Emmett Till: The 14 Yr Old Boy Who Was Abducted, Tortured, And Lynched In Mississippi In 1955

- Anna Avis

- Aug 28, 2025

- 11 min read

Emmett Till was just 14 years old in 1955 when a white woman accused him of wolf-whistling at her in a store in Mississippi. This alleged act would cost the young black boy his life just a few days later when the woman’s husband and his half-brother beat him so severely that he was unrecognisable before shooting him in the head.

The men responsible for the crime had multiple witnesses and mountains of evidence stacked against them, but in an unsurprising decision all too common in the Jim Crow era, an all-white jury cleared them of all charges.

Till’s murder marked not just the loss of a young life, but the start of a story that would galvanise the Civil Rights Movement. Before long, the entire nation would become acquainted with Till's name and witness the horrifying aftermath of the young boy's murder prominently featured on the front pages of newspapers.

Emmett Louis Till was born on July 25, 1941, in Chicago, Illinois. He was the only child of Louis and Mamie Till, although he never knew his father, who perished during World War II. Raised by his single mother, Mamie Till sustained their household by working grueling 12-hour shifts as a clerk for the Air Force.

At the age of five, Till fell ill with polio, ultimately recovering but acquiring a stutter as a consequence.

Described by his mother as a cheerful and considerate youngster, Till once expressed to her, "If you can go out and earn money, I can manage the household." True to his word, he routinely assumed domestic responsibilities, including cooking and cleaning.

Dubbed "Bobo," Till spent his formative years in a middle-class enclave on Chicago's South Side, where he attended school and consistently endeavoured to bring joy to those around him.

"Emmett was a perpetual joker," recalled his former classmate Richard Heard. "He had a treasure trove of jokes he enjoyed sharing. Making people laugh was his forte. Despite his plump physique, while most boys were slender, he didn't let that deter him. He cultivated numerous friendships at McCosh Grammar School, where we were students."

However, the summer of 1955 would mark a profound and transformative turning point in Emmett Till's life.

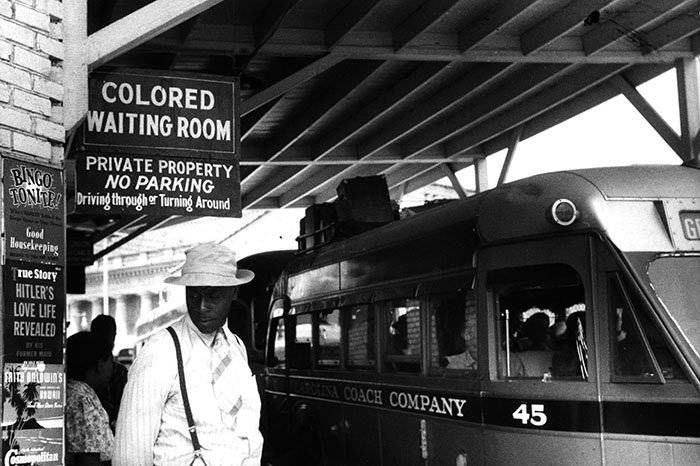

Life In The Jim Crow South

From the late 1800s to the 1960s, Jim Crow laws ruled the South, making racial segregation and discrimination completely legal.

These laws had been in place since the Reconstruction period following the Civil War, but were strengthened around the turn of the century with the Supreme Court’s ruling in Plessy v. Ferguson in 1896. This ruling upheld the constitutionality of racial segregation and made laws establishing “separate but equal” spaces for whites and Blacks.

These regulations barred African-Americans from residing in predominantly white neighborhoods and introduced segregation in various public facilities such as water fountains, restrooms, elevators, cashier counters, and numerous other areas.

Jim Crow laws played a substantial role in prompting many African Americans to migrate northward to escape the constraints of the South. In these urban centres, racial prejudice was still present but comparatively less entrenched.

Emmett Till's family was among those who relocated north, and when he ventured into Mississippi during the summer of 1955, he swiftly realised the dangers that Black people faced in the Jim Crow South.

What Happened To Emmett Till In Mississippi

In August 1955, Emmett Till's great-uncle, Moses Wright, made a trip from Mississippi to Chicago to visit the family. As his visit drew to a close, Wright expressed his intention to take Till's cousin, Wheeler Parker, along on his journey back to Mississippi to visit relatives.

Till fervently implored his mother to allow him to accompany them, and after some persuasion, she consented. It marked her son's inaugural visit to the South, and Mamie took care to emphasise to him that life in the South differed significantly from that in Chicago.

According to Time, she told her son, “to be very careful… to humble himself to the extent of getting down on his knees.”

Merely three days into his journey alongside his uncle and cousin to Money, Mississippi, on August 24, 1955, Till, accompanied by a few friends, entered Bryant's Grocery and Meat Market. The events that transpired within the grocery store remain somewhat unclear. However, it is purported that Till purchased bubble gum and may have engaged in actions such as whistling at, flirting with, or making physical contact with the white female store clerk, Carolyn Bryant, whose spouse, Roy, also possessed ownership of the store.

When Carolyn reported her story to Roy, he flew into a rage.

The Kidnapping And Murder Of Emmett Till

Roy Bryant returned home from a business trip a few days later. After hearing his wife’s account, Roy and his half-brother J.W. Milam drove to Moses Wright’s house in the early hours of August 28, 1955.

They forcibly removed Till from his bed at gunpoint, ignoring Wright’s pleas:

“He’s only 14, he’s from up North,” Wright pleaded to the men according to PBS. “Why not give the boy a whipping, and leave it at that?” His wife offered them money, but they scolded her and told her to return to bed.

Wright led the men through the house to Till when Milam turned to Wright and threatened him, “How old are you, preacher?” Wright responded that he was 64. “If you make any trouble, you’ll never live to be 65.”

The two men tied up Till and put him in the back of a green pickup truck and headed back toward Money, Mississippi. According to eyewitnesses, they transported Till back to Bryant's Groceries and enlisted the assistance of two black men. Their journey eventually led them to a barn in Drew, during which they subjected him to physical assault, including pistol-whipping, which reportedly rendered him unconscious. At that time, 18-year-old Willie Reed observed the passing truck, noting the presence of two white men in the front seat and "two black males" in the rear. While some have speculated that these two black individuals were compelled to participate in the assault on behalf of Milam, they later refuted any involvement in the incident.

Willie Reed said that while walking home, he heard the beating and crying from the barn. He told a neighbour and they both walked back up the road to a water well near the barn, where they were approached by Milam. Milam asked if they heard anything. Reed responded "No". Others passed by the shed and heard yelling. A local neighbour also spotted "Too Tight" (Leroy Collins) at the back of the barn washing blood off the truck and noticed Till's boot. Milam explained he had killed a deer and that the boot belonged to him.

Some have claimed that Till was shot and tossed over the Black Bayou Bridge in Glendora, Mississippi, near the Tallahatchie River. The group drove back to Roy Bryant's home in Money, where they reportedly burned Emmett's clothes.

In an interview with William Bradford Huie that was published in Look magazine in 1956, Bryant and Milam said that they intended to beat Till and throw him off an embankment into the river to frighten him. They told Huie that while they were beating Till, he called them bastards, declared he was as good as they and said that he had sexual encounters with white women. They put Till in the back of their truck, and drove to a cotton gin to take a 70-pound fan, the only time they admitted to being worried, thinking that by this time in early daylight they would be spotted and accused of stealing, and drove for several miles along the river looking for a place to dispose of Till. They shot him by the river and weighted his body with the fan.

Mose Wright remained stationed on his front porch for a span of twenty minutes, anxiously awaiting Till's return, refraining from returning to his own bed. Eventually, accompanied by another individual, he journeyed into Money, procured gasoline, and embarked on a quest to locate Till. However, their efforts proved unsuccessful, leading them to return home by 8:00 am.

Upon learning from Wright that he was reluctant to involve the police due to apprehensions for his safety, Curtis Jones placed a call to the Leflore County sheriff. He also reached out to his mother in Chicago, who, overwhelmed with distress, contacted Emmett's mother, Mamie Till-Bradley. Subsequently, Wright and his wife, Elizabeth, drove to Sumner, where Elizabeth's brother established contact with the sheriff.

Tragically, three days later, Till's lifeless body was recovered from the Tallahatchie River. The extent of the brutality inflicted upon him was so severe that Wright could solely identify him by a ring that his mother had given him before the trip.

Upon her request, Mamie Till arranged for her son's remains to be transported back to Chicago. Upon viewing her son's disfigured body, Mamie resolved to hold an open-casket funeral, allowing the entire world to witness the horrific fate that had befallen her child.

Additionally, Mamie extended an invitation to Jet, an African-American magazine, to attend the funeral and document photographs of Till's unrecognisable body. Subsequently, these gruesome images were published, drawing nationwide attention to the horrifying incident.

The Arrest And Trial Of Roy Bryant And J.W. Milam

Not even two weeks after his body was buried, Roy Bryant and J.W. Milam were on trial for the murder of Emmett Till. There were several witnesses to the killers’ actions that night, and they were thus the obvious suspects for Till’s murder and quickly apprehended.

When the trial began in September 1955, the national and international press came to Sumner, Mississippi to cover the events. Moses Wright, Willie Reed, and others sacrificed their safety and lives to testify against the two white men in court, saying that the men were indeed Till’s killers.

Meanwhile, Carolyn Bryant delivered an impassioned testimony, alleging that Till had verbally threatened her and physically accosted her. This testimony proved decisive to the all-white jury, which wasted scarcely an hour before acquitting Till's assailants. Bryant and Milam were cleared of all charges, including kidnapping and murder.

One juror remarked that it would have taken even less time had they not stopped to drink a soda.

However, less than one year later, in January 1956, Bryant and Milam would confess to murdering Till in a Look magazine article titled, “The shocking story of approved killing in Mississippi.” The men got $4,000 for selling their story.

In the article, the pair gleefully admitted to murdering the 14-year-old boy and expressed no remorse for their heinous deed. They said that when they kidnapped Till, they only intended to beat him up, but decided to kill him when the teen refused to grovel. Milam explained his decision to Look saying:

“Well, what else could we do? He was hopeless. I’m no bully; I never hurt a n***** in my life. I like n*****s – in their place – I know how to work ’em. But I just decided it was time a few people got put on notice. As long as I live and can do anything about it, n*****s are gonna stay in their place… I stood there in that shed and listened to the n***** throw that poison at me, and I just made up my mind. ‘Chicago boy,’ I said. ‘I’m tired of ’em sending your kind down here to stir up trouble. Goddam you, I’m going to make an example of you – just so everybody can know how me and my folks stand.”

Because the men had already been tried and acquitted of Till’s murder, their callous confession garnered no punishment.

The Impact Of Emmett Till’s Murder On The Civil Rights Movement

Mamie Till’s decision to display her son’s body in an open casket allowed the world to see just the sort of brutality that African-Americans could face, and consequently galvanised the Civil Rights Movement.

Once the nation saw those haunting images published in Jet magazine, they couldn’t ignore the brutality any longer.

Merely a few months following Emmett Till's tragic demise, Rosa Parks took a stand by refusing to yield her bus seat, catalysing the Montgomery Bus Boycott, a moment many consider as the true commencement of the Civil Rights Movement. Reverend Jesse Jackson conveyed to Vanity Fair that Parks had shared with him that Till played a significant role in her determination not to surrender her seat.

“I asked Miss Rosa Parks [in 1988] why she didn’t go to the back of the bus, given the threat that she could be hurt, pushed off the bus, and run over because three other ladies did get up,” Jackson said. “She said she thought about going to the back of the bus. But then she thought about Emmett Till, and she couldn’t do it.”

The Los Angeles Times put it in perspective, saying, “If Rosa Parks showed the potential of defiance, [some historians] say, Emmett Till’s death warned of a bleak future without it.”

As Robin D. G. Kelly, chair of the History department at New York University told PBS:

“Emmett Till, in some ways, gave ordinary black people in a place like Montgomery, not just courage, but I think instilled them with a sense of anger, and that anger at white supremacy, and not just white supremacy, but the decision of the court to exonerate these men from murdering – for outright lynching this young kid – that level of anger, I think led a lot of people to commit themselves to the movement.”

Indeed, to many, the story of Emmett Till represents a turning point. Scholar Clenora Hudson-Weems calls Till the “sacrificial lamb” of civil rights and Amzie Moore, an NAACP operative, believes that Till’s brutal killing was the start of the Civil Rights Movement altogether.

Till might not have been around to see the Civil Rights Movement make the kind of changes that would have spared his life, but his death was instrumental in getting the movement off the ground in the first place.

The Enduring Legacy Of Emmett Till’s Story

Even decades after his murder, the story of Emmett Till’s death continues to make headlines.

In perhaps the most significant recent revelation, Carolyn Bryant admitted in 2007 to Timothy Tyson, a Duke University senior research scholar, that she fabricated the majority of her testimony at trial.

One of the most damning things that she said during Emmett Till’s murder trial was that he made verbal and physical advances on her, but as she later told Tyson, “That part’s not true.”

At the time of her interview, Carolyn Bryant was in her 70s and seemed to feel some remorse for her part in the brutal murder, unlike her ex-husband, Roy. She told Tyson, “Nothing that boy did could ever justify what happened to him.”

Astoundingly, in 2018, the Justice Department initiated a reinvestigation into the Till case, citing the discovery of "new information" as the catalyst. This development rekindled hope that justice might ultimately be served for those responsible for the 14-year-old's death over six decades earlier.

Not only is the narrative of Emmett Till returning to the forefront, but his memory is as well. In July 2018, a commemorative marker for Till near the Tallahatchie River was subjected to its third instance of desecration since its installation. Initially, the sign was stolen and never recovered. Subsequently, upon replacement, it was vandalised, this time with numerous bullet holes. Even following another replacement, the marker endured repeated acts of vandalism.

Patrick Weems, a co-founder of the Emmett Till Interpretive Center, told CNN that the attacks are fueled by hatred.

“Whether it was racially motivated or just pure ignorance, it’s still unacceptable,” Weems said. “It’s a stark reminder that racism still exists.”

Sources

PBS – The Murder of Emmett Till https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/emmett-till-story

The New York Times – Emmett Till (coverage and archival material) https://www.nytimes.com/topic/person/emmett-till

The Washington Post – How Emmett Till’s murder changed America https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/retropolis/wp/2017/08/28/the-murder-of-emmett-till-which-changed-america/

Smithsonian Magazine – Emmett Till: 60 Years Laterhttps://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/what-emmett-till-means-to-america-60-years-later-180956762/

FBI Vault – Emmett Till Investigation https://vault.fbi.gov/Emmett%20Till

Look Magazine (1956) – “The Shocking Story of Approved Killing in Mississippi” by William Bradford Huie (Bryant & Milam’s paid confession; reprinted in archives)[Archived summary here] https://archive.nytimes.com/www.nytimes.com/books/97/12/28/home/till-confession.html

Time – Remembering Emmett Till https://time.com/4319935/emmett-till-legacy/

The Los Angeles Times – Emmett Till’s legacy and the Civil Rights Movement https://www.latimes.com/nation/la-na-emmett-till-legacy-20170827-story.html

CNN – Emmett Till Memorial Sign Vandalismhttps://edition.cnn.com/2019/07/27/us/emmett-till-sign-replaced-trnd/index.html

Tyson, Timothy B. (2017). The Blood of Emmett Till. New York: Simon & Schuster.(Modern historical analysis; includes Carolyn Bryant’s later admission.)

Comments