Spandau Prison: The Fortress of Forgotten Tyrants

- Jun 11, 2025

- 9 min read

Updated: Aug 17, 2025

In the Berlin district of Spandau, a red-brick compound once loomed behind layers of concrete walls, barbed wire, and armed watchtowers. Constructed in 1876 during the German Empire, the prison’s quiet beginnings as a military detention centre would give way, over the following century, to a darker renown. By the mid-20th century, Spandau Prison had transformed into one of the most symbolically charged sites in Europe, detaining the surviving elite of Hitler’s regime. It was guarded not just by soldiers, but by history itself.

Its final chapter—demolition in 1987 following the death of Rudolf Hess, its last and most enigmatic inmate—was undertaken with calculated intent: to prevent the location from ever becoming a monument to neo-Nazi nostalgia. The materials were obliterated, the ground repurposed, and the past deliberately buried.

Origins Under the German Empire

Spandau Prison was originally built in 1876 on Wilhelmstraße to serve as a military prison for the Prussian Army. Its original design reflected the philosophy of regimented discipline typical of late 19th-century penal architecture—functional rather than reformative. High walls, narrow cells, and austere corridors provided a controlled environment for hundreds of military detainees. Following Germany’s defeat in World War I and the fall of the monarchy in 1918, the prison was repurposed to also house civilian inmates. By the early Weimar Republic years, Spandau could accommodate up to 600 individuals and had become a standard, albeit high-security, penitentiary within the German justice system.

Nazi Era: From Custody to Proto-Concentration Camp

The Reichstag fire in February 1933 marked a sharp turn in German political life. As Adolf Hitler used the event to justify the suspension of civil liberties and the arrest of political opponents, Spandau was swept into this authoritarian surge. The prison became one of the earliest instruments of Nazi political repression. Though not officially categorised as a concentration camp, it began to function in a comparable way. It was one of the first places where individuals were detained under “Schutzhaft” (protective custody), a Nazi legal invention that required no charges or trial.

Among the early detainees were Egon Kisch, the Jewish-Czech journalist, and Carl von Ossietzky, a pacifist publicist and later Nobel Peace Prize laureate. Kisch would later recall the brutal beatings and psychological torment meted out by Gestapo officials who operated with impunity inside the facility, despite the fact that the prison nominally remained under the authority of the Prussian Ministry of Justice.

By late 1933, the Nazis were constructing purpose-built concentration camps across Germany and Austria. Dachau, Oranienburg, Lichtenburg, and Esterwegen opened in rapid succession. With the new infrastructure in place, those held in protective custody at Spandau were largely transferred out, and the prison reverted to regular use for conventional criminal sentences during the remainder of the Nazi period.

The Post-War Reckoning: Nuremberg to Spandau

After the defeat of Nazi Germany in 1945, Spandau Prison found itself in the British-administered sector of a divided Berlin. While the wider administration of Germany passed to the Allied Control Council, Berlin’s four sectors were jointly administered by the Four Powers: the United Kingdom, the United States, France, and the Soviet Union. It was under this collective jurisdiction that Spandau was selected to house those senior Nazis who had been sentenced to terms of imprisonment at the Nuremberg Trials in 1946.

Despite initial expectations that the prison might house over a hundred war criminals, only seven men were ultimately incarcerated there:

Rudolf Hess – Hitler’s deputy and the only inmate to serve a life sentence in full. He became the sole remaining prisoner for over two decades.

Albert Speer – Hitler’s chief architect and Minister of Armaments. Released in 1966 after completing a 20-year sentence.

Baldur von Schirach – Head of the Hitler Youth and Gauleiter of Vienna. Served a 20-year sentence; released on 30 September 1966.

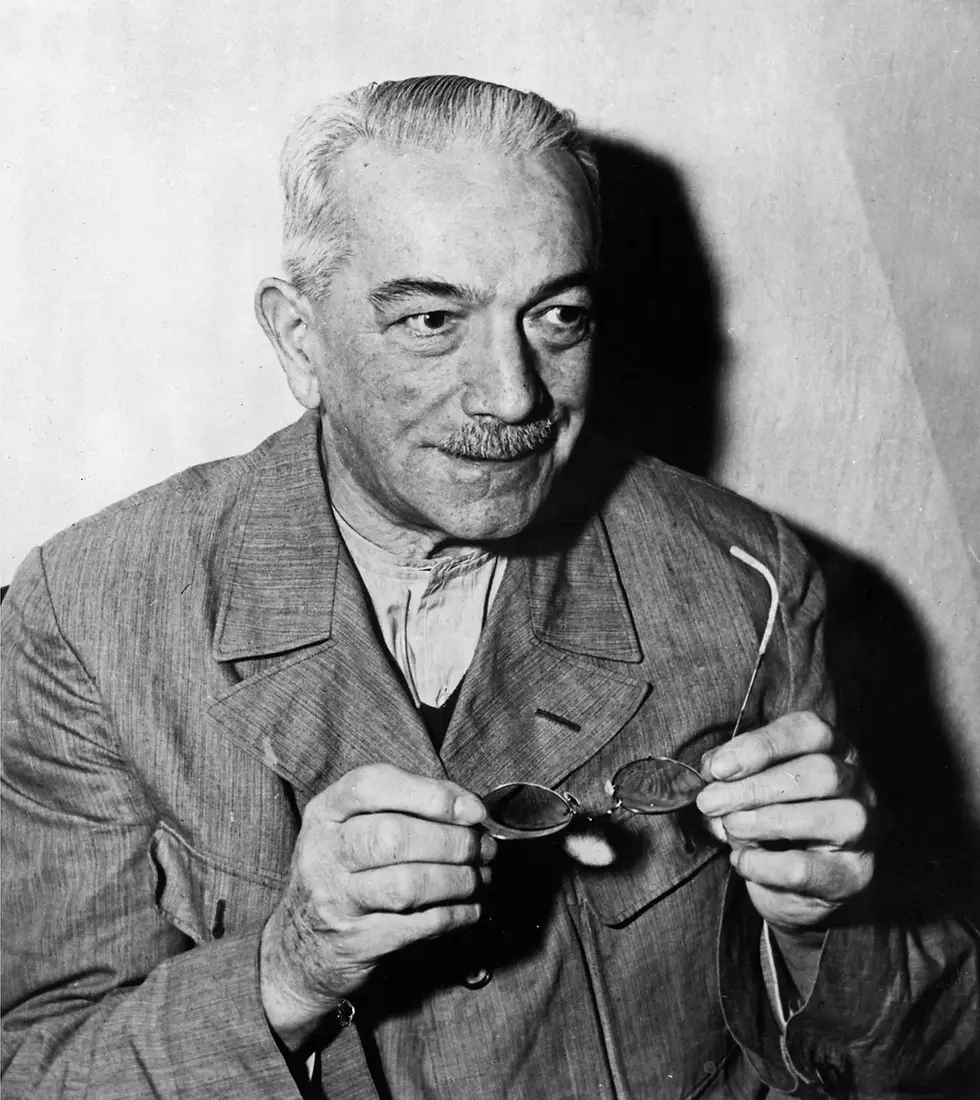

Karl Dönitz (Centre in dark coat)– Admiral of the Kriegsmarine and briefly Hitler’s successor. Released in 1956 after 10 years.

Erich Raeder – Grand Admiral of the Navy. Sentenced to life but released in 1955 due to ill health.

Walther Funk – Economic minister and Reichsbank president. Also sentenced to life but released in 1957 due to poor health.

They arrived on 18 July 1947 and remained the only inmates the prison would ever accommodate under the Four-Power administration.

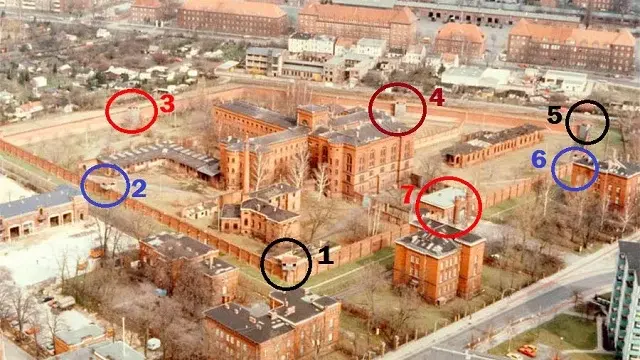

The Structure and Security of the Prison

By modern standards, Spandau was both overbuilt and underused. The facility itself featured a high-security perimeter with successive layers: a 4.5-metre wall, a 9-metre wall, a third electrified barrier topped with razor wire, and another external barbed-wire fence. Six machine gun-equipped guard towers were manned 24 hours a day by an international military contingent. There were approximately sixty soldiers on site at any time, rotating duties according to the nationality in charge that month.

The cells were roughly 3 metres long by 2.7 metres wide and 4 metres high. For the seven inmates, alternate cells were deliberately kept empty to prevent Morse code communication. Spare cells were converted for auxiliary use: one became a chapel, another a library. The remaining cells often served practical purposes, such as tool storage or garden supplies.

Despite the enormous space and staffing, the prison was strictly regulated. Each country took control of the facility for one month at a time, rotating flags and administration. All operations—from dietary menus to visitation—were subject to the often competing interpretations of the Four Powers. The Western nations generally favoured more humane treatment. The Soviets, by contrast, insisted on rigid adherence to harsh conditions, reflecting their desire for maximum retribution.

A Prison of Spectacle and Symbolism

Each prisoner was subjected to exacting routines. Wake-up was at 6 a.m., followed by cleaning duties, breakfast, and time in the garden (weather permitting). After a midday meal and brief rest, they returned outside before supper at 5 p.m. Lights out was at 10 p.m. Monday was laundry day, and shaving or haircuts were allowed three times a week. This cycle varied little, except under the occasional modifications introduced by the power in charge.

Restrictions were initially severe: only one letter per month, 15-minute family visits every two months, a complete ban on newspapers, memoirs, and diaries. At night, guards would shine torches into cells every fifteen minutes to deter suicide. Over time, these measures were softened, largely due to Western protest, but the Soviets blocked many reforms, arguing that leniency would undermine the denazification effort.

This discrepancy meant that conditions could vary dramatically from month to month, depending on which nation held control. The inconsistency extended to meals, medical care, recreation, and disciplinary measures.

The Garden and Architect of Redemption

Perhaps the most curious feature of Spandau was its large garden, an ironic luxury given the prisoners’ infamy. Initially divided into individual allotments, the inmates grew vegetables and flowers. Dönitz preferred beans, Funk cultivated tomatoes, while Speer grew daisies. The produce was technically required to go to the prison kitchen, but often found its way to guards’ tables.

As the years passed and the other prisoners were released, Speer, an architect by training, transformed the garden into an elaborate network of paths, flowerbeds, and rock features. It became his principal occupation. When Speer and Schirach were released in 1966, leaving only Hess behind, the garden was abandoned.

Rudolf Hess: The Loneliest Man in the World

By 1966, Rudolf Hess stood alone inside Spandau’s cold confines. Hess, who had been sentenced to life at Nuremberg, was considered too unstable and dangerous to be released. Paranoid, hypochondriacal, and prone to long fits of moaning, Hess resisted work duties and often feigned illness. He would only eat food placed furthest from him on the table, believing others might be poisoned.

He refused visitors for more than 20 years. When he finally agreed to see his wife and son in 1969, it was a national event. As the lone inmate, Hess’s needs dominated the prison’s operations. He was moved from cell to cell nightly to prevent escape or suicide. Guards monitored him constantly, and visits to hospital involved an entire wing of the British Military Hospital being secured by the Royal Military Police and an infantry battalion.

His only regular human contact came from Eugene K. Bird, the American commandant of the prison, who eventually befriended Hess and later authored The Loneliest Man in the World, detailing their surreal relationship.

Internal Politics and Petty Feuds

Within the walls of Spandau, the old rivalries of Nazi Germany simmered on. Raeder and Dönitz, both grand admirals, resumed their feud about naval strategy. They even created embroidered insignia for themselves, Raeder as “Chief Librarian” with a silver book and Dönitz as “Assistant” with a gold one.

Speer was ostracised for admitting guilt at Nuremberg. Dönitz resented him, wrongly believing Speer had recommended him as Hitler’s successor. Schirach and Funk formed a tight friendship. Von Neurath, the elder diplomat, was liked by all. Reconciliation was rare and fleeting.

There were also more frivolous intrigues. Funk was somehow able to secure regular access to cognac, and special occasions were marked by quiet toasts. Prisoners created secret communication routes through sympathetic guards. Speer secretly wrote his memoirs, on toilet paper, which were smuggled out and later published as Inside the Third Reich.

Dissolution and Demolition

By the 1980s, many questioned the logic of maintaining an entire prison complex and garrison for one aged man. Yet political deadlock between East and West, and perhaps the Soviets’ desire to retain a presence in West Berlin, prevented reform.

Hess was found dead on 17 August 1987, aged 93, in a summer house that had been set up in the prison garden as a reading room; he had hanged himself using an extension cable strung over a window latch. A short note to his family was found in his pocket, thanking them for all that they had done. The Four-Power Authorities released a statement on 17 September ruling the death a suicide. Hess was initially buried at a secret location to avoid media attention or demonstrations by Nazi sympathisers, but his body was re-interred in a family plot at Wunsiedel on 17 March 1988; his wife was buried beside him in 1995.

Hess' lawyer Alfred Seidl felt that he was too old and frail to have managed to kill himself. Wolf Rüdiger Hess repeatedly claimed that his father had been murdered by the British Secret Intelligence Service to prevent him from revealing information about British misconduct during the war. According to an investigation by the British government in 1989, the available evidence did not back up the claim that Hess was murdered, and Solicitor General Sir Nicholas Lyell saw no grounds for further investigation. The autopsy results supported the conclusion that Hess had killed himself. A report declassified and published in 2012 led to questions again being asked as to whether Hess had been murdered. Historian Peter Padfield wrote that the suicide note found on the body appeared to have been written when Hess was hospitalised in 1969.

After Hess' death the Four Powers swiftly agreed to demolish the prison. Bulldozers reduced the structure to rubble. The bricks were pulverised and scattered into the North Sea or buried at RAF Gatow. A shopping centre, The Britannia Centre Spandau, was built on the site to serve British troops. It was jokingly nicknamed “Hessco’s,” a pun on the UK’s Tesco supermarket chain.

One set of keys survives, displayed at the King’s Own Scottish Borderers Museum in Berwick-upon-Tweed.

Cultural Footnotes

Spandau’s shadow extended even into pop culture. The British band Spandau Ballet took their name from graffiti in a Berlin nightclub lavatory. The phrase alluded to condemned men “dancing” at the end of a hangman’s rope, a morbid joke from the prison’s gallows era. Though Spandau saw no executions under Allied administration, the phrase endured as a symbol of state-inflicted death.

Sources

Spandau: The Secret Diaries – Wikipedia (Albert Speer’s memoir)

134 Cells, One Inmate: The Closure of Spandau Prison – ADST

Nazi war criminals in Spandau prison ‘could not sleep due to searchlights’ – The Guardian

Spandau Prison. A Soviet warder tells his story – spandau-prison.com

Book Sources

Norman J. W. Goda – Tales from Spandau: Nazi Criminals and the Cold War (Cambridge University Press, 2007)

https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/tales-from-spandau/89B4E76F553CA71E9ED23A5B6AB3B2FA

Albert Speer – Spandau: The Secret Diaries (Macmillan, 1976)

ISBN: 978-0-02-612610-4

Jack Fishman – Long Knives and Short Memories: The Spandau Prison Story (Breakwater Books, 1981)

ISBN: 978-0710007318

Comments