Recoil In Horror At The Story Of The Man Who Cut Out His Own Appendix

- Aug 25, 2019

- 4 min read

Most people get squeamish just thinking about an operation. Now picture being so far from civilisation that when your appendix starts acting up, the only person around with the skills to fix it is… you. This was the brutal reality for Leonid Rogozov, a young Soviet surgeon who, during an expedition to one of the most remote corners of Earth, found himself facing a choice no one wants: perform surgery on himself or almost certainly die.

Trouble in the Polar Wasteland

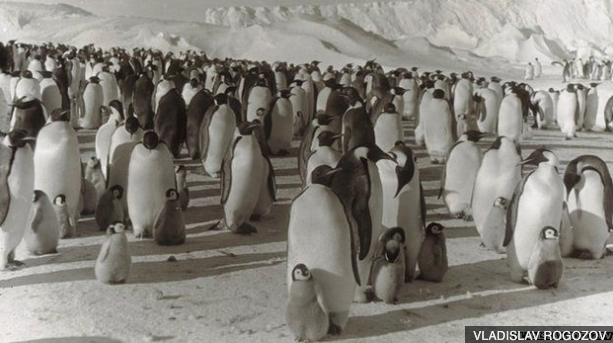

In 1961, Leonid Rogozov was just 27 and part of the Soviet Union’s sixth Antarctic expedition. His team of a dozen hardy souls had been tasked with setting up a brand-new base at the Schirmacher Oasis, which sounds a lot more inviting than it really was — a desolate stretch of frozen nothingness battered by gales and endless snow.

By mid-February that year, the Novolazarevskaya Station was up and running. The men settled in, ready to outlast the long Antarctic winter together. But by the time April rolled round, Leonid started feeling off: lethargy, nausea, and then a sharp pain stabbing his right side — the textbook signs of appendicitis.

Being the only doctor on site, he didn’t have the luxury of asking for a second opinion. His son Vladislav later put it plainly: “It’s a routine operation in the civilised world, but unfortunately, he didn’t find himself in the civilised world — instead he was in the middle of a polar wasteland.”

No Escape, No Help

For Rogozov, it must have felt like a nightmare in slow motion. He knew precisely what was happening inside his body — and what would happen if he did nothing. A burst appendix is not something you can just sleep off, especially not when your nearest hospital is across blizzards, pack ice, and several thousand miles of hostile ocean.

Calling for help was futile. The ship that had brought them down took 36 days by sea — it wouldn’t be back for a year. And as for planes, the howling storms ruled out any hope of a quick rescue. Rogozov’s life was now down to him alone.

The base commander needed permission from Moscow before green-lighting such an extreme measure — it was the Cold War, after all, and every mishap was political ammunition. If Rogozov failed, it would be an embarrassing dent in the image of Soviet heroism at the very height of the polar race.

But there was no other choice. So Rogozov decided to gamble on the impossible: a self-performed appendectomy.

“A Snowstorm Whipping Through My Soul”

Rogozov kept a diary throughout, his stoicism laid bare in dry, honest scribbles. On the night before his surgery he wrote, “It hurts like the devil! A snowstorm whipping through my soul, wailing like 100 jackals… I have to think through the only possible way out — to operate on myself… It’s almost impossible… but I can’t just fold my arms and give up.”

In those words, you glimpse a man torn between medical logic and raw fear — aware of the risk but compelled by a stubborn will to live.

Surgical Plans in the Freezing Dark

Never one to wing it, Rogozov devised a careful plan. He assigned two assistants — neither of whom had ever assisted in surgery before — to pass him instruments and hold a mirror and a lamp. He even coached them on emergency procedures: how to give him a jolt of adrenaline if he passed out, and how to ventilate him if he stopped breathing.

A general anaesthetic was out of the question — he couldn’t risk knocking himself out completely. So he injected his own belly wall with novocaine, steeled his nerves, and picked up the scalpel.

“My poor assistants! At the last minute I looked over at them. They stood there in their surgical whites, whiter than white themselves,” he wrote later. “I was scared too. But when I picked up the needle and gave myself the first injection, somehow I switched into operating mode.”

By Touch, Not Sight

The mirror idea didn’t last long. Trying to operate backwards through an inverted reflection was worse than working blind, so Rogozov did it by feel, probing and cutting his own flesh with bare hands. No gloves, no luxury of detachment — just him, his tools, and pain.

At one point, he accidentally nicked the blind gut and had to stitch it up mid-procedure. Blood was pouring, his head was spinning, and every few minutes he paused for 20 seconds just to keep from blacking out. “Finally here it is, the cursed appendage!” he scribbled. A black stain at its base meant he had been frighteningly close to a fatal rupture.

Two Hours, a New Lease on Life

After nearly two hours of agony and grit, Rogozov stitched himself back up. Before resting, he calmly told his team how to sterilise the tools and clean the room. Only then did he allow himself antibiotics and a few hours’ sleep.

Remarkably, he was back on light duty within a fortnight, tending to his comrades and keeping the station running.

Home at Last — and an Unwanted Fame

When the time came to leave Antarctica, the team faced more drama: a blockade of ice nearly trapped them for another year. They were eventually airlifted out in nail-biting conditions — one plane almost ditched into the ocean.

Back in the USSR, Rogozov returned a hero, his story plastered across Soviet papers as an example of the unbreakable young Soviet man — alongside cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin, who had rocketed into space just weeks before. Both men were 27, both working class, both symbols of the state’s unshakable strength.

Rogozov himself shunned the fuss. He quietly went back to his beloved hospital job the very next day.

A Lesson for Explorers and Astronauts Alike

Today, any Antarctic team from Australia or elsewhere must have their appendix out before heading south. Some experts have even floated the idea that future Mars colonists should do the same — just in case.

Rogozov’s son Vladislav puts it best: “If you find yourself in a desperate situation when all the odds are against you… believe in yourself and fight. Fight for life.”

Comments