton journeyed for help, the men on Elephant Island endured a winter in a shelter built from two overturned boats. They called it the Snuggery. The interior smelled of smoke, damp clothes and penguin fat. The ceiling was low. Men could not stand upright. They cooked on a blubber stove that covered everything with soot.

Wild was endlessly calm. He kept routines. He told stories. He organised hunting. When asked how soon Shackleton would return, he replied most mornings, “Pack your things, boys. Boss may come today.” His optimism helped hold the men together.

Blackborow’s frostbite worsened. The surgeons amputated his toes in candlelight. The operation took about fifty five minutes. They had only a small amount of chloroform left. The procedure was successful.

As winter deepened, the men grew quiet. They slept often. They ate simply. They told stories to pass the time. The blubber stove hissed and smoked. When Shackleton finally arrived, some men initially believed they were hallucinating.

The Ross Sea party: a quieter but equally heroic tragedy

On the opposite side of Antarctica the Ross Sea party faced its own ordeal. They had arrived late. They began depot laying prematurely. Then Aurora was blown out to sea in a storm and drifted for nearly ten months. This left the men without proper clothing, fuel or equipment.

They salvaged what they could from Scott’s old hut at Cape Evans. They laid depots faithfully, despite growing illness. Several men developed scurvy. Spencer Smith died. Later Mackintosh and Hayward disappeared while crossing unstable ice.

When Aurora returned in January 1917, only seven survivors remained. Their efforts, though overshadowed in popular history, were essential to the expedition’s original plan.

The return home, the war and the last chapter of Shackleton’s life

When the expedition returned, Europe was in the midst of the First World War. Many members enlisted immediately. Some were killed. Others were wounded.

Shackleton undertook wartime administrative work in northern Russia. He later planned one final Antarctic expedition aboard Quest and brought several Endurance veterans with him. He died suddenly in South Georgia in January 1922. His men buried him there, facing the sea.

On 27 November 2011, the ashes of Frank Wild were interred on the right-hand side of Shackleton's gravesite in Grytviken. The inscription on the rough-hewn granite block set to mark the spot reads: "Frank Wild 1873–1939, Shackleton's right-hand man."

Sources

• “Endurance22: The Discovery of Shackleton’s Lost Ship”

Endurance22 Official Expedition Site

• “Shackleton’s Endurance Found in Antarctic Depths”

National Geographic

https://www.nationalgeographic.com/history/article/explorers-found-lost-ship-shackleton-endurance

• “Endurance: The Extraordinary Discovery of Shackleton’s Shipwreck”

National Geographic Documentary Films

• “Centenary of Shackleton’s Antarctic Rescue by the Chilean Navy”

Navy History Australia

https://navyhistory.au/centenary-of-shackletons-antarctic-rescue-by-the-chilean-navy

• “Shackleton and the Endurance: Expedition Overview and Crew Accounts”

CoolAntarctica

• “South: Shackleton’s Own Narrative of the Ross Sea Party”

CoolAntarctica (Full text chapters)

https://www.coolantarctica.com/Antarctica%20fact%20file/History/south/south_shackleton_chapter13.php

• “Ross Sea Party: Hut Point and Survival on the Ice”

New Zealand Antarctic Heritage Trust

https://nzaht.org/conserve/famous-discoveries/ross-sea-party-tent/