Native Americans Acknowledged 5 Genders, And Then European Christians Showed Up.

- Jan 30, 2019

- 5 min read

Before European contact reshaped the continent and its many cultures, Native American societies offered a markedly different view of gender—one rooted not in binaries or conformity, but in spiritual fluidity and communal respect. Contrary to the rigid gender norms that would be imposed later, Indigenous communities throughout North America recognised, honoured, and even celebrated what we might today refer to as gender diversity.

Rather than forcing individuals into fixed male or female roles, Native societies accepted that gender could exist along a spectrum. The term “Two Spirit,” a modern pan-Indigenous phrase coined in 1990, attempts to encapsulate a wide variety of traditional understandings of people who embody both masculine and feminine traits. This concept is not new. It is rooted in centuries of cultural practices and spiritual beliefs in which gender-variant individuals played essential roles.

In fact people who had both female and male characteristics were viewed as gifted by nature, and therefore, able to see both sides of everything. According to Duane Brayboy, writing in Indian Country Today, all native communities acknowledged the following gender roles: “Female, Male, Two Spirit Female, Two Spirit Male and Transgendered.”

He goes on to describe how: “Each tribe has their own specific term, but there was a need for a universal term that the general population could understand. The Navajo refer to two spirits as nádleehí (one who is transformed); among the Lakota is winkté (indicative of a male who has a compulsion to behave as a female), niizh manidoowag (two spirit); in Ojibwe, hemaneh (half man, half woman), to name a few.”

A World Without Gender Roles

In many Native American societies, value was placed not on conformity to masculinity or femininity, but on a person’s contributions to the tribe. People were recognised for their skills, talents, wisdom, and spirit, not their adherence to gender expectations. Tasks were not strictly divided along gendered lines, and children were often raised without the imposition of gender-specific roles. Their clothing was typically gender-neutral, and their path in life—whether as a warrior, healer, cook, or leader—was guided by their calling rather than social prescription.

Gender identity and sexual orientation were largely considered private matters. There were no terms akin to “homosexual” or “transgender” in pre-contact Indigenous lexicons in the way Western societies define them today, though the experiences and roles these terms try to describe were recognised and respected in many Indigenous cultures.

The Reverence of Two Spirit People

People who embodied both male and female characteristics were not seen as anomalies or misfits. They were seen as spiritually gifted, often believed to possess the rare ability to perceive the world through dual lenses. According to Indian Country Today, all Native communities acknowledged a broad range of gender roles, including female, male, Two Spirit female, Two Spirit male, and transgender individuals.

Different tribes had distinct words and concepts for these people. For the Navajo, the word was Nádleehí, meaning “one who is transformed.” Among the Lakota, they were called Winkté, a term usually used for a male with a compulsion to behave as a female. The Ojibwe used Niizh Manidoowag—“two-spirited”—while in Cheyenne, the word was Hemaneh, or “half man, half woman.”

Though each term had its own specific cultural nuance, the Two Spirit identity often involved a ceremonial role. Two Spirit individuals frequently served as healers, visionaries, matchmakers, caretakers, or spiritual leaders. Some were medicine people; others performed in special rituals. Their capacity to balance male and female energies was seen as spiritually powerful, a trait that enriched the community rather than threatened it.

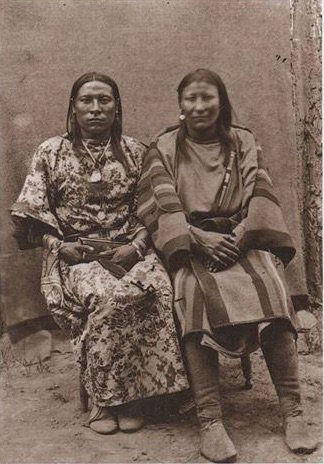

The Case of Osh-Tisch

One of the most documented Two Spirit individuals in historical record is Osh-Tisch, a member of the Crow Nation whose name translates as “Finds Them and Kills Them.” Born biologically male, Osh-Tisch lived as a woman and wore women’s clothing. In 1876, during the Battle of the Rosebud—a confrontation between Native forces and the US Army—Osh-Tisch distinguished herself by saving a fellow warrior. Despite facing the ongoing encroachment of colonial forces, she lived as herself, embodying the ancient traditions of her people.

Osh-Tisch married a woman and maintained her identity in a period when traditional roles were under immense pressure from outside forces. Her bravery in battle and visibility in society made her a symbol of the enduring role of Two Spirit people even in times of great cultural upheaval.

Colonial Erasure and Suppression

With the arrival of European colonists, particularly the English, French, and Spanish, these inclusive concepts of gender and sexuality were targeted for elimination. The imposition of Christianity—and its rigid dichotomies of man/woman, good/evil—brought with it an ideological drive to stamp out Indigenous beliefs.

Missionaries and colonial administrators viewed gender diversity as immoral, a threat to their cultural and religious order. The Spanish Catholic clergy, for example, destroyed most of the Aztec codices, obliterating Indigenous histories and cosmologies that included Two Spirit traditions. English and American colonists followed suit.

American painter and ethnographer George Catlin, known for his portraits of Native Americans, was particularly vocal about his belief that the Two Spirit tradition should be eradicated. He wrote that it “must be extinguished before it can be more fully recorded.” That ominous sentiment reflected a wider campaign of cultural genocide—not just through warfare and land seizure, but through the erasure of beliefs and traditions that conflicted with colonial norms.

As a result, many Two Spirit people were forced to live in secrecy or conform to externally imposed gender roles. The spiritual, social, and ceremonial importance they once held was suppressed or erased. Children were forcibly sent to residential schools where their languages, clothing, and identities were systematically stripped from them.

The Cost of Suppression

In the generations following colonisation, the social stigma imposed by Western morality drove many Two Spirit people into lives of isolation or despair. Once seen as gifted, they became targets of derision, misunderstanding, and violence. With few safe spaces to exist as themselves, some were forced to choose between hiding their identity or ending their lives altogether.

Where once Two Spirit individuals were seen as spiritual bridges and keepers of tribal balance, many found themselves unwelcome in both Native and non-Native communities. The resulting alienation continues to affect Indigenous LGBTQ+ individuals today, manifesting in elevated rates of suicide, mental illness, and discrimination.

A Cultural Resurgence

Despite these traumas, the Two Spirit tradition has never fully disappeared. In the past several decades, Indigenous activists, artists, scholars, and community leaders have worked to reclaim and revitalise these suppressed identities. Gatherings such as the International Two Spirit Gathering have helped to educate both Native and non-Native audiences about these traditions, framing them within their original cultural and spiritual contexts rather than through the lens of Western gender frameworks.

In contemporary times, the term “Two Spirit” offers both a unifying identity and a powerful symbol of resistance. It is a reminder of what once was and a call to restore balance. While it is important to note that the term does not translate directly in many tribal languages—and should not be used carelessly outside its cultural context—it nonetheless serves as a vital tool for education and solidarity.

Long before European concepts of gender and sexuality dominated the discourse, Native American cultures lived with a more expansive, spiritually infused understanding of identity. They understood that humanity cannot always be divided cleanly into two categories, and that those who carry both spirits within them are not broken, but whole—vessels of insight, balance, and deep cultural meaning.

As the Lakota once believed, a family with a Two Spirit member was a blessed one. In today’s world, remembering and respecting these beliefs is not just a matter of historical interest—it is a step toward healing, for Indigenous communities and for all of us learning how to live beyond binary thinking.

Sources:

Indian Country Today: “Two Spirit – A Tradition that Cannot Be Erased”

Roscoe, Will. Changing Ones: Third and Fourth Genders in Native North America

Catlin, George. Letters and Notes on the Manners, Customs, and Condition of the North American Indians

Walter L. Williams. The Spirit and the Flesh: Sexual Diversity in American Indian Culture

Comments